Memphis: Sweet, Spicy & a Little Greasy

By Susan Schadt and Annie Bares; photography by Lisa Buser

Wild Abundance Publishing; 253 pp.; $45

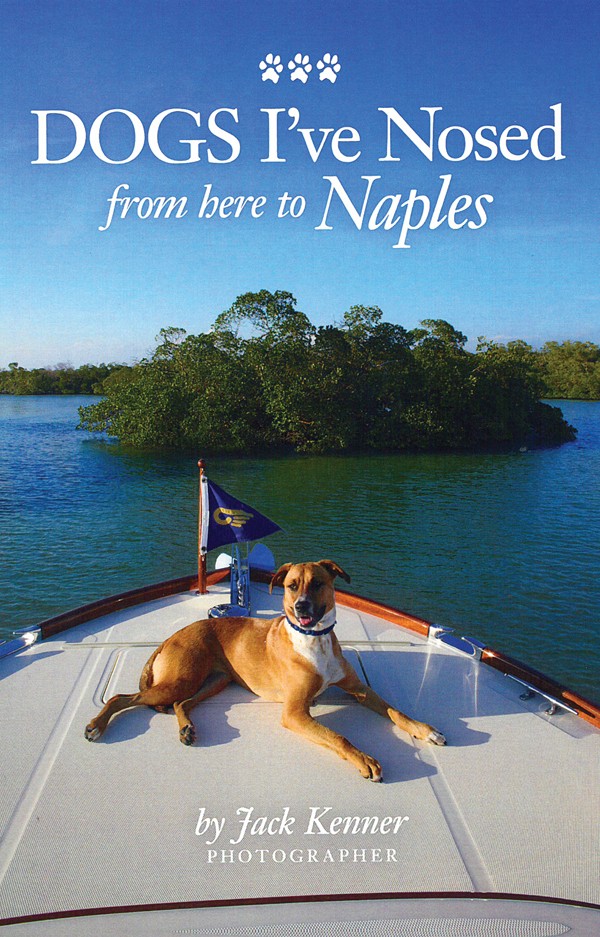

Dogs I’ve Nosed from Here to Naples

By Jack Kenner

Self-published; 166 pp.; $39.95

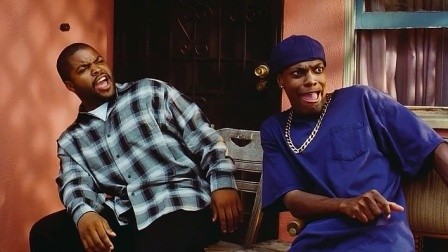

Memphis: Sweet, Spicy & A Little Greasy, the new title from ArtsMemphis-spawned Wild Abundance Publishing, is a whole lot of fun. It’s a hybrid of sorts — part coffee-table book, part cookbook, and part yearbook, detailing ArtsMemphis’ 2013 culinary arts series. These 12 parties mixed the best of Memphis’ art scene. Held at the homes of the city’s most influential art patrons and other venues, the parties featured dancers, actors, visual artists, and musicians performing while guests noshed on meals created by the area’s most notable chefs.

The book’s vibrant pictures, taken by Lisa Buser, show these events in full swing. In one striking image, Valerie June is seen mid-strum and mid-wail during the elaborate three-day Foxfield event held at Michelle and Bill Dunavant’s farm. In another, taken at the Homegrown Treasures party at the Hyde Foundation, chef Andrew Adams beams over a vehicle’s backseat absolutely crammed with pots and pans. Throughout are pictures of guests dancing and eating and celebrating. Chefs — Kelly English, Karen Carrier, Mac Edwards, Erling Jensen, Patrick Reilly, Jason Severs, Jackson Kramer, among them — are shown cooking and mingling and toasting a meal well done.

The recipes in the book can be used for your own fabulous parties — from Mac Edwards’ Gibson’s Donuts Bread Pudding and Burch Brown’s Stax Funky Frog Leg Ragout to the Veggie Chorizo Tortellini by Justin Fox Burks, Amy Lawrence, and Andrew Adams and the Quail Stuffed with Bison and Truffles by Erling Jensen.

Memphis photographer Jack Kenner’s Dogs I’ve Nosed from Here to Naples is his third book of animal portraits, but this book comes with something a little extra: recipes for pets. Many of the recipes look fine enough for your own dinner.

Like Memphis: Sweet, Spicy & A Little Greasy, you’ll recognize some names here. There’s Kelly English, his belly covered by his three adorable little dogs: Pappy, Shelby, and Benton. His recipe is Chicken Fried Rice. Karen Carrier — “lapped up” by her two big hounds, Otis and Sadie — suggests sharing a bowl of her Chicken and Rice Casserole. Ben Smith offers With Fish, a raw fish dish with kale, rice, and egg, which he feeds to his dogs Juno and Hobbes.

The “Naples” in the title refers to Naples, Florida, where Kenner had an exhibit of dog portraits, which are included here. In his introduction, he mentions how he prefers to shoot his subjects in their own environments. From the weest canaries to the greatest Great Dane, Kenner’s images present these animals at their finest — loved and loving. — Susan Ellis

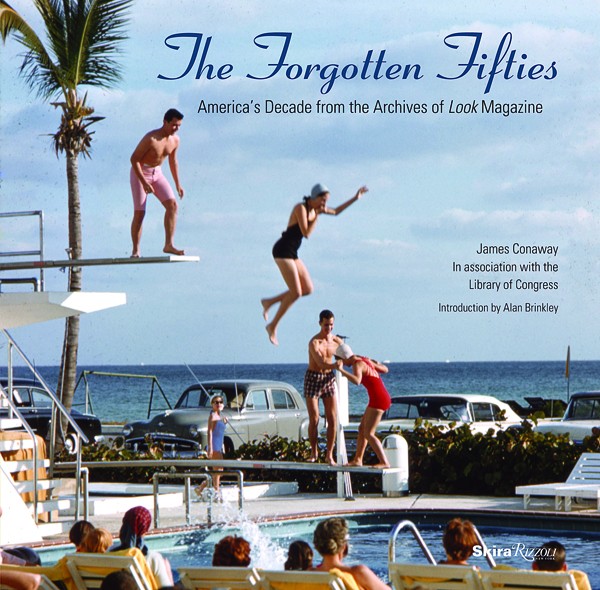

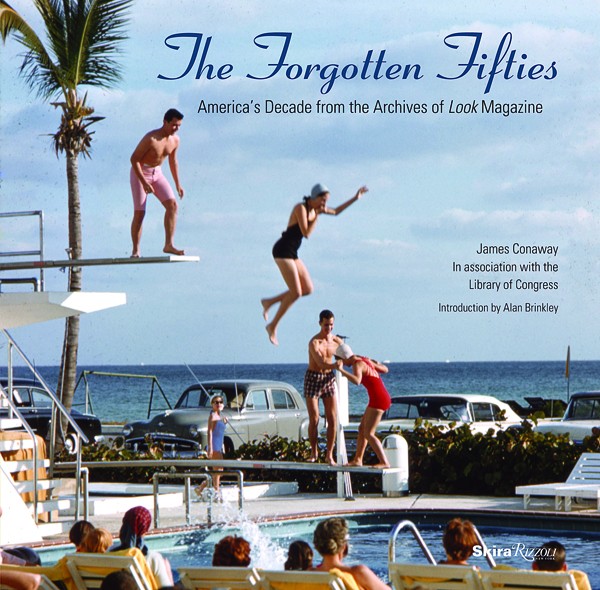

The Forgotten Fifties

By James Conaway

Skira Rizzoli; 237 pp.; $45

“What Were We Thinking?” “Be Afraid.” “Are You Now or Have You Ever Been.” “Light, Cheap, Everlasting.” “And Then It Was Over.”

Those are some of the chapter titles used to describe 1950s America, and the book is The Forgotten Fifties by James Conaway.

Conaway — a novelist, journalist, and travel writer who grew up in Memphis and now lives in Washington, D.C. — knows this decade, as anyone who’s read his memoir, Memphis Afternoons, also knows. In The Forgotten Fifties, he takes a national look at those years, but this is no dry rehashing of the decade that brought us the Korean War, UFO sightings, Joseph McCarthy hearings, “I Like Ike” banners, frozen foods, the polio vaccine, black-and-white TV families, and whites-only dry cleaners.

To write this handsomely designed, coffee-table-size book, Conaway had access to the photo archives, housed in the Library of Congress, of Look, a magazine that at the height of its popularity had a peak circulation of 7.75 million. What does that number tell you about the influence Look had on the way Americans viewed themselves? That’s a question Conaway repeatedly asks. And what was Look‘s mission? To combine reporting with top-notch photography, and that’s what Conaway has done here: He’s written a series of essays — one essay per year of the decade — in the collective voice of the first-person plural to comment on the images he culled from the archives. Some of those images you might remember. Many of them you could not have remembered, because Look never published them. And it’s precisely what wasn’t published back then that may say more to us right now.

If you lived through the Fifties, it’s still a good question: What were we thinking? After looking at The Forgotten Fifties, later generations will want to rephrase that, with added emphasis: What were they thinking? — Leonard Gill

Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief

By James M. McPherson

Penguin Press; 300 pp.; $32.95

To say the least, the historical reputation of Jefferson Davis has suffered from what, today, we would call bad press. The leader of a failed rebellion against the United States, a defender of the institution of slavery, a military strategist whose decisions have evoked near universal scorn, a personality considered flinty and secretive — all this does not inure to the admiration of posterity.

Even among the partisans and commemorators of the Confederacy, Davis exerts an uncertain hold, as witnessed in the relative indifference — locally, anyhow — to the recent change of name for Jefferson Davis Park in downtown Memphis compared to the anguish and protest that met the renaming of Nathan Bedford Forrest Park nearby. Both retired to Memphis after the war. Perhaps the difference is that Forrest’s remains are still here, interred in the formerly eponymous grounds, while Davis, an erstwhile Mississippian who operated an insurance company in Memphis for a while and lived in The Peabody, would move on to a series of residences elsewhere in his former Confederate domain.

In any case, as James M. McPherson’s Embattled Rebel makes clear, Jefferson Davis was always a remote figure, even in his own sphere in his own time. One of the accusations against him is that he was overly partial to a few intimates — Braxton Bragg as commander of the South’s ill-fated military operations in the western theater, say, as well as a series of ill-equipped “political generals” elsewhere.

While acknowledging that charge and numerous others, McPherson — a Pulitzer Prize winner for his Battle Cry of Freedom and no sympathizer for the Confederate cause — is at pains to balance the historical record in Davis’ favor. Bragg, for example, he sees as unfairly maligned, a competent general overall, especially as compared to such darlings of the historians as the ever-hesitant General Joseph E. Johnston, a bête noire to Davis throughout the war.

In the same way that Abraham Lincoln was able to discern the virtues of Ulysses Grant and elevate him to a de facto personal partnership, so was Davis able to do so with Robert E. Lee, whose advice he took in most matters, especially in the policy of taking the war to the North, as at Antietam and Gettysburg. In order to maintain a flow of troops, as well as fiscal and political support from the states of the far-flung Confederacy, Davis was obliged to spread his resources thin, however, and that would ultimately prove an untenable strategy.

McPherson notes that Davis, a hero of the Mexican War, was chosen by the organizers of the Confederacy to be president of a fledgling breakaway nation certain to face a challenge to its existence because of his presumed military prowess. As a plantation owner and slaveholder, he was (and would remain) a firm believer in white supremacy and the South’s “peculiar institution.”

What is unfamiliar to most people is that, in the desperate last days of the Confederacy, as McPherson documents, President Davis had sent Secretary of State Judah Benjamin abroad to solicit British and French support in return for a promise of eventual abolition of slavery. And Davis was attempting to fast-track his own version of an Emancipation Proclamation — a massive granting of freedman status to whichever slaves would agree to provide last-ditch military service in defense of his shrinking realm. Companies of black soldiers were being organized even as Richmond finally fell in April 1865.

The ironies of all that are obvious — underscoring the several coincidences that relate Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln, both Kentucky-born and both veterans of Congress, each of these gaunt eminences a legitimate spokesperson for an opposite side of the great racial issue that divided, and in some ways continues to divide, the unity of the North American continent. — Jackson Baker

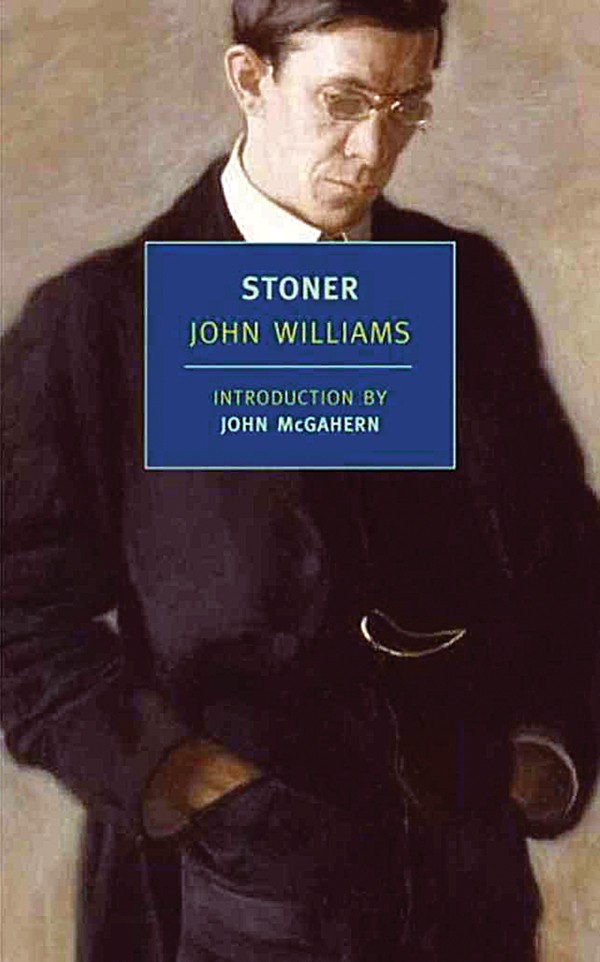

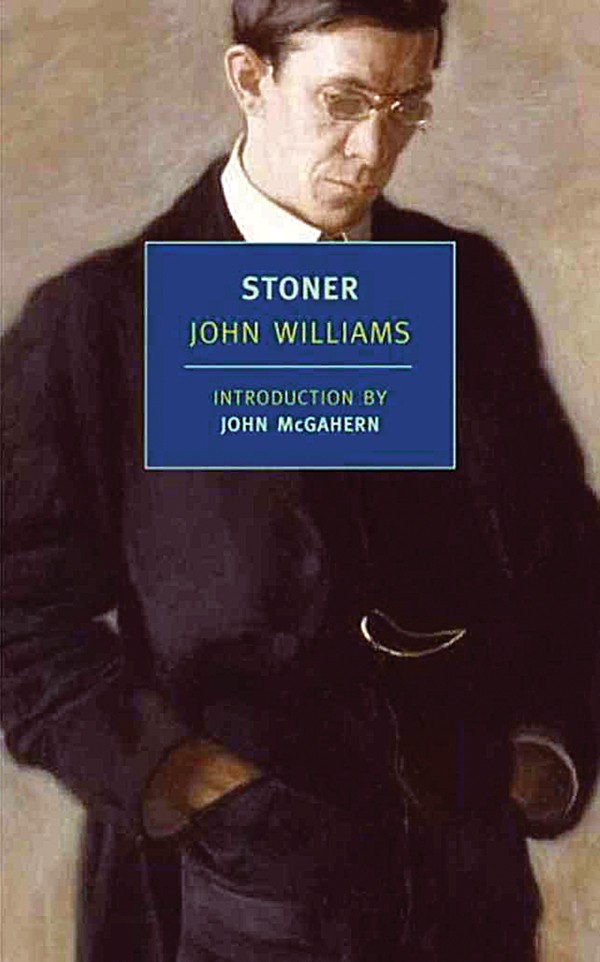

Stoner

By John Williams

New York Review Books Classics;

288 pp.; $16.95 (paper)

Dude! How have I never heard of this book? Well, it turns out John Williams’ Stoner (first published in 1965) isn’t about my college years at the University of Missouri, but oddly enough it is a novel set at the University of Missouri. It’s the life story of a fictional professor — one William Stoner, born at the end of the 19th century on a hardscrabble piece of land near Booneville, the only son of a dirt-poor farmer and his wife. In the summer of William’s 18th year, his father surprises him by suggesting that William should consider going off to the university in Columbia, some 15 miles away, to study agronomy. In four years, his father says, William could come back to the family farm with new ideas, maybe some ways to make their lives easier.

And so Stoner begins, a deceptively simple story of a farm boy going off to college. William doesn’t really fit into academia at first. His clothes, his appearance, his ignorance of collegiate life trouble him: “He became conscious of himself in a way he had not done before. Sometimes he looked at himself in a mirror, at the long face with its thatch of dry brown hair, and touched his sharp cheekbones; he saw the thin wrists that protruded inches out of his coat sleeves; and he wondered if he appeared as ludicrous to others as he did to himself.”

But an odd thing happens: Stoner takes a required English class and becomes enthralled with a Shakespeare sonnet and with the music and complexities of language. His English professor takes a liking to him, and William’s interest in agriculture slips away. After four years at school, he is offered a small stipend to teach English and accepts, setting the course of his life away from farming forever.

It’s a small life. William naively marries an unhappy, spoiled woman who makes his days miserable. He gets caught up in the petty machinery of faculty politics; he angers the wrong colleague, who rises to power and makes Stoner’s tenure a career-long struggle. He falls in love with a beautiful young grad student and has a magical but ultimately ill-fated affair. His life opens up briefly and closes again. He settles back into his marriage. He grows old. He dies in his own bed.

Stoner seems on the surface a simple, tragic tale of a life lived in quiet desperation. And it is. But its simplicity and its clear, declarative prose generate a slow irresistible power. You can’t put it down. Williams has written one of the great, unheralded works of 20th-century fiction. — Bruce VanWyngarden

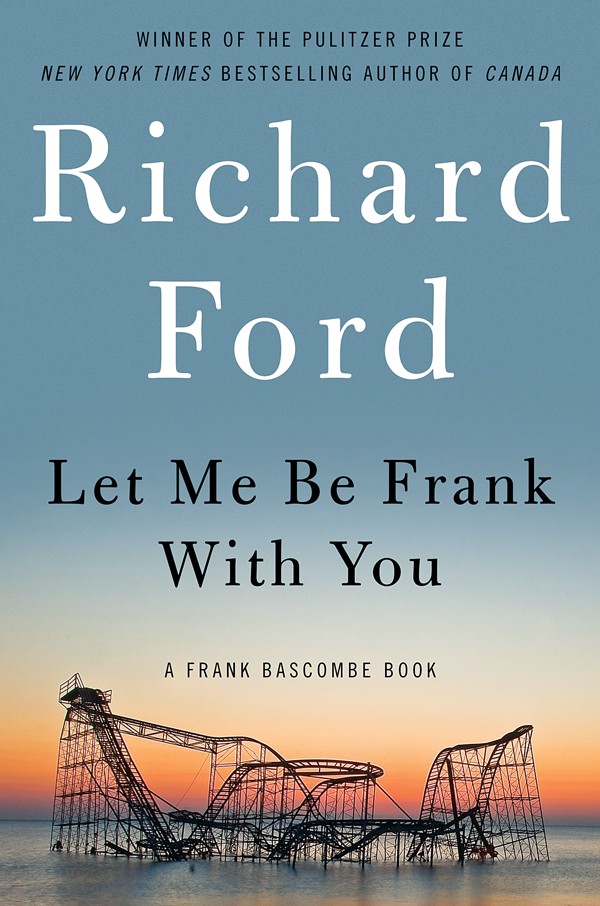

Let Me Be Frank With You

By Richard Ford

HarperCollins; 240 pp.; $27.99

Frank Bascombe is back. The recurrent protagonist of author Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter, Independence Day, and The Lay of the Land is now 68 years old, retired from real estate, and volunteering on behalf of the blind and of soldiers returning to the States from Afghanistan. Living downsized with his wife Sally in Haddam, New Jersey, where we first encountered him in the 1980s, now Frank experiences a body’s response to passing time as he ruminates on the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy and other of life’s vagaries.

In this collection of four short stories, Frank regards the altered Jersey shoreline with somewhat the same detachment that he scrutinizes the cosmetically altered features of a former client’s face. Within his own home, he discovers a past that shattered other lives but barely scratches the surface of his own. Awareness of two old deceptions affects him in surprising proportions.

The conclusion of each story leads to the beginning of another. Ironically, in Frank’s willfully decluttered language, there is a touch of the sparse-at-all-costs feng shui decorating style that this proud misfit finds so discomfiting in the stylish, almost clinically decorated apartment inhabited by his ex-wife, a victim of Parkinson’s.

But his, in its own way, is a cluttered life. Frank begins the pre-Christmas season by feeling not guilty but “implicated by everything’s dilapidation.” He yields to an unwanted embrace by observing, “Our sympathies are most required when they seem less due.”

Unless severe weather keeps him grounded, Frank can anticipate with some pleasure a trip to Kansas City, where his son’s business ventures teeter between solvency and devastation. A day can be saved, Frank still believes, by “a few good words” — presumably a credo shared by author Richard Ford. — Linda Baker

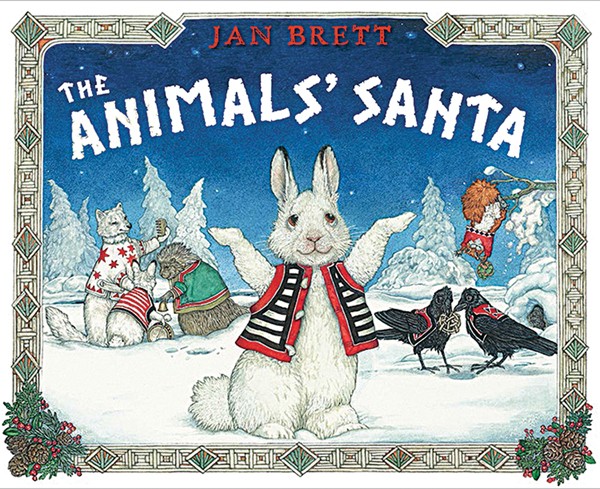

The Animals’ Santa

By Jan Brett

Putnam; 32 pp.; $17.99

Bestselling author and illustrator Jan Brett has released another beautifully crafted children’s book just in time for Christmas. In The Animals’ Santa, a rabbit named Big Snowshoe tells his younger brother, Little Snow, about the mysterious animals’ Santa, who stealthily delivers presents to all of the forest animals each Christmas. Big Snowshoe and his animal friends all have guesses as to who they think the animals’ Santa might be (is he a thick-coated badger? a blizzard-resistant polar bear? a sure-footed moose?), but Little Snow, who is celebrating his first Christmas, thinks the idea is silly. That is, until he comes face to face with the animals’ Santa himself.

The Animals’ Santa is an adorable tale for the holiday season. The story and detailed illustrations by Brett will transport children into a magical world of friendly, talking animals and introduce readers to some of the creatures that inhabit the snowy forests of northern Canada. — Hannah Anderson

On Thursday, December 4th, Memphians can introduce themselves to Jan Brett. The Booksellers at Laurelwood is hosting a book signing with Brett and her hat-wearing hedgehog, Hedgie, at the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library from 5 to 7 p.m. The event is free, but line tickets are required and are included with the purchase of The Animals’ Santa from the Booksellers.

Leo’s Other Christmas

Written and illustrated by Graham Sale

Little Black Book Press; 29 pp.; $9.95 (paper)

Graham Sale may have once been an editorial cartoonist for The Commercial Appeal, but he sure has a way with words in his holiday children’s book, Leo’s Other Christmas. The story, based on a true story from Sale’s own past, centers around a boy who certainly loves toys — he loves dreaming about them, making lists of them, and receiving them at Christmastime. Leo is a well-behaved child — maybe a little spoiled — who just doesn’t know any better, but once he opens his eyes to the troubles of others, he realizes that Christmas is even more special once we open our hearts to those less fortunate. When it comes time to help a family in need, we see Leo’s journey, which starts out begrudgingly, lead to compassion.

Leo’s Other Christmas is an adorable spin on an old lesson — Sale’s illustrations are half the fun — but it’s a lesson worth retelling. And it might just inspire adults to ask themselves too, “What else can I do?” — Alexandra Pusateri

Leo’s Other Christmas is available at the Booksellers at Laurelwood and Burke’s Book Store. To order, go to the author/illustrator’s website, grahamsale.com.

Memphis Type History:

Signs and Stories From Just Around the Corner

By Caitlin L. Horton;

illustrated by Rebecca Phillips

Saturday Morning Press;

149 pp.; $39.95

You see the signs everywhere — the rusty, well-worn, retro relics of a bygone era. Those fading, hand-painted murals and vintage neons give a glimpse into Memphis’ past, days when movies cost a quarter and a young Elvis Presley could be spotted around town.

There are a wealth of stories behind those signs and the places they represent — some long boarded-up, others still very much in business. And that’s the premise of Memphis Type History: Signs and Stories From Just Around the Corner.

Each chapter features a painting of an iconic sign by Rebecca Phillips, as well as historical images and additional current-day photographs by Jeremy Greene. The history of the signs and the places they represent are told through personal stories, collected by author Caitlin Horton.

Featured are the Universal Life Insurance Company sign on Dr. M.L. King Jr. Avenue, the old Chicago Pizza Factory sign that was replaced with Chiwawa’s “Midtown Is Memphis” sign, the Sputnik sign at Joe’s Wines & Liquor, the dancing-lady sign at Drink-n-Drag (formerly Club Spectrum), and the Skateland roller-rink sign, among others.

The book is filled with personal accounts of mid-century Memphis life. In the chapter on the Lamar Theater, a woman remembers the old serials and Westerns featuring Hopalong Cassidy that screened on Saturdays. The pages dedicated to Leahy’s Trailer Park on Summer contain a childhood love story and snippets of the truth — James Jones put his finishing touches on From Here to Eternity there — and of legend — Machine Gun Kelly supposedly frequented a bordello in the front of the park.

The “Memphis Type” project began in 2009 when photographer Greene began documenting old and overlooked Memphis signs just for fun. He sought out signs with compelling type as well as interesting graffiti. Phillips was inspired to base paintings on the signs, and Horton helped her sell some of them on her website, FrontPorchArt.com. It wasn’t long before a book deal was born, and Horton began collecting stories from Memphians.

If you’ve ever marveled at the “dripping” neon radiator sign on Walker Radiator Works and wondered who maintains that vintage treasure, or if you’ve spied that rusty Normal Beauty Shop sign on Highland and thought, What’s so normal about that place, anyway?, you’ll find those answers (and so much more) in Memphis Type History. — Bianca Phillips

Caitlin Horton and Rebecca Phillips will be signing Memphis Type History at Burke’s Book Store on Thursday, December 11th, from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m.

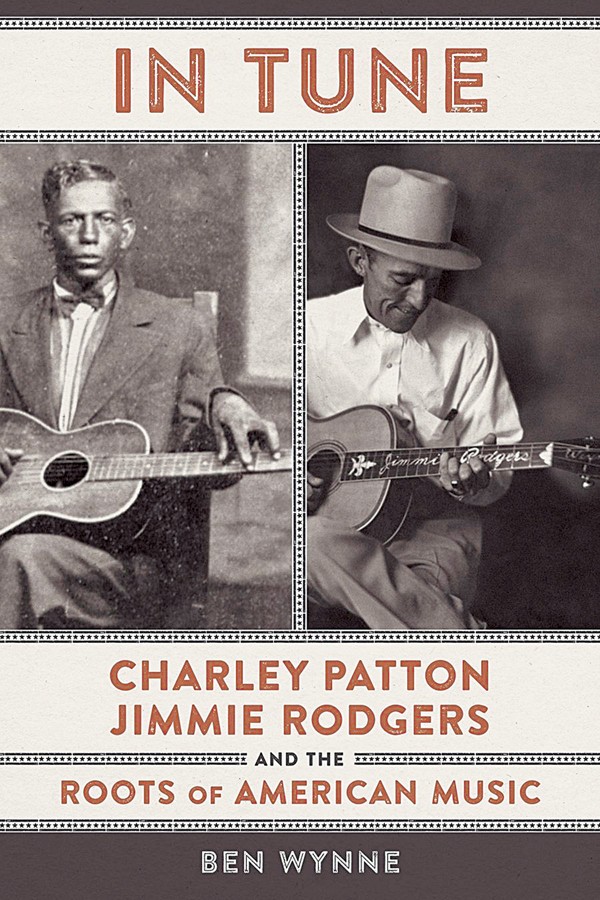

In Tune: Charley Patton, Jimmie Rodgers and the Roots of American Music

By Ben Wynne

Louisiana State University Press; 270 pp.; $38

Jimmie Rodgers and Charley Patton represent a fork in American popular music traditions. But the two men were clearly drawing inspiration from the same deep wells, and the far-reaching influence of songs like Rodgers’ “Blue Yodel #1” and Patton’s “Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues” is unmistakable in the work of pioneering artists like Bill Monroe and Elvis Presley.

Ben Wynne’s new book In Tune: Charley Patton, Jimmie Rodgers and the Roots of American Music, functions as backstory for the Elvis myth, as it describes the life and hard times of two poor-born men from Mississippi who came of age in the post-Civil War South and who went on to become American music royalty. In Tune tells the parallel but markedly dissimilar tales of Rodgers, the King of Country Music, and Patton, the hard-living Delta Blues King. The real narrative, however, is how both men used music as a means of transcending the boundaries of race and class.

Wynne, associate professor of history at the University of North Georgia, has written extensively about Mississippi and the Civil War. Although the author has a strong sense of the two artists’ musical kinship and their impact on popular culture, he’s at his best contrasting the social and economic conditions impacting the lives of Rodgers’ peripatetic family as it pushed westward in search of opportunity and Patton’s attempted escape from plantation culture.

Wynne’s research suggests that Patton the man may have been the equal to Patton the myth. He was small of stature, with a big, penetrating voice and an equally large appetite for whiskey, women, and trouble. At a time when mobility was a measure of success, Patton seems to have regarded music as a way to escape a conventional life on the farm.

Rodgers was called “The Singing Brakeman,” but he never much cared for the image. He was still a kid with stars in his eyes when he ran off to sing and play guitar with a medicine show. When his first attempt at a career in show business didn’t work out as planned, Rodgers went to work on the trains.

Steeped in a puritanical ethos where playing music and work were two entirely different things, In Tune shows that, in spite of segregation, Patton and Rodgers both “drew on the human condition for their subject matter,” Wynne writes. “Both men recorded songs with a wide range of themes from religion and death to hell-raising and sex. Both men played with other musicians on occasion but were, in essence, solo performers, more comfortable with a guitar than any kind of manual labor.” If not for their gifts, the author concludes, Patton would have been just another sharecropper, while Rodgers might have spent his adult life “grinding out” a meager living. “Because they could play music, other people noticed them,” Wynne writes. But as conclusions go, that’s something of a letdown. — Chris Davis

Jerry Lee Lewis: His Own Story

By Rick Bragg

Harper; 481 pp.; $27.99

Jerry Lee Lewis deserves a biographer on the order of William Manchester, Carl Van Doren, or Walter Isaacson. Rick Bragg’s biggest problem in biographying the Killer is Nick Tosches’ Hellfire, a comparatively rhapsodic and better-written account of Lewis’ life. But Tosches, like his subject, has his demons: He’s writing about the myth of the Killer, not the man. This hindered his insight into and access to the most important and talented white personality from the rock-and-roll era. Tosches gets carried away like a screaming fan boy and fails to contextualize a man whose actions bear further scrutiny. But his is a cool book.

Any old man can tell you cool ain’t everything, though. Bragg gets the larger, more difficult job done. For all of his tube-biscuit eloquence, Bragg knows the Deep South. Even if his subject is living in the dark as his own ghost, Bragg makes the most of his time with Lewis, coaxing details out of the old stone. One would imagine that a properly snobbish intellectual wouldn’t get too far. So it’s a compromise — sort of like the Killer’s career after his fall from grace. Bragg, our man in Nesbit, is not the ideal candidate, but at least we get a fuller picture of a superhuman piano man haunted by the thrill of lust and the terror of fate. — Joe Boone

Rick Bragg will be discussing and signing Jerry Lee Lewis: His Own Story at the Booksellers at Laurelwood on Saturday, December 6th, at 6:30 p.m.

I Never Met a Story I Didn’t Like: Mostly True Tall Tales

By Todd Snider

Da Capo Press; 295 pp.;

$16.99 (paper)

Stories have been a hallmark of Todd Snider’s shows for decades.

There’s the one about taking life advice from a shoeless, shirtless Slash (yes, the Guns N’ Roses guitarist) at an L.A. bar one morning. There’s another one about trying to buy coffee and a honey bun from a freshly stabbed convenience-store clerk in Midtown Memphis.

For nearly as long as the singer-songwriter has been telling stories, Snider’s been telling audiences that he was going to write them all down one day. Well, he finally did. Snider’s book, I Never Met a Story I Didn’t Like: Mostly True Tall Tales, opens with a caveat that any fan knows already: “Almost everything I say is true. Ask anybody.”

Snider is a hard-core East Nashvillian these days. But when he was 21, he moved to Memphis on a hot tip that he hoped would launch his music career. His dad called him from a Memphis bar. He’d just met the bartender, and she was Memphis singer-songwriter Keith Sykes’ wife’s sister.

“That call was enough to get me to move to Memphis,” Snider writes.

Sykes became his mentor, and Snider found an open-mic night at the Daily Planet. He grew his audience from that Park Avenue bar on songs like “My Generation, Part II.” Snider’s career took off while he lived in Memphis with tours and his record deal with Jimmy Buffett’s Margaritaville Records.

I Never Met a Story I Didn’t Like is not a full autobiography, but that’s not the point. It has detailed versions of Snider’s best-loved stories in chapters called “Jerry Jeff Walker’s Balls,” “Waylon Jennings Sucks,” and “Meeting Bill Elliott.”

Snider fans will love the book. But it’s a fun, wild ride for anyone. — Toby Sells

Gimme Indie Rock: 500 Essential American Underground Rock Albums 1981-1996

By Andrew Earles

Voyageur Press; 400 pp.;

$19.99 (paper)

If you’re a stickler for sub-categorizing every type of music that you listen to into tiny microcosms where only one or two bands fit the exact characteristics of a genre, then Gimme Indie Rock, the new book by local author Andrew Earles, may not be for you.

While Earles might paint with a broad stroke in calling all 500 of the albums he lists as “indie rock,” his research is as thorough as it is impressive. By ignoring the indie vs. major label argument as grounds for inclusion, Earles is able to cover more than 300 bands in this extensive record guide, giving everyone from Nirvana to Sun City Girls the spotlight.

It’s also important to recognize that this isn’t merely a list of the author’s favorite albums. In Gimme Indie Rock, Earles isn’t afraid to admit he isn’t a fan of some of the albums he lists, explaining why the historical or social significance of a band and their work may overshadow how good an album by itself may be.

And no, this isn’t the type of book you’re going to sit down and read cover to cover. But it could definitely help out a newcomer to underground music, and it would certainly come in handy as a back-pocket bible when scouring through used-record bins. By including such major players in underground music like Nirvana and Smashing Pumpkins, Earles makes the book accessible to the most novice of music lovers, and Gimme Indie Rock might be the only book ever to include Nation of Ulysses and Negative Approach on the same page.

The end result is an expansive take on the unsung heroes who have shaped the indie landscape into what it is today. Like many things music-related, most, if not all, of the information in Gimme Indie Rock can be found on the internet with just a few clicks. But like the records that Earles cites, there’s something about holding the product in your hands that makes the experience much more worthwhile. — Chris Shaw

“Literchoor Is My Beat”: A Life of James Laughlin, Publisher of New Directions

By Ian S. MacNiven

Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 560 pp.; $37.50

Early in the 20th century, Ezra Pound had declared to his fellow poets, “Make it new,” and James Laughlin IV, himself a fledgling poet, did. He returned from visiting Pound in Italy to his dorm room at Harvard, where in the middle of the Great Depression, Laughlin founded New Directions, the independent publishing house that brought “advance guard” literature to American readers — but not all American readers. “If you are one of a growing number of cultivated readers … if you resent the commercialism that promotes ‘bestsellers’ at the expense of fine writing and poetry … if you are this kind of reader, the really intelligent reader, New Directions will interest you,” Laughlin announced in the promotional material accompanying his inaugural New Directions in Prose and Poetry from 1936.

Laughlin was banking on a certain audience, who, at the time, had yet to be introduced to the work of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. He was also banking on his own response to the untested literature of his time: new voices in poetry and prose. Those voices, stateside, would come to include Henry Miller, Kenneth Rexroth, Elizabeth Bishop, Thomas Merton, and Tennessee Williams; on the international front, Borges, Garcia Lorca, Neruda, Pasternak, and Dylan Thomas — a who’s who of 20th-century literature. This year we celebrate the centennial of James Laughlin’s birth (he died in 1997) with a biography by Ian S. MacNiven, “Literchoor Is My Beat,” a book that is not only well-researched, it’s a real pleasure to read.

Laughlin could afford to establish what began as a one-man publishing house during the Depression. He came from a prominent Pittsburgh steel family. He received the best schooling, both here and abroad. He read everything. He traveled everywhere. When he wasn’t meeting with and publishing writers he admired, he was skiing the world’s best slopes. And when he wasn’t publishing and skiing, he was meeting women and sometimes marrying them. But he was also a poet who wrote his entire adult life and who late in life finally received the recognition he more than anything sought.

See, then, in addition to “Literchoor Is My Beat,” another new title to go with it: The Collected Poems of James Laughlin: 1935-1997, edited by Peter Glassgold. The publisher of the collected poems is, yes, New Directions. — Leonard Gill

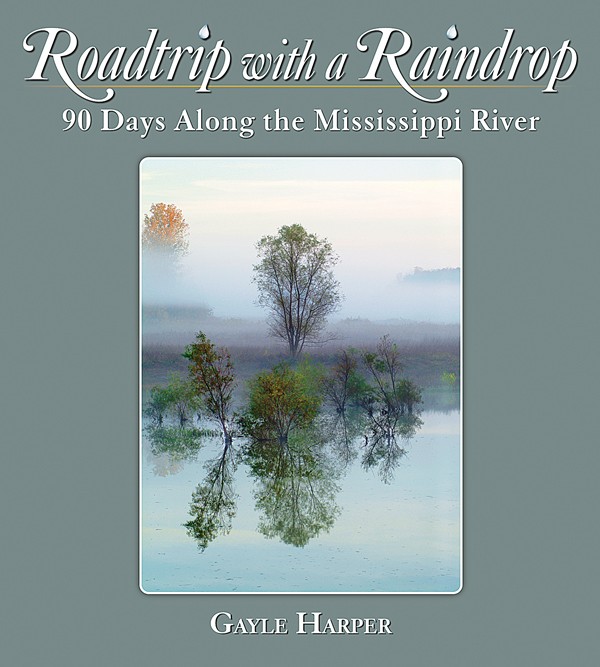

Roadtrip with a Raindrop

By Gayle Harper

Acclaim Press; 236 pp.; $39.95

It’s said that it takes 90 days for a raindrop to travel from the headwaters of the Mississippi on down to the Gulf of Mexico. It took travel writer and photographer Gayle Harper 90 days too — and nearly 2,400 miles driving on and off the Great River Road — to go from Lake Itasca, Minnesota, to Venice, Louisiana. Roadtrip with a Raindrop is Harper’s account of that trip and her photographic record of the people she met, the places she saw, and the river she encountered in all its shapes, sizes, and moods.

This being the Mississippi, Memphis was one of Harper’s stops. A resident of the Missouri Ozarks, she already knew the city pretty well. What she hadn’t counted on was an eye-opening visit with artist Holly Fisher inside the Blacksmith Shop at the Metal Museum and the spirited conversation she had with conservationists Diana Threadgill and Glenn Cox. But it was Harper’s meeting with Joe Royer of Outdoors Inc. that terrified her. That’s because Royer had Harper paddling in his kayak in the middle of the Mississippi. And for once, Harper wasn’t viewing the river from its banks, from a distant vantage point, or from atop one of its gigantic barges. As she writes, “The Mississippi is a mile wide here [at Memphis] and sitting at surface-level, with just inches of boat on either side, brings an exquisite, heart-clutching awareness of its power. … [O]f all the ways that I have been with and on this River, I have never felt such a sublime intimacy with it.”

“Powerful” is the word for many of Harper’s images, from majestic to ghostly, of the Mississippi. Readers of Roadtrip with a Raindrop will to get to know a wonderful cross-section of Americans living alongside the river or working its commercial traffic as well. But more than anything, they’ll get to know Gayle Harper — winning photographer, winning storyteller. — Leonard Gill