The 1968 murder in Memphis of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a man whom legions of people the world over regard not only as a monumental historical figure and champion of human rights but as something of a secular saint, seems to cast a larger shadow over humankind year by year.

This is especially the case when, almost half a century after the foul deed, suspicions continue that the late convicted assassin, James Earl Ray, was not a lone gunman but either an innocent patsy or a cog in a still unraveled conspiracy involving (pick one) the FBI, the Mafia, the Ku Klux Klan, or even unnamed black radicals angered at the relatively moderate positions of Dr. King.

This very week, as a continuation of the solemn observances that took place on Saturday, April 4th, at the assassination site — formerly the Lorraine Motel and, since 1991, the National Civil Rights Museum — the latest conspiracy-minded author, one John Avery Emison, will appear at the Museum to discuss his new book, The Martin Luther King Congressional Cover-Up: The Railroading of James Earl Ray.

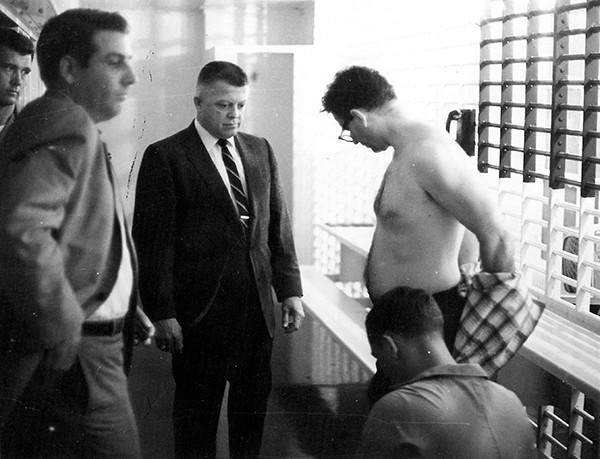

There is a famous photograph, featured on the cover of this issue, of the moment in July 1968 when a trussed-up Ray, who had been apprehended in London and extradited to Memphis via an intercontinental air flight, arrived at the Shelby County jail in the company of then Sheriff William N. Morris.

It was a signature moment in American history, and certainly one for Morris, whose receipt and subsequent incarceration of King’s accused killer constituted one of the highlights of a Zelig-like career in which the Mississippi sharecropper’s son rose from insignificance and bleak poverty to hold the offices of sheriff and Shelby County mayor, effecting major governmental and social change in a time of political transition and hobnobbing with presidents and other heads of state.

Now 83, Morris has numerous credits to his name (see box, p. 23), but surely one of his signal achievements, one of which he is proudest today, was his handling of the pre-trial incarceration of the accused assassin.

In the aforementioned picture, Morris, then 35 and serving in the second of his three two-year terms as sheriff, stands behind Ray with a firm hold on the bound arms of his captive, while Ray, head bowed and eyes cast down, is the very image of crestfallen surrender. That picture reassured a stricken world that justice might be done.

In reality, as Morris recalls, the demeanor of Ray, a career criminal with a deserved reputation as an escape artist, was more sullen than abject. As the picture was snapped, he had just uttered an epithet — “Sonofabitch!” — and launched a flurry of wild kicks at Morris and Gil Michael, the local photographer who had been engaged by the sheriff to document the occasion.

Eventually, Ray was ushered into his cell and became aware of just how secure his incarceration was to be — the result of extraordinary precautions on Morris’ part.

Above all, the sheriff was determined that Ray would not meet the fate of Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, who was famously gunned down within two days of his capture by the shadowy night-club owner Jack Ruby while being transported by Dallas police.

To get a sense of just how such a lapse in security could have occurred, Morris had been to Dallas and logged time with authorities there. He had also been to Los Angeles consulting with Sheriff Peter Pitchess of that jurisdiction during the trial of Sirhan Sirhan, who was eventually convicted of murdering JFK’s brother, Senator Robert Kennedy.

That second Kennedy assassination had occurred a few short weeks after the MLK assassination in Memphis, but because of the two-and-a-half months’ lag-time in capturing Ray, who had traversed America and flown to Europe on a false passport after the King assassination, Sirhan’s trial had taken place sooner. Morris had been there, observing every aspect of the process, sitting behind Sirhan in court as he would sit later in Shelby County Judge Preston Battle’s criminal courtroom behind James Earl Ray.

“Until he was in the state prison system, he was my guy,” says Morris. “My job was to see he was secure, that he maintained his health, had proper legal counsel, and all the Constitution requires. Plus!”

Among other things, that meant keeping a lid of total secrecy on the time — the wee hours of July 18, 1968 — and the place, the Millington Naval Air Base, of Ray’s arrival in Shelby County. “Nobody but me knew exactly what I was going to do. I had the FBI, I had everybody. I was in communication with the plane.” Morris had assembled an entourage of Shelby County deputies, Memphis policemen, and FBI agents at his then residence in Parkway Village and, at the appointed time, headed north toward Millington “by a circuitous route.”

Once within the heavily secured perimeter at the air base, Morris boarded the plane with an FBI agent and with Dr. McCarthy Demere, a renowned local plastic surgeon and professor of medicine and law, who would administer a quick strip search of Ray after the sheriff read him his rights.

Ray’s post-assassination wandering had taken him as far as London, which encouraged people to believe he must have been assisted in his crime. In reality, though, he was traveling on stick-up money and, down to his last few dollars, had bought a one-way ticket to Brussels, hoping to join up there with white mercenaries he’d heard were on their way to fight black rebels in Angola. As for his Canadian passport, bearing the name of Ramon George Sneyd, an actual Toronto resident whose name Ray had lifted from a telephone book, it had been obtained by merely filling out a form.

Morris took charge of Ray from his Justice Department retainers on the plane, and within minutes, the entire caravan was headed back to Memphis — with a smaller group including Morris, Tennessee Police Director Greg O’Rear, and a manacled Ray aboard an armored tank-like vehicle fitted especially for the occasion.

“I’ll tell you. Nobody had an opportunity to see James Earl Ray in my custody except my people. The thought was, anybody you can photograph, you can shoot,” Morris says. And it is a fact that from the time Ray arrived at the Millington Naval Air Base, until eight months later, on March 10, 1969, when Morris handed him over to Tennessee troopers for delivery to a state prison, there were no cameras trained on Ray that were not under the sheriff’s direct control.

Even so, some word had inevitably gotten out and, by the time the caravan arrived in Shelby County, still before daylight, news media from all over the world were clustered around the site of the Shelby County jail.

“There were maybe 100 media people on the building steps. TV cameras everywhere,” Morris remembers. But they would be frustrated. The sheriff had arranged for a school bus to be pulled up to a back entrance, screening the arrival of Ray and his captors.

If Ray’s passage into custody had been secure, his manner of incarceration was doubly so. “We had welded down all manhole covers within 500 feet. We went extreme,” Morris says. “We had welded metal plates across the bars in the area that included his cell, in case somebody decided to aim missiles at the general area.” An entire floor of the jail was reserved for Ray, who was rotated from cell to cell.

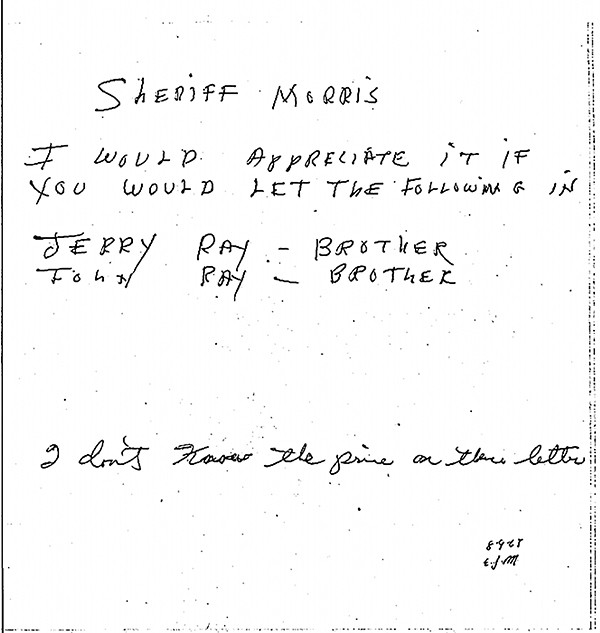

The lights in Ray’s cell area burned 24/7. Cameras embedded in the ceiling recorded his every move. Such was the aura of perpetual scrutiny that entitled visitors, essentially limited to Ray’s counsel and family, were unnerved to the point of lying on the concrete floor and turning on the shower in an effort to prevent being overheard.

Morris smiles at the thought today. “They were entitled to privacy, and they got it,” he insists.

Author Gerald Frank’s 1972 book, An American Death, is one of the three or four most readable and reliable accounts of the King assassination and/or its aftermath (Memphian Hampton Sides’ Hellhound on his Trail, published in 2011, is another.)

Frank, who was on the scene in Memphis throughout the period of Ray’s incarceration and pre-trial proceedings, offers this take on the way the Shelby County Sheriff handled things:

“One had the impression that Morris would be prepared to do away with himself — commit hara-kari were that the sort of thing an American did — if anything happened to Ray; that if an attack came, he would willingly throw himself in front of the prisoner to take the bullets in his own body. The sheriff was the kind of a man who would walk alone down the center of the street in High Noon.”

There is no denyng that all of Morris’ exertion was appropriate. Even the most unregenerate Confederate-minded among us would acknowledge that the violent murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., at the apex of his career and on the eve of what King himself saw as his ultimate mission, the then pending Poor People’s March on Washington, was too large a crime to escape the fullest possible accounting.

Though Morris conscientiously avoided discussing with Ray or anyone else any aspect of the crime, he did spend a good deal of time with Ray. What did they talk about? “Oh, nothing much, just small talk. Nothing racial, for sure. I never saw that in him. It was actually pretty jovial,” remembers Morris. Ray, it seemed, enjoyed making fun of himself, and, for the sheriff’s benefit, rendered accounts of some of his misadventures that had landed him in this or that jail.

“There was the time Ray shot himself in the foot running through an alley after he’d held up a place, and another time he forgot to shut the driver’s-side door of his getaway car and fell out into the street trying to drive away from a hold-up,” Morris recalls, chuckling.

The relationship beween Morris and his prisoner became so comfortable that, when Ray had to return to Shelby County in a vain effort to seek the overturn of his ultimate guilty plea, Morris secreted his prisoner’s departure back to Nashville by dressing him in a deputy’s uniform.

As the car containing Ray headed away from the Shelby County Courthouse toward a planned rendezvous with state police on I-40, Morris cracked a window, and Ray could not resist calling out to a watchful reporter outside the Courthouse, “Cold enough for you out there?” The distracted and unsuspecting reporter, still keeping vigil for sight of Ray, answered back, “Sure is, officer!”

James Earl was a con in every sense of the word, including his undoubted skill at conning people. The last of his several escapes, from St. Joseph Prison in Missouri in 1967, had involved talking his fellow prisoners into loading him beneath stacked loaves in a bread truck.

While he was on liberty from that escape, he zig-zagged across North America, financing his wandering with random hold-ups, traveling in used cars, junk jalopies mostly. He studied bartending at one stop and took dancing lessons at another. A good score in Toronto netted him enough money ultimately to buy the famous “white Mustang” that was seen driving away from the assassination scene.

A redneck always, with redneck views on race, Ray may have let his siblings John and Jerry, known to be in touch with Klan figures and influenced by rumors of bounties for the silencing of King, egg him on to the idea of being a hero (or martyr) for the lost cause of racism.

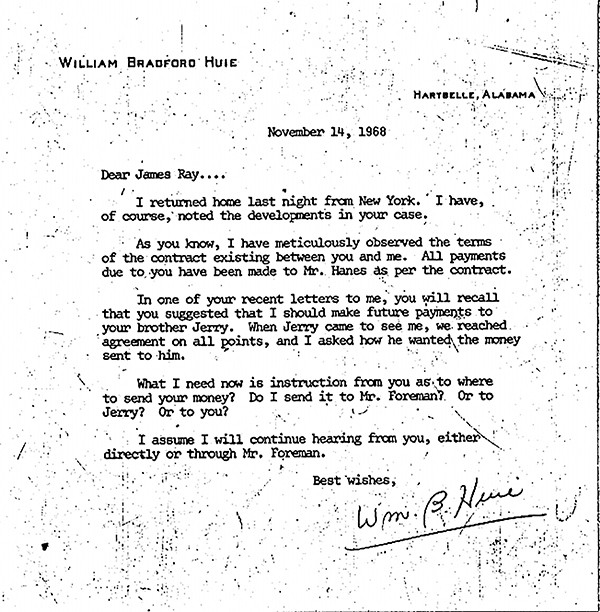

That’s another of several conjectured conspiracies, but all of them were finally deemed either unlikely or beside the point by the credulous luminaries initially drawn to Ray’s cause, including biographer William Bradford Huie and Ray’s earliest legal defenders, the Birmingham legal team of Arthur Hanes Sr. and Arthur Hanes Jr., whose place was ultimately usurped by the swaggering celebrity defense lawyer Percy Foreman.

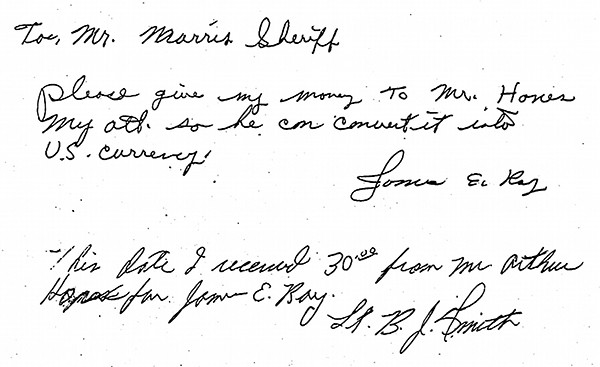

All the attorneys’ fees were paid by Huie, who also subsidized Ray in exchange for what he hoped would be a best-selling tell-all tome. The ultimate product was Huie’s He Slew the Dreamer, which reluctantly concluded, like the lawyers themselves, that the epochal crime had been pulled off by Ray alone, unassisted by anyone including the transparently fictitious “Raoul” dreamed up by Ray for appeal purposes. It fell to Foreman finally to make the formal plea of guilty in the court of Criminal Court Judge Preston Battle.

Within minutes of that plea, Morris had James Earl Ray out the door of the courthouse. He and Ray, accompanied by deputies and shackled together for security, would shortly be at the Shelby Farm penal facilities awaiting transfer to the state.

As they waited at the penal facilities᾽ firing range, Ray offered the sheriff a proposition, prompted by the yard markers located at intervals on the firing range: “Tell you what,” he said. “Just for the sport of it, let me go and give me a head start to that 25-yard mark. I’ll bet you I can make it the rest of the way.” Morris laughed and replied that, having made such a point of denying the media their 50 yards worth of proximity, he could hardly cut Ray that much slack. The transfer went off without a hitch.

Today, Morris remains fascinated by the confluence of circumstances that allowed Ray to pull off the assassination of someone so closely observed as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and, “in the middle of the storm,” to remain at large for as long as he did. And he wonders today if some “collusion” was involved. If so, he says, “I strongly suspect it emanated through his brothers.” But the still extant tribe of conspiracy theorists does not interest him. “It has held no intrigue for me to listen to people with their own agenda.”

Mainly, Morris had been concerned back then to do his duty. “We were under the gun to perform at the highest level of efficiency, to protect the constitutionality and the process of government in this country. Whatever you’re faced with, you man up.” J. Edgar Hoover later thanked Morris for the quality of his service in the emergency, as did the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Dr. King’s friend and successor.

Morris’ immersion in the crisis atmosphere of the time had, among other things, heightened his sense of “the dramatic disparity in the wealth and prospects of whites and blacks” and would drive him, during his later service as Shelby County mayor, to try to close that gap through such means as his path-finding “Free the Children” program.

That, too, as he sees it today, involves an overdue manning up.

Bill Morris, after his service as sheriff, went on to serve four terms as Shelby County mayor and waged a campaign for governor in 1994. His political career was terminated by the misfortune that saw his beloved wife Ann felled by a stroke, though he regards his dutiful service as her caregiver for the past 17 years as the summit of his career.

That career has included, besides his political prominence, service on behalf of the Jaycee and Boy Scout organizations and numerous civic causes, as well as his major role in the transitioning of Shelby County government to its current metropolitan dimensions. Morris’ achievements resulted in a major thoroughfare, Bill Morris Parkway, being named for him in his lifetime — an honor previously accorded only the legendary political boss E. H. Crump and Morris’ friend Elvis Presley, who included him within the King’s “TCB” fraternity of privileged intimates.

On Wednesday evening, April 15th, at Graceland Mansion, Morris will be the honoree at an event chronicling his life and achievements called “Lessons in Leadership: An Evening with Bill Morris.” Proceeds will benefit the Church Health Center Scholars Program. Featured will be testimonials from Carol Coletta, Bill Evans, Harold Ford Jr., Brad Martin, and Fred Smith, and will conclude with a conversation between former Mayor Morris and Dr. Scott Morris of the Church Health Center.