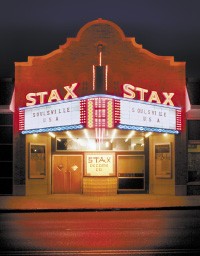

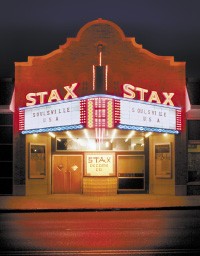

Fifty years ago, white Memphis fiddle player Jim Stewart started a music label, called Satellite, releasing a few pop, rockabilly, and country singles. A few years later, that label, rechristened Stax, would emerge as the Southern giant of soul music, rivaling its Detroit counterpart Motown as the country’s most important purveyor of “black” pop music (not such a simple distinction at Stax).

This year, three organizations — Soulsville (which operates the Stax Museum of American Soul Music and the Stax Music Academy on the original label site at the corner of College and McLemore in South Memphis), the Memphis Convention and Visitors Bureau (MCVB), and Concord Music Group — have joined forces to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Stax with a yearlong campaign that will involve a massive slate of classic Stax reissues, a publicity campaign, a new documentary about the label, a series of revue-style concerts (including June 22nd at the Orpheum), and, most daringly, a relaunch of Stax as an active record label.

According to Deanie Parker — a former Stax publicist, songwriter, and artist who would go on to head up the Soulsville organization and is spending her final year on the organization’s board overseeing the “Stax 50” celebration — the genesis of this celebration came a few years ago, right after the museum opened in 2003 and Soulsville board members were looking toward the future: “While we were concentrating on the stabilization of Soulsville — the academy and the museum — we were also thinking, What is the next thing that warrants our time and attention? And one of the things the board had put on its agenda was Stax 50.”

Under Parker’s direction, Soulsville partnered with the MCVB, which had overseen the city’s “50 Years of Rock and Roll” celebration in 2004. But what could have been — like the “50 Years of Rock and Roll” campaign — a primarily Memphis-generated P.R. initiative became something more tangible when the California-based Concord Music Group came into the mix.

Concord purchased Fantasy, which had acquired the bulk of the Stax catalog (that not distributed by Atlantic records during the early years of the Memphis label’s history) and the Stax name after the soul label’s messy mid-’70s dissolution, in 2004, with plans to re-energize the Stax brand.

“In the purchase of Fantasy, everyone thought that Stax was a very important part of the package,” says Robert Smith, senior vice president of strategic marketing for Concord. “Those Stax records, obviously, never went away, but it was certainly looked at as a property where the catalog could be further revitalized and the label could be relaunched. It’s one of those very few actual brands in music. So the plan was never just to do more reissues and raise awareness about the legacy but also to move forward and relaunch it as an active soul-music label.”

Smith says that the 50th anniversary of the label was a definite factor in Concord’s initial planning, making a partnership with Soulsville and the MCVB a mutually beneficial relationship.

“We found within the Concord family, I think, an appreciation for and a sincerity about the Stax catalog,” Parker says. “And one of things that I like about Concord is that they do have marketing and promotional savvy. They’ve got that. They’ve got the capacity and creativity to recognize promotional opportunities, seize them, and take them to the next level. And [we’ve] not had that opportunity with the previous owner of the Stax catalog.”

Parker praises Fantasy as a respectful guardian of the Stax catalog, but says that now “the need is different.”

Concord’s revitalization of Stax began earlier this year with what promises to be a massive reissue campaign. The first foray came in February with Johnnie Taylor: Live at the Summit Club, a concert album from the Stax singer (best known for his 1968 hit “Who’s Making Love”) recorded in Los Angeles during the filming of the famous 1972 WattStax concert. Concord followed in March with the two-disc Stax 50th Anniversary Celebration, the first self-contained collection to span the gamut of Stax’s history, and a bonus-track-laden reissue of Carla Thomas’ 1967 studio album The Queen Alone.

The reissues will continue with a series of “very best of” collections from multiple Stax artists, expanded reissues of Isaac Hayes’ studio albums, multi-disc sets dedicated to the Staple Singers and the 1967 Stax/Volt Revue European tour, and other releases.

A Stax documentary — Respect Yourself: The Stax Records Story — produced and directed by Memphian Robert Gordon and Los Angeles filmmaker Morgan Neville will be released on DVD by Concord in August, following a broadcast as part of PBS’ Great Performances series.

Many of these releases require cooperation between Concord and Rhino, which holds the rights to the portion of the Stax catalog retained by Atlantic after that label’s distribution deal with Stax ended in 1968.

“Traditionally, over the years, there has been a great deal of cross-licensing between Atlantic, now Rhino, and Stax, so that’s just continued,” says Smith. “If you go through your Stax  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

collections, there is a great deal of intermingling. Stax 50th is clearly a major piece of collaboration. Twenty-one [songs] from Atlantic and 29, I think, from our Stax catalog.”

The Stax 50th compilation was produced and compiled by noted Stax scholar Rob Bowman and Cheryl Pawelski, a Concord executive who left the company in January to take the job of vice president of A&R at Rhino, a move that Parker hopes will help bring the two sides of the Stax legacy even more in line.

“Without a total understanding of how all of that fits together, and realizing that whatever they’ve structured today is going to change tomorrow, because the industry is in flux, I will say this with total confidence: That woman loves the Stax product and the soul music that comes out of Memphis,” Parker says. “So we have an ally. We have somebody there who understands and appreciates it enough that when she has to go to a meeting where there are 20- and 30-year-olds making a decision and who can only relate to rap and hip-hop, she’ll bring some balance to the table. Makes a difference.”

But as exciting as the current (and future) reissue campaigns might be to fans of Stax’s classic sound, Smith emphasizes that that’s only a part of what Concord has planned for Stax.

“The real purpose is to combine the heritage and legacy of Stax with the relaunch of the label and the signing of new artists and releasing of new records,” Smith says. “If you’re only dealing with it from a catalog standpoint, then you’re really missing what is truly behind this, which is that soul music is truly an important part of American musical culture.”

This relaunch of Stax as an active label began modestly with the March release of Interpretations: Celebrating the Music of Earth, Wind & Fire, a tribute album to the ’70s Chicago funk/R&B band — founded by Memphian Maurice White — in which contemporary soul artists cover the band’s songs.

This relaunch kicks into a higher gear in August with a new release by highly regarded neo-soul singer Angie Stone, followed by albums from Lalah Hathaway (daughter of soul star Donnie Hathaway), N’Dambi, and Soullive. But the highest-profile release on the new Stax will likely come from a name inseparable from the old Stax: Isaac Hayes, whose first album of new material under the Stax name in 20 years is set for release later this year.

John Burk, Concord’s executive vice president of A&R, acknowledges that it was important for Concord to launch this new Stax with a connection to the label’s legacy, but Smith says the signing of Hayes goes far beyond mere symbolism.

“Isaac Hayes is still a really vital artist and still a really important one, and we’re very fortunate to have him recording for Stax,” Smith says. “It wasn’t done for another reason. He’s just a great artist and one who does stand for what Stax is about, so of course it’s important from that standpoint. But Isaac Hayes is not recording here because he was on Stax. He’s recording here because he’s Isaac Hayes.”

Concord hopes to expand interest in a classic artist with the Hayes release, something the label, which released the hugely successful 2004 Ray Charles album Genius Loves Company, has some experience in.

“There are a lot of reasons it would be satisfying,” Smith says. “Isaac Hayes is one of those cornerstones of great American music. He hasn’t gone away. He’s so well-recognized and by young people, which doesn’t mean they own a lot of old Isaac Hayes records.”

And there’s a chance other veteran Stax artists could follow Hayes back onto the Stax roster. Booker T. Jones has acknowledged discussions with Concord, and Burk says, perhaps teasingly, “a lot of those original Stax artists are still around and still have things to say.”

But however much original Stax artists may get involved in the relaunch, the core of the new Stax is likely to be just that: new.

“There are great singers who, in a modern way, fit what that Stax tradition has always meant,” Smith says. “I think it’s exemplified by Angie Stone or Lalah Hathaway. Of course, if we didn’t have Stax we’d still want to have Angie Stone on our label, making a great record. She really epitomizes what Stax is about.”

But this relaunch may be bittersweet for a lot of Memphians. After all, Stax isn’t just a name but the product of a specific time and place, a specific set of unrepeatable historical circumstances. Burk cites the way Motown has remained a viable label over the years. But even though records have continued to be released with the “Motown” imprint, that hasn’t made those records Motown. Similarly, can the new “Stax” be Stax, especially based in Beverly Hills rather than South Memphis?

“I’m not critical of that,” Deanie Parker says of the relaunch. “But I have thought about it. I take comfort in my belief that Concord is not going to put anything on that Stax label that would destroy or belittle the integrity of that brand. I am all for Stax making a quantum leap into the 21st century and providing an opportunity for today’s artists to express themselves if they have a love, understanding, and appreciation for what we did.”

“It can’t be repeated,” Burk says of the creative formula that forged Stax, “but it can be a model for an artists’ community, which is what we’d like it to be. But that’s not geographic anymore. The world has changed.”

“People buy music because its great music,” Smith says. “I think the new releases will speak for themselves. They’re certainly of great quality. Very few things stay the same or stay in one place. What Stax was at its very beginning is different from what it was in its later years. Art, the commerce of art even, evolves. Tastes change. And social and cultural influences change music. What Stax started as and what it was by 1975 were very different things, because it’s a living tradition. One wouldn’t expect anybody to make music that tried to sound like it. So, I think the question is, what did Stax stand for, and how would it have evolved going forward? I think that the kind of artists we’re signing and the respect we’re paying that label and what it stands for will be really self-evident in the records we’re putting out.”

“The kind of place that Stax Records created is not one that can be duplicated,” Parker acknowledges. “But we could emulate it, and I’d like to see that happen in Memphis.”

If you believed everything you read in Memphis last fall, you would have been under the impression that it would, indeed, be happening in Memphis, with Millington-bred pop star Justin Timberlake overseeing Concord’s Stax relaunch from here in the heart of Soulsville. But that didn’t happen and isn’t likely to.

“There are so many things that are reported, and there are so many conversations that happen that go somewhere or don’t go somewhere, and I’m not in any official capacity to be able to talk about it,” Smith says of the Timberlake rumors.

Another source close to the situation acknowledges that there were discussions between Concord and Timberlake, though the two sides never got close to an agreement about the extent of his involvement with the label. But the two sides have maintained a good relationship, and it isn’t out of the question that Timberlake could get involved in the new Stax in some capacity.

Even though the new Stax won’t be based out of Memphis, Concord executives stress that an active relationship with the city is a priority.

“We’d like to have a presence in town,” Burk says, suggesting that could come in the form of a satellite office in Memphis or the signing of contemporary Memphis artists to the new Stax, if the right situation emerged.

“We feel that we’re attached at the hip,” Smith says. “And that’s where the pleasure of working with people in Memphis, especially Deanie Parker and [original Stax] artists, is very satisfying.”

As for Parker, her hopes for the bundle of activity surround this 50th anniversary celebration are many, from financial and publicity benefits for Soulsville and its mission to tangible benefits for original Stax artists to raising the profile of Stax as a model for what’s possible in Memphis.

“Stax served its community,” Parker says. “Too much of [music today] exploits the community. This focus [on Stax] distinctly defines what music can do: economically, morally, socially, culturally. It has the capacity to do that.”

Courtesy EMI Records

Courtesy EMI Records  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum  Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum  Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum  Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Nicole C. Perugini

Nicole C. Perugini  Nicole C. Perugini

Nicole C. Perugini  Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens