Music is Memphis’ greatest export. But for the musicians, taking it on the road means long drives, long nights, and a lot of weirdness. It can be a hard life, full of ups and downs, but it sure makes for good stories. So we asked some of Memphis’ finest musicians to tell us about their Worst Gigs Ever.

Amy LaVere

I think it was the Memphis Queen. It was this new concept for a river voyage: A group of cyclists boarded for what was supposed to be a three-day cycling/boating adventure down to New Orleans. They were to port in Memphis in the early mid-morning, then they would depart the boat to go on a 40-mile bike ride. Then they would get back on the boat and have dinner, and we would be the after-dinner entertainment for their cruise.

Then they were going to stop in Tunica, where we would disembark with our gear and get ourselves back to Memphis. So the gig required us driving our van to Tunica with someone following us to bring us back to Memphis.

We get on the boat and waited around for everyone to finish a Cajun buffet dinner that had beignets and etouffee and French bread and alcohol, after they’d finished a 40-mile bike ride. They’re pretty much done. So about two-thirds of the audience goes to bed.

So right before we play, the promoter wants to introduce the band. We’re all on stage, and he gets up there in front of us and proceeds to give a speech to the audience that takes 15 minutes. It included such things as how to operate the toilets in their cabins. And we’re just standing there, wondering what the hell is going on. And then we play, and we put everyone to sleep, and it’s so sad. There were literally people with their arms folded, dozing.

When we get to Tunica to disembark, they had not reserved a docking spot for the riverboat, and the dock was full. There’s no place to dock. There’s a rocky cliff that goes up to a sidewalk/boardwalk along the Mississippi. I’m in a dress and heels, mind you. So what they did was, they basically reversed the boat, trying to stay stationary. But it was still moving down the river! It was going, like, five MPH. They lowered a plank, and I get handed down to a deck hand onto a rocky cliff that I then have to climb up barefoot with my dress up to the top. They were helping us get our gear off, but they were still moving, so by the time they got it all off, we were like a quarter mile strung out down the sidewalk.

By this point, we have a more interested audience watching us disembark than were interested at all in hearing us play. Then we had to walk our gear, piece by piece, all the way back up to the parking place at the dock. I think we made $400 on that gig, in total. Certainly the most comical and worst gig of my life.

Eric Oblivian,

True Sons of Thunder

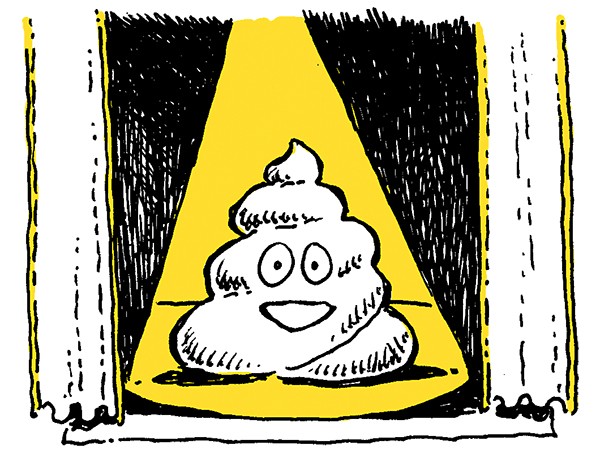

I’ve played in bands around the world. I’ve played in squats in Slovenia. I’ve played in Croatia where they had no money to give us. But the worst show I’ve ever done was right here in Memphis with True Sons of Thunder. At one point, we had a goal of playing every club in town, which included the Rally Point. We booked a show with some emo band from somewhere. We show up, and the place is dimly lit — no microphones. It was so dark, we couldn’t tell if the turd that was on stage was human or canine. The show went on, and we did the show without vocals. We just sang into the air. We did our set, got out of there, and to my knowledge, the turd was still there while the other band played.

Alicja Trout, Rich Crook, and

John Garland, the Lost Sounds/Sweet Knives

AT: There was one that was just an epic night of bad things happening. The Vibrators wanted to get on our show in Detroit at the Old Miami club. We were playing with the Piranhas and Guilty Pleasures. The Vibrators were playing down the street, and they had this promoter named Lacy, and he says, “We’re playing down the street, and there’s nobody at our show. Can we come down and play with you guys?” And we said, “No, we’ve already got three bands . . .”

RC: We eventually said yes, but we weren’t going to share any money. And the Vibrators were HORRIBLE that night.

AT: I had this Peavy amp that had a phaser built in. I asked the guy if he wanted me to show him how to use the amp, because he was borrowing my stuff, rudely enough.

RC: … and he was like, “I think I’ve played enough amps!”

AT: So the phaser was turned all the way up, because we had ended the set with this big noise thing. And he played the whole show going “wheew … wheew . . . wheew…” He never figured it out. Then, one of the funniest things Jay [Reatard] ever said in his life…

RC: Dude said a lot of funny things.

AT: He said the dude from the Vibrators looked like Jimmy Page’s nutsack. He was balding and like had really wiry, black hair.

RC: Phil Spector-ish.

AT: It ended with this giant bar fight. The promoter walks in with a giant block of concrete. The cops come, and I kept saying, “Yeah, the puff-mullet. You know those guys with the puff mullets?” And everyone was like, what is she talking about?

RC: Turned out the guy had a goiter on his neck with hair growing out of it.

AT: I thought it was a mullet.

RC: I was outside the whole time. I walked in, it was like a saloon piano was playing. John got slid across the bar.

JG: I saw Alicja get punched, so I went in.

AT: Oh yeah. I got punched right in the face. The bartender came up to me, and this dude’s fist was coming right at me. He grabbed me. ‘You gotta get out of here! You’re gonna get killed!” He was carrying me out, and I was like, “Where the hell am I going?” Jay comes out of the bathroom. He’s been doing coke with this guy from the other band. They looked around and realized, “Gahh! We’re enemies!” They started going at it.

Chris Davis, Papa Top’s West Coast Turnaround

This would have been sometime in the late 1990s. We had just played a gig at Kudzu’s, and we had a little liquor in us. The only piece of parental advice (guitarist) John Stiver’s father ever gave him was, “Stay away from Harpo’s Lounge. You’ll get killed.” So we decided we would see if they would let us play for beer. This is a self-inflicted gig. It was our own fault.

Let me first say that Harpo’s has reopened, and it’s nice. They’ve gentrified it. Back then, they self-described it as the most redneck place on Earth. It was infamous for finding dead hookers out behind it.

The minute we walked in, we could see that there were more people than teeth here. It was all rebel flags and unfinished plywood. There was a lot of drug dealing, a lot of meth. So there were a lot of working ladies. They made it clear we were different and unwelcome.

I had on a sequined, knock-off Nudie suit jacket. There was a guy following me around saying, “I’m gonna go home with that jacket!” There was a working girl who looked like Grandma from the Addams Family. She was saying I looked like Elvis, and she was going home with me.

John Whittemore was playing pedal steel, and he had a woman who was reaching around him with one hand on the hand he was picking with, and the other hand he’s barring with. Grandma would walk around behind me, and when I would be singing, and my hands occupied with the guitar, she would reach up between my legs and start squeezing my business. It got a lot easier to hit those high notes.

Was this a bad gig? I guess it depends on how you define gig. We just sort of showed up. They didn’t want us. But by the time it was over, there were people calling out requests. We did our usual set, and played Elvis’ “Little Sister.” That was when the guy who was going to knock me in the head and steal my jacket decided we were okay. He wasn’t going to knock me in the head, but he was still probably going to take my jacket.

Marcella Simien,

Marcella and Her Lovers

We were playing this outdoor festival, and I was handed a note in the middle of a song asking me to announce that a 6-year-old boy was missing and had been for over an hour. They made it sound like this kid just took off — a little renegade. I smiled to myself at first, thinking “Okay, the kid is probably off doing things 6-year-olds do.” Then it started to sink in.

I’ve gotten notes on stage with song requests, marriage proposals, birthday requests. But a missing persons report? This was a first, real “Stop the presses!” kind of stuff. So I made the announcement, and the stage manager motioned for us to continue, to keep playing. So we did. But the whole time there was this feeling, this undertone of … missing kid … impossible to ignore. I mean, how can you not be concerned?

Several songs later the kid still hadn’t shown up, and no one was any the wiser as to where he might have been. Someone from the sheriff’s department got onstage and made another announcement as the band and I helplessly looked at each other, eyes all big. This person makes the announcement sounding like the conductor of a train and then hands the mic back to me. Somehow we finished the set, packed up, and headed out. But not before leaving behind a suitcase full of our merchandise. Thankfully we got word on the drive home that the child had been found. He pedaled his Big Wheel back on up to the house like nothing had happened.

Steve Selvidge

Big Ass Truck was playing at a fraternity down in Oxford. They paid well. That show would finance a whole tour. And people usually had a good time. It was in our contract that you were hiring us to be us. We weren’t going to play Dave Matthews or Phish. We’re playing outside at this crawfish boil. It’s an all-day thing. People were getting drunk. Some kid thought it would be funny while we’re playing to flip the breakers. So we’re playing, and the power cuts. That happened all the time — it’s no big deal — you just have to sit there and wait for it to come back on. So we start playing again, and the kid flips the breakers again. Power goes off. It keeps happening!

Finally, the sound guy figures what’s going on. “There’s a kid flipping the breaker. We dealt with it.” But it messed up the P.A. The monitors went out, and we couldn’t play. With a DJ, we needed the monitors, because we’re playing to him.

People didn’t understand why we wouldn’t play, and they were getting restless. This entitled little fuck frat kid hops up on stage, grabs the mic, and says “Big Ass Truck sucks!” I was livid. I got up and I was just like, “Get the fuck off my stage you little shit.” Then the monitors come back on, and I’m like, “Hey, sorry about that! Let me tell you what was going on. We’re here to play and have fun. It’s gonna be a good time. But that little fuck who was flipping the breaker on and off, your mother [string of shocking expletives deleted].” Should have taken the high road. But I didn’t. Then we just light into the set. We were furious. It was fun. Next thing you know, there’s a bunch of people who want to kick my ass. I’m looking at guys in the crowd mouthing, “I’m going to kill you!”

Joseph Higgins, Chinese Connection Dub Embassy

The worst gig was one of the first gigs we played out of town. It was just a trip to Nashville. Everything was going great, then 30 minutes out of Nashville, our front tire pops off and drags the car a quarter mile down the expressway.

So we get the tow truck to come and get us, and then we find out we have to go to the nearest place to get it fixed before we can do anything. So our bass player, Omar, and Paul, our guitarist at the time, and my brother David head to the Walmart to change the tire out. This is in the middle of summer, and it’s got to be 105 degrees. Two of us are in the tow truck, and the other three are in the car.

We finally get to Walmart after driving around everywhere looking for it. We’re desperate to get to Nashville to play the gig. This was on a Saturday, and all of the places to get a tire fixed are closed. Then we find out we need over $800 worth of work on the car before we can do anything. We had to call some friends and family to see if we can find anyone to take us to the gig. The guitarist called his family to come and get us. He was so angry at the whole thing, he just wanted to go home. We were like, “No man, we should at least go to Nashville, play the gig, and make some money to pay for the car!” But he was all flustered. “We can’t do this. Let’s just go.”

After we come back to Memphis, we find out later that night that the venue we were playing — it was called Nash Bash — had over a thousand people at the show. We did know it at the time, but we were one of the headliners. We find out there was a big crowd waiting to see us, because there was no reggae on the bill. Then we find out the promoter for the show lives in Franklin. He could have picked us up and taken us to the show and brought us back. It literally could have all been fixed if we had had the promoter’s number on hand. Since then we have a backup plan for everything.

Jonathan Kiersky, Club Owner

Without naming names, this was the worst: It was a Brooklyn four-piece — three synthesizers and a drummer. They had a bunch of press and a strong booking agent, so I booked them. Not sure how they had so much professional support, except it was the heyday of the indie pop scene in Brooklyn. One of them may have been a model.

Early on, we realized this show would be a mess, since it was their first tour, and set up and soundcheck were a disaster. Show starts, and the vibe on stage is complete fear. Finally during the third song, the lead singer/synth player just yells “Stop, stop, stop!” and starts weeping on stage. We hoped she would pull it together and the show would go on but that was not the case. They just walked off stage, packed their shit up, and left. My jaw had never been closer to the floor.

Chris Milam

Friday night in Gloucester, Massachusetts. The bar was packed, the crowd homogenous: male, bearded, titanically drunk. Picture the cast of Perfect Storm meets the cast of Jersey Shore. And I was scheduled to play for two hours, solo acoustic.

Somehow, they liked me — too much. A mosh pit formed — onstage. One guy insisted on “freestyling to his lady.” Another swiped at my guitar mid-song, “helping” me play. The night got later, the crowd drunker, would-be fights started popping up around me. It was a farce; a mostly-improvised, slightly-violent farce.

When I finished, I hustled my gear out to my car. I came back to find a waitress literally stiff-arming a man away from my night’s pay. Come to think of it: I made it out in one piece, my guitar made it out in one piece, and I got paid in full. I’ve had worse gigs.

Brennan Villines

I was playing with my trio years ago at my uncle’s house for a pool party in Arlington, which is as amazing as it sounds. My music doesn’t necessarily lend itself to a backyard full of Gen X white people who have musical tastes spanning from George Strait to Kenny Chesney. We were asked — yelled at — to play a certain song, the name of which I cannot recall at the moment. I remember being disgusted at the request coming from the drunkest person at the party.

I said I didn’t know the song and continued with my set. He called me a queer and threw a wet towel at my face from about 25 feet away. The towel smacked me surprisingly hard … in mid song. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t impressed with his throwing ability, given the distance factored with his blood alcohol content. But, this was definitely a low point in my career. Just as I was feeling defeated, my uncle pushed him in the pool, and we all had a good laugh.

Andria Lisle, Music Journalist

The worst gig I ever attended was one I knew would be awful going in. I expected, and got, the worst on November 16, 1991, when I walked through the doors of Antenna to see G.G. Allin and the Murder Junkies.

It was the pre-internet age, so what I knew of G.G. Allin was gleaned from the pages of MAXIMUM ROCKNROLL and via first-hand stories from friends who had caught Allin on the road in other cities. Self-billed as “the last true rock and roller,” Allin would take Ex-Lax before his gig, then defecate on stage. When the Memphis stop on his fall 1991 tour was announced, I should’ve wondered “Who on Earth would want to attend something like this?” Instead, I thought, “Who would want to miss it?”

I paid my $5 and cautiously took a post in the back of the room, close enough to the door that I could escape if necessary. I can’t remember who opened or what songs were on the Murder Junkies’ setlist. Allin wore a black hoodie, his pale ass gleaming under the lights. He paced the stage, drinking beers and throwing the bottles into the audience. He had the frightening intensity of Charles Manson — I recall being too afraid to meet his gaze. At some point, the microphone he ranted into went up his ass. Later, Allin leapt off the stage and began antagonizing the audience at close range. Most of us ran out of the door of the club.

He’d chase us outside, then stop at the corner of Madison and Avalon while we raced to the relative safety of the Piggly Wiggly parking lot. For some reason, that happened more than once. I have no idea why I didn’t just leave at that point, but I kept going back in for more. Finally, Allin chased us out again, and one audience member ran to Murphy’s and came back with a knife. She began chasing G.G., and that was too much for me. I went home, took a long shower, and questioned every decision I’d made in life.

Chris Shaw, Ex-Cult, Goggs

Every time a band goes on tour there are shows that inevitably get highlighted for various reasons — you’re playing with friends, you like the venue, the gig pays well, or there’s promise that someone who “needs to see your band” will be there. Ex-Cult had just released a new record, and so we were working with a new publicist who had promised to gather all her industry friends for a show at Mercury Lounge, the Manhattan venue that is known for being a “music industry hotspot,” whatever that means.

This show was on my radar from the beginning of the tour. We performed in Baltimore the night before, but because of a sound ordinance, we had to soundcheck at some ridiculous time, like 2 p.m. the day of the Mercury Lounge show.

We left Baltimore on time, but to make sure all goes according to plan, I decided to drive into Manhattan. I was driving like a bat out of hell, impressed with my band mates that we are all up and moving, hangover-free and ready to hit New York City. Then my phone starts going off. Repeatedly. I’m driving so I can’t look at my texts. Then our booking agent called, annoyed I haven’t been answering the phone.

What comes next is something I’ve never heard happen to any other band: A pipe burst in front of the venue, and a rather large sinkhole formed outside of Katz Deli, literally next door to the Mercury Lounge. The show was cancelled. Best of all, the publicist with all her industry contacts has gone AWOL. I don’t hear from her again for the duration of our time in New York City. Maybe she fell in the sinkhole?

Do you remember the scene in Ferris Buellers Day Off when Bueller’s buddy Cameron screams as the camera pulls out to show all of Chicago? That’s how I felt. The show eventually got removed to a lovely little club called Fontanas, but as you have probably guessed, no one came. What doesn’t break you makes you stronger, so when this exact same scenario happened to us a year later in San Diego, all we could do was laugh.

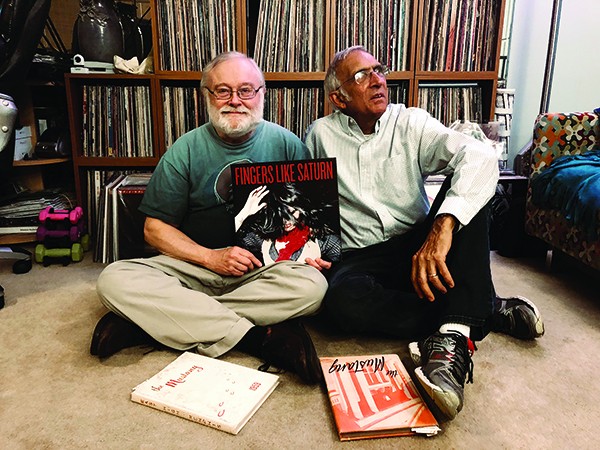

Dan Ball

Dan Ball

Rich Tarbell.

Rich Tarbell.