Valerie June played the Tonight Show last night. She starts after the last hash mark in the video timeline. 37:42. You can see it if you watch a million commercials. Seriously, a million. You will watch 2 minutes 30 seconds of commercials; Xfinity seconds, not real seconds. It’s worth the wait. Compared to her David Letterman appearance, she seems more at home with her band and more comfortable in her role. She seems to be justifying all the recent publicity. All the best from Memphis.

Tag: show

Wild Abandon

You’ll find no provincialism, colloquial kitsch, or partisan bickering in the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art’s current exhibition, “Perspectives.” From its explosive beginning to its magnetic end, this regional art show, put together by globe-trotting juror/curator Michael Rooks, brainstorms possibilities.

Memphian Bo Rodda plops us right into the heart of -46m, 248m, -572, a computer-generated universe where thousands of viewpoints simultaneously explode toward and away from the viewer. There is no horizon line, no ground, no bumper-to-bumper traffic in this parallel world. Instead, swerving lines, printed on metallic paper in endless shades of gray, read like stainless-steel intergalactic freeways that have swallowed up every square inch of space.

Nashville artist Kit Reuther’s oils on canvas are as open-ended. In two of her strongest works, Blueline and Porcelancia, weeds scattered across crystalline cold landscapes become tours de force of painting and imagination. Dried pods morph into small urns, faded blue china, and hieroglyphs that wash into streams of ink excreted by squids and seaweeds floating in deep waters.

Memphian Jon Lee’s mixed-media paintings appear to reach a boiling point. Exotic animals materialize out of scraped and scumbled backgrounds, and venom drips from the mouth of a cobra. Acrylics and aerosols crash across his surfaces and drip over the edges of these 21st-century abstractions mixed with the raw energy and materials of graffiti.

Many of the works in “Perspectives” lie at the edge of art and consciousness. Memphian Terri Jones’ Stone’s Line is quirky, nostalgic, and so minimal you could miss it altogether. It’s worth finding for the associations it evokes, including the root-beer float you shared on your first date decades ago. Fifty-year-old paper straws thread together and disappear into the ceiling. As you move around Jones’ free-hanging strand of straws and memory, notice how it sways, creating shadows that ooze like colas onto gray carpet.

Patrick DeGuira’s Cannibal’s Makeover (detail)

Local artist Phillip Lewis’ installation, “Atmosphere,” both grounds us and arcs our point of view straight up. Droning sounds come from a speaker on the ceiling above a translucent blue rectangle that pulsates like an idle video monitor. Look up into Lewis’ ingenious mandala and acclimate to its sound. Your heart rate will slow to the beat of the visual pulse, and you’ll find yourself drawn some 300 yards above the museum where Lewis recorded winds with a parabolic mike.

Passionate, open-ended dialogue reaches a high point with Memphian Cedar Nordbye’s wall-filling installation that builds, explores, and destroys civilization. Two-by-fours inscribed with mind-bending mottoes climb up and over the top of a 10-foot partition. A cast of characters, including Billie Holiday, Abbie Hoffman, Franz Kafka, and Noam Chomsky, is exquisitely rendered in ink and acrylic on the surfaces of wooden beams that build both architecture and ideas. On the far right, 2×4’s tumble past cartoons of jet planes, replicas of the Empire State Building, and an image of a monk setting himself on fire.

A wry, informed mind is indispensable for deciphering Nashville artist Patrick DeGuira’s Cannibal’s Makeover, a small sooty room where shards of glass and human femurs are piled on the floor, hatchets are embedded in walls, human skulls are candleholders, a well-dressed man levitates just beyond reach, and almost everything (chairs, mirrors, bones, walls) is painted a dark gray. Humans feeding off humans will always be with us, DeGuira’s dark, deadpan installation seems to say. But ritual sacrifice is so passé. Imagine, instead, dark forces as heads of countries and corporations chew us up and spit us out, millions of us. Instead of devouring humans, one by one, in this high-tech world think global warfare, corporate takeover, and environmental devastation.

Memphis artist Niles Wallace works another kind of magic. He transforms hundreds of layers of shag carpet into two of the most moving works in the show. His cone-shaped Temple suggests many kinds of worship, including stupas, sweat lodges, and pyramids. Suspended a foot or so from the ground, his circular Portal suggests the hoops through which we must jump to reach subtler realms. You’ll find no ascetic, static perfection in Wallace’s heavenly visions. Instead, we get a comforting spirituality inflected with the frayed, shaggy, well-worn textures of life.

Murfreesboro artist Jacqueline Meeks explores our darker impulses with a series of ink drawings of a bejeweled, plumed aristocrat. Meeks’ metaphor for self-indulgence spinning out of control is political/social/psychological satire at its best. With her head covered by intricate petticoats and her elephantine bottom bared, an 18th-century French courtesan somersaults across the left wall of the gallery.

Above the entrance to “Perspectives,” William Rowe’s neon sign shouts “forget me” in ironic, electric-blue writing. Forget you? Forget this show which so beautifully reflects this mesmerizingly complex world? Not likely.

“Perspectives” at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art through September 9th

Cosmonauts

Located somewhere between mortals and the gods, George Hunt’s portraits of Southern soul at D’Edge Art include misguided devils, fieldhands who play the music of the spheres, and bruised Madonnas.

In Hunt’s complex cosmology, Satan is a creature more heart-broken and impish than evil. In Red Devil Blues, Satan wears his heart on his sleeve. His right eye is dilated and huge. Primal energy coils like a snake from his lower torso and sways to the tunes this horned, baby-faced devil plays on his purple ukulele.

Many of Hunt’s vivid, textured canvases combine wry humor with knowing nods to the masters. El-Roitan, The Man shows a grimacing, barefooted fieldhand whose neck and torso are an antique cigarette label seamlessly collaged onto the canvas. El-Roitan plays the music of his soul on a Greek lute surrounded by a Miro-like universe of dancing planets, insects, flowers, and stars.

The women of Hunt’s work are as full of mojo, art history, and blues as the men. In Sister Madam Walker, an almond-shaped face combines the features of an African mask with those of a medieval Madonna. A sliver of pale moonlight cups her cheek. White cotton fabric collaged into a Sunday-best dress frames a face on which Hunt maps out life’s passions and dark passages with a stunning mosaic of purples, mahoganies, and midnight blues.

At D’Edge Art through July 31th

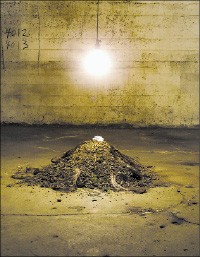

In her installation, “Jewels,” at Medicine Factory, Erinn Cox elicits intense visceral reactions and develops surprisingly rich metaphors with nine piles of dirt topped with small pieces of plaster painted with high-gloss enamel. Some of the plaster pieces are shaped like calcified kidneys or hearts. On other piles, the opalescent material clusters like pearls, suggesting that

from ‘Jewels’ by Erinn Cox

life’s irritants bring experience (“pearls of wisdom”) as well as disease.

There are no hierarchies, no special powers or privileges here. Thick strands of human hair twist like earthworms aerating the soil. Hanging from the ceiling above each mound of dirt is a naked light bulb like one sees in a room used for interrogations or as a growth light. Both images fit. On June 7, 2004, Erinn Cox almost died. Since that time, she has explored her feelings regarding death and disease through memento mori that ask tough questions. Cox looks into nine piles of death/decay (a number connoting the end of a cycle) and finds optimal conditions for another round of life.

At Medicine Factory through June 29th

In Lauren Kalman’s exhibition, “Dress Up Dress Down,” also showing at Medicine Factory, a svelte figure floats in pure white light on a tiny LCD screen that dangles outside its casing, its circuitry exposed. At first glance, we wonder if Kalman has jerry-rigged us into some celestial realm. Up close, we realize the angel is the artist dressed in a white suit and swinging on a rope in an overexposed video titled Drop. We never see Kalman let go, but judging from the strain in her arms and the grimace on her face, her fall is imminent. Hanging by the Teeth finds the artist, dressed in the same silken suit, hanging by her teeth from another rope.

Rows of medicine bottles, frog skeletons, jaw bones, and jars used to hold biological specimens line up against Medicine Factory’s walls. Far back in the gallery, Kalman imagines her own demise on a corroded mortuary table she welded to the dimensions of her body.

Look, really look, this artist seems to be saying, at the ideologies that drive you to excel, to climb some corporate or spiritual ladder. Death is inevitable. When you strive for perfection in a body subject to aging and disease and push yourself to the limits of endurance, you hasten your decline.

In another video, Kalman dramatically underscores her ideas by wrapping a skull around her genitalia with a long swatch of fabric. Rather than an affront, her measured movements, repeated again and again in a video loop projected onto one of Medicine Factory’s scarred walls, become a meditation on Eros/Thanatos.

At Medicine Factory through June 29th

Off the Wall

Where to start with an exhibition as powerful as “Veda Reed: Daybreak/Nightfall” at David Lusk Gallery? I could tell you how Reed’s complex glazes and subtle gradations of color in her large oils on canvas create optical illusions that dance like the Northern Lights across the gallery walls. I could describe how weird, beautiful, and surreal her skyscapes become as she mixes day with night, memory with vision, and what looks like the cosmos with the volatile and wide-open Oklahoma skies of her childhood.

I could tell you how in Daybreak: The edge of dawn, 2 a huge planet dwarfs a sun that splits into two and spews cadmium yellow, then crimson, then mahogany, then burgundy into the darkness, or how some of Reed’s suns and planets break into shards of light that are satisfying patterns of abstraction, or how soft billows of gray vermillion in an elongated sky in Nightfall: “Earth’s joys grow dim; its glories pass away” ease us into an eternity envisioned, in part, by Henry F. Lyte’s hymn, “Abide with Me.”

Or we could go straight to the disturbingly beautiful Nightfall: “fast falls the eventide …”, where a black dome arches over a neon saucer of light hovering between a vermillion sky and seamless black sea. Beginnings and endings simultaneously play out as we glimpse first light through the mouth of Plato’s cave and peer at the last rays of the sun over the lip of a vault whose domed lid is closing.

With endless aureoles of yellow and vermillion fading into smoky crimson and black, Reed reaches higher and deeper into the cosmos than she ever has before.

At David Lusk Gallery through April 28th

As demonstrated in “Annabelle Meacham: Recent Work” at Jay Etkin Gallery, Meacham can do just about anything with paint and canvas. In her rendition of art deco’s sheer beauty, Hope and Desire, a pink lily is set against porcelain skin on a jewel-toned background in which every millimeter is gilded and faceted. In The Portrait, a matron with a stern expression sits with her white Persian cat in a fishbowl existence wryly emphasized by the goldfish swimming Magritte-like around her head.

What makes this body of work most powerful is not the surreal surprise or hyper-real detail but Meacham’s poignant and astute observations about the natural world. In Revelations, a woman sits at a grand piano that has sprouted a lush garden. She and her small hound look at the full moon through the large windows of the sanctuary/prison of their beautifully appointed drawing room.

In the whimsical Reflections, tiny deer painted on a Qing dynasty vase leap across precipices of mountains that jut straight up from flat land. White flowers pattern the chartreuse vase to the right. At center a butterfly flies past another finely sculpted vessel: a bare human derriere. Tendrils sprout from it in an image at the edge of propriety that weaves fertile bodies, the fertile earth, and fertile imaginations into one organic whole.

At Jay Etkin Gallery through April 21st

During the past year, Dwayne Butcher married, traveled widely, and began graduate studies at Memphis College of Art — all of which is reflected in Butcher’s exhibition “Art Made with a Ring” at Delta Axis @ Marshall Arts.

In each of the 16 panels of Multi-Scully #1, a drip of enamel flows down, thrusts up, or oozes across art that is, in all other regards, stark and geometric. Placed side-by-side, the panels become kaleidoscopic metaphors for life undergoing change.

Several of the show’s strongest paintings reference Marfa, a Texas town whose landscape is as stark as any abstract artwork. Marfa is also the permanent site for the work of minimalist Donald Judd, one of Butcher’s major influences. The soft earth tones, round edges, pale mauve drips, and blue background of Blue Door at Marfa #3 evoke Marfa’s adobes, buttes, mesas, and clear-blue skies.

This painting is a welcome addition to Butcher’s art. Last year’s exhibition, “Supermandamnfool,” was sharp-edged and saturate. Add to that body of work Butcher’s Blue Door at Marfa series, and you get an artist whose expanding vision is rethinking minimalism.

At Delta Axis @ Marshall Arts through April 28th

Designer Genes?

Have you ever been walking down the street and said to yourself, “Man, I wish there was somewhere I could go to hear the piano stylings of a certifiable master, learn about flowers, stained glass, and mid-century interiors, eat like a sultan, pick up some tips on hanging pictures, get my scrapbooking skills up to par, and generally hip myself to the latest and greatest elements of contemporary art and design”? If so, all of that and much more is on tap at the Brooks Museum League’s Art and Design Fair, which runs from Friday, March 30th, to Sunday, April 1st, at the Agricenter.

Retro-fans will want to visit on Friday at 2 p.m. when Philadelphia

Inquirer design columnist Karla Albertson delivers a lecture on decorative arts from the 1940s to 1960s. Albertson’s more than a design maven. She’s a trained archaeologist who can get your space-age bachelor pad (or modern love nest) looking just the way Charles Eames would have wanted it.

An opening-night party on Thursday, March 29th, from 5:30 to 8 p.m., features a silent auction, cocktails, hors d’oeuvres, and entertainment by Panamanian pianist Alex Ortega. Tickets for the preview party are $30.

The Brooks Museum League’s Art and Design Fair, Friday-Sunday, March 30th-

April 1st, Agricenter International, $10. For additional information, call 861-3637

or visit brooksmuseum.org.

River Rat

It sounds like a punk-rock version of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn — a group of twentysomething hippies build homemade boats using parts from the trash and set out from Minneapolis for a summer-long trip down the Mississippi River.

Every year, a mix of artists, poets, activists, anarchists, and adventure-seekers craft boats using salvaged materials, like old wood and Styrofoam. Most live up north and spend July through the fall exploring various river towns along the Mississippi.

“They show up in towns like migratory birds on their way down south for the winter,” says local artist Andrea Buggey.

Back in 2005, Buggey decided to join the ramshackle crew. She headed to Minneapolis, got some help building a boat she affectionately dubbed the Ida B, and set sail on July 4th. Photographs, drawings, and poetry from her trip are on display in “Traveling Down the River” at Java Cabana through March 31st.

Originally, Buggey hopped aboard a boat for only a day, packing her bike so she could ride home when she got back on dry land. She had such a great time, however, she decided to spend the following summer traveling with the crew.

Two of the river regulars helped Buggey construct her boat, an open-air pontoon-style craft made from cypress wood, Styrofoam, and plastic bottles for buoyancy.

“Using salvaged materials is a lifestyle thing — saving what other people have wasted,” says Buggey. “It’s like recycling.”

For example, white PVC piping curved into arches over the top of the Ida B resemble an elephant ribcage. When it rained, Buggey would drape a blue tarp over the piping to keep dry.

“All the boats had motors, but the Ida B also had a paddle wheel. It was made of cypress planks and was hooked up to two exercise bikes, which propelled it pretty quickly. You just had to ride the bike,” says Buggey.

Altogether, there were 12 crew members occupying five homemade boats: the Ida B, Shadow Builder, Gator Bait II, Bobby Bobula, and the Leona Joyce. Throughout the months-long journey, the crew would hop from boat to boat to visit, dine, and help captain. Occasionally, adventurous folks from towns along the way would join them and ride for days or even weeks before getting off.

“Four of the boats had dinghies that we’d trail behind us,” says Buggey. “We’d keep our bicycles on the dinghies so when we got to towns, we could travel to get more supplies like food and gas.”

Meals, cooked on camp stoves on boats or campfires on beaches, were generally communal. Boats were hooked together for eating and sleeping, so only one person had to captain rather than five. Most meals involved fish or food from cans, seasoned with fresh herbs grown on Buggey’s boat garden.

At night, a couple of people usually stayed awake to steer and serve as lookout for barges or other river traffic. But occasionally, even the lookouts would fall asleep on the watch.

“One night when we were floating together, we woke up and discovered we’d landed in a stump field,” says Buggey. “It was very shallow and we all had to get out and push. The propellers on the motors were tangled with weeds.”

Sometimes the crew would retire their sails for several days, opting to hang out in towns.

“There was this small town in Illinois where all the people were very frightened of us. They were whispering to each other and following us around in stores. We created this panic,” says Buggey.

The crew brushed the experience off until they befriended some teenagers a few towns down the river. The teens claimed the previous town was under the “Curse of the River Gypsy King.”

“They told us that during the Depression, there was this group of gypsies that lived on houseboats,” says Buggey. “They stopped in the town and their leader, the gypsy king, had a heart attack. They took him to the local hospital, but he was refused service. He died in the waiting room, so the gypsies cursed the town. The tale has apparently carried on.”

By the time the boats reached Missouri in October, Buggey was running low on money for gas. Prices were high after Hurricane Katrina, so she decided to abandon ship and call her parents to pick her up. She left her boat in a creek while the rest of the crew headed on to New Orleans.

Buggey says the travelers generally give the boats away or sell them for a couple bucks since they often can’t afford to trailer them back north. New boats are constructed for the next year’s trip. Buggey doubts she’ll be building another boat though:

“I might go visit when they pass through, but I wouldn’t want to do a whole season of traveling again. I did gain a deep respect for the river and nature. There’s so much beauty and wilderness out there. And we pretended like we were pirates.”

“Traveling Down the River,” photos, drawings, and poetry byAndrea Buggey, are on display at Java Cabana (2170 Young) through March 31st.

Breathe In

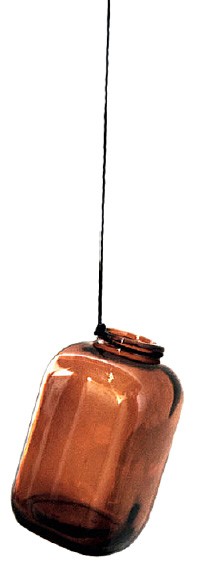

“Inhale … From the Corners,” Terri Jones’ exhibition at David Lusk Gallery, consists of three corroded sheets of metal, three sheets of vellum, two bottles, a black string, a piece of paraffin, a glass marble, and two long strips of gray felt. The show is so spare some viewers may wonder if the work has already come down. Those who stay long enough to explore Jones’ delicate lines, remarkable economy of gesture, and translucent materials will find themselves immersed in a nearly seamless symphony of light and space.

This symphony’s allegro movement occurs early in the morning when sunlight pours through plate-glass windows and bathes two large sheets of vellum titled Inhale. Hanging from the gallery’s 20-foot-ceiling and swaying with the slightest breeze, Inhale‘s large expanses of glowing, undulating vellum (a material used for sacred texts and ancient manuscripts) produce a quality of light bordering on the sublime.

Jones attunes our senses to the subtlest of stimuli. Tiny, nearly invisible ovals fount up and flow down Inhale‘s surfaces two at a time, then single file, farther and farther apart, until they disappear like drops of water in a translucent, silky-smooth vellum sea.

A black string draped over steel rods protruding from the far back wall teems with metaphor and perceptual play. Two identical golden bottles are hidden behind the reception desk close to the floor. They hang from the ends of the string, pulling it taut and creating the outline of a three-sided square. The title of the work, Fair, and the hidden gold (the only touch of color in the show) suggest layered meaning and special significance.

While many of Jones’ titles, such as Reach, Trace, Inhale, and Pause, are verbs that indicate subtle, incremental movement, Fair is a descriptor loaded with aesthetic and ethical evaluation regarding beauty, equity, and common decency. What holds the string structure in place, Jones seems to be saying, is the same delicate balance and careful handling that hold together any artistic composition, psyche, relationship, or community.

Part of Terri Jones’ exhibit ‘Inhale…From the Corners’ at David Lusk Gallery

From its starting point at the center of the gallery, Course, a long, narrow carpet of gray felt, crosses the floor diagonally and dead-ends beneath three sheets of metal titled Gift. Instead of forming the sides of one of Robert Morris’ inert gray cubes or standing alone, powerful and iconic, like one of Richard Serra’s steel slabs, three small, corroded metal squares are hinged like the panels of an altarpiece whose images and written doctrines vanished long ago. Corrosion has dissolved colors, words, shapes, even the gouges and scratches, transforming Gift into something veiled and haunting.

A slender eraser placed between two panels brings to mind the crayon drawing that Willem de Kooning allowed Robert Rauschenberg to obliterate: Forty erasers and one month’s labor later, Rauschenberg reduced the drawing to a nearly blank sheet of paper.

Instead of erasing a work of art, Jones reduces David Lusk Gallery to a nearly blank canvas, a tabula rasa full of residual energy that begs to be shaped and reshaped. Two graphite lines titled Reach and Pause drawn directly on the left and back gallery walls are punctuated, respectively, with a fresh slab of paraffin and a cast glass ball. The marble-sized ball looks poised for action, ready to complete its roll down the wall and across the floor.

The 19-foot-long portal titled Trace, delicately drawn on vellum and nailed to the right wall just above the floor, allows us, like Alice, to go through the looking glass down the rabbit hole into an open, luminous vision of reality where we not only think about but experience Milan Kundera’s “unbearable lightness of being,” Buddhism’s Sky Mind, and T.S. Eliot’s transpersonal vision described in the final segment of Four Quartets:

“When the last of earth left to discover/Is that which was the beginning;/ … Not known, because not looked for/But heard, half-heard, in the stillness/Between two waves of the sea./Quick now, here, now, always –/A condition of complete simplicity/(Costing not less than everything).” Through March 31st