Tennessee Republicans want to start killing the state’s death row inmates again, enough so they want to bring in firing squads and “hanging by a tree.”

Executions in Tennessee are now halted, hamstrung on scientific protocols for lethal injections. An execution set to go ahead last year came nail-bitingly close before the governor issued a last-minute reprieve. When the truth finally surfaced, state officials admitted they did not follow their own rules to safely carry out the execution (and others).

Governor Bill Lee wanted to know why. The report he ordered came back right before Christmas. And it was hot. The findings were big enough and bad enough to halt all executions — including those by electrocution — in the state and to see two top officials fired. It also put the Tennessee process for lethal injections under review and repair.

While that method is on hold, GOP members of the Tennessee General Assembly have spent part of this year’s session casting about for alternatives. Both the firing squad and hanging methods of execution they’ve suggested made headlines this session. The “hanging” notion never really received any serious consideration and came with a rare GOP apology on its harshness. Even though the firing squad idea seems harsh, too, that idea gained serious traction and continued to move through the Senate committee system as late as last week.

Another GOP bill sought transparency in the lethal injection system, making public the names of the companies that make Tennessee’s lethal injection drugs. Those names are now confidential via a special request by the Tennessee Department of Correction (TDOC) a few years ago.

Lawmakers don’t often champion government transparency, especially when private companies are in the mix. And with this bill, transparency seemed secondary. The bill sponsor said if his bill could help fix the execution system, then executions could continue, hopefully without hiccups like last year’s that made victims’ families “wait for their day of justice to come.”

Attitudes on the death penalty in general were expectedly divided during the session. Many Democrats lambasted the method as inhumane and questioned GOP bill-carriers to see if they felt the same way at all. They didn’t. They said so. Further, some even said they didn’t care if an inmate felt pain while they were being executed.

Most of the Republican discussion on the bills focused on the cogs and wheels the state needed to adjust in order to get its death penalty process back in working order. However, lawmakers in some of those talks found dark places, sometimes describing macabre scenes as they plumbed the itchy intrigue of execution’s nitty-gritty.

For now, though, the future of state-conducted death is unclear in Tennessee. Lee’s administration works in the background to get the lethal injection process in line and on line. In the foreground, GOP lawmakers push for new ways to get it done. On death row, inmates live another uncertain day.

“Sorry, I didn’t have it tested.”

The man asked for a double bacon cheeseburger, deep-dish apple pie, and vanilla bean ice cream. TDOC issued a statement on it.

This was April 20, 2022. Death row inmate Oscar Franklin Smith’s time had come. The Tennessee Supreme Court originally set his execution date for June 2020. Court motions by his lawyers set the date back one year to February 2021. That execution was stayed as Covid paused all executions in the state. When the pandemic suspension lifted in 2022, the warden at Riverbend Maximum Security Prison, home to Tennessee’s death row, was to alert Smith by April 7th that he had two weeks to live.

