After years of stagnation, Memphis is finally taking major steps toward creating a solar power system.

The news broke last month when Memphis Light, Gas and Water (MLGW) announced it would seek a site to install solar panels and purchase batteries to store electricity.

CEO Doug McGowen said the city-owned utility is seeking proposals to install 100 megawatts of solar generation and up to 80 megawatts of battery storage. The move is significant for Memphis, which trails many Tennessee communities and is far behind other Southeastern cities in developing community solar power.

“In our nation and around our world, our demand for energy will soon outpace our collective ability to meet it,” McGowen said in March. “If we are going to meet our needs here locally and nationally, we need everyone in the game. With today’s announcement, I will tell you MLGW is in the game. We are taking an important, huge first step in helping our community … meet the challenges ahead.”

The development hinges on a tentative “side agreement” with the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) that would allow MLGW to generate some of its own power. MLGW currently gets all its electricity from TVA under an exclusive contract that forbids it from getting electricity from any other source.

That decades-old contract has long stood in the way of MLGW developing solar power. First signed in December 1984, the rolling, five-year contract contains language preventing MLGW from getting power anywhere other than TVA.

MLGW is one of just five local power companies in TVA’s 153-local-utility system that hasn’t agreed to a long-term contract that allows signers to get up to 5 percent of their power from other sources. Some local utilities that have signed those 20-year contracts have left Memphis far behind in developing solar power.

McGowen hopes to change that.

“This does nothing to change our fundamental power agreement that we have with TVA,” he said. “This is going to be a side agreement, an amendment. That is what we will work on together, on something that will work for both organizations.”

Solar power is something MLGW has had in the works for at least two budget cycles. MLGW inserted money into its budget for solar power in fall 2023 when it prepared its 2024 budget. Money was then also included in fall 2024, when it prepared the budget for the current year.

McGowen’s March 5th announcement follows a report in February by the Institute for Memphis Public Service Reporting that detailed the impediment that the TVA contract poses to developing solar power.

“The community needs more energy. The demand is going up. Where are we going to get it? We do not want to burn more fossil fuels, so solar is where it can come from,” said Dennis Lynch, a Midtown Memphis resident and member of the MLGW citizens advisory committee.

“I could imagine many empty blocks in Memphis covered with solar panels and then people signing up to be members and getting reduced rates for electricity, but even that is not allowed in the current TVA contract.”

In 2022, MLGW discussed entering a 20-year agreement with TVA, which would have allowed the creation of its own solar power system. But that long-term agreement was never signed, so the terms of the 1984 agreement remain in place. In May 2023, McGowen announced that the utility would stick with TVA as its power supplier under the terms of the old contract for now.

Was that a mistake?

Not so, said Stephen Smith, executive director of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, a Knoxville-based nonprofit. That is because committing long-term to TVA means Memphis likely could never get out from under TVA’s onerous exit clauses to pursue cheaper and cleaner energy sources, Smith said.

Under the terms of the current contract, MLGW must give TVA a five-year notice if it wants to leave. A long-term contract would require a 20-year notice, which means it would be decades before Memphis could get free from TVA.

“MLGW is losing out on clean energy, particularly solar, due to the fact that they are not independent from TVA,” Smith said. “But I do not think that signing a long-term contract would be worth it. Memphis would lose out by agreeing to stay with TVA for so long.”

One reason is that the 5 percent limit TVA places on its long-term customers is miniscule compared to the potential for solar power in West Tennessee, Smith said.

“MLGW did absolutely the right thing by not signing that long-term contract. Instead, we would like MLGW to start re-negotiating that agreement again and start using the leverage it has to encourage the use of renewable energy,” Smith said.

Baby Steps to Solar

Outlining his 2025 capital improvement plan at the October 2, 2024, MLGW board meeting, McGowen said the utility is doing what it can to move toward solar power by installing a first-ever battery storage system.

McGowen has acknowledged MLGW is prevented from creating its own solar power because of the current TVA-MLGW contract.

“We are still committed to that. I want to get the battery storage rolling first,” he said. “We have some architecture and engineering money allocated for solar. We are working with our partners at TVA to determine how to do that in the constraints of our current contract. That remains a priority for us.”

Solar power would be part of what McGowen called “an aggressive expansion of capacity” to provide electricity for Memphis. At an MLGW board meeting on February 5th, McGowen noted that the request for proposals for the battery storage would be out soon. But he offered no exact timetable. McGowen has said Memphis needs to expand its ability to provide electricity in order to support economic growth.

