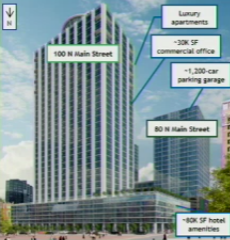

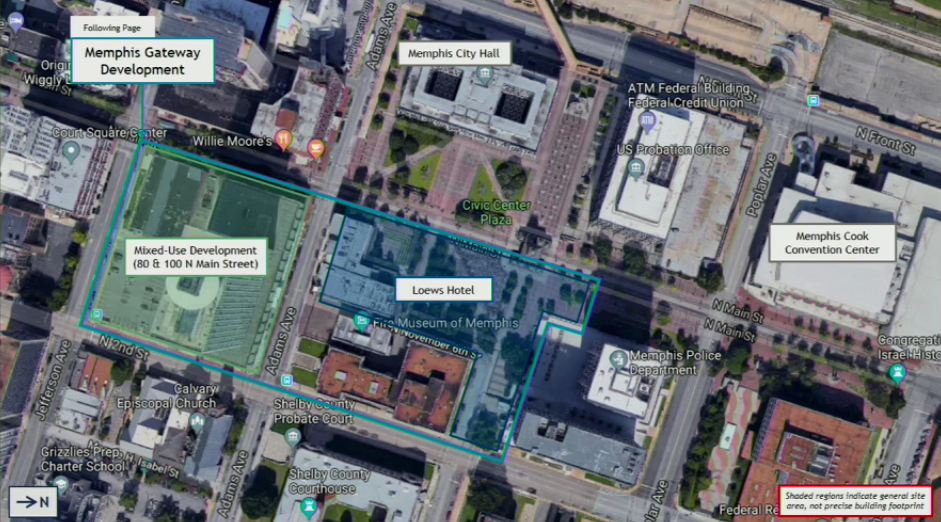

A critical decision looms on a years-in-the-making plan that could transform one of the largest pieces of public property in Memphis.

The stakes could not be higher for the city’s plan to turn the largely fallow Memphis Fairgrounds into a youth sports tourist magnet. It’s the end of the road. There’s no appeal. There’s no review-and-update process. The city either gets the money and builds a “world class facility,” or it doesn’t get the money and then, well, who knows? The plan lives or it dies.

The city wants to create a Tourism Development Zone (TDZ) around the Fairgrounds. An increment of state sales taxes would be collected in the zone to pay for the project. The problem is that legislation approved in the Tennessee General Assembly this year deadlined consideration for any and all outstanding TDZs at December 31, 2018. And the only one left to be considered is for Memphis’ youth sports idea.

The high stakes were enough to cause city officials to hone the plan, shrinking the project in scope, size, and price tag. Meanwhile, local grassroots advocates for the Fairgrounds and the Mid-South Coliseum have continued to beat the drum of local access to the property and for re-activiation of the building. Through it all, developers have stayed mostly on the sidelines, waiting to see if the plan gets an up or down vote before they move in.

If the city’s plan is approved by the state, the Fairgrounds could get a brand-new, multi-million-dollar, state-of-the-art indoor sports building, retail shops, a hotel, play areas, and more. It’s a play to attract out-of-towners and their sports-playing children (and the tax dollars that come with them) to the city.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

How We Got Here

The most recent moves to reanimate the Memphis Fairgrounds began in 2005, 13 years ago. Back then, the city was “eager to revitalize and re-imagine,” the Fairgrounds, as reporter Ben Popper wrote in the Flyer at the time.

“It is really the nexus between East Memphis and what is going on Downtown,” Robert Lipscomb, then-director of the city’s Housing and Community Development (HCD) division, said at the time. “I think it’s under-utilized and potentially has much greater value. Our job is maximizing that asset.”

That year, Lipscomb formed a special Fairgrounds Redevelopment Committee to envision the Fairgrounds’ future. The architectural firm Looney Ricks Kiss drew up six proposals for the site.

The group picked an option with “large green space, small-scale retail, and 40-plus acres for sports and recreation.” The plan did not include Libertyland, the Mid-South Coliseum, or the Mid-South Fair. The committee’s selection decision came on the same day leaders decided to close Libertyland, citing several years of financial losses.

Retail, green space, sports, and recreation. Sound familiar?

But then-Shelby County Mayor A C Wharton told the Memphis Business Journal‘s Chris Sheffield at the time he wasn’t in a hurry to get anything done “given the nostalgia and fond memories and public importance of the property. There’s nothing wrong with going through a laborious process,” Wharton said in 2006.

Laborious, indeed. Two years later, John Branston, writing for the Flyer, described the scene at the Fairgrounds this way:

“The stadium and the Children’s Museum [of Memphis] still draw crowds, but the rest of the property is demolished, abandoned, or underused. Libertyland amusement park, part of its roller coaster still standing, is closed. So is the Mid-South Coliseum, home to concerts and basketball games … before giving way to The Pyramid and then FedExForum.

“Tim McCarver Stadium was demolished a few years ago,” Branston wrote in 2008, “long after it was replaced by AutoZone Park. The annual Mid-South Fair is moving to Tunica, Mississippi, next year. Fairview Junior High School is blighted and has about 300 students. The main feature of the Fairgrounds on most days is several acres of asphalt parking lots.”