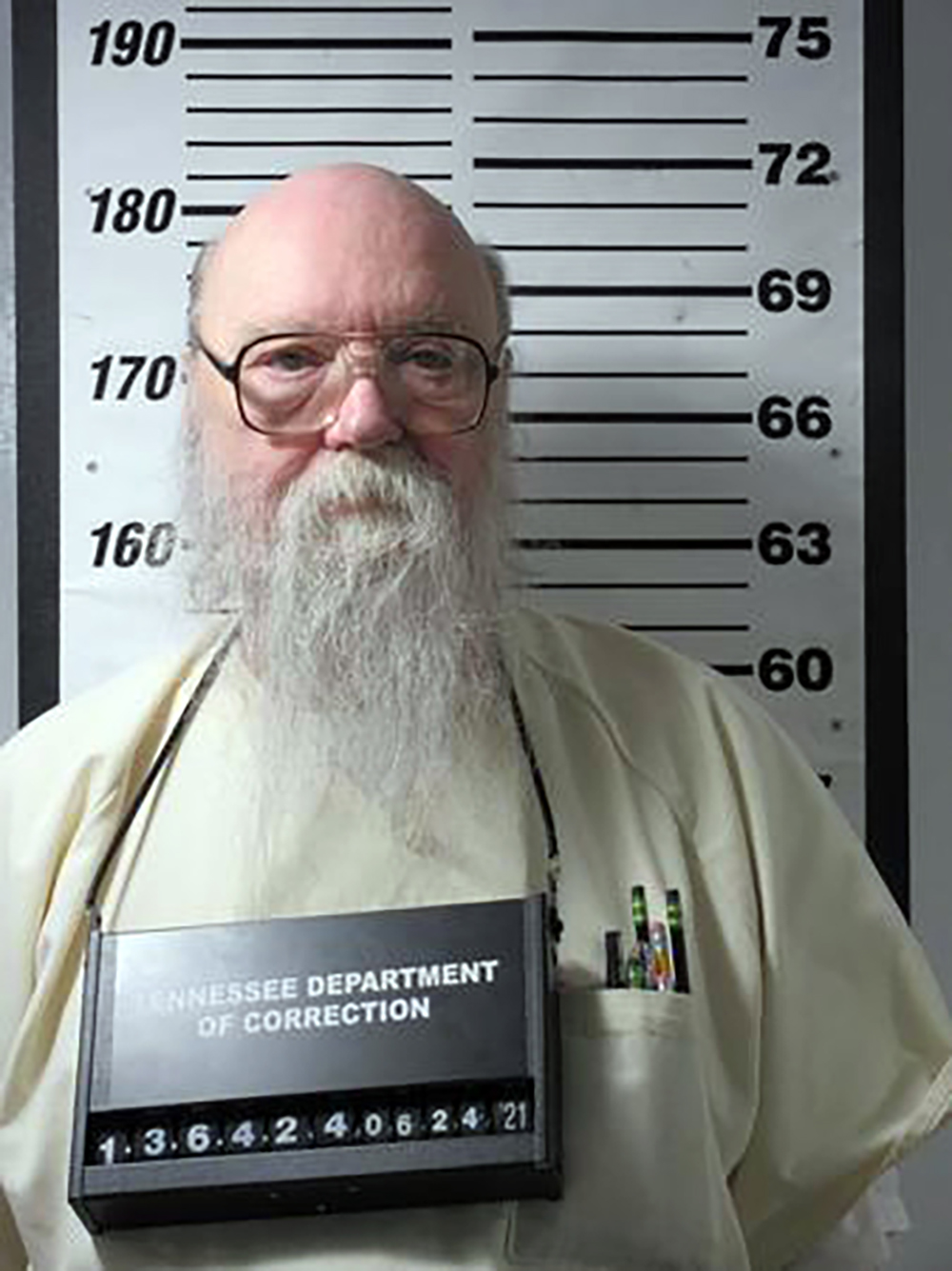

Smith, 73, was and is the oldest person on Tennessee’s death row. A recent mugshot shows it. He’s bald with shop-teacher glasses and a white beard that flows over pens and pencils in his shirt pocket to his chest.

In 1989, officials say Smith murdered his estranged wife, Judy Robirds Smith, and her two sons, Chad and Jason, who were 13 and 16 at the time. According to accounts from The Tennesseean, Judy was shot in the neck and stabbed several times. Chad was shot in the left eye, upper chest, and left torso. Jason was stabbed in the neck and abdomen.

A 911 call from the night was presented at trial. In it, the boys are heard crying out, “Frank, no! God help me!” A bloody handprint, identified as Smith’s, was found on the bedsheet next to his wife’s body, according to The Tennessean.

Smith was convicted of the murders in 1990. He’s been in state custody for 32 years.

Smith was moved to death watch last year at 11:50 p.m., April 18th, a Monday. He’d spend the next three days under constant surveillance in a cell adjacent to the execution chamber. On Thursday at 4:12 p.m., he was given his last meal — the burger, pie, and ice cream. A statement from the state said he received it but did not say if he ate it.

The lethal injection chemicals made for his execution had arrived at Riverbend the previous week, according to the report Lee ordered last year. That week, TDOC officials trained for the execution. On April 20th, a Wednesday, the lethal injection chemicals for Smith were moved to a refrigerator to thaw.

That day, Smith’s attorney, veteran death penalty lawyer Kelley Henry, asked TDOC if the chemicals had been tested for “strength, sterility, stability, potency, and presence of endotoxins” and requested a copy of the results. These tests are mandatory by rules established by Tennessee lawmakers in 2018 to ensure safe executions. The tests are important to ensure the drugs were manufactured correctly and because endotoxins can cause fever, septic shock, organ failure, or death.

TDOC asked the “drug procurer” (the name kept secret under state law) about the tests who, in turn, asked the “pharmacist.”

“No endotoxin test, it’s a different test but based on [federal pharmacy laws] the amount we make isn’t required,” they texted in response. “Is the endotoxin test requested? Sorry, I didn’t have it tested.”

With this, the governor’s report says, “at least one TDOC employee was aware that no endotoxin testing had been conducted on the drugs on the day before Smith’s execution.”

The next morning began with more text messages between the state and the pharmacy.

“Does [redacted] still have the samples?” read one text. “Could they do an endotoxin test this morning/today?”

“Honestly doubt it,” the pharmacy replied. “I would’ve had to send extra product for them to test it.”

The TDOC team readied for the execution — set for 7 p.m. — amid ongoing discussions about the testing between its office, Lee’s office, and the Tennessee Attorney General’s Office. If the drugs had not been tested for endotoxins, TDOC would have to ask Lee for a reprieve.

At a 1:30 p.m. meeting, the pharmacist said chemicals for Smith’s execution were not tested for endotoxins. The procurer called it an “oversight.” With this, TDOC and the AG recommended the reprieve.

While a decision was being made, everything for the execution was still in motion. The TDOC staff were taking their places for the execution. The victims’ families and the media were being moved to the facility. At 4:30 p.m., the drug procurer and executioner removed the chemicals from the refrigerator and moved it to the execution chamber. At 5:30 p.m., the execution team prepared the syringes.

At 5:45 p.m., TDOC learned the governor would issue a reprieve. And then the warden told Smith. Setup for the execution was halted at 5:51 p.m. with work partially complete on the first drug.

“We are preserving everything,” reads a TDOC text from 6:36 p.m. “So don’t throw anything away or alter any stuff.”

The next day, the pharmacist said drugs used in two previous TDOC executions (Donnie Edward Johnson and Billy Ray Irick) had not been tested for endotoxins and they had never been asked to test for them. The pharmacist did not know that such testing was even part of Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol and investigators said a copy of the protocols had never been given to them.

On May 2nd, Lee announced a halt on all executions and hired former U.S. Attorney Ed Stanton to conduct a third-party review of Tennessee’s execution process.

“TDOC leadership placed an inordinate amount of responsibility on the Drug Procurer without providing much, if any, guidance, help, or assistance,” reads the report. “Instead, TDOC leadership viewed the lethal injection process through a tunnel-vision, result-oriented lens rather than provide the necessary guidance and counsel to ensure that Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol was thorough, consistent, and followed.”

In December — the day before the report became public — Lee fired Debbie Inglis, TDOC’s deputy commissioner and general counsel, and Kelly Young, the inspector general, in connection with the report’s findings. In January 2023, Lee picked Frank Strada to lead the department. Many believed Strada was hired to fix the execution system after he’d helped Arizona restart its program after an eight-year pause.

“That is not cool.”

Three weeks into the Tennessee General Assembly’s current session, bills were filed in the House and Senate giving the state’s death row inmates a new option for execution. A firing squad “just simply gives them that option,” according to Rep. Dennis Powers (R-Jacksboro), the bill’s sponsor.

During his many appearances before committees to explain and defend his bill, Powers has maintained that a firing-squad death is the “most humane and most effective way to do it,” with “it” apparently meaning to kill a Tennessee death row inmate. He says, according to a survey (that he has never shown in committee meetings), inmates prefer the firing squad.

When pressed on whether or not Tennessee should use the death penalty, Powers would fall back to a three-pronged argument: Capital punishment is legal in Tennessee, it’s not unconstitutional, and neither is his bill. He then leans in on the fact that executions are halted because of all the troubles given in Tennessee’s lethal injection protocols.

In the hearings, Powers was seemingly straightforward on the fact that killing a prisoner with a firing squad isn’t a harsh, outmoded (or even edgy-cool) method of execution. It is “not like the old Westerns when they stand up and put … a blindfold on and they’re standing there and they give them a cigarette or something.”

Other lawmakers listened thoughtfully to Powers’ rationale. Then, they’d give in to their curiosity. How would it be done?

In a special facility, Powers said, the inmate would sit in a chair and would be immobilized by some kind of apparatus. Officials would put a target over the inmate’s heart. Families would be invited to watch, as is the case with all executions in the state.

One marksman on the firing squad would shoot a blank so no one would really know who fired the fatal shots. He said other states have had more volunteers help to carry these out than they needed.

In a hearing last week, Sen. Todd Gardenhire’s (R-Chattanooga) curiosity on the matter got a bit dark.

“I’ve read that when somebody tries to commit suicide with a pistol or a shotgun, sometimes they flinch,” Gardenhire said. “They’re pulling the trigger and they just maybe blow half their face off, but they still live.

“I’m only going by what I’ve seen in Western movies. I haven’t ever seen a execution or an execution by a firing squad, you know, you say, ‘Ready, aim, fire!’ What happens if the guy or lady flinches and you don’t kill [them]? Do you reload?”

While professional in explaining the details, Powers has gotten frank about how he feels about inmates being put to death. Rep. G.A. Hardaway (D-Memphis) read depositions to him from other states that said “death by firing squad would not significantly reduce the risk of severe pain.”

“Any type of death … it’s going to be painful,” Powers said. “The death that they promoted and carried out for another subject was painful, too. So I don’t have a whole lot of empathy for people that suffer pain during an execution.”

This is the same response given by the bill’s Senate sponsor. Last week, Sen. London Lamar (D-Memphis) was tearing the bill apart. A facility would have to be built. It was going to cost way more than the $50,000 fiscal note (maybe $1.5 million). The bill was unconstitutional, and every state that has passed it is in a mess of costly legal proceedings. Finally, she said, it is “morally wrong.”

“Why would we want correctional officers to sit there and point guns at an individual as a form of killing?” Lamar asked. “It’s almost legalized first-degree murder. That is not cool and we do not need to be a state that sits there and allows people to use individuals as if they’re dummies in a gun range.”

She finally asked Sen. Frank Niceley (R-Strawberry Plains), the bill’s sponsor, “You don’t think this is pretty cruel?”

“You don’t know what that person did to that little girl or that little boy or that old man,” Nicely said. “No, it’s not cruel. It’s not cruel at all.”

The bill needed to clear one more hurdle in the Senate as of press time. The House bill cleared the committee system but will not be considered until after a state budget is passed.

“We don’t need to be doing this in secrecy.”

Rep. Justin Lafferty (R-Knoxville) wants the public to know the companies that make the state’s lethal injection drugs and he’s clear about why.

“If the lethal injection protocol had been more transparent, perhaps [Smith’s] last-hour stay would not have happened and the victims’ family would not have had to have gone through all of that and then, again, have to wait for their day of justice to come.”

The transparency issue tripped up some lawmakers considering the bill last week. Won’t that scare off the drug companies who don’t want to be associated with executions? Aren’t these drugs already hard to get? Won’t this open up the companies to get hounded by activists?

Neither journalists nor the FBI could find any documented case of threats to companies by death penalty abolitionists, Deborah Fisher, executive director of the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government, told the committee. The Tennessean found the state’s drug-maker was El Paso-based SureCare Specialty Pharmacy, and Fisher said they’ve not reported any harassment so far. She also said neither Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, nor Utah have such a secrecy “loophole.”

As for getting the drugs for executions, Lafferty relied on cold economics, saying, “If there’s a profit to be had, somebody will find a way to get the product to market.” As for the ultimate reason for his bill, he came to the point.

“If Tennessee wants to continue this as a method of execution, the secrecy around the process should probably come to an end.”

TBI

TBI  TBI

TBI