This is our year of musical remembrance. Stax is 50. The King’s been gone for 30 years. Forty years ago this December, Otis Redding and four harmonious young Memphians known as the Bar-Kays died in a plane crash.

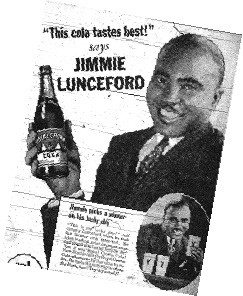

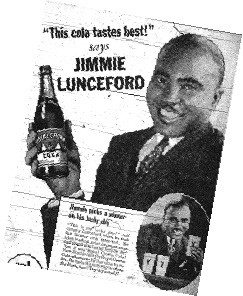

This year also marks an anniversary for another giant of our city’s musical past — one that won’t draw legions of shrine-building visitors to Memphis or inspire reunion concerts or documentary films. Sixty years ago on July 12th, the swing orchestra leader Jimmie Lunceford died — either by a heart attack or poisoning depending on whom you believe — while signing autographs in a record store on a tour stop in Seaside, Oregon.

Despite the lack of recognition in the City of Good Abode, Jimmie Lunceford represents a legacy that has meant as much to Memphis music as more recent and celebrated figures. The man who once beat Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Fletcher Henderson, and others in a battle of the big bands now lies buried, mostly forgotten, in Elmwood Cemetery.

It can be difficult to quantify the success of an artist who died before Billboard charts began to define musical success. Sheet music outsold records for most of Lunceford’s career, spanning 1930-1947, and a musician made a name and a living on the road then.

“Lunceford had the best of all bands”

Lunceford’s peers and competitors, however, knew what they were up against. No less an authority than Glenn Miller — himself leader of a top-shelf swing outfit until his plane vanished crossing the Atlantic during WWII — summed it up: “Jimmie Lunceford has the best of all bands. Duke [Ellington] is great, [Count] Basie is remarkable, but Lunceford tops them both.”

He spent barely three years of his life here, from 1927 to 1930, but began a tradition of public school music education that pipelined talent to the Memphis scene for generations to come. Not only is Lunceford overlooked in our storied history, his legacy of education is absent from the civic discussion surrounding the revival of our once vital music industry.

“He had a very good effect on the students here”

The Memphis City Schools have churned out professional musicians like Penn State has linebackers. Players diverse in style and age, like former Ray Charles Orchestra music director Hank Crawford and renowned jazzmen Phineas Newborn Sr., his sons Calvin and Phineas Jr., cerebral horn-blowers Charles Lloyd and Frank Strozier, and soul men Booker T. Jones, Isaac Hayes, David Porter, the Bar-Kays, Earth, Wind and Fire vocalist Maurice White, and members of the vaunted Hi Rhythm section, among dozens of others, all came through Memphis public school music programs.

This legacy, unparalleled in any urban school system nationally, began in 1927 when Lunceford landed at Manassas High School, fresh from Fisk University in Nashville.

Ninety-two-year-old classical pianist Kathryn Perry Thomas — one of three living graduates of Manassas’ class of 1932 — is the last surviving Memphian to have played music with Lunceford. She recalls Lunceford’s presence on campus. “I was going to school when he was there,” she says. “He had a very good effect on the students there. He taught football, baseball, and music.”

The first Memphis city school orchestra

Orchestra leader Jimmie Lunceford

Lunceford had no budget for a music program. In fact, he wasn’t hired as a music teacher at all, but instead as an instructor of English and Spanish and coach of the Manassas football and baseball teams. The school had no instruments, no music curriculum, no idea what music education could do for the community. But like the football coach that he was, Lunceford brought a group of young men together, motivated them, equipped them — with help from community donors — and refined them as a unit. He named them like a football team too, drawing on local history: the Chickasaw Syncopators.

“Manassas had the first orchestra of any school in the city with Mr. Lunceford,” Thomas says. “He was a good disciplinarian, a good teacher, and the students just had a fit over him. Lunceford played sophisticated jazz. I used to practice with them.”

The Chickasaws included drummer Jimmy Crawford and bassist Moses Allen, Manassas students who continued playing with Lunceford’s orchestra longer than any other players. Two of Lunceford’s Fisk pals, pianist Ed Wilcox and saxophonist Willie Smith, also had joined up by 1928. These four comprised the nucleus of the Lunceford band through the early 1940s.

The orchestra had come to the attention of the press by early 1930. The Chicago Defender, a national African-American newspaper, wrote that Lunceford’s 11-piece band included musicians who sang and doubled on different instruments.

Chickasaws define new sound

The Chickasaws recorded a two-sider on their leader’s 28th birthday, June 6, 1930, at the Memphis and Shelby County Civic Auditorium (then located at Main and Poplar) for Victor Recording Company. Allen, the band’s bass player, preached with tongue firmly planted in cheek through “In Dat Mornin’.”

He goaded the trumpet solo:

“Oh, Gabriel, I want you to go down this mornin’, I want you to place one foot on the land and the other foot on the sea; I want you to blow that silver trumpet calm and easy … I imagine I can see him bust the bell of that trumpet wide open.”

The flipside, “Sweet Rhythm,” could have served as the Lunceford anthem, in both name and sound. (These early recordings can be heard at http://www.redhotjazz.com/chickasaw.html.)

The Lunceford sound distinguished itself in a crowded field of talented swing bands with its two-beat syncopation, a sonic ancestor of what came to be known as the “Memphis sound” heard in the 1960s and 1970s in Stax Records’ trademark echophonic rhythm and in the laid-back Willie Mitchell groove of Hi Records. Bertil Lyttkens Collection

Bertil Lyttkens Collection

Musicians Ed Wilcox, Jimmy Crawford, Moses Allen, and Al Norris, left to right, at the Cotton Club in Harlem in 1934

“When he left Manassas, those who had finished went with him. He became famous with that orchestra,” Thomas recalls.

More importantly for the city, orchestras became standard in public schools. Manassas hired a replacement for a position that hadn’t existed previously: band director.

Lunceford’s band officially turned pro in late 1930 and hit the road, changing their name to the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra because the Chickasaw Syncopators didn’t resonate with national audiences.

“Rhythm Is Our Business”

Though the band would gradually grow to 18 musicians at the time of Lunceford’s death, their double-duty as players and entertainers distinguished the orchestra throughout its existence. Lunceford biographer Eddy Determeyer states that the orchestra “pioneered the use of choreography in black music.”

Jack Bradley Collection

Jack Bradley Collection

On stage, members of the Lunceford orchestra tossed their instruments in the air in unison, danced and sang interchangeably, as the leader — decked in white tails and his glowing grin — conducted. Their uptown vocals can be heard on recordings like “My Blue Heaven” and “Rhythm Is Our Business,” a Lunceford composition that later served as the title of his biography.

Between 1930 and 1947, Lunceford’s group challenged the giants of jazz, Ellington and Basie, for orchestral supremacy. They drew raves for their showmanship and instrumental ensemble work and returned to Memphis for one-nighters at Beale Avenue Auditorium at Church Park. Lunceford remained friendly with Memphis, wooing Crystal Tulli, a teacher at Booker T. Washington High School whom Lunceford had met at Fisk. They married in 1934, the year of Lunceford’s arrival at Harlem’s Cotton Club, known then as the greatest nightclub in the world.

Renewing personal remembrances

Local appearances stirred up the Bluff City. The African-American Memphis World newspaper reported that tickets to Lunceford’s August 1944 show sold out in hours. Visits usually included a reception at the home of a prominent citizen. One concert preview said that Lunceford looked forward to “renew[ing] personal remembrances.”

Among those remembrances renewed were the students at Manassas. “He would come over to the school each and every time he would play Memphis,” recalls Emerson Able Jr., who took Lunceford’s old job as Manassas band director in 1956. “His band would perform for the [Manassas] student body, and our band, the Little Rhythm Bombers, would play for him. This is where most of us, as students, saw him. He would bring the big band over to Manassas and perform.”

Forgetting Jimmie

Memphis music, if you believe what you read, is a story of iconoclasts, renegades, and visionaries whose disdain for rules and conformity forged original sounds. Lunceford doesn’t fit into the pantheon of gritty working-class heroes who embody the Memphis sound, though. The big-band Lunceford sound required discipline, education, polish, and a collective approach to performance. For this reason, it seems, he’s been overlooked in Memphis music history.

In Goin’ Back to Memphis, James Dickerson wrote of the period Lunceford spent in the city, “Throughout the twenties, Memphis music underwent significant changes. The sophisticated blues of the teens … were replaced on Beale Street by its long-neglected country cousin, the down-home blues.”

Lunceford bucked the more celebrated trend of unsophisticated down-home blues in Memphis, as he groomed a group of city school kids into a jazz orchestra later noted for its precision and technical ensemble work.

Dickerson suggests that the bandleader’s urbanity sacrificed his soul: “I am sure black activists would today consider Lunceford an Uncle Tom. He led his orchestra with a long, white baton and dressed elegantly but I don’t think he was being accommodating to white society so much as living out a fantasy of how society should conduct itself. Considering his disdain for any deviation from his strict Protestant behavior, it is not surprising Lunceford left Memphis at the first opportunity.”

Dickerson offers no facts upon which to base any of these observations, including the false understanding of Memphis as a city without religion. Nor does he account for Lunceford’s choice to be buried in a city the bandleader supposedly couldn’t wait to leave. Ultimately, Dickerson prefers to tell the Memphis music story in a way that doesn’t grasp the complete picture.

Similarly, the over-quoted music producer Jim Dickinson explains the upward thrust of Memphis music history in terms of “racial collision.” Robert Gordon wrote in the influential It Came From Memphis, “The forces of cultural collision struck thrice in the Memphis area, first with the Delta blues, then with Sun [Records], then with Stax,” thus excluding Lunceford, who was no Delta bluesman and had died before Sun or Stax came into being, from the discussion.

“My Blue Heaven”

Today, barely a trace of Lunceford remains in the city. Imagine the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown without Willie Mays or the courtyard of Graumann’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood without the imprints of Jimmy Durante’s nose or Marilyn Monroe’s hands. Our own walk of fame down on Beale Street feels just as empty thanks to the omission of Lunceford.

A historical marker in front of Manassas High School commemorates alumnus Isaac Hayes, but there’s no public display of affection for Lunceford, the onetime king of swing.

Finally, locals trying to learn about the life of Lunceford would be hard-pressed: The acclaimed biography Rhythm Is Our Business isn’t available at local bookstores or any public or college library.

Coda

Jimmie Lunceford, a healthy, teetotaling, non-smoker, dropped dead at a personal appearance in Seaside, Oregon, on July 12, 1947. The official cause of death was a heart attack, though his bandmembers claimed that the owner of the café where the band lunched had taken exception to serving the group of African Americans. Several of them complained of illness after their lunch and speculated that they had been poisoned.

Lunceford’s Memphis funeral procession traveled up Wellington Street (now Danny Thomas Boulevard) to Mississippi Boulevard. You could have seen it pass from the front porch of Lunceford’s last Memphis residence at 678 E. Iowa Avenue (now E.H. Crump Boulevard), as it crossed that street and turned up Walker toward Elmwood Cemetery. Fans lined the streets along the route.

After a star-studded New York funeral service attended by top black entertainers Pearl Bailey, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Noble Sissle, the Memphis ceremony brought out his inner circle. Fisk classmates served as pallbearers, while Lunceford’s father, brothers, widow, and in-laws stood out among the reported thousands who stacked the mahogany casket with flowers.

Nationally syndicated columnist Nat D. Williams, himself an educator in the Memphis City Schools at Booker T. Washington High, eulogized Lunceford in his weekly “Down on Beale Avenue” column, offering still poignant views on the man’s meaning to Memphis:

“Jimmy Lunceford was buried here in Memphis. The spot he occupies should have something of a special significance. … He took a group of relatively unsophisticated Memphis colored boys and welded them into an organization which scaled the heights of musical eminence. … He presented something new in the way of musical presentations by Negro orchestras.”

Williams praised Lunceford’s commitment to his race. While other great African Americans abandoned their people, so Williams wrote, “Lunceford and many others like him chose to remain at home, and with their people. [His death] should have meaning in inspiration and guidance to others. If we permit it, Lunceford’s burial in Memphis can mean this.”

Very special thanks to Eddy Determeyer, author of the Lunceford biography Rhythm Is Our Business, who supplied key facts and photographs for this story.

Bertil Lyttkens Collection

Bertil Lyttkens Collection  Jack Bradley Collection

Jack Bradley Collection

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks