Many of the most memorable Memphians are transplants from other cities. Consider famed composer W.C. Handy, born in Florence, Alabama, who notated the Memphis blues. Grizzlies star Ja Morant, who most fans agree embodies the spirit and soul of the city, is from South Carolina, not Tennessee.

Maybe it’s something about choosing Memphis, recognizing the magic here, that helps newly minted Memphians find the frequency of this musical place. Maybe it’s simply that living elsewhere grants perspective, and thus a deeper discernment. If that’s so, it would go a long way to explaining poet and author Tara M. Stringfellow’s uncanny understanding of the Bluff City.

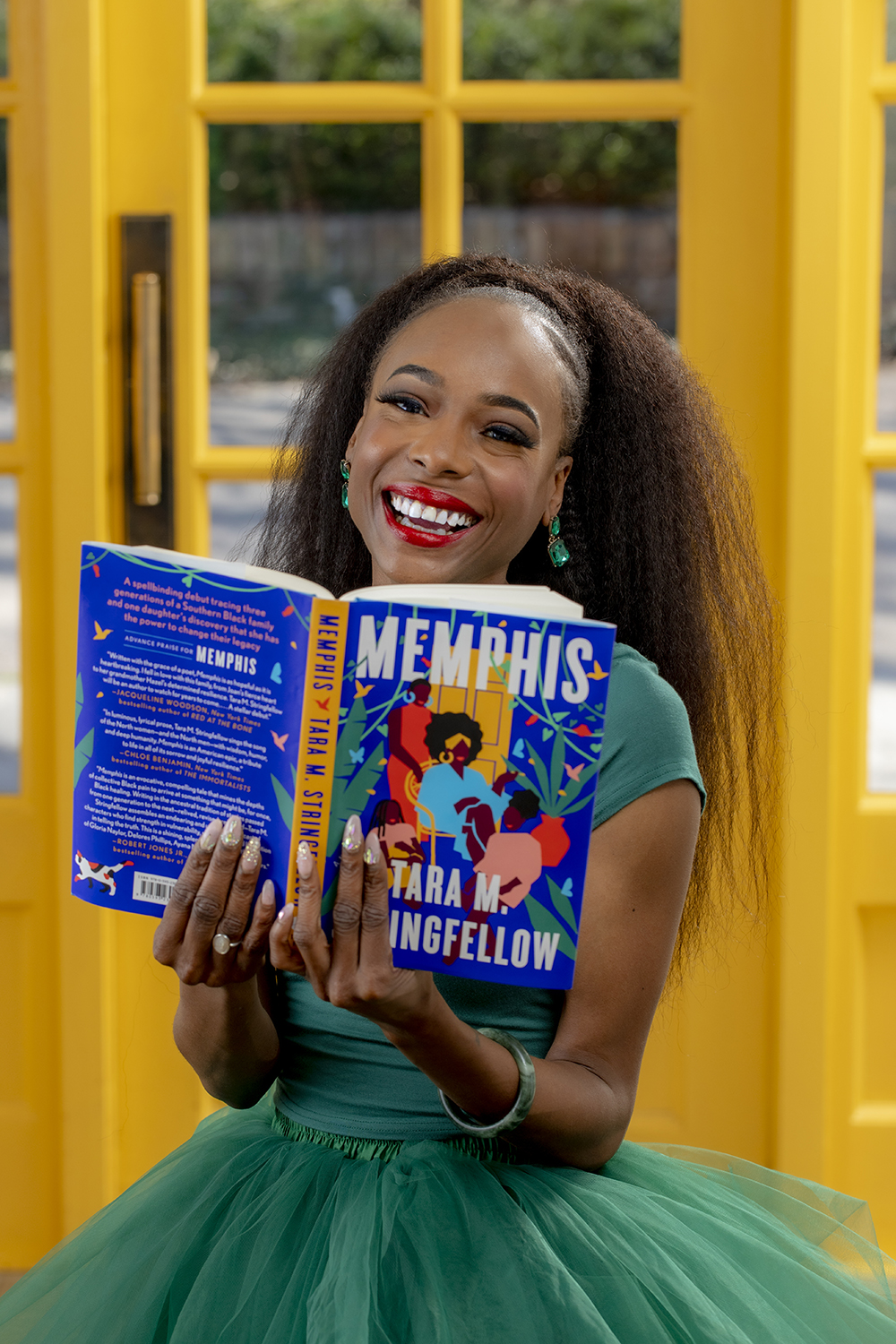

Stringfellow, whose debut novel Memphis (The Dial Press) was released in April to rave reviews (The New York Times called it “rhapsodic”), is a Memphian. But she hasn’t always been. Though her family has deep roots in the city from which her novel takes its name, Stringfellow grew up on a military base in Japan before moving to Memphis when she was a child. She has also lived in Ghana, Chicago, Cuba, Spain, Italy, and Washington, D.C., before settling in Memphis (again) as an adult. Perhaps serendipitously, she finished her novel, during the coronavirus pandemic, in Memphis.

Her debut evokes the history of her new home. Memphis is the story of three generations of Black women in Memphis. It follows young Joan, her sister, her mother and aunt, and her grandmother over the course of 70 years. It is a story both tragic and triumphant, a family saga that charts its way through the turbulent waters of racism and violence and complicated relationships, but ultimately toward forgiveness, growth, and the power of hope, art, and community.

In the novel, Joan’s grandfather built a house in the historic Black neighborhood of Douglass — only to be lynched days after becoming the first Black detective in the city. That loss echoes through generations. So too does the kindness of the Douglass community, the power of painter Joan’s art, and the ways a family can leave a legacy, all brilliantly evoked in Stringfellow’s lyrical prose.

Local bookseller Becca Sloan calls Memphis “an exquisite take on Memphis over the years, a celebration of Douglass, an ode to Black womanhood, to community, to identity, sisterhood, strength.”

Nicole Yasinsky, marketing manager at Novel bookstore, says, “Tara Stringfellow’s poet origins shine through in her lush descriptions of everyday things, and her characters are ones that will stick with me forever. She manages to guide us through generations of trauma and pain while also highlighting the beauty, joy, and resilience of her characters and this city. We were thrilled to host Tara at Novel for her book launch party — to a sold-out crowd — and sales and love for the book continue to grow. Almost every day, I see someone discovering Memphis and Tara Stringfellow for the first time, and I feel certain she has a long and brilliant career ahead of her.”

A Poet’s Beginnings

Setting is key, in fiction and in life. Just as Stringfellow’s novel is inspired by family history, her life as a writer was nourished both by her Memphis roots and her time spent abroad. “Memphis has always been my ancestral home,” she says. “I’ve been coming here in the summer since I was a little girl, but I mainly grew up in Okinawa, Japan. I spent my formative years there, my childhood there. That’s probably the reason I became a poet. It’s a beautiful, beautiful place. Living on a tropical island, learning how to swim in the sea, eating noodles, and watching anime is going to make somebody a little weird. What was I supposed to become except a poet?”

Her father is a retired marine and is now a congressional liaison. He was an officer in Japan, and Stringfellow’s childhood experiences there gave her perspective. She says she didn’t experience racism there as a young Black child, at least not in the way she does in America. “I can’t tell you how valuable, how privileged that is,” she says.

After her father read her a poem when she was only 3 years old, she knew she wanted to be a poet, so she dedicated herself to writing and a love of poetry. The push and pull of her life on a tropical island and her roots back in the States helped her develop her voice. She grew up “always knowing that I was from Memphis, and calling back to my folks in Memphis,” she remembers. “Long-distance calls from Okinawa to Memphis … It was kind of the perfect confluence of events.”

Eventually, Stringfellow’s family left Japan, moving back to the U.S. Later, after her parents’ divorce, Stringfellow remembers, “We moved cross country in a van.”

With her mother, she moved to her great-aunt’s house in North Memphis, a time and place that would inspire settings in her novel. “Douglass kind of raised me for a bit,” Stringfellow says, “and I loved it.”

The Road to Memphis

Travel is an undeniable part of Stringfellow’s story, both her true life’s tale and the plot of her novel. “I believe wholeheartedly in it. I do. I know I say this from a rather privileged position, but even when I was dirt-poor teaching English at White Station, I saved my pennies all year, so I could live abroad in Cuba, in Italy,” Stringfellow says, adding that the experience was “awakening for me as a writer.”

Long before she (with her faithful hound, Huckleberry) settled in Memphis, Stringfellow was on her way, paving the road to Memphis. She lived for a time in Chicago, a city with ties to the Bluff City. There she worked on her poetry, following the compass of her artistic ambition. “I would do a lot of spoken word events, a lot of poetry readings. Chicago’s great for that,” she says. “I loved it. I just knew I wanted to do this, so I would just do odd jobs.”

While odd jobs can help make ends meet, even poets sometimes long for a little stability and security. “I said, ‘Oh, I have to eat food. And that costs money,’” Stringfellow remembers. “I went to law school. It’s something I did, but I didn’t really want to be an attorney.”

Practicing law is often lauded as the perfect post-graduate profession for those who excelled at writing in their undergraduate years. But even if one has a talent for it, if their heart is pulled, like a lodestone, naturally magnetized, toward a different horizon, then all the success in the world counts for little. “I was just this poet who would show up and say, ‘Well, I’m here because my poetry didn’t sell,’” Stringfellow laughs, adding, “People would just look at me like ‘You’re not here to hustle and be a Supreme Court judge?’” She was as smart and ambitious as any of her peers, but her ambitions would lead her down a different path, on the winding road back toward Memphis.

Stringfellow graduated and became an attorney. She got married and eventually got divorced. Each change took courage. How many great novels are never finished because the author-to-be fears to leave a sure thing and strike out into the unknown? “I gave it all up. I got divorced,” Stringfellow remembers. “I went back to Northwestern at night to their MFA program, which was not fully funded. I paid for it out of pocket,” she says, “and I wrote. On a wing of a prayer.” But her faith in herself paid dividends. She kept writing, and she met with an agent. “I said I had a book,” she says. “I just knew I had a hit. I was like, ‘No, I’ve been preparing for this my whole life. This is destiny and faith.’ So I became dirt-poor and invested in myself, and my parents understood.”

It’s clear that her family means much to Stringfellow; she mentions her mother and father frequently in our conversation. “I’m already blessed because most parents, I don’t think, would say that to their children,” she says. “People say life is short, but life is long when you make the wrong decision.”

So, as she wrote her way toward a publishing contract, Stringfellow kept her faith. Meanwhile, the world was in turmoil — political instability, one of the largest social justice movements in U.S. history, and a global pandemic made the backdrop as she continued to believe in the future she envisioned. “We all thought like, ‘Lord, what’s gonna happen?’ I had a book deal, but we didn’t sign the contract for months.”

Still, she says, there was comfort in drawing the story inside her out into the world. At the time, she lived with her father, a poet and her first reader, sharing her vision for her novel with him.

“I had no idea I would get this book deal. During my life, I didn’t think anyone would want to read a story about Black women in a house in Memphis. I thought maybe somewhere a small publisher would take a chance on me and maybe it would strike big, but maybe not,” she says. “I was ready and willing to give my life to the canon anyway. And to teach and maybe get a poem in a magazine.

“I didn’t do it for the fame at all. This is very shocking.”

The Book of the Bluff City

“Memphis, we’ve just been through a lot,” Stringfellow says. “I really wanted to do something nice for us. People kind of forget about us, or they get famous and leave. I still live here. I live in North Memphis in a Black historic neighborhood. I want to live here until the day I die.”

The author talks of writing her novel while former President Trump made public comments “disparaging Black cities across this nation,” she says, referencing Trump’s vile remarks about Baltimore. “I was sick of that. Just because we’re poor and because there’s a lot of crime here doesn’t mean that we’re not beautiful people and worthy of high art. Memphis is the best city on Earth. I have lived everywhere. I don’t know of another place on this Earth that is so welcoming and warm.”

So she wrote something for Memphians to be proud of, to see themselves reflected in, with honesty and love. “I certainly did write it as a gift for Black women,” Stringfellow says. And she wrote for her family. “You owe it to your grandfather, who you’ve never met. You owe it to your grandmother who died way too young,” she remembers telling herself. “I’m just trying to write and write as well as I can.”

To do so, Stringfellow brings all her skills to the task. She has a keen ear for language, and a poet’s gift for word choice. “You can tell a story in fiction with the poetic tools,” she explains.

She says that when she envisions the scenes, she can hear her characters speak, note the differences of their accents. It’s telling that she mentions accents, as they are mentioned often in the novel; they give subtle shades of characterization. Stringfellow understands the social, economic, and geographic forces at play in the region, the difference between rural Mississippi and rural Tennessee, and how these forces converge on Memphis.

As we speak, she often talks of meter, of the sound and rhythm of words. She considers her artistic choices carefully; Stringfellow is as elegant and nuanced a writer as has ever walked the streets of the South, a region known for its talented storytellers. She has put in the work, read and listened, traveled and studied. She’s worn many titles, written across genres, and each new challenge has honed her skill, deepened her understanding of how words can evoke an emotion. She would need all those tools to tell the story of Memphis, one both emblematic of the region and profoundly personal.

Poets Are Political

It’s impossible to unspool the story of Memphis without acknowledging tragedy, and the overwhelming tragedy of the United States is its history of racism and oppression. Memphis is a city of small, tight-knit communities, where great strides were made toward equality and civil rights, and where just as much pain has been inflicted. For Stringfellow, some of that pain is undeniably personal.

“Growing up, I knew my grandfather was the first Black homicide detective in Memphis, but the circumstances of his death were as murky as the banks of the Mississippi from which his body was pulled,” she writes on her website. “I grew up with devastating, grief-laced stories about gorgeous and unknown Black folk. All I had as proof were quilts and stories. But I knew, intrinsically, that it would be my lifelong duty, like my mother in our kitchen, to make those tales sing.”

In this, Stringfellow’s passion is a vocation, a calling. She wields her words with responsibility, one made urgent by this sad truth: History repeats itself.

“When I was writing about the death of Myron, based on my actual grandfather,” she remembers, “George Floyd died that same day. … I’m sitting there writing the chapter in my daddy’s basement. That’s when I knew I had to dedicate the book to his daughter.” Stringfellow did just that, and wrote Gianna Floyd a poem as well. “Who’s gonna read this girl stories at night now? That’s a dad’s job,” she remembers thinking.

“I just felt like I was so angry. I needed a whole book to write instead of a poem,” Stringfellow says. “When people take Black men from this world, I don’t think they realize who and what kind of village they’re taking every time. I wouldn’t be the poet I am if I didn’t have my dad editing my work.” That reality is embedded deep within Memphis. Each loss is felt, not just once, but again and again throughout the years. Each trauma creates ripples that touch and distort many more lives.

The poet says it was vital for her to tell the truth, to call out injustice. “Poets are political. We reflect the time, like the news criers. I had to reflect what I see around me,” she explains. “My mom had to grow up without a father. Like, that’s a real thing.”

Stringfellow does more than illustrate the ills of our age, though; she also uses her novel to inspire. One message woven into the fabric of Memphis is this: Art is powerful, and it strives to stitch a community together, to be a catalyst for change. The message is seen throughout the novel, especially through Joan’s paintings. It’s something Stringfellow holds dear as well. Of art, she says, “It should make you cry. It should make you uncomfortable. It should bring up memories.

“It should spur you into some sort of action on your own path, to ask larger questions of yourself, as a human being on this Earth, what are you doing? And are you doing it well, are you doing it with love? If art doesn’t do that, then what’s the point?”