One of the strangest interludes of the soon-to-end 2013 legislative session occurred last Thursday, April 4th, at the very beginning the state Senate floor session, just after the ritual invocation and pledge of allegiance. Pledges, rather — since, as of the current session, both the standard pledge of allegiance to the United States and the relatively unknown pledge to the state flag of Tennessee are recited, in that order.

State senator Stacey Campfield of Knoxville, who is either a carrot-top prankster, a radical change agent, or a threat to human values, depending on one’s vantage point, sought attention from the speaker, Ron Ramsey. In this case, Campfield chose to materialize as, of all things, a dedicated Unionist. “I know we’re all for states’ rights,” he began. But he challenged the current order that had members doing the federal pledge first and the state pledge after, contending that “the American flag takes precedence over all other flags” and that the Senate should “highlight” the pledge to the American flag by saving it for last.

Given that Campfield is, like Ramsey himself, part and parcel of a Republican majority that rarely misses an opportunity to declare Tennessee’s independence from federal authority, this was rich.

He was answered in short order by Senator Douglas Henry, a venerable Nashville Democrat and a survivor of his party’s once-dominant Tory Old Guard. Speaking in his mellow molassified drawl, Henry said he considered Campfield “technically” right but objected that it “pained” him to see the Tennessee flag “dipped” to the American flag, which was something that should never be.

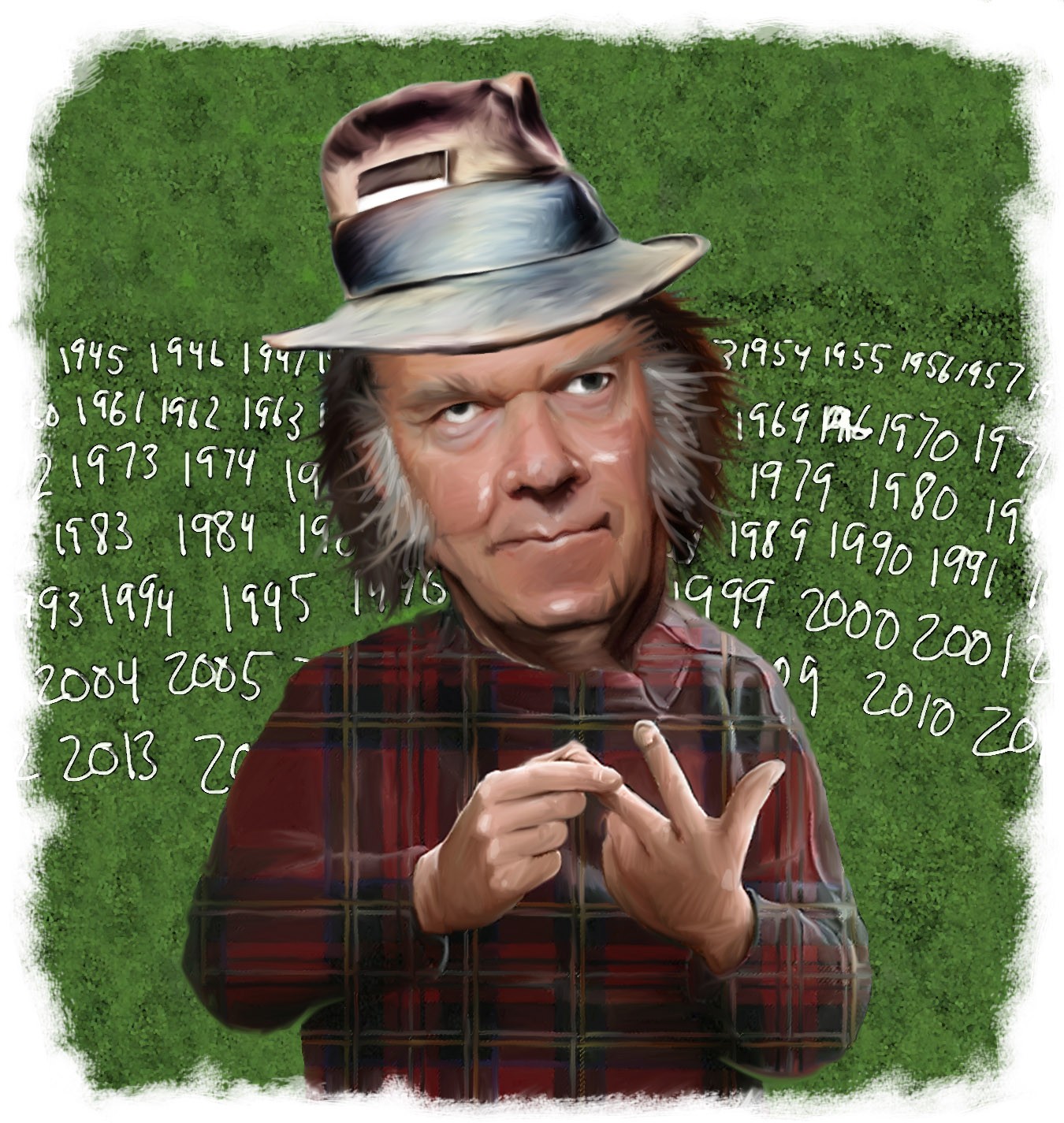

Speaker Ramsey next recognized a fellow East Tennessee Republican, Senator Frank Niceley, a gentleman farmer from Strawberry Plains who had earned his share of headlines recently — first by proposing that public primaries for Tennessee’s two U.S. Senate seats be scrapped in favor of nominations by the General Assembly, the way things were done before modernity began to wreak its wicked ways in 1913 (a year that also saw the enactment of a federal income tax), and then by citing the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, as his authority against a bill that would outlaw cockfighting.

“What did Abraham Lincoln think about this?” Ramsey asked now, tongue clearly in cheek. But Niceley explained that his source, this time around, was Robert E. Lee, whom he cited as having considered himself a Virginian first and an American second, concluding, “If Robert E. Lee was a Virginian first and an American second, I’m a Tennessean first and an American second.”

The issue — one of “etiquette,” as Ramsey referred to it in his end-of-week press availability later that day — was not resolved either then or later, but the general theme of state vs. federal was returned to in that day’s climactic action in the Senate when state senator Brian Kelsey (R-Germantown) rose on behalf of his Senate Resolution 0017 regarding “Firearms and Ammunition,” the caption of which went this way: “Expresses the will and intention of the senate to resist any effort by the federal government to restrict or abolish rights that are guaranteed to the people by the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

If that wasn’t explicit enough, Kelsey’s opening remarks encased the central issue of the resolution neatly: “Senate Resolution 17 is a very important resolution, because it says, if the federal government tries to infringe on the Second Amendment rights of our citizens, then we will intervene, and we will fight for those rights on behalf of Tennesseans.”

As incendiary and Fort Sumter-like as that might have sounded to the uninitiated, Kelsey was actually speaking as a voice of relative moderation. As he explained, for the benefit of “those who think the resolution is not strong enough … this is America, this is not Benghazi,” and he was advocating defiance of federal writ through ordinances and resolutions, “through the rule of law.”

The point was made clearer when another Shelby Countian, Majority Leader Mark Norris (R-Collierville) rose to ask if this was “the same legislation that Senator Beavers had.”

It wasn’t, of course. Senator Mae Beavers (R-Mt. Juliet) rose to explain that her earlier bill, SB 250, had provided merely for arresting agents of the federal government who were rash enough to try to enforce any pending federal gun legislation, “not shooting them,” as she thought Kelsey had just implied. Her bill had been one of the relatively rare ones that had been too far right for this session of the General Assembly to approve. Like a similar bill by state representative Joe Carr (R-Lascassas), which would declare federal gun legislation “null and void” in Tennessee, it failed to advance in either chamber.

Indeed, at that early point in the 2013 session, it had fallen to Kelsey to enlighten Beavers on her faulty understanding of the Constitution and the failure of nullification efforts by states. And now, his substitute Senate resolution with its tamer version of defiance passed 17-0, with the few Democrats merely abstaining.

This is how debates run in the age of Republican supermajorities in the Tennessee General Assembly: Spokespersons for the right contend with those for the super-right.

The term “supermajority” means that the GOP decides all matters. There aren’t enough Democrats left to challenge them. This is the result of a trend, already underway, that accelerated — oddly, or perhaps understandably — in 2008, the year of Barack Obama’s “Yes, We Can” election in the nation.

There are 26 Republicans and seven Democrats in the state Senate; 71 Republicans, 27 Democrats, and 1 Independent in the House. The Independent, Kent Williams, is technically a Republican, but he was officially purged from the GOP caucus for the sin of accepting Democratic support to be House Speaker in 2009.

