There’s no denying that 2020 was an unprecedented year, so I’m doing something unprecedented: combining film and TV into one year-end list.

Steve Carrell sucking up oxygen in Space Force.

Worst TV: Space Force

Satirizing Donald Trump’s useless new branch of the military probably seemed like a good idea at the time. But Space Force is an aggressively unfunny boondoggle that normalizes the neo-fascism that almost swallowed America in 2020.

John David Washington (center) and Robert Pattinson (right) are impeccably dressed secret time agents in Tenet.

Worst Picture: Tenet

Christopher Nolan’s latest gizmo flick was supposed to save theaters from the pandemic. Instead, it was an incoherent, boring, self-important mess. You’d think $200 million would buy a sound mix with discernible dialogue. I get angry every time I think about this movie.

We Can’t Wait

Best Memphis Film: We Can’t Wait

Lauren Ready’s Indie Memphis winner is a fly-on-the-wall view of Tami Sawyer’s 2019 mayoral campaign. Unflinching and honest, it’s an instant Bluff City classic.

Grogu, aka The Child, aka Baby Yoda

Best Performance by a Nonhuman: Grogu, The Mandalorian

In this hotly contested category, Baby Yoda barely squeaks out a win over Buck from Call of the Wild. Season 2 of the Star Wars series transforms The Child by calling his presumed innocence into question, transforming the story into a battle for his soul.

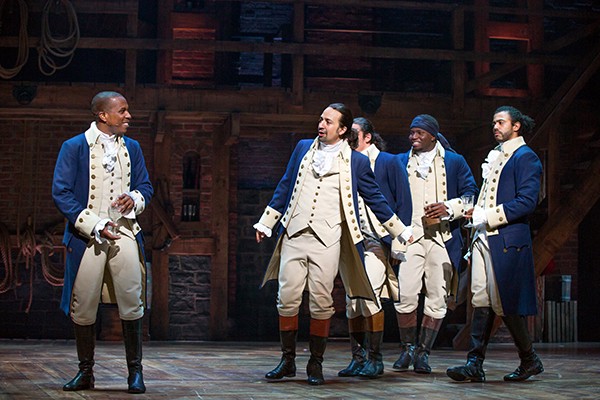

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton

Most Inspiring: Hamilton

The year’s emotional turning point was the Independence Day Disney+ debut of the Broadway mega-hit. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop retelling of America’s founding drama called forth the better angels of our nature.

Film About a Father Who

Best Documentary: Film About a Father Who

More than 35 years in the making, Lynne Sachs’ portrait of her mercurial father, legendary Memphis bon vivant Ira Sachs Sr., is as raw and confessional as its subject is inscrutable. Rarely has a filmmaker opened such a deep vein and let the truth bleed out.

Cristin Milioti in Palm Springs

Best Comedy: Palm Springs

Andy Samberg is stuck in a time loop he doesn’t want to break until he accidentally pulls Cristin Milioti in with him. It’s the best twist yet on the classic Groundhog Day formula, in no small part because of Milioti’s breakthrough performance. It perfectly captured the languid sameness of the COVID summer.

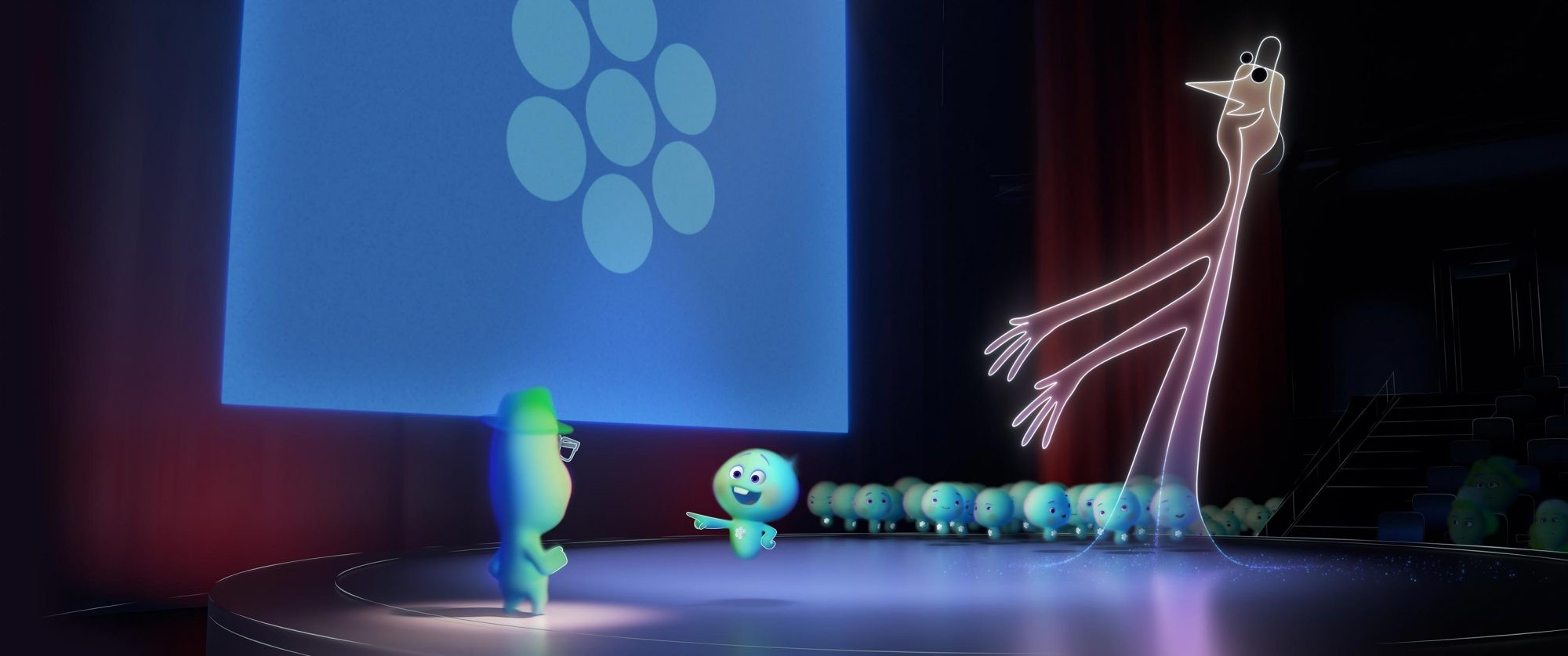

Soul

Best Animation: Soul

Pixar’s Pete Docter, co-directing with One Night in Miami writer Kemp Powers, creates another little slice of perfection. Shot through with a love of jazz, this lusciously animated take on A Matter of Life and Death stars Jamie Foxx as a middle school music teacher who gets his long-awaited big break, only to die on his way to the gig. Tina Fey is the disembodied soul who helps him appreciate that no life devoted to art is wasted.

Jessie Buckley

Best Performance: Jessie Buckley, I’m Thinking of Ending Things

Buckley is the acting discovery of the year. She’s perfect in Fargo as Nurse Mayflower, who hides her homicidal mania under a layer of Midwestern nice. But her performance in Charlie Kaufman’s mind-bending psychological horror is a next-level achievement. She conveys Lucy’s (or maybe it’s Louisa, or possibly Lucia) fluid identity with subtle changes of postures and flashes of her crooked smile.

Isiah Whitlock Jr., Norm Lewis, Delroy Lindo, Clarke Peters, and Jonathan Majors in Da 5 Bloods.

MVP: Spike Lee

Lee dropped not one but two masterpieces this year. Treasure of the Sierra Madre in the jungle, the kaleidoscopic Vietnam War drama Da 5 Bloods reckons with the legacy of American imperialism with an all-time great performance by Delroy Lindo as a Black veteran undone by trauma, greed, and envy. American Utopia is the polar opposite; a joyful concert film made in collaboration with David Byrne that rocks the body while pointing the way to a better future. In 2020, Lee made a convincing case that he is the greatest living American filmmaker.

Rhea Seehorn and Bob Odenkirk in Better Call Saul

Best TV: Better Call Saul

How could Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould’s prequel to the epochal Breaking Bad keep getting better in its fifth season? The writing is as sharp as ever, and Bob Odenkirk’s descent from the goofy screwup Jimmy McGill to amoral drug cartel lawyer Saul Goodman is every bit the equal of Bryan Cranston’s transformation from Walter White to Heisenberg. This was the season that Rhea Seehorn came into her own as Kim Wexler. Saul’s superlawyer wife revealed herself as his equal in cunning. If she can figure out what she wants in life, she will be the most dangerous character in a story filled with drug lords, assassins, and predatory bankers.

Michael Stuhlbarg and Elisabeth Moss in Shirley.

Best Picture: Shirley

Elisabeth Moss is brilliant as writer Shirley Jackson in Josephine Decker’s experimental biographical drama. Michael Stuhlbarg co-stars as her lit professor husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, who is at once her biggest fan and bitterest enemy. Into this toxic stew of a relationship is dropped Rose (Odessa Young), the pregnant young wife of Hyman’s colleague Fred (Logan Lerman), who becomes Shirley’s muse/punching bag. If Soul is about art’s life-giving power, Shirley is about art’s destructive dark side. Shirley is too flinty and idiosyncratic to get mainstream recognition, but it’s a stunning, unique vision straight from the American underground.