In this year dedicated to celebrating the 50th anniversary of Stax Records, the hits just keep on coming, with the latest batch of Stax product: independently packaged DVDs, two released this week, one released in late September.

Co-directed by local filmmaker/writer Robert Gordon and his partner Morgan Neville, the two-hour documentary Respect Yourself was broadcast this summer as part of PBS’ Great Performances series, but an expanded version was released on DVD October 2nd.

Consisting of interviews — both new and archival — with most of the key players, including a rare contribution from Stax founder Jim Stewart, Respect Yourself gives a chronological telling of the Stax story that mostly hits the obvious high (and low) points.

For those who know the music and the story behind it, much of Respect Yourself may feel like rehash. It is a primer, but with so much attention given to Stax locally this year, it’s easy to forget that most people — most music fans, even most Memphians — still aren’t that familiar with the details of Stax. And Respect Yourself reinforces what an amazing story it is: an artistic entity whose very success was rooted in racial partnership and shared/mixed culture in the middle of the civil-rights-era South; a record label whose thrilling music embodied — like perhaps no other cultural product of the time — the hope and ultimately broken promise of racial integration in the ’60s and ’70s. This story can’t be told enough, and Respect Yourself tells it well.

Early on, tireless label booster Deanie Parker allows that “Stax Records was an accident,” pointing out that siblings Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton never intended to start an R&B record label when they opened a recording studio in a converted theater on McLemore Avenue. The implication is that Stax was ultimately the product of the neighborhood it became a part of.

In terms of reviewing the basic spine of the Stax story, Respect Yourself offers a neat, multi-viewpoint retelling of the Otis Redding origin story — that day Redding showed up as another artist’s “valet” and pestered his way to the microphone — with Booker T. Jones speaking eloquently about knowing he was part of something special and staying in the moment.

There’s also a great segment on the Stax family’s visit to the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, with Memphis Horn Wayne Jackson talking about the culture clash between the long-haired, unkempt hippie crowd and the relatively clean-cut Stax crew, who showed up with matching suits and dance steps: “We must have looked like a lounge act or something. But it killed ’em. And when Otis walked out onstage, it was over for everybody.”

Those good times wouldn’t last, and Respect Yourself deftly shows how the tragic four-month stretch between December 1967 (when Redding died in a plane crash) and April 1968 (when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis) transformed the label.

There are also less obvious pleasures and insights in the film. During one interview segment, Jones sits at his organ and replicates the sax riff that, as a teenager, he played on the early Stax hit “Cause I Love You,” a duet between Rufus Thomas and his daughter Carla. Similarly, there’s a graceful moment when, during a newly filmed segment, William Bell stands in front of a piano manned by Marvell Thomas and sings his Stax standard “You Don’t Miss Your Water.” These dynamic segments are so good, you wonder why there aren’t more like it.

And even those who think they’re pretty familiar with the Stax story may learn a few things: the extent to which the Lorraine Motel was used as a second home — for both work and play — for Stax artists (reflected, in part, by a vibrant color photo of Carla Thomas emerging from the Lorraine pool); the revelation that the label’s iconic finger-snap logo was the brainchild of later-period executive Al Bell and thus post-dates most of the classic music it’s associated with; the level of violence that infected the label in the aftermath of the King assassination.

But as fine as Respect Yourself is, most established Stax fans will crave more depth, and the two other recent label-specific DVD releases provide it. Released concurrently with Respect Yourself is The Stax/Volt Revue Live in Norway, 1967, which captures one set on the fabled Stax European tour. Filmed in black and white, this 75-minute concert features performances from Booker T. & the MGs, the Mar-Keys, non-Stax performer Arthur Conley, Eddie Floyd, Sam & Dave, and Otis Redding.

This is a more subdued affair than you might expect, with an extended Conley performance of his hit “Sweet Soul Music,” in particular, coming across as filler. But just having sustained footage of Sam & Dave performing is a revelation, even if the material here isn’t as exciting as the concert footage featured on Respect Yourself. Certainly, the footage reinforces the degree to which Sam Moore outshines Dave Prater vocally. And Redding, closing the show with “Try a Little Tenderness,” towers over them all.

For more Redding, check out the hour-and-a-half-long documentary Dreams To Remember: The Legacy of Otis Redding, which was released on September 18th and, for serious Stax fans, is the most interesting DVD in this current batch.

Though the interview subjects are oddly limited — Steve Cropper, Wayne Jackson, Jim Stewart, and Redding’s widow, Zelma, mainly — Dreams To Remember offers the depth that Respect Yourself — charged with covering an entire label rather than just one artist — can’t match.

Because Cropper co-wrote so many songs with Redding (in addition to working on the recording sessions themselves) and because Jackson, as a trumpet player, was uniquely attuned to Redding’s musical instincts, these men are positioned to offer considerable insight into Redding’s music. And they do not disappoint.

Cropper talks about coming up with the idea for “Mr. Pitiful” after hearing WDIA disc jockey Moohah Williams tab Redding with that moniker for his begging, pleading vocal phrasing. Cropper tells of how Redding took Cropper’s song concept and immediately worked out the song’s chorus.

For “I Can’t Turn You Loose,” Cropper reveals that there wasn’t time before the session to write multiple verses, so Redding kept repeating himself to keep up with the energy of the song, resulting in a recording that functions like the classic Stax instrumentals.

Cropper also talks about how his guitar playing for Redding, in particular, was rooted in country music and how Stax liked to try and reinvent songs they covered, turning ballads into fast songs and fast songs into ballads, or writing new intros and outros unconnected to the original songs.

The most famous example of this was Redding’s take on the standard “Try a Little Tenderness,” which Stewart dubs the best record Stax ever made. Cropper talks about how drummer Al Jackson’s double-click beat with his drum sticks and Cropper’s own Latin-style guitar lick create a “Drifters kind of groove” before Redding carries the song away into something else altogether.

“Nobody will ever sing ‘Try a Little Tenderness’ the way Otis Redding sang it,” Cropper says.

The most interesting area of this technical talk comes in a discussion on the horn work on Redding’s records. Jackson gives a colorful explanation of how Redding would gather his horn players together and instruct them on what to play by singing the various horn parts.

This dynamic was made explicit on “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa,” which Cropper says he and Redding wrote at a Memphis Holiday Inn on Third Street. (Because of Redding’s touring schedule and because he didn’t live in Memphis, he was only available to Stax two to three days out of a three-month period, according to Cropper, which made for some intense, prolific writing and recording sessions.) The nonsense syllables that make up the song’s title (and chorus) were Cropper’s interpretation of the saxophone sound Redding would make when arranging horn parts.

“When I wrote with Otis, I wrote about Otis,” Cropper says, before launching into song himself: “I keep singing these sad, sad songs/Sad songs is all I know.”

The relationship between Redding and his horn section that “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa” takes as its subject is given visual accompaniment here in a splendid bit of black-and-white footage (also seen on Respect Yourself ) where Redding sings the song, sitting down, with his horn section around him. This performance literalizes the call-and-response quality between Redding and the horn section, Redding turning to Jackson or one of the other players after the chorus with a generous offer of “your turn.”

Stewart ties this all together with an insight about the absence of back-up singers on Redding’s recordings. Stewart points out that Redding used his horn sections as a stand-in for what back-up vocalists would be for other artists.

This performance footage isn’t exactly real, however. It seems to be lip-synched, which is the case with many of the television performances shown on Dreams To Remember. Zelma Redding talks about how much her husband struggled with these lip-synched performances, because he rarely sang his songs the same way and often forgot the exact lyrics on the recordings. “I look at some of the footage and say, Lord have mercy,” Zelma says.

In addition to this insight, Dreams To Remember is packed with plenty of standout footage, including a goofy promotional video for the duet single “Tramp,” with Redding wearing overalls and riding a donkey around a farm to play up the “country” character he plays on the song.

Concert footage includes an awesome rendition of Sam Cooke’s “Shake” at Monterey and, most poignantly, a performance of “Try a Little Tenderness” on Cleveland television the day before Redding’s death. Unlike the other television appearances, this one is live, as is clear when Redding ad-libs the phrase “mini-skirt dress” in the opening lines.

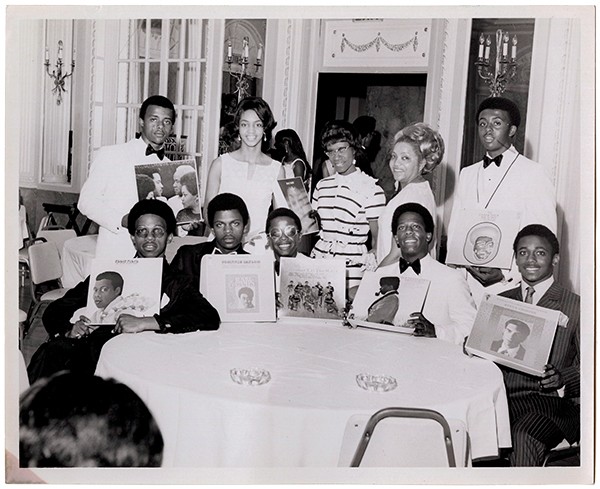

Courtesy Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Courtesy Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Wayne Moore, photographer; Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Wayne Moore, photographer; Stax Museum of American Soul Music

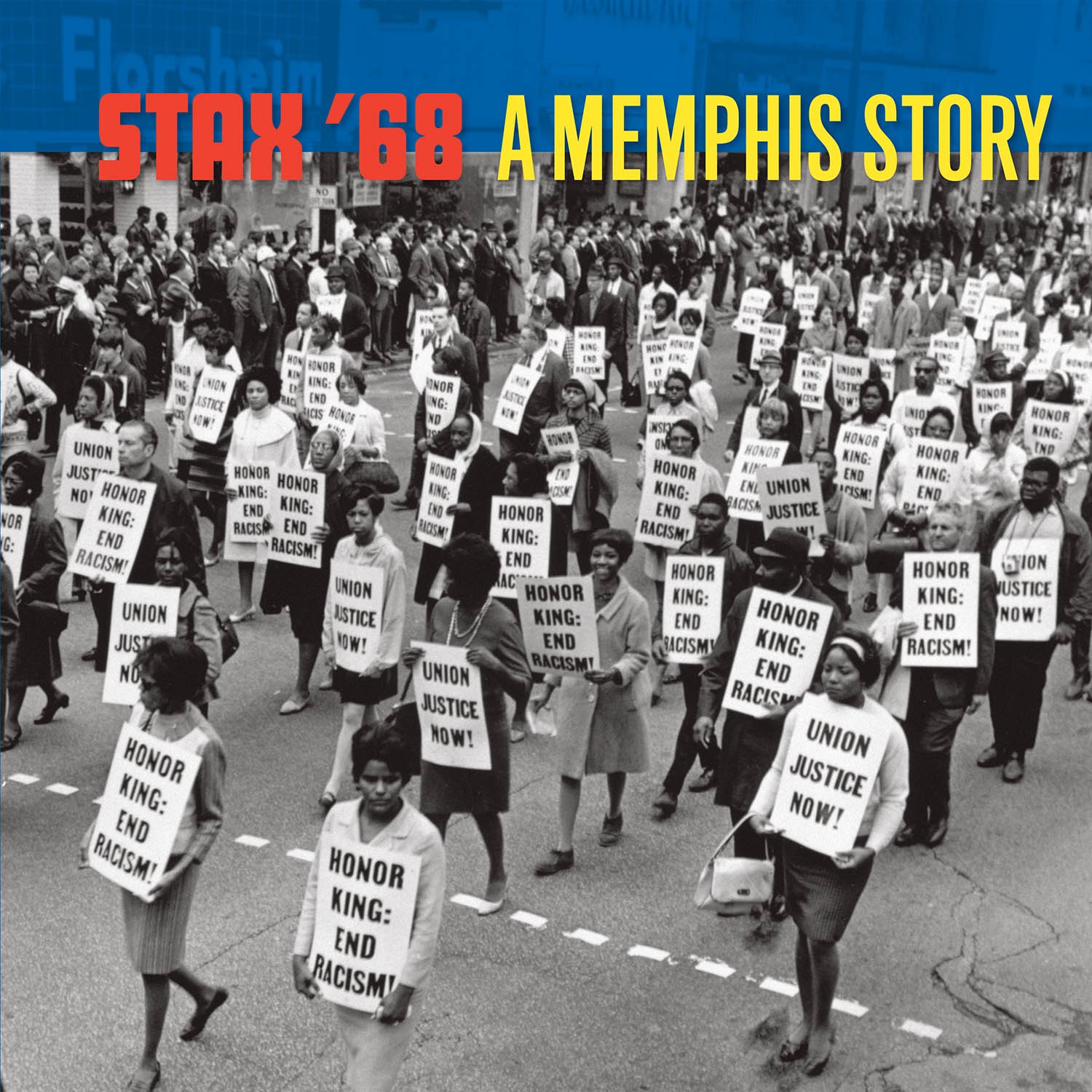

Alan Copeland

Alan Copeland  Ronnie Booze

Ronnie Booze  Focht

Focht  Alex Burden

Alex Burden

Courtesy EMI Records

Courtesy EMI Records