For the record, that was virtually the last time Democrats were able to mount any sort of rally against Republican domination, and it was a telling irony that it was by means of elevating Williams, a GOP moderate who is now and forevermore a powerless back-bencher, like the Democrats who befriended him.

The Democratic presence was further minimized by the Tea Party election year of 2010 that returned overwhelming Republican majorities. It was those majorities that controlled redistricting after the Census of 2010, redrawing the election maps so as to ensure one-party government for at least a decade.

These days, Democrats are basically reduced to a hope that Republicans might get in each other’s way, canceling out this or that GOP initiative through intramural strife.

Something like that happened last week, when a squabble between Republicans apparently sidelined the likelihood of legislation this year apportioning a share of the public purse to private schools via state-issued vouchers. A pilot bill toward that end had been proposed in his State of the State address in January by Governor Bill Haslam, a smiling, friendly countenance, who, like House speaker Beth Harwell of Nashville, can be said to represent the traditional conservative wing of the Republican Party, as opposed to an ultra-conservative wing. (Nobody, but nobody, in the GOP is any longer willing to be called a “moderate.”)

Haslam’s bill would have allocated enough funding to provide modest-sized vouchers for 5,000 low-income students currently enrolled in schools certified by the state as failing. The aforesaid Kelsey, who had first proposed similarly sized vouchers under the name of “opportunity scholarships” in the 2011 legislative session, at first had indicated he was onboard with the governor’s proposal, but as the Haslam bill advanced, carried by majority leaders Norris in the Senate and Gerald McCormick (R-Chattanooga) in the House, Kelsey and fellow senator Dolores Gresham (R-Somerville) developed greater ambitions for a voucher system, hoping to expand it to children in families making as much as $75,000 a year and ultimately enlarging its scope to cover a less narrowly defined range of schools.

The resulting tug-of-war between Republican factions resulted last week in summit meetings between GOP leaders that failed to reach agreement. Haslam, a first-term executive elected in 2010 after several years’ service as Knoxville mayor, had drawn criticism during his first couple of years in Nashville for yielding too much ground to his party’s hard-liners. He had allowed Ramsey to insert a bill abolishing collective bargaining for teachers into his program for education reform, and only the week before the governor had bowed to the apparent wishes of the Assembly’s conservative majority to opt out of federal funding for Medicaid expansion in Tennessee.

Now, however, he had drawn a line in the sand. And, rather than yield on the voucher issue, he had his bill withdrawn altogether. Gresham, it turned out, had been willing to defer to the governor, but Kelsey had not, and even Ramsey, whose support the Germantown senator had perhaps been counting on, backed the governor instead, telling reporters last Friday, “I think something’s better than nothing. Sometimes, the search of perfection stands in the way of good.” Kelsey, he said, had been “bound and determined” to push for a bigger voucher program, and that had been that.

Regarding Kelsey’s expressed wish to attach amendments on behalf of vouchers to other last-minute bills, Ramsey was firm. Any such legislation should pass through the two chambers’ education committees, both of which had shut down for the year. He was dead set against anyone attempting to “hijack” another Senate bill.

The bottom line was that Kelsey had to take his lumps. It was a meaningful rebuff in that the Germantown senator had been riding high, indeed. He has successfully pushed through both houses a proposed Constitutional amendment against any possibility of a state income tax, one that will apparently be on Tennesseans’ ballots in 2014.

And, on the very day, the week before, that Haslam had been forced to acknowledge that expansion of Medicaid (TennCare, in Tennessee’s version) was “too steep a hill” to climb, Kelsey had pushed a bill in the Senate commerce committee that Haslam had asked him to desist from. The bill, SB 0804, was written so as to “prohibit … Tennessee from participating in any Medicaid authorized under the Federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” and even continued a clause saying the governor “shall not make a decision nor obligate the state in any way” to that end.

The bill’s wording was slightly altered in committee so as to be less provocative, but Kelsey had successfully hurled his defy. And now Haslam’s action on the voucher matter was in many quarters being taken as an overdue assertion of gubernatorial authority against overreach by Kelsey and, by extension, the legislature in general.

It was probably overreach, too, when former state senator Roy Herron, the new chairman of the state Democratic Party, hailed the temporary derailing of voucher legislation this way in a press release: “This is a huge win for our state and for our Democratic legislators (and a few reasonable Republicans) who have been fighting hard to protect our public schools — and our children’s future!”

The reality may be far less exalted. In the wake of the voucher bill’s being pulled, word was getting around Capitol Hill that the real problem was that voucher legislation would prove to be a boon to private Muslim institutions, who might use voucher funds on behalf of God knows what kind of mischief. This mollified the enthusiasm of Republican legislators for vouchers, especially state senator Bill Ketron (R-Murfreesboro), Republican caucus chairman and author of various legislative efforts — notably the infamous “Sharia” bill of 2012, which was ultimately watered down — that were designed to counter what was seen as undue Muslim influence in the affairs of Tennessee.

As Senator Jim Tracy (R-Shelbyville) put it, “This is an issue we must address. I don’t know whether we can simply amend the bill in such a way that will fix the issue at this point.”

This kind of motive cannot be overlooked in any consideration of the Tennessee General Assembly in 2013. There was, after all, the famous mop-sink scare.

The venerable Capitol building has been undergoing extensive renovations this year, and one of them had become a source of alarm to Ketron and state representative Judd Matheny (R-Tullahoma), another legislator concerned about Muslim influence, both of whom inquired as to whether a new water installation in the second-floor Capitol restroom, stretching from the floor halfway up the wall, had been designed to accommodate Islamic foot-washing rituals. Building administrator Connie Ridley responded succinctly to their concerns: “It is, in laymen’s terms, a mop sink.”

That story, uncovered by the AP’s Eric Schelzig, went far and wide, inspiring wags and pundits everywhere. Comedy Central’s Stephen Colbert, in particular, had a field day, lampooning the “terrorist footbath” that was discovered in the Tennessee Capitol and chanting “Osama Been Moppin’!”

The mop-sink incident has not been the only source of humor generated by the current legislature.

The aforesaid Stacey Campfield has been the author of much legislation that has provoked chuckles (albeit often of the kind implicit in the hoary old punchline, “It only hurts when I laugh.”). He designed a bill in 2011 that became nationally known (and satirized) as “Don’t Say Gay,” in that it would have prohibited any discussion of homosexuality in Tennessee’s elementary schools.

As modified and transformed, it still persists as the “Classroom Protection Act,” which died quietly this year in the House. Still hanging fire is another Campfield creation, SB 0132, which also lends itself to a caricature title, “Starve the Children.”

But who’s laughing? The bill, which would reduce state aid to impoverished families if students in those families failed to make their grades, could not be deflected by the few Democrats who publicly opposed it. And, softened somewhat, it was even acquiesced to by the state’s Department of Human Services.

Rolled last week, it was due for floor consideration in the Senate this week.

With less than two weeks to go before a scheduled adjournment date of April 19th, the fate of a number of bills remains unknown.

Among them are several bills of considerable interest to Shelby Countians following the ongoing school-merger issue. They include SB 1363/HB 1288, the latest version of Norris-Todd legislation, which would allow the long-deferred creation of municipal school districts. Unlike a similar bill which passed the legislature in 2012 but was declared unconstitutional by U.S. District Judge Hardy Mays, this version is written so as to apply statewide and in order to avoid a similar fate.

That bill is headed to the Senate calendar and will undoubtedly be voted on before adjournment. The same is true of SB 1354/HB 1291, which expands the number of allowable LEAs (local education authorities) in a county from six to seven, thereby making room for all of Shelby County’s suburban municipalities to form school systems.

Another bill, SB 830/HB 702, which would create a new state charter-authorizing panel able to bypass local school boards in the approval process for new charter schools, is scheduled for imminent action in the finance committees of both chambers and may also make it to floor consideration.

There are other weighty matters making their way to final decision, and there are other matters that have already been disposed of. The unlucky Ketron has seen one of his pet measures, SB 285, the “Animal Fighting Enforcement Act,” killed in the Senate’s calendar committee.

This is a bill that would have banned cockfighting but which was resisted by, among others, the previously quoted Senator Niceley, who had, as Speaker Ramsey indicated, invoked Abraham Lincoln as a supporter of cockfighting, whether accurately or not, and saw the bill as an assault on animal agriculture in much larger ways.

“This bill is not about chickens,” the victorious Niceley declared in the climactic Senate debate, deigning not to add a suffix to that noun that may have more adequately described the legislative process in this session of 2013.

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens