Dancing his way into his third major-label album cycle, megastar rapper Hammer, who’d only recently dropped the “MC” prefix, released the bombastic “2 Legit 2 Quit” single and video. The song served as a not-so-veiled retort to critical voices from within a growing hip-hop music fandom whose appetite for harder-edged reality rap had begun to shift the archetype of success in the genre. While this renewed and rejuvenated Hammer returned with one of the most expensive and glitzy videos of popular music history — a 15-minute production with staged explosions and a dizzying array of celebrity cameos — he came across as a tougher, more street-wise version of himself. As the party winds down in the song’s latter half, Hammer pauses for a dance break, offering a repetitive chant of “Get buck!” to the beat.

What would’ve been an innocuous phrase to almost all who heard the 1991 song, a platinum seller that peaked at No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100, was a dog whistle to rap fans in Memphis, Tennessee. It especially pricked the ears of Pretty Tony, who’d help popularize the chant at numerous talent showcases in the city, releasing his own single titled “Get Buck” on a cassette the year prior.

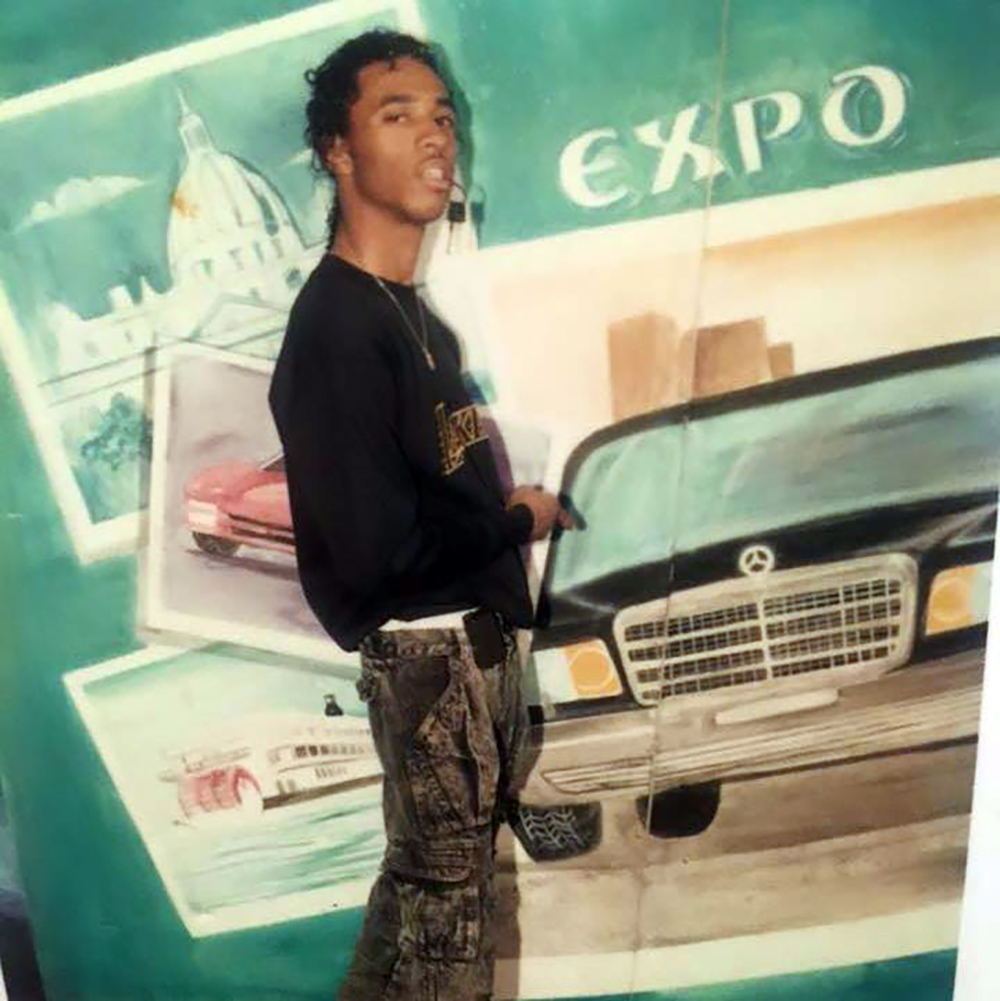

“I wrote ‘Get Buck’ in 1986. But I didn’t drop it until 1990,” Tony, whose real name is Anthony Davis, says. “I saw something missing in hip-hop, a real, raunchy club sound that wasn’t in the industry.” That sound, he says, was his own attempt to capture the atmosphere of Memphis’ fledgling underground rap scene, where a crop of young performing artists and producers converged with larger-than-life street jocks, whose mixing and hosting skills circumvented the conventions of commercial radio. Behind the doors of night spots like Club Expo, Studio G, and 21st Century, major players provided a proving ground for a new style of rap, and everyone involved worked to find their own way to get it on tape.

Much like the origins of its older, more established siblings in New York and Los Angeles, the Memphis hip-hop contingent had been born as an offshoot of a nightclub culture where disco and funk had only recently given way to a slick, synthesized sound.

Trumpeter and Somerville, Tennessee, native John Moore credits the shift for changing the course of his life. Setting his sights on Memphis, immediately after graduating high school, he jokes that he was hanging outside Stax Records before his school band could finish “Pomp and Circumstance.”

Shortly after that day in 1974, he began to notice that splitting money on a bandstand in small local clubs was not an easy living. “When disco came, the bands started using keyboards to replace the horns. So the Memphis horn sound wasn’t as valuable as it used to be,” Moore says.

With the global dance craze beckoning eager partygoers in clubs across the city, Moore answered the call, enlisting as a DJ at Club Expo on Lamar Avenue. “To me, it was a no-brainer because if I can get 1,000 people in line to see two DJs, I was better off than having to split $200 with 20 guys in a small club,” he says.

“During the disco era, we, pretty much, put bands out [of business]. That was before hip-hop came in. But it was on the way.”

Beginning his tenure behind the turntables with a DJ named Soul Searcher, Moore, who is renowned locally by his moniker Disco Hound, began to recruit other mixers and personalities to increase Club Expo’s profile. Soon, his core of street jocks would include a young DJ Spanish Fly; a Chicago import named Soni D, whose progressive disco stylings introduced Memphis to an early iteration of house music; and a fast-talking lifelong media man and lightweight insult comic known as Ray The Jay.

“A lot of club owners were against me for fear that they’d lose their clientele with rap coming in,” Ray The Jay says. “And a lot of the club DJs were doing what club owners told them to do. And the radio DJs couldn’t play it because they were doing what their program directors said. But we got it so hot in the club that [if you came late], you’d only be able to stand at the back.”

Born Jay Raymond Nealy Jr., in Little Rock, the child who would become known as Ray The Jay spent his formative years in Chicago with his father. But injuries sustained in an automobile accident prompted his mother to move him back South. As a student at Little Rock Central High School, he played basketball alongside future football coach Houston Nutt. In his junior year, he completed a vocational training program that certified him as a licensed radio broadcaster. His special endorsement also certified him to read radio transmitters. The precocious teenager quickly found work on a local radio news program. Just as swiftly, his trajectory was derailed by robbery charges for a crime he maintains he was falsely accused of committing. Today, Nealy states he wasn’t even in the area of the incident when it occurred. Nevertheless, legal troubles sullied his reputation with college basketball scouts, and Nealy finished his senior year intent on making his mark on-air, studying radio, TV, and film with a minor in sales at Memphis State University.

In time, his voice would cut through. Even today, he can recite his common opening, “News and information continues from WMC in Memphis. I’m Ray Nealy, and here’s what’s happening today!” While partying as hard as he was working, he took a colleague up, partly on a dare, to buy his way into a small after-hours spot called The Golden Nugget on South Bellevue, rebranding the club as the deliberately on-the-nose All Night Disco. His knack for radio gave him an in, as he took to cutting commercials with his signature flair. However, it was his penchant for promotions that took over when he began marketing gimmicks for each night of the week. And, when his DJ didn’t show for a gig, his showmanship won out and he created the Ray The Jay persona to entertain his guests. When his business arrangement at All Night Disco came to an end, he’d hone his repertoire during a brief stint in New Orleans’ French Quarter. After the hiatus, he returned to Memphis nightlife, bouncing from club to club for close to a decade, until he found a home at Expo. On its dance floor, rap was already beginning to bubble.

“All the locals came up with their own songs,” Nealy says. “As soon as they gave it to me, I would play it. If it was good, we’d jam it. If it wasn’t, I’d talk about they ass! I used to check people.” His early favorite, a Westwood rapper named Travis “Homicyde” Townsell, emerged as an influential figure in Memphis’ early rap circle.

“Homicyde was going from one hood to the next hood, promoting the rap and putting on shows,” Nealy says.

“Homicyde was the first gangster rapper I’d ever heard,” says producer, rapper, and multi-instrumentalist Tyrone “Psycho” Bell. “He had that passion when we were just teenagers.”

Bell, who tried his hand at everything from guitar to piccolo in his school band, moved from South Memphis to Westwood with his family as a teenager. After school, he’d rush home to tinker with four-track recorders, making demos of the ditties he came up with in solitude. With his window open, the sound permeated the streets of his new neighborhood.

“The next thing you know, I’d have a yard full of people at my bedroom window,” he says. The ring leader of the small audience was Homicyde, and he wanted in on the experience. Joining with other top rappers in the neighborhood, Homicyde and Psycho formed America’s Most Wanted and signed with a manager. Naturally, Homicyde’s twisted, deranged lyrics proved too violent, and Psycho’s ambitious production technique eventually left them on the outs with management and group mates.

“They call me insane because I’m homicidal, fuck Roger Rabbit, Charles Manson is my idol,” Homicyde would rap on the track “Paranoid,” the early ’90s song that he points to as the launching point of his solo career.

“When we were in America’s Most Wanted, we’d rehearse outside with speakers. People would come and say, ‘This shit is amazing,’” Homicyde says. “But after I put the little gangster touch to it with ‘Paranoid,’ everything just skyrocketed, as far as the [more sinister] Memphis sound.”

Both Homicyde and Psycho would leave the group to mentor, influence, and team up with other known quantities in the Memphis rap canon, with Homicyde working closely with the camp that included the likes of Skinny Pimp, DJ Paul, and Juicy J, and Psycho starting a new group called Men of the Hour featuring an emcee named Al Kapone.

On The Strength (OTS) Records CEO Reginald Boyland notes that the switching around of artists from group to group became emblematic of a scene still finding its footing. In it, the roles of the individual artists at this primitive stage had little priority over the whole. “All these cats were around each other, and they really were friends,” Boyland says of the camaraderie of Memphis rap’s early period. “They were young, ambitious, and they were like brothers, and they stayed out of trouble because they had somewhere to go.”

