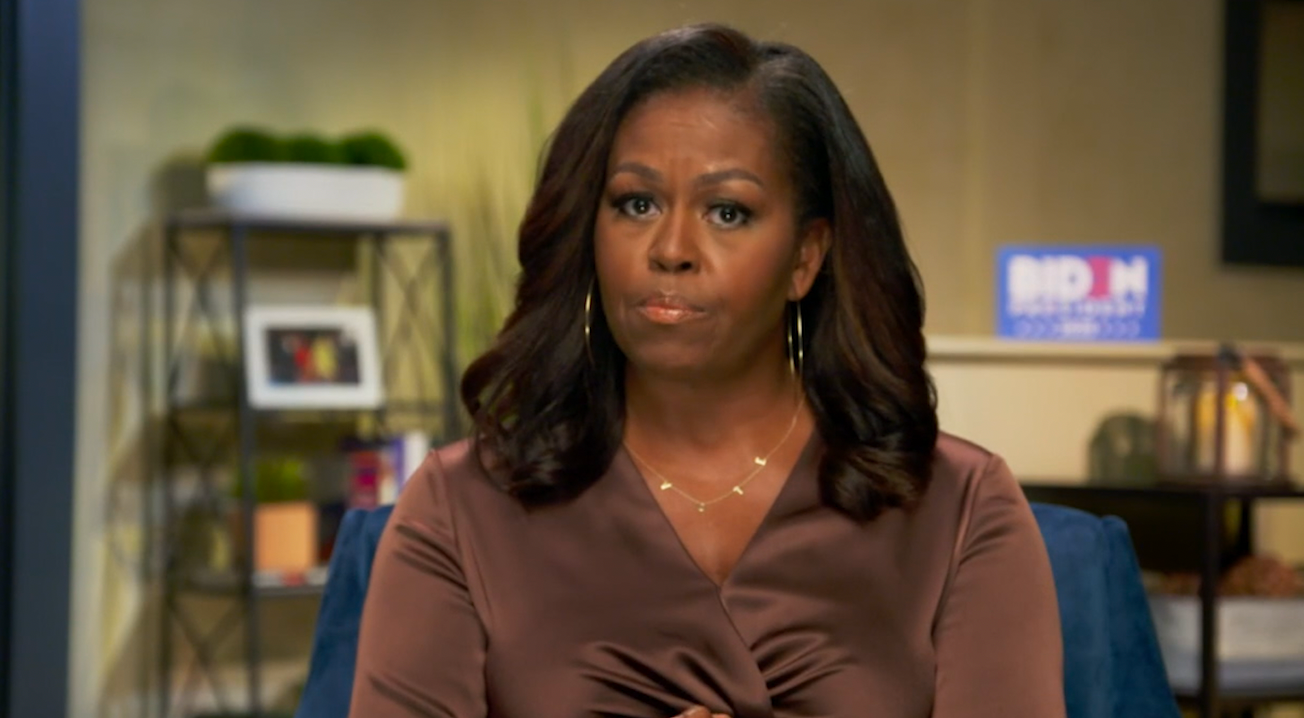

Michelle Obama speaking on the first night of the 2020 Democratic National Convention.

American democracy is messy, and it always has been. In fact, it could be argued that disorderliness is a feature, not a bug, of the Founding Fathers’ system.

One of the messiest aspect is the political nominating convention. They didn’t exist in the time of George Washington. Overtly campaigning for the presidency was seen to be uncouth, as Alexander Hamilton notes about Aaron Burr in Hamilton. Parties, themselves a concept Washington despised, chose their candidates through caucuses — the mythical “smoke-filled rooms.” But in 1831, the anti-elitist, conspiratorially minded Anti-Masonic Party decided to choose their candidate in the open. Andrew Jackson thought that sounded like a good idea, and the first Democratic convention took place the next year.

The conventions became a quadrennial gathering of the party faithful. Sure, most of the decisions were made by power brokers in the smoke-filled rooms, but delegates loved to get together and hoist a few brews while talking politics. It was a good bonding ritual for the parties, and entirely in character for a country whose founding revolution was hatched and planned in the taverns of Philadelphia and Boston.

Eventually, as democratic spirit spread, state-level primary elections developed. The delegate system was similar to the now much-despised Electoral College: Voters chose a slate of delegates who would then go to the national convention to cast proxy votes for their candidates during the roll call nominating session. Thus, John F. Kennedy was elevated by the grass roots in 1960. But the conventions were still the last word, and it was — and remains, at least theoretically — possible that convention wheeling and dealing could yield a different candidate than who won the primary vote. This is what happened during the Democratic fiasco of Chicago 1968, when Robert Kennedy was assassinated after winning the California primary, and the anti-Vietnam War Eugene McCarthy, who held an lead in pledged delegates, was passed over in favor of Hubert Humphrey, who hadn’t received a single primary vote. The party was bitterly divided, and Humphrey went on to lose to Richard Nixon. Since then, other attempts at old-fashioned convention shenanigans, such as Ronald Reagan’s run at Gerald Ford in 1976, have fizzled.

The modern convention is a coming out party for the candidates, and an opportunity for ambitious young politicos to get some exposure on the biggest possible stage. The conventions routinely attract the largest audiences of campaign season, doing not-quite Super Bowl numbers, but close, even in our fragmented media world. As such, the conventions have become made-for-TV spectacles with a political par-tay attached.

But here in 2020, the coronavirus pandemic has made gathering the party faithful in a big arena an extremely bad idea. Who is going to conduct a campaign if an outbreak lays low your cadre of enthusiasts? Faced with an unprecedented problem, the parties were forced to scramble for solutions. Being the party out of power in the White House, the Democratic Party went first. Instead of gathering en mass in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, they did what everyone else has done: gone virtual.

Children singing the national anthem at the 2020 Democratic National Convention

This could have been a disaster. Indeed, I was expecting a disaster when I tuned in for the first night of the Democratic convention on Monday. The festivities kicked off with a virtual “Star Spangled Banner” sung by a chorus of children who appeared only in separated images resembling a giant Zoom chat. It was a little corny, but hey, we’re talking about a political convention here, not a Cardi B show.

(Man, it would be great to be able to go to a show right now.)

For everyone who has ever had their Zoom meetings delayed by participants trying to figure out how to unmute themselves or bandwidth issues slowing conversation to a crawl, glitches are an expected feature of business and social gatherings. But aside from the occasional minor hiccup, the virtual Democratic National Convention has gone smoothly.

It has also been unexpectedly compelling, in a way that is tough to put a finger on. There is a certain primal power in a mass rally, with shoulder-to-shoulder masses cheering a single champion, elevated on a pedestal. The first person to exploit that power in moving images was none other than Adolph Hitler. With the help of his favorite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl, he used the Nuremberg rally of 1935 to deify himself to his followers. The response in democratic societies has been mixed since the defeat of fascism in 1945. Punk rock, for example, was in its own way a response to the fascistic spectacle of arena rock. Donald Trump, more than any contemporary politician, understands the power of the rally, both to energize his followers and attract the cameras of national media outlets. But this virtual Democratic convention has seen none of that. If the Democrats are trying to differentiate their brand from Trumpism, it has worked. Instead of Trump’s seething ball of white nationalist resentment, nominee Joe Biden has been seen sitting calmly on a teleconference, listening to the problems of average Americans.

The lack of a podium has been a great equalizer. Normal people, like Amtrak conductor Greg Weaver and elevator operator Jacquelyn Brittany are exactly the same size as political power players like Bill Clinton and Chuck Schumer. There’s something bracingly honest about seeing the best speaker of the convention so far, Michelle Obama, deliver her impassioned plea for national sanity while sitting alone, just like everyone else. The convention is speaking the painfully familiar visual language of the Zoom call. The keynote address took advantage of the form by editing together 14 speakers, including Memphis-area state Senator Raumesh Akbari.

The keynote address, featuring Georgia’s Stacy Abrams (center) and Tennessee state Senator Raumesh Akbari (top right)

Best of all has been the Roll Call, the tradition where the delegates from each state are called on to formally enter their vote for the nominee. Normally, this would done on the convention floor, with delegates in funny hats shouting “The Hoosier State casts 11 votes for Bernie Sanders and 89 votes for Joe Biden!” into microphones. For the virtual convention, delegates picked spots in their states and delivered the votes virtually. The first voters, from Alabama, cast their votes from the Edmond Pettus Bridge in Selma, where the recently mourned John Lewis and other civil rights marchers were beaten to within an inch of their lives on Bloody Sunday. Puerto Rico’s delegates delivered their votes in Spanish. The lone Kansan spoke from the middle of a field. Rhode Island used the opportunity to introduce America to its state dish of calamari. The whole affair distilled the essence of American democracy: The real power rests not with the bigwigs, but with the normal people in their little towns, giving their consent to be governed, not ruled. The form may be different out of pandemic necessity, but it has proved unexpectedly poignant.