History will record 1998 as the year technology demolished the barrier for entry into filmmaking, bringing together high-quality digital cameras and desktop computer editing to enable resourceful would-be directors to bring their visions to fruition. But just because you can make a movie doesn’t mean you can get it to an audience to be seen, so that year, a group of Memphis film geeks put a sheet up on the wall of a downtown bar and projected movies they had made and movies they wanted to see.

A lot has changed since the Indie Memphis Film Festival’s humble beginning. Cameras and editing software have capabilities undreamed of at the turn of the century, rendering celluloid all but obsolete. Home theater and streaming video have opened new avenues for distribution that have theater owners looking over their shoulders and Hollywood studios pushing out bigger and more elaborate spectacles. Indie films still struggle, but now there are thousands of them produced each year, by specialty studios and plucky visionaries with DSLRs. The festival itself has grown from its underground bar-room roots into one of the most respected — and fun — festivals in America. For audiences, the problem has evolved from “How can I find something different to watch?” to “How can I make sense of all these choices?”

That’s where carefully curated festivals like Indie Memphis remain relevant. This year, more than a thousand entries were winnowed down to two dozen competition features, as well as showcases and gala screenings that not only explore the state of the art, but also celebrate classics that have left indelible marks on indie history.

The lineup of narrative features, documentaries, shorts, and experimental videos that will roll out over the four-day weekend at Overton Square venues Playhouse On The Square, Circuit Playhouse, The Hattiloo Theatre, and Malco’s Studio On The Square is among the most diverse in the festival’s history, offering something for every taste. Choosing from such a wide selection of movies can be a daunting task, so we’ll break down your choices by areas of interest to help you explore one of Memphis’ premiere cultural events.

HOME-GROWN

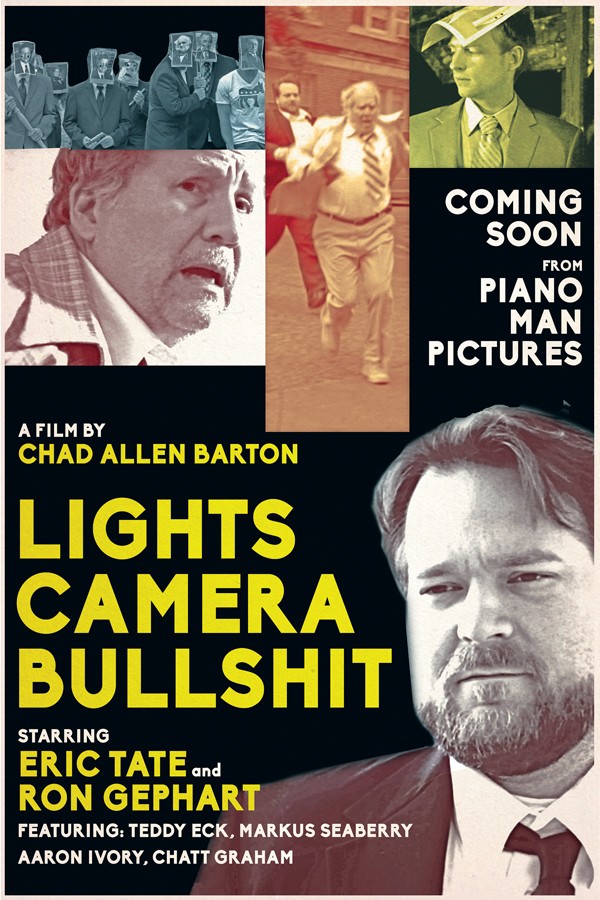

The Bluff City cinema underground looks healthy, as 2014’s crop of local features include both veterans and newcomers. Three narrative features and one documentary will vie for the Hometowner prize.

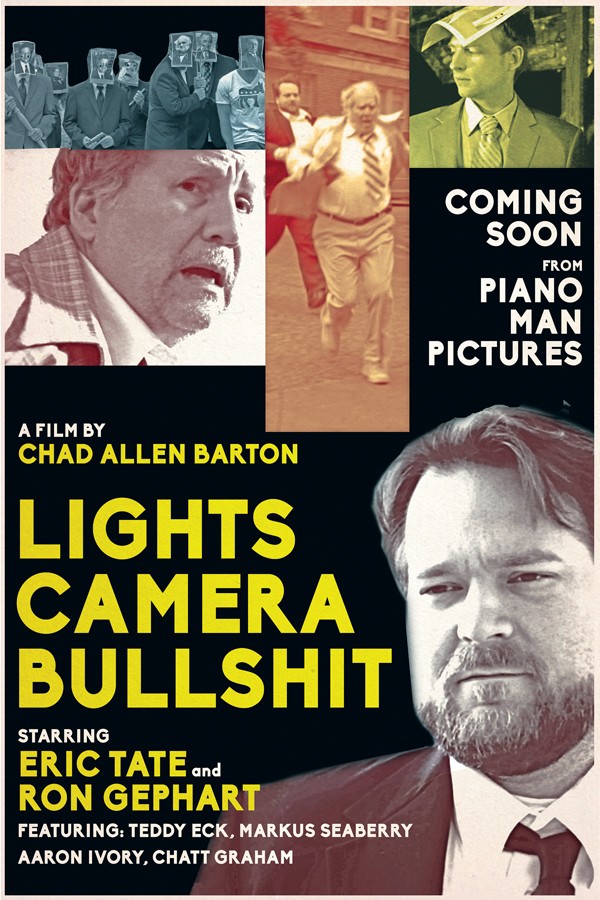

Eric Tate, star of The Poor & Hungry, which launched director Craig Brewer’s career at Indie Memphis in 2000, returns to the screen in Chad Allen Barton’s Lights Camera Bullshit. Tate leads as Gerard Evans, a film school graduate who returns to Memphis to direct art films, but instead finds himself embroiled in a sordid comedy of filmic errors by his unscrupulous boss Don (Ron Gephart). Tate plays straight man to a cast of Memphis indie all-stars, including Markus Seaberry, Don Meyers, Jon W. Sparks, Dorv Armour, Brandon Sams, McTyere Parker, and the late John Still as a terrorist disguised as president William Henry Harrison.

5 Steps to a Conversation

Director Anwar Jamison returns to the festival with his second feature, 5 Steps to a Conversation. Jamison stars as Javen, an easygoing guy who is having a great day until his wife leaves him, saying he needs to grow up and get a job. He signs on with a sleazy, cult-like multi-level marketing company selling free pizza coupons door to door for $20. The film manages to be both funny and affecting (imagine Glengarry Glen Ross as a comedy) featuring strong performances by Jamison, David Caffey, Memphis slam poet Powwah, and 4-year-old Amari Jamison.

Satan (Sylvester Brown) tempts a married couple on the rocks in Just a Measure of Faith, the debut feature of husband/wife team Marlon and Mechelle Wilson. This sincere expression of religious conviction envisions a pair of souls hanging in the balance after a car wreck leaves Jacob (Tramaine Morgan) near death while his wife Kayla (Maranja May-Douglas) is haunted by past sin. It also features stirring musical scenes by gospel singer Euclid Gray.

Director Phoebe Driscoll

Director Phoebe Driscoll’s debut documentary Pharaohs of Memphis traces the history of jookin’, Memphis’ indigenous dance form, from its inception in the 1980s as a way to defuse tense situations on the street to its present as an international sensation, through interviews with the form’s pioneers and its present star, Lil’ Buck. Archival and contemporary footage illuminate the dancers’ athletic beauty.

Rory Culkin in Gabriel

ON THE ROAD

There has never been a film adaptation of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye or Franny and Zooey, but the writer’s disaffected teenage characters drifting through upper-class environs have inspired films like The Graduate and The Royal Tenenbaums. Opening night feature Gabriel takes Salinger’s theme of mental illness upending families to a harrowing extreme. Rory Culkin plays Gabriel, who we meet clutching a much-read letter on a long-distance bus ride. He is searching for a lost love named Alice, whom he wants to marry, but he’s on thin ice with his family. Gabriel’s father killed himself, and they are afraid that he will follow suit, or worse. Culkin turns in a finely tuned performance, carefully crescendoing Gabriel’s encroaching mania as his antipsychotic meds wear off. Director Lou Howe’s pacing is as tight as his visual compositions, and his screenplay is compassionate and affecting, making Gabriel a festival must-see.

Frank Hall Green

Bruce Greenwood and Ella Purnell in WildLike

Frank Hall Green’s WildLike is also the story of a troubled young loner on the road. Mackenzie’s (Ella Purnell) father is dead and her institutionalized mother has sent her to live in Alaska with her uncle (Brian Geraghty), who is sexually abusing her. She runs away during a trip to Denali National Park and lives by her wits until she chances across Rene (Star Trek‘s Bruce Greenwood), a widower who is hiking through the mountains to forget his grief. The pair form an unlikely bond among the sweeping vistas of the Alaskan wilderness as they avoid the pain of their lives. Purnell’s fearless performance is the highlight of this elegant work.

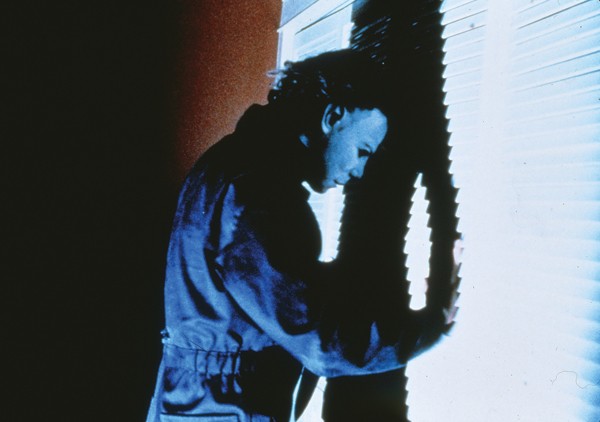

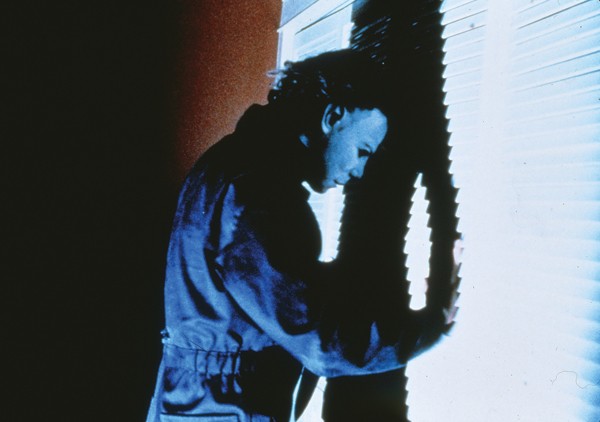

Halloween’s Mike Myers

Halloween

HORROR

Friday night of Indie Memphis weekend is Halloween, and what better way to celebrate than with a midnight screening of the movie that kicked off the slasher genre: John Carpenter’s 1978 Halloween is a textbook of filmic scare tactics. The random jump scare, the relentless menace, redirected sexual guilt — you will never see them done better. Halloween made Jamie Lee Curtis a movie star and set Carpenter on a trajectory that would take the exploitation underground mainstream. If you’ve never seen it or if it’s been a while, the elegance of the film’s construction will make its distant descendants like Saw and Hostel look sloppy and amateurish.

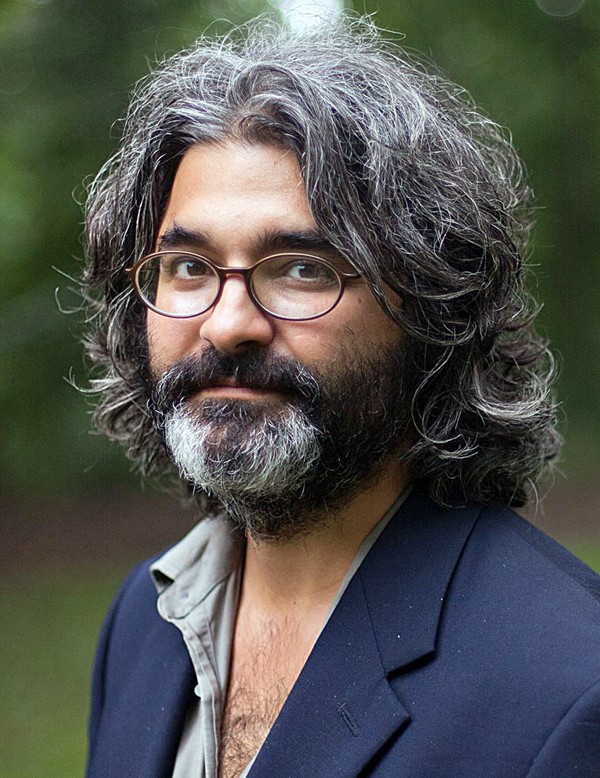

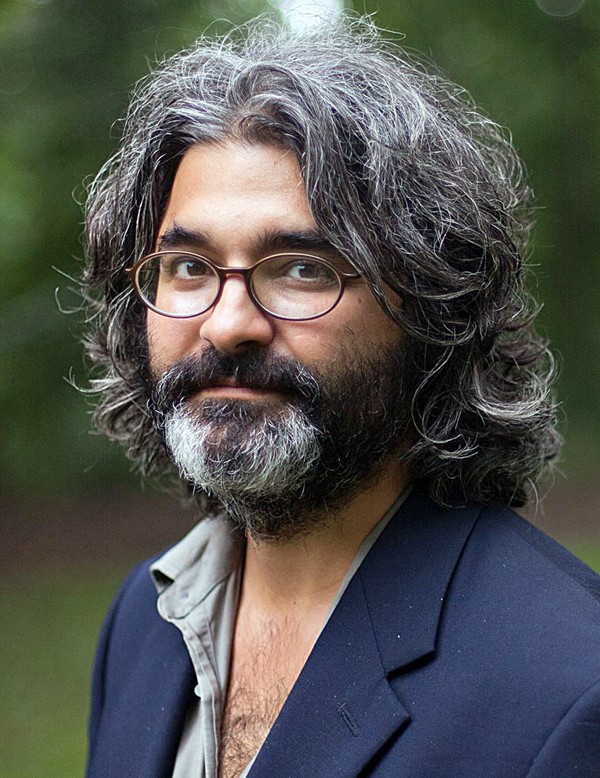

Onur Tukel

On the other side of the horror coin is Onur Tukel’s Summer of Blood. Tukel stars as an obnoxious Brooklyn wannabe hipster who runs across a mysterious stranger in a dark alley and is transformed into a vampire. But just because he’s an undead blood sucker doesn’t mean he’s done trying to score with women, and his vampiric powers make him the chick magnet he’s always wanted to be. Of course, there’s the never-ending thirst for human blood to contend with, but that’s just a minor annoyance in this hilarious deconstruction of both mumblecore pretension and good-guy vampire movies.

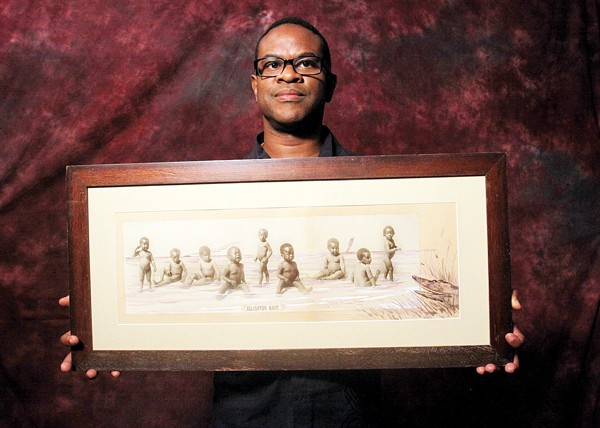

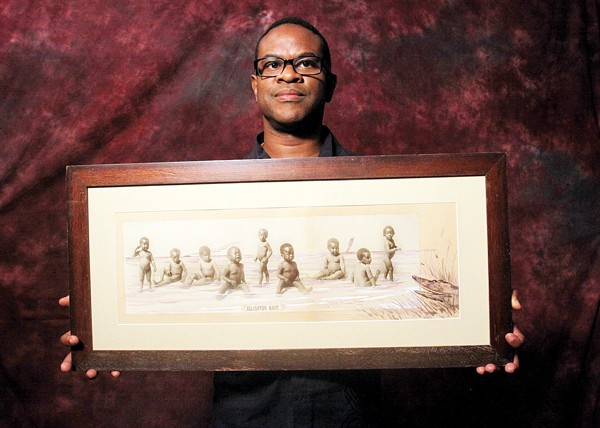

Thomas Allen Harris, director of Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People

An untitled photograph by Lyle Ashton Harris as seen in Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People

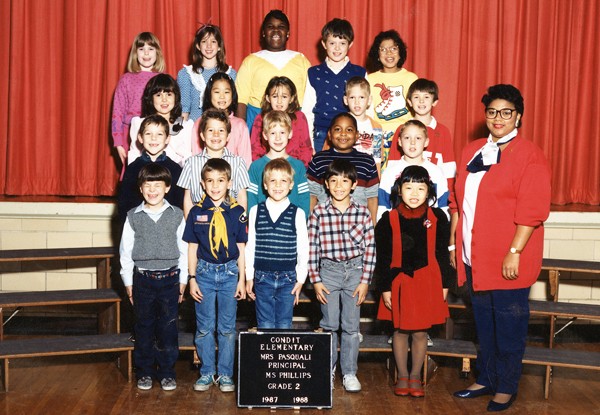

AFRICAN AMERICAN

This is the first year the Hattiloo Theatre will show Indie Memphis films and, appropriately, the festival’s slate of African-American-themed films has never been stronger. In addition to two homegrown narrative features by black directors, a pair of documentaries is worthy of attention. The first is opening night’s Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People. Director Thomas Allen Harris digs deep to find the forgotten and ignored images that African-American photographers made of themselves and their world while America pretended they didn’t exist. These images provide glimpses into the everyday lives of people long dead and who were suffering the persecution of Jim Crow.

Director Lacey Schwartz was raised in a middle-class Jewish household in New York. She had a bat mitvah and went to synagogue and was never treated any differently than anyone else. But when she went to college at Georgetown University, she was forced to confront a secret: Her biological father was African American, and the people she met at school didn’t consider her Jewish. In her documentary Little White Lie, she confronts her dual identities and asks hard questions about society’s assumptions and her own.

Wild Canaries

Lawrence Michael Levine, director of Wild Canaries

CRIME STORIES

Since The Great Train Robbery, filmmakers have turned to transgression as a way to highten stakes for their characters. Brooklyn-based Indie Memphis alum Lawrence Michael Levine tops his acclaimed 2010 Gabi on the Roof in July with Wild Canaries. The comedic take on Rear Window finds Levine and Gabi herself, Sophia Takal, starring as Noah and Barri, a New York couple who suspect their elderly neighbor was murdered by her son. Or maybe as part of a real estate scam. Or maybe she died from old age. Their hilariously incompetent investigation shows very little chance of finding out, until it does.

Man Shot Dead

Director Taylor Feltner

Two documentaries take similar, first-person approaches to examine the ripple effects single criminal acts can have on families — from the perspective of the victims and the perpetrators. In Man Shot Dead Arkansan Taylor Feltner investigates the 1966 murder of his grandfather, Glen Wade Dickson. This real-life Rashomon uses interviews with his family and a search for the only surviving witness to the killing to find meaning, but as the director’s grandmother Bernie says, closure doesn’t come easy, even after 48 years.

Evolution of a Criminal

Director Darius Clark Monroe

Evolution of a Criminal is the story of how director Darius Clark Monroe, a bright, seemingly happy kid, came to rob a bank at age 16. Using interviews with his family, his accomplices, customers in the bank, and the prosecutor, as well as reconstructions of the events, he shows how good intentions soured into bad decisions and the fallout that will haunt him and his family for the rest of their lives.

SCIENCE FICTION

In legendary director John Carpenter’s 1988 They Live, a drifter named Nada (wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper) stumbles across a pair of sunglasses that show him a horrible truth: Earth is controlled by a group of aliens who use subliminal messages in advertising to brainwash the population into compliance with their plans for colonization and genocide. This low-budget exploitation movie sank with barely a ripple upon release, but 25 years of cult adoration and critical reappraisal have recognized it as one of the most brilliant and subversive science-fiction movies ever made. In the brave new world of today’s media landscape, its themes of deception and manipulation are more relevant than ever.

Matt O’Leary in Time Lapse

Two very different time travel movies reveal the sci-fi trope’s versatility. What would you do if you could see the future? That’s the question that Bradley King’s Time Lapse asks. Reminiscent of the tightly plotted puzzle films of Christopher Nolan, the film follows a group of roommates as they find out that their neighbor, an eccentric inventor, has created a camera that sees 24 hours into the future and has pointed it at their apartment. Once they start winning big at the races, their bookie comes sniffing around and their secret puts them all in grave peril.

Alex Boling’s Movement + Location is a more subtle take on time travel. Kim (screenwriter Bodine Boling) is an refugee from the resource-starved 25th century living a peaceful, if confusing, life in New York City with her roommate Amber (an excellent Anna Margaret Hollyman). But things start to unravel when she meets fellow time travelers and they must keep their presence hidden, first from Amber, and then the world of 2014 that can’t know what’s about to happen to it.

MUSIC

Memphis is a music town, and Indie Memphis has always sought out the best music documentaries. Well Now You’re Here, There’s No Way Back is actor/director Regina Russell’s debut documentary, chronicling the rise, fall, and rebirth of 1980s hair metal pioneers Quiet Riot. Singer Kevin DuBrow and drummer Frankie Banali started rocking the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles in the late ’70s, but were virtually ignored in the New Wave-loving ’80s until their cover of Slade’s “Cum On Feel The Noize” unexpectedly topped the charts. After decades of heavy metal decadence, DuBrow OD’d in a Las Vegas apartment in 2007, ending the band. The second half of the film follows Banali (who will be on hand for the screening) as he comes to grips with his friend’s death and tries to stage a comeback.

Director Kenneth Price was a hit at Indie Memphis 2011 with his documentary The Wonder Year, which profiled hip hop producer 9th Wonder. When Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates saw the film, he worked to bring its subject as a class at the Ivy League school. Price’s sequel, The Hip-Hop Fellow, documents the process of 9th Wonder trying to win academic respectability for hip hop, as he creates a curriculum and gives fascinating insights into the origin and evolution of one of America’s most popular music genres. His year-long teaching and research project seeks to deconstruct and research the origins of the samples that went into creating 10 of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time.

For more Memphis-centric music films at Indie Memphis, see our Music section feature, “Soundtrack to Indie Memphis.

…

Heathers

HEATHERS

Cultural phase changes are rarely noticed at the time they happen; only in retrospect do they become obvious. The cynical, slacker 1990s didn’t start with Twin Peaks or “Smells Like Teen Spirit” — it began in1988, with the barely noticed release of a teenage comedy called Heathers.

The 1980s was the decade of Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America,” where we collectively decided to put on a happy face and let the wealth trickle down. The movies of the decade were escapist science fiction epics, He-Man action, and angsty teen coming-of-age movies that said we could all resolve our differences and just get along. Then the caustic, gonzo Heathers flipped the table.

Great satire always predicts the future. Just as Network predicted Fox News way back in 1976, Heathers predicted school shootings and the cynical exploitation of public opinion that would follow. Winona Ryder and Christian Slater star as a teenage Bonnie and Clyde who upend the social pecking order at Westerburg High School by killing some of their frenemies and staging them as suicides. Memphian Shannen Doherty is one of the titular mean girls.

The film remains blazingly funny on its 25th anniversary. Its whip-smart dialogue wrings laughs out of the horror, and gave Generation X the tools to laugh off the world’s casual cruelties. Director Michael Lehmann and writer Daniel Waters will be on hand at the Indie Memphis screening for what is sure to be a spirited and hilarious discussion of the film’s creation and legacy.

…

American Cheerleader directors David Barba (left) and James Pellerito (right)

SPORTS

For sports fans, the can’t-miss film at Indie Memphis is Hoop Dreams, the 1994 epic that launched a thousand 30 for 30 episodes. On the short list of the best documentaries ever produced, it tells the story of Arthur Agee and William Gates, two high school basketball players trying to make it to the big leagues, and who will reunite at this 20th anniversary celebration.

American Cheerleader is as optimistic as sports documentaries get. The practice footage and interview segments argue that competitive cheerleading empowers girls by transforming them from walking sexist clichés into skilled practitioners of a very difficult, very dangerous prep sport. It follows the two-time defending champions from New Jersey’s Burlington Township High School, as well as the up-and-comers from Kentucky’s Southwest High. You may develop a rooting interest as the final round begins, but tiresome good vs. evil conflicts seldom appear.

In contrast, Amir Bar-Lev’s ambitious, disturbing Happy Valley, which looks at the sexual-abuse scandal involving Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky and its impact on the residents of State College, Pennsylavania, is a headfirst dive into a mine shaft flooded with subterranean prejudices, moldering messiah complexes, and cracked, sunken chunks of community pride. In archival footage, Penn State football coach and unofficial town paterfamilias Joe Paterno comes across as an eminently sensible public servant who once called football “a silly game.” But Paterno set his moral high ground ablaze when he swept Sandusky’s abuse under the rug. As Happy Valley shows, the repercussions from his actions are still visible as statues and murals become public battlegrounds, and community residents turn over media vans in protest. The film is complex enough to dredge up tons of issues and sure to leave interested parties waiting more. — Addison Engleking

…

SHORTS

There is no better way to sample the endless variety of perspectives film festivals have to offer than the shorts programs. The key is to stumble upon as many contradictory things as possible.

The Hometowner Narrative Shorts program presents a sampler of Memphis talent on Friday night. One unifying theme in the varied program is violence, usually with a gun drawn for either comedic or dramatic effect. In Robert Rowan’s Friendly Faces, two gleeful idiots laugh maniacally at each other for long periods and attack someone on a basketball court for no reason. The block is chock full of familiar faces behind and in front of the camera: For example, Don Meyers, the aforementioned basketball court victim, also directs Fade To Black, a short about Parkinson’s disease dedicated to his father. On the other end of the spectrum, Adam Remsen’s Quicken celebrates the joy of new life.

Elsewhere, an office worker fails beautifully in Lights Camera Bullshit lead actor Eric Tate’s hallucinatory, darkly humorous directorial debut Default Settings. A young woman teeters on the edge of madness in Laura Jean Hocking’s experimental Two Whole Days of Nothing But Uppercase “F*CK.”

Shane Watson’s documentary Untold Stories focuses on Trayvon Martin and other recent cases of unarmed black shooting victims. It shares with other Memphis docs a philosophical inquiry about the nature of civic life and an appeal to change it. Emily Heine’s No One Sees You asks why public, non-moneyed art on walls is illegal. Lara Johnson’s Geekland: Fan Culture in Memphis shines light on our pop culture outcasts.

The music documentaries likewise have a kind of a direct, barebones emphasis on their subjects, from Matt Isbell making guitars in Once There Was a Cigar Box to multi-instrumentalist Sean Murphy making haunting sounds in Sketches of Crosstown. The eulogy Jim Dickinson: The Man Behind the Console, is bookended with simple old images of a performance at Otherlands.

The best of the non-local shorts is Buffalo Juggalos by Scott Cummings, a dry, ironic provocation consisting of brief portraits of Insane Clown Posse fans. At first the shots are naturalistic, on front lawns, with babies and pet ferrets. But slowly, it becomes more and more exploitative until the movie resorts to fake crime, simulated sex, and an explosion. It is queasy, and yet often the images add up to a celebration of grassroots art. — Ben Siler

…

Sophie Traub in Thou Wast Mild and Lovely

ARTHOUSE

Joy Kevin is a closely-cropped portrait of a financially strapped New York couple whose life together butts up against age-old difficulties of money, boredom, and wandering attention, but whose solutions are never predictable. The simple subject allows the film to meander gracefully through Kevin’s (Jordan Clifford) mumbled, joking evasions, and Joy’s (Tallie Medel) dancer’s charisma.

The movie is light as a feather but stiff as a board. Kevin, an aspiring comedian, is a kind of post-feminist Woody Allen. Joy is tough, a real estate agent by day and experimental dancer/choreographer by night, forced to be in control even as she badly needs to be vulnerable. It is in this generationally familiar lightness, and the final failure of the film’s smooth, joking likability, that Joy Kevin achieves gravitas.

In Josephine Decker’s Thou Wast Mild and Lovely Akin (Joe Swanberg), a married school teacher, takes farmhand work for the summer on Jeremiah’s (Robert Longstreet) homestead, where he becomes sexually obsessed with Jeremiah’s adult daughter, Sarah (Sophie Traub). Akin’s obsession is twisted into the unhealthy (but never explained) dynamic between father and daughter, and metered with the quiet cruelty of farm life. Flies swarm a cow, the blood from a chicken stain’s Sarah’s dress, and Akin dreams of Sarah suspended by ropes in a red barn. The unslept tension that drives the movie is realized through sharp sound editing and Terrence Malick-inspired cinematography.

There is no shortage of media about teen pregnancy, whether cool and controversial or tough and possibly romantic. In Nathan Silver’s Uncertain Terms, teen pregnancy is none of these. Instead, it serves as a backdrop for the slow gestation of Robbie’s (David Dahlbom) marital troubles when he takes up residence as a handyman at a boarding house for knocked-up girls. There, he becomes infatuated with the somehow virginal Nina (India Menuez), who, despite her advanced pregnancy and serious relationship with a ne’er-do-well boyfriend, dresses in flowing white and floats detachedly around the house. Desperate to escape the growing complexities of their respective situations, Nina and Robbie bond quickly. Uncertain Terms, like The Virgin Suicides, is a portrait of girlhood-becoming-womanhood as experienced by a misled man who, despite his attempts to find meaning for himself in the power of the girls’ situations, remains a hopeless outsider. — Eileen Townsend

…

Whiplash

Whiplash

WHIPLASH

As Terence Fletcher, the black-clad music instructor at the center of writer-director Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash, J.K. Simmons is a compact, muscular demon, unfettered by the rules of teaching, etiquette, and human decency. Sometimes Chazelle uses shadows or offscreen sound to foreshadow Fletcher’s arrival, but most of the time he simply bursts into a scene, and the effect is as jarring as a smoke alarm going off. Fletcher’s pupils are terrified of him; they look down whenever his head looms above them like a menacing moon. But young drummer Andrew Neyman (Miles Teller), a student at the New York conservatory where Fletcher “teaches,” wants to play in his studio band. Yet once Andrew gets his big break, it’s tough to fathom why he stays. The physical and psychological abuse he absorbs leaves him doubting whether he’ll ever become anything at all, much less the next Charlie Parker.

Chazelle’s aggressive, up-tempo account of Fletcher and Andrew’s evolving relationship follows loose and shifty rhythmic lines. It charges along like Buddy Rich, then plays around with the beat like Elvin Jones. The result is an uneven, slightly overlong affair that nonetheless yields several rich, well-measured scenes: a dinner-table pissing contest between Andrew and his brothers; a pair of quiet romantic interludes with Andrew and his girlfriend (Melissa Benoist); and a highly contrived yet deeply affecting (and profoundly ambiguous) musical finale.

As a movie about teachers and education, Whiplash is as phony and false as Dead Poets Society. But as an expressionist riff on the price of artistic greatness, it’s thoughtful, exciting, and difficult to shake. — Addison Engelking