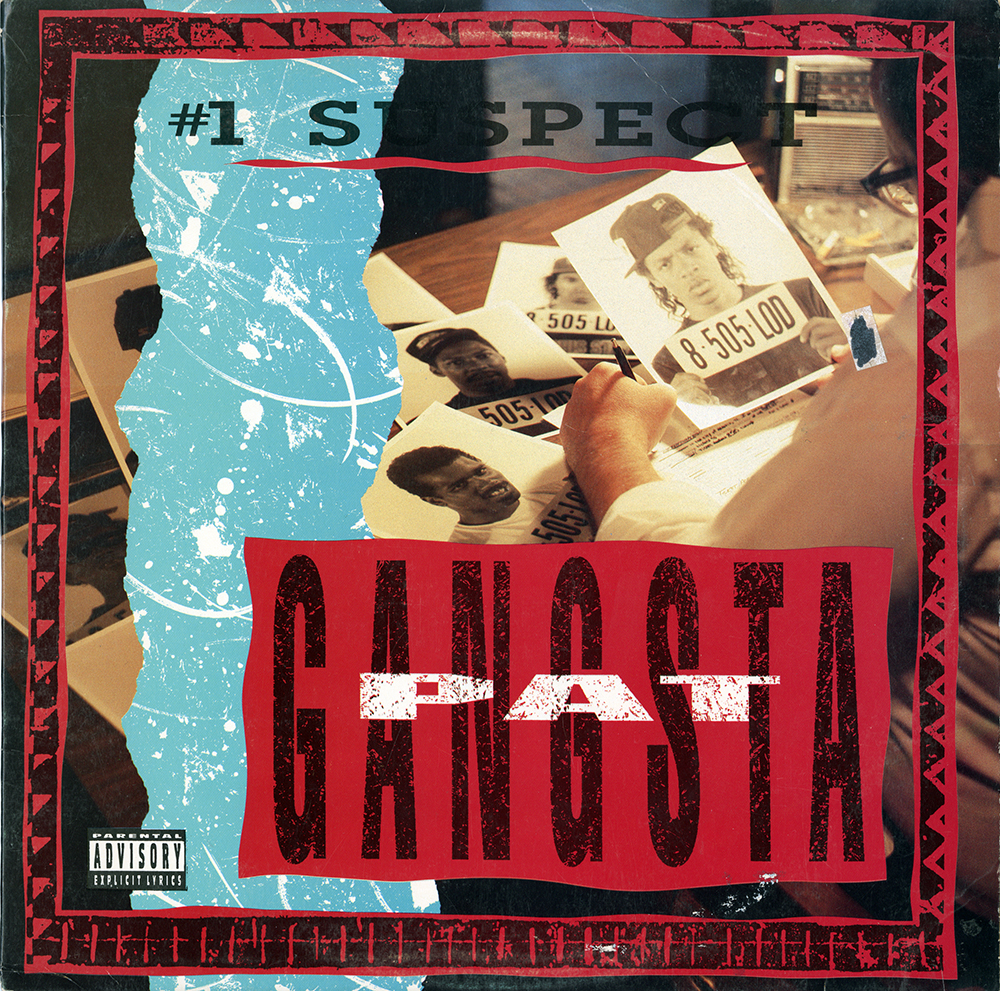

Much like Disco Hound had showed up to Memphis, trumpet in hand, with the hope that standing outside Stax Records might afford him an invitation inside, the young rap faithful arrived in throngs to Boyland’s OTS Records in Orange Mound to learn from one another. In the early 1990s, artists affiliated with and signed to the label included the likes of Radical T, Pretty Tony, 8Ball & MJG, and Psycho. However, its flagship artist was Patrick “Gangsta Pat” Hall, son of prolific soul drummer Willie Hall, who played with The Bar-Kays, The MG’s, and The Blues Brothers. Prior to Pat’s affiliation with OTS, he’d been primed by heavy-hitter Anthony Collier, a friend of Boyland’s, as the star of his own production house. Pat would achieve breakout success when he became the first Memphis rapper with a major label contract when Atlantic Records reissued his 1990 album #1 Suspect, a year after its original OTS release. Tragically, Collier died as an assailant shot into a vehicle at the corner of Danny Thomas Boulevard and Beale Street in May 1990, prior to Pat’s grand success. The shots rang out mere blocks from Memphis hip-hop mecca, Studio G, a club at 380 Beale Street. Boyland took up the mantle, steering Pat’s career, in the wake of Collier’s death.

For those artists, and numerous others looking for a safe haven, a youth center on Winchester Road near Tchulahoma named 21st Century aimed more specifically at providing rap hopefuls with a playground, of sorts, to hone their craft. Following its opening in 1989, an unwitting promoter named Larry Clark stepped forward to manage the venue while its owners filled it with performance and studio spaces. Among the most popular attractions at weekly talent shows were iterations of America’s Most Wanted and 2nd Level, a group including DJ Jus Borne, Cody Mack, and a soon-to-be standout Whitehaven rapper named Tela.

Clark, a die-hard Bar-Kays fan, got hip to the music promotion game after connecting with the legendary funk band’s bassist James Alexander, who in the 1980s enjoyed a second career pounding the pavement for several labels — his most steady work coming from Memphis’ Select-O-Hits. Working on projects with Alexander, Clark began carrying a camcorder to document the impact of their activations and promotional displays. The hobby evolved into a public access show for local Cablevision customers called UGTV, launched in the early ’90s. “It was the only game in town for rap music on TV,” Clark says.

“Everybody in the region would call me and ask, ‘How can I get on your show?’” he says, laughing. “I’d say, ‘Well, if you let me do your music video, I’ll play it on the show!’”

That proposition kept Clark a very busy man, as it did for Ralph McDaniels’ pioneering Video Music Box program on New York City’s public station WNYC-TV years earlier when hip-hop’s first music videos hit television airwaves.

“I knew how to walk right up to the edge without going over the edge,” Clark says. “I would do stuff that I knew I wasn’t supposed to be doing, like putting booty on TV. I’d go to the shake junt, turn the cameras on, film the girls shaking this and that. The folks at Cablevision would say, ‘We can’t show that!’ But I’d say, ‘It ain’t showin’ [that much].’”

Elsewhere in the land of broadcast media, a rivalry brewed between two jocks looking to earn their piece of the hip-hop spilling over from streets into the office parks that beamed music across the region. Returning to his former station in his hometown market, after a short tour away from Memphis radio, Downtown Jackson Brown stepped behind the microphone at Magic 101 in 1991 with one directive from his station owner: knock K97’s Stan Bell down a peg in the ratings.

Brown, psyching himself up for battle, egged on the station owner, throwing fuel on the matter.

“I told him, ‘Stan is killing everybody [in Memphis radio] at night, he’s talking about people, he’s degrading people, making ’em feel bad because he’s the king of the throne,’” Brown says. “‘In order to fight that, I need to be able to play a lot of Memphis records, because I got an ear to the street.’”

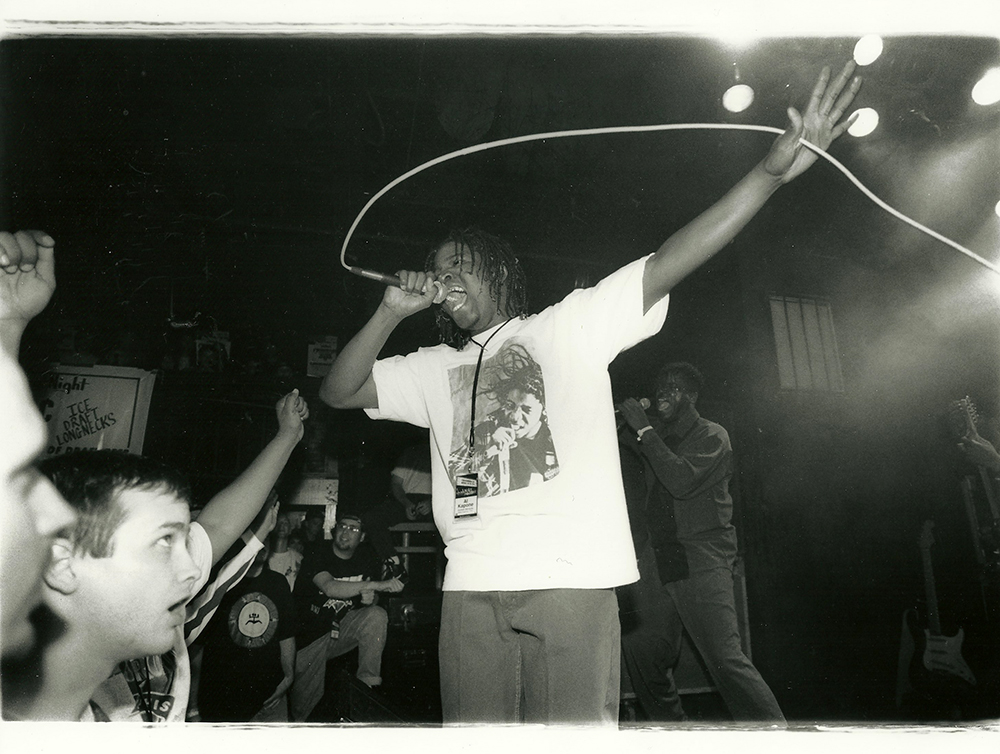

Brown’s station owner obliged. And Brown had his marching orders. He took to the clubs, often emceeing special events in and around Memphis to ingratiate himself with the underground.

“A lot of the club jocks at the time had mixtapes on cassette. You could get them volume by volume by different guys: DJ Spanish Fly, DJ Zirk, DJ Squeeky, and later DJ Paul and Juicy J,” Brown says. “I took stuff off the cassette tape like ‘Slob on My Knob,’ took it in the studio. We’d take a reel-to-reel machine, mark, splice, and flip the words out that we didn’t want to play on the radio. DJ Juicy J became bigger than life after that. I did the same with the bad language from DJ Paul’s ‘Where Is Da Bud?’”

“That rivalry made me better,” Stan Bell says. “It almost got personal, at one point, because we all want to be number one.”

Labeling them playfully as “radio wars,” Bell says, “We used to take shots at each other, saying things like, ‘The real hits are over here.’ It was fun. It was a friendly competition. But it was serious. And the ratings were good.”

Though he may not have had the green light to play some of the more suggestive street records creeping up from the Memphis underground, Bell did find a creative solution to crowdsourcing content directly from the Memphis streets. In the ’90s, he launched his signature segment “The Roll Call,” opening up the phone line for brave callers to freestyle about neighborhood news, shout out to local crews, and deliver dedications to their crushes. And he found an even more express route to Memphis’ youth: through the schools. In 1993, he returned to his alma mater, Northside High School, as an English teacher, breeding a captive audience and de facto street team within the student body.

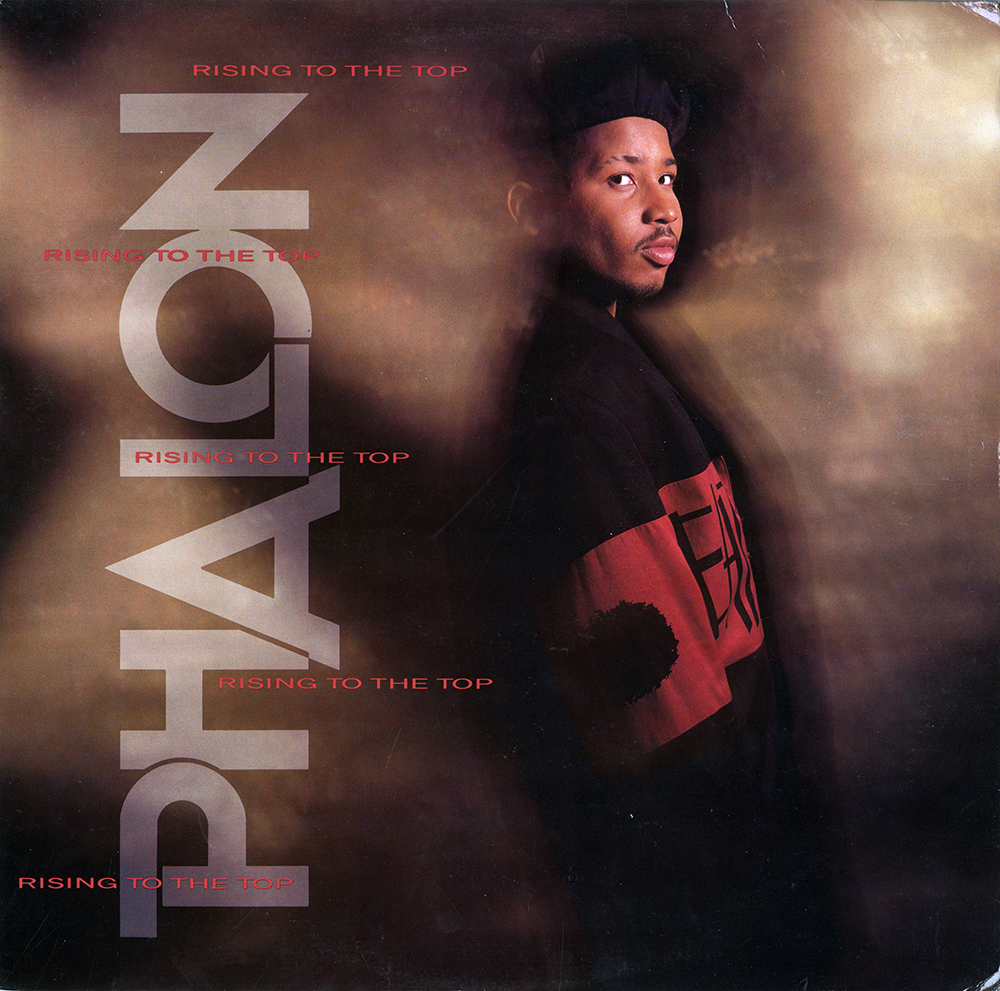

A similar exchange between generations facilitated a passing of the torch between multiple Memphis soul legends whose children and their friends made convenient use of the resources left intact by their elders. Like Willie Hall and Gangsta Pat, James Alexander’s son Phalon Alexander (later known as Jazze Pha) parlayed his charisma and father’s tenacity as a promotions professional into a release distributed by Elektra in the form of 1990’s Rising to the Top. Phalon regularly won talent shows in town with the help of a talented body-rocking sidekick named Act-A-Fool, who’d punch his ticket out of Memphis as a part of MC Hammer’s noodle-legged troupe of dancers. Thus was the link between Memphis’ burgeoning underground and the chart-topping pop-rap sensation.

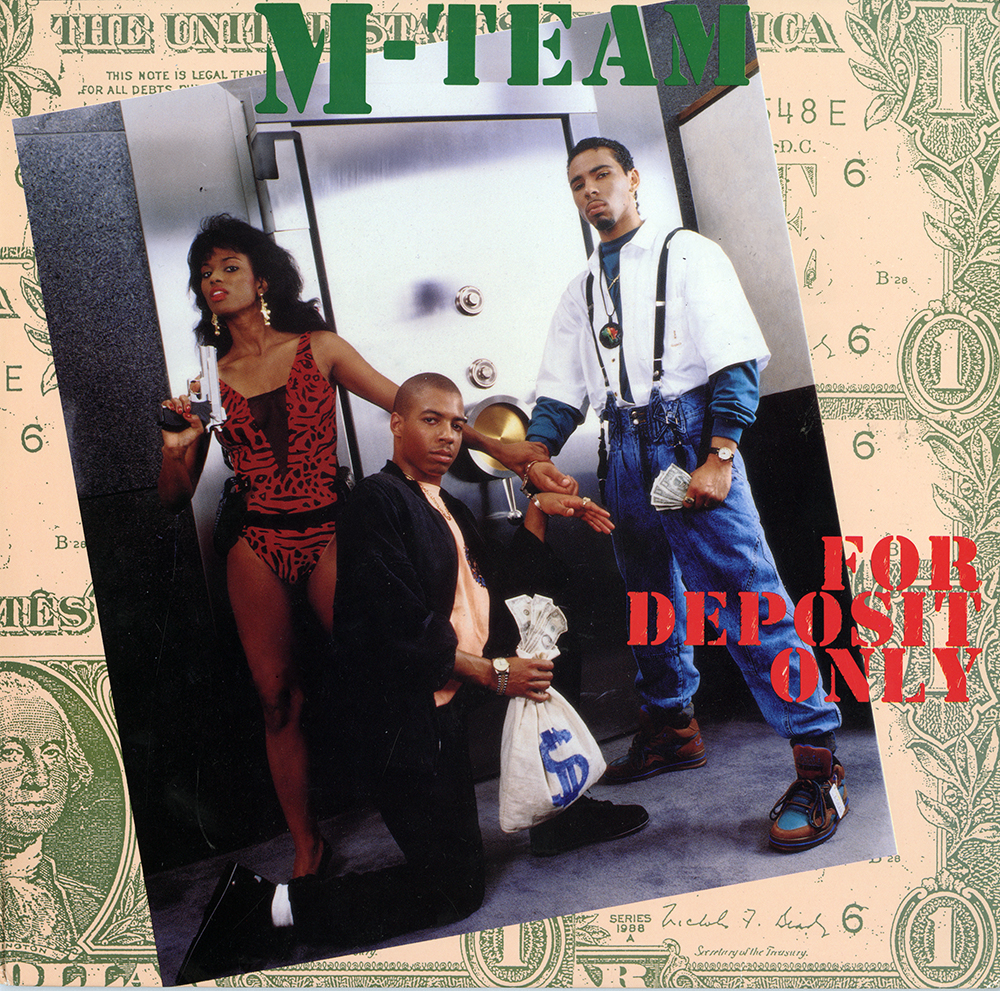

Around the corner from that South Memphis-based clique, brothers Archie “Baldhead” Mitchell and Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell carried on their family business, utilizing their grandfather’s Royal Studios to record their album For Deposit Only in the same facility where Al Green cemented hit-making status two decades prior.

“He was open all the way [to allowing hip-hop in his famed studio],” Archie says of his grandfather, Willie Mitchell. “He’d say, ‘Anything is worth a try. You never know until you do it.’”

Recorded together as M-Team, the brothers’ single “Rolling Samurai,” an ode to Suzuki SUVs, outfitted with custom speaker systems was met with a cease and desist from the Japanese automotive manufacturer.

“They told him they were gonna sue him if he put the record out because I was rapping about outrunning the police,” Boo laughs. “But that’s a joke because anyone with a Suzuki Samurai knows those jokers are slow as hell.”

Pop was like, “Well, we gotta put it out now!”

It was that level of support for his son’s newfound joy of music that found the elder Mitchell shopping his grandson’s tracks to labels in New York, one of which asked that they change the lyrics to their song “This Is Hip-Hop.”

“They were like, ‘You can’t say that,’ But what they were basically saying was, ‘Y’all are from the South, and this shit isn’t hip-hop.’”

With 50 years of hip-hop in the books, Memphis rappers routinely top the streaming charts, with Complex magazine regarding our city at No. 5 on their 2023 list of “The Best Rap Cities Right Now.”

Boo says this moment in time is “vindication.”

“From being one of the first Memphis rappers and the labels in New York to shun us, for us to be [what I consider] the No. 1 city in hip-hop right now, it feels good. I’m just proud of all the amazing artists who picked up where I left off and ran it up!”