The statue of a historic West Tennessean is planned to rise at the Tennessee State Capitol where the statue of another historic but controversial West Tennessean recently fell.

State lawmakers agreed to erect a statue of David Crockett on the capitol grounds in 2021. Public efforts to do this go back as early as 2012. The idea caught on but was tabled by the legislature in the 2020 session.

Since the approval of the legislation in 2021, the process has moved along slowly and quietly. The State Building Commission approved the project during its meeting earlier this month. Even that vote was wrapped in a procedure that needed no debate, only the approval of the commission’s staff, which it had. That vote, however, only allowed for the commission of an artist to design, fabricate, and install the monument.

Legislation in 2012 created the David Crockett Commission. That board’s job was to find the ways and means necessary to create a statue of Crockett on the capitol grounds. Commission members were not to be paid nor reimbursed for travel.

The group was also supposed to find private backers. The law reads, “No state funds shall [be] expended for such project.” That changed with the 2021 bill. Taxpayers will now foot the $1 million bill for the Crockett statue.

Another notable difference between the commission law and the new law is the location of the statue. Back in 2012, lawmakers just wanted it on the grounds of the capitol. But that changed in 2018, lawmakers had a more specific site for the statue: the pedestal above the Motlow Tunnel on Charlotte Avenue on the south steps of the Capitol Building.

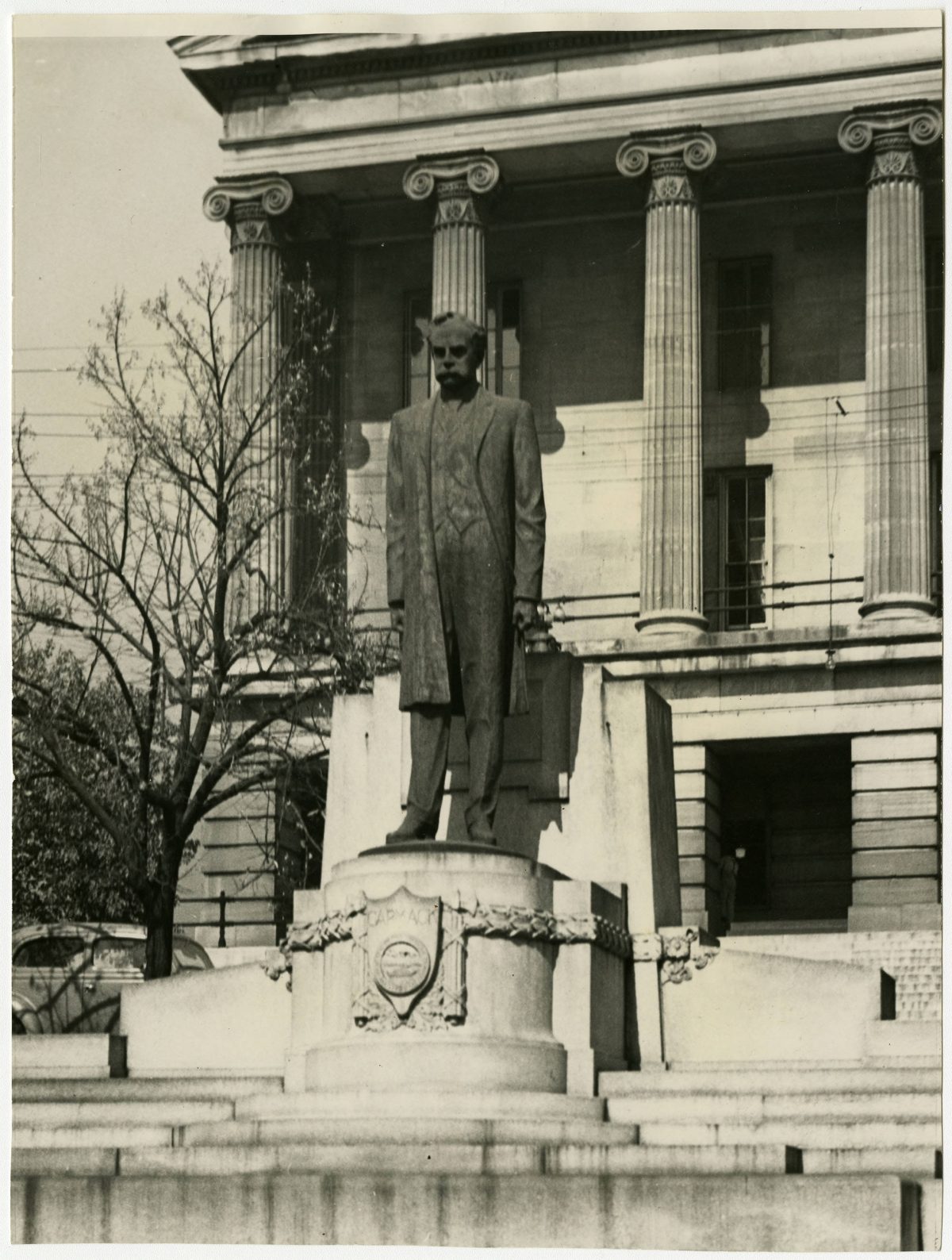

There was only one problem. When that legislation was introduced, another statue already sat at the location — the statue of racist, segregationist newspaper editor and politician Edward Carmack. The 2018 bill detailed the fact the Crockett statue was to be “in lieu of the Senator Edward Carmack statue” — that is, removing it and replacing it.

In his 1800s attire, curly, windswept hair and broad mustache, many who wandered by Carmack’s statue wondered aloud, “Why is there a statue of Mark Twain at the Tennessee capitol?”

But Carmack could not have been more different from Twain. For example, Carmack, as editor of the Memphis Commercial newspaper at the time, incited a mob against anti-lynching activist, journalist, editor, and business woman Ida B. Wells. The mob destroyed her newspaper office. She was away and stayed away, all according to the Tennessee State Museum.

Carmack was shot and killed by political rivals in Nashville, near where his statue was erected in 1927. It was installed, however, by a prohibition group (Carmack was also a staunch prohibitionist) that thought his big-profile death could further their cause.

With this, the GOP-led legislature must have faced a quandary in 2020 and 2021. How could they remove a huge historical marker from the capitol as they were fighting to keep so many others (like a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest)?

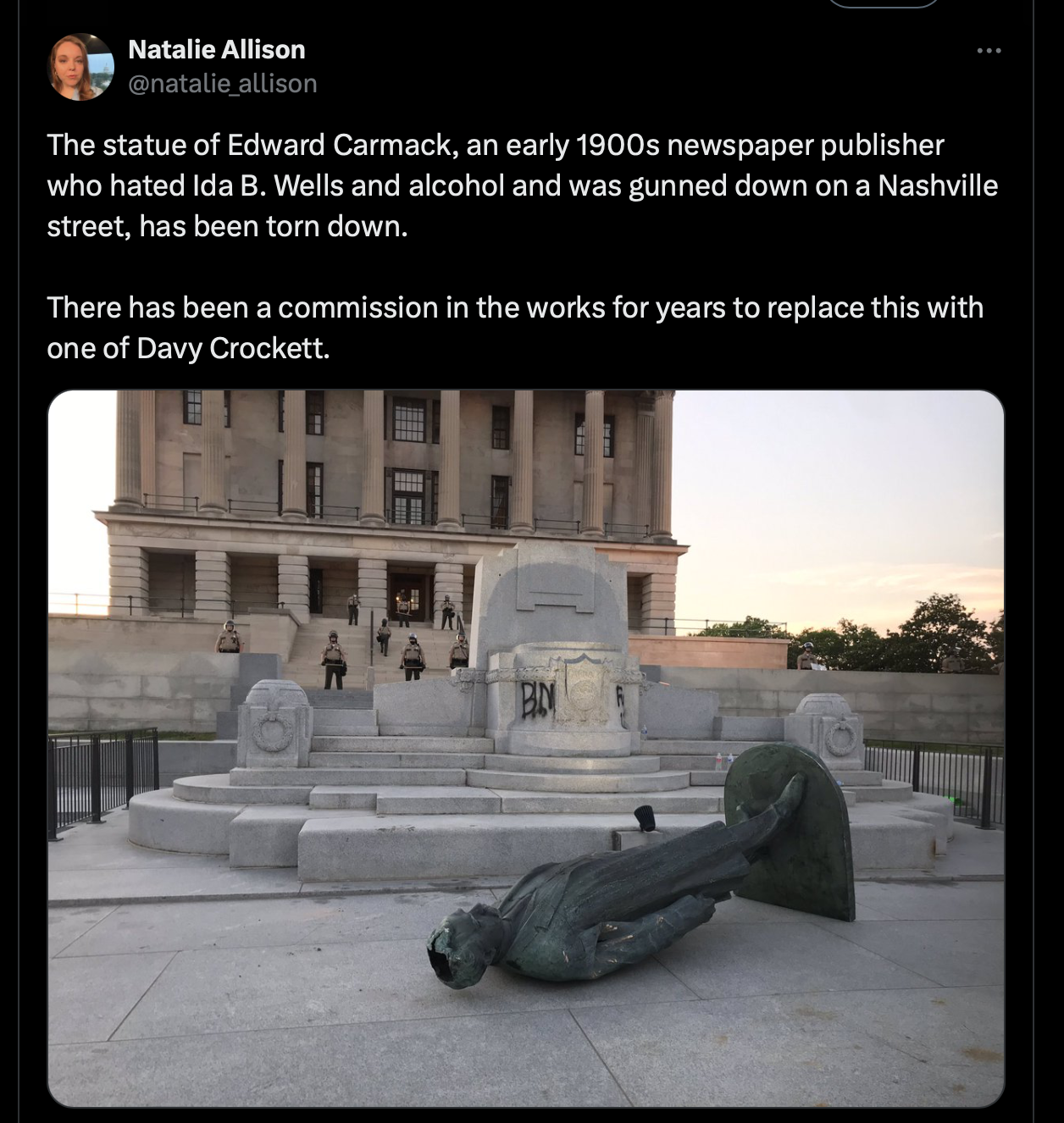

History, it seems, took care of that. Protestors tore down Carmack’s statue in 2020 during the turmoil following the police killing of George Floyd.

State officials said at the time the statue had been removed to another location. State law said it had to be replaced. But it’s unclear if it ever was.

But the suggestion that the statue had to be replaced by state law drew the (10-tweet) ire of pop star Taylor Swift.

“FYI, [Carmack] was a white supremacist newspaper editor who published pro-lynching editorials and incited the arson of the office of Ida B. Wells (who actually deserves a hero’s statue for her pioneering work in journalism and civil rights),” Swift tweeted at the time. “Replacing his statue is a waste of state funds and a waste of an opportunity to do the right thing.”

One of the 2021 bill’s sponsor, Sen. Steve Southerland (R-Morristown), even told The Chattanooga Times Free Press at the time, he “didn’t think it would be possible to remove Carmack.”

The newspaper story said, Southerland “then smiled and then added: ‘Someone removed it for us, so they did us a favor.’”

Maya Smith

Maya Smith