Those comments came in Branston’s story about a new group heading up a new push to, finally, finally, finally get something done at the Fairgrounds. It included a heavy-hitting bunch of names: Henry Turley, CEO of Henry Turley Co.; Bob Loeb, president of Loeb Properties; Archie Willis III, president of Community Capital; Mark Yates, now-Chief Visionary Officer of the Black Business Association of Memphis; Jason Wexler, president of business operations at Memphis Grizzlies; Elliot Perry, retired pro basketball player; and Arthur Gilliam Jr., president of Gilliam Communications.

Called “Fair Ground,” the idea was to make the Fairgrounds a common area for all Memphians to meet, play, and mingle. At its core, Fair Ground would have transformed the sleepy area “into a combination of sports complex, renovated stadium, park, and retail center.” Sound familiar? A big difference, though, was that Fair Ground also promised a “network of new public schools” good enough to rival private schools.

In 2007, the city applied for its TDZ with the state and the Salvation Army Kroc Center bought a parcel of land to build upon. But by 2009, Lipscomb was referring to the Fair Ground deal with Turley and his folks in the past tense. He said they couldn’t come to an agreement. He pivoted quickly to a Plan B, in which Lipscomb tapped former Memphis City Council member Tom Marshall to design a plan that centered on — wait for it — sports, recreation, and retail.

That $125 million plan was ultimately panned, though the city did add that formal TDZ request to its quiver. A 2009 Flyer headline read, “The Fairgrounds: Big, Complicated, and Leaderless.”

Come 2013, another plan — this one with a $233 million price tag — centered on (surely you guessed it by now) sports and retail. By 2014, Lipscomb was reported selling the plan to the Shelby County Commissioners in a Flyer story by Jackson Baker. Some commissioners worried the TDZ would “cannibalize” future sales tax from Cooper-Young and Overton Square and that the scheme would siphon funds (maybe $1 million to $2 million every year) from Shelby County Schools.

“But it hardly seemed to matter as Lipscomb, at his super-salesman best, seemingly had the members of a commission largely revamped by the election of 2014 treating Lipscomb’s propositions like ‘candy in the palm,'” Baker wrote.

Lipscomb, who Baker described as “the city’s veteran Svengali of urban planning,” said the buildings that would rise on the Fairgrounds would be “world class,” helping to raise “a great new city right before our very eyes.”

Commissioners loved it. Van Turner congratulated Lipscomb. Terry Roland called it a “world-class deal,” and only Steve Basar and Walter Bailey seemed cautious.

That was November, but by December, commissioners shelved a vote on Lipscomb’s plan, hoping to bring a compromise plan of their own.

In January 2015, Lipscomb told city council members he’d bring his plans to state officials in February. But public concerns crept into Lipscomb’s plans, fears that Fairgrounds neighbors and local stakeholders were being left out the conversation. Lipscomb vowed to get more people involved. That was February.

To get there, the Urban Land Institute, a third-party group of of city planning professionals, had a look at the plan. Their $184-million recommendation included sports and retail, natch, but also more improvements to Tiger Lane, a park with a lake, a surf park, a “Coliseum stage,” and more. That was in June.

In August, Lipscomb said he’d take the new plan to state officials in October. But when allegations surfaced that Lipscomb had raped a young man, his grand plan for the Fairgrounds was stalled, to say the least. Memphis Mayor Wharton fired Lipscomb immediately.

The Plan’s “New” New Era

Jim Strickland was elected Memphis mayor in October 2015. He hired Paul Young, former director of legislative affairs for Shelby County government, as director of HCD. Plans for the Fairgrounds weren’t really discussed much for two years.

In 2017, rather than starting from scratch, Young dusted off the recommendations from the Urban Land Institute panel (with youth sports and retail as the centerpiece, of course). But Young and the Strickland administration did something different this go-around. They began the conversation of the Fairgrounds’ future in public forums and actually used some options they got to shape the final plan. This was August 2017, and Young hoped to present his plan to state officials by the end of that year.

In November, Young unveiled the new $160-million Fairgrounds plan. It included an $80 million youth sports complex, retail and hotel space, a 500-space parking garage, $20 million worth of upgrades to the Liberty Bowl, upgrades to nearby Tobey Park, renovation of the Pipkin and Creative Arts buildings, basketball courts, a track, a soccer and football field, renovations to nearby Melrose High School, and new infrastructure to spur investment at Lamar and Airways.

But Young (some say on the advice of the state officials who’d vote on the plan) decided to have another look. Earlier this month, he brought a scaled-back, “workable” proposal to Memphis City Council members, who approved it. Almost everything (save for the $20 million improvements for the Liberty Bowl) was shaved. Two youth sports buildings became one. The parking garage was halved, basically. Off-site projects were cut out of the plan.

Courtesy of Allen & Hoshall

Courtesy of Allen & Hoshall

Why?

“As we really dove into the specifics and saw that TDZ revenues were much lower than we expected them to be, it was incumbent on us to take some time and really, really hone down the plan and try to figure out what things do we have to do to make this site activated,” Young said in an interview last week.

So, now — with more than a decade of plans, dreams, opinions, and varying degrees of political will on the project — Young and his team are slated to take their plan to Nashville later this year. If the State Building Commission doesn’t give the city the money, the Fairgrounds will stay largely the same as it is today, Young said.

Money Ball

At the very core of the new plan — and almost every plan proposed so far — is youth sports. That might not