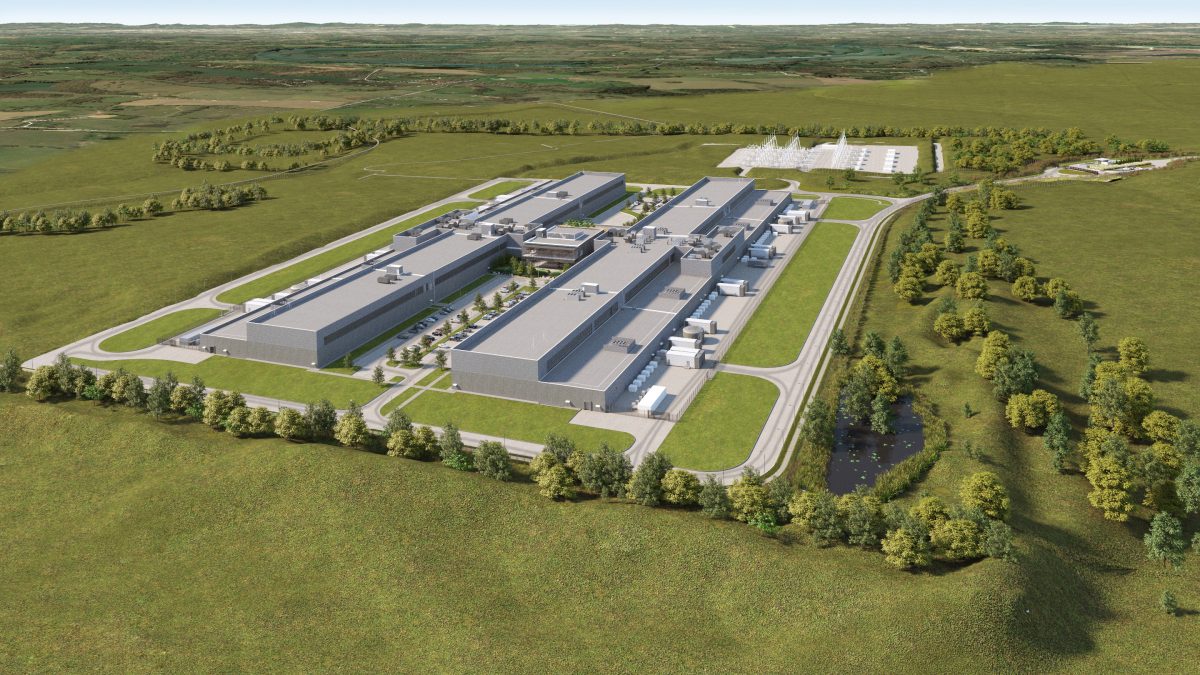

The best example is the establishment of the xAI facility in south Memphis, which has huge power demands. Bloomberg News reported that new artificial intelligence data centers can be drivers of economic growth for communities, but they have huge power demands. Communities that are prepared to provide increasing amounts of electricity will be the beneficiaries. And part of providing increasing amounts of electricity is that local communities need to be generating their own power instead of just buying it from someone else.

Battery storage is pivotal to plans for implementing solar power at the utility scale because the sun does not shine at night, so the electricity must be generated during the day and then stored for use at other times. But a battery storage system is only the first step toward using the sun to generate electricity.

Memphis Falling Behind

Scott Brooks, senior relations specialist for TVA, confirmed via email that Memphis is way in the minority when it comes to developing its own power generation, writing, “Many of our partners are doing solar and community solar.”

Other TVA communities that are generating their own solar power are the Knoxville Utilities Board, BrightRidge (which serves the Tri-Cities area of Tennessee), and the Nashville Electric Service.

A 2023 study done by the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy titled “Solar in the Southeast” confirmed that Memphis was behind Knoxville and on par with Nashville when it came to using electricity generated by the sun.

The same study showed that Memphis will be even further behind Knoxville by 2027 if things stay the same with the TVA contract. And Tennessee, which is almost entirely served by TVA, is miles behind the average utility in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

The goal of creating Memphis’ own solar power system is not new. It was part of the Memphis Area’s Climate Action plan written in 2020. That 222-page plan said: “Transforming our energy supply over the next 30 years will need to take an ‘all-of-the-above’ approach, with actions ranging from partnering with TVA to increasing renewables in their portfolio, to encouraging and constructing local sources of renewable generation (particularly solar).”

The plan said the city of Memphis and Shelby County would work with TVA to explore changes to the MLGW contract. The report mentions solar power 35 times as a key goal for the community.

Yet more than five years since that report, no substantial progress had been made toward establishing a local solar power system in Memphis.

Some solar power exists

Despite the restriction, solar power is not absent in Memphis. The TVA contract does not prevent companies, individuals, or even government entities from putting up solar panels and generating power. One of the most visible solar projects in Shelby County is happening at the Agricenter International, where thousands of vehicles whiz by five acres of solar panels on Walnut Grove Road.

That project, launched in 2012, is generating enough electricity to power 110 homes per year. And it is connected with TVA’s system, showing the potential for solar power in Memphis. The Shelby County government also generates electricity with the establishment of its modest collection of solar panels off of Farm Road behind the county construction code enforcement office.

How can Memphis start maximizing the benefits of solar power?

Citizen action is what is needed to change the situation, says Lynch, a frequent public speaker at MLGW board meetings and member of the West Tennessee Sierra Club.

“Citizens need to better understand what is the story,” Lynch says. “They need to knock on the doors of MLGW and ask MLGW, ‘What are you doing to allow TVA to allow us to install solar?’”

At the March 5th announcement, Mayor Paul Young specifically thanked TVA for agreeing to allow Memphis to move forward with solar power. And he acknowledged how Memphis has been behind when it comes to solar power and creating sustainability energy.

“We know that power is one of the utmost concerns for people throughout this nation. We are thinking about ways to do this with more sustainability, cleaner, thinking about ways we can limit our impact on the environment,” Young said. “This is such an important step. I cannot say enough about how many strides MLGW has been taking.”

Young cited reliability as a key. Solar power and the batteries to store that power help a community keep the electricity flowing during blackouts, storms, and natural disasters.

Mike Pohlman, MLGW board chair, also acknowledged that Memphis has been behind in creating solar power. He said the board has been pushing MLGW for years to get moving on solar power.

“We have gotten out of the pace of snail. And things are happening a lot quicker. We have been looking at this solar thing for two years now. It is finally coming to fruition,” Pohlman said.

McGowen said the proposals for solar generation and battery storage are due back to MLGW by the end of April. He said the goal is to start producing and storing electricity by the end of 2026. MLGW has not yet identified a site for the solar facility.

Tom Hrach is a professor in the department of journalism and strategic media at the University of Memphis. He has a doctorate degree from Ohio University and has more than 18 years of full-time experience as a journalist.

The Nuclear Option

Earlier this month, the future of energy development in the Tennessee Valley was thrown into uncertain territory. TVA is owned by the federal government, having been established in 1933 during the first wave of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation. Its original purpose was to electrify the rural areas of Tennessee, which had been neglected by for-profit electric utility companies who feared the high cost of building thousands of miles of electrical transmission infrastructure to serve a relatively small population in what was at the time the most impoverished region in the country. These days, TVA receives no taxpayer money and operates by selling electricity to ratepayers like a privately owned utility company.

But the executive branch still has control over TVA’s board of directors, and in April, the Trump administration removed two board members, Michelle Moore and Board Chairman Joe Ritch. No reason was given for their removal. The board usually consists of nine members, but with the removal of Moore and Ritch, only four remain. That means that there is no longer a quorum on the board, effectively paralyzing the $12 billion organization which provides power for more than 10 million people.

Shortly before the firings, the board appointed Don Moul, the utility’s former chief operating officer, as the new president and CEO. After the firings, Justin Maierhofer, a longtime TVA executive, was appointed as chief of government relations. A new Enterprise Transformation Office, created by an executive order from President Trump, will seek to reorganize the utility’s leadership structure, according to reports from Knoxville News Sentinel. The office will seek at least $500 million in savings to make way for building new generation capacity.

What, if any, effects this shake-up will have on MLGW’s solar power plans are unclear. But if Tennessee senators Bill Hagerty and Marsha Blackburn have their way, TVA’s focus will not be on solar but on nuclear energy. This is familiar territory for TVA, which was a pioneer in civilian use of nuclear power in the 1960s and ’70s. But the utility’s nuclear program has stagnated, thanks to ballooning costs for building huge power plants like the one at Watts Bar in Spring City, Tennessee, where the last new reactor came online in 2016 after decades of development and construction.

In an op-ed published in Power magazine, the two senators call for TVA to invest in a new fleet of nuclear power plants which would be smaller and easier to construct than the mammoth facilities the utility currently operates. “With the right courageous leadership, TVA could lead the way in our nation’s nuclear energy revival, empower us to dominate the 21st century’s global energy competition, and cement President Trump’s legacy as ‘America’s Nuclear Energy President.’” — Chris McCoy

Southern Alliance for Clean Energy

Southern Alliance for Clean Energy  MLGW

MLGW

Clewisleake | Dreamstime.com

Clewisleake | Dreamstime.com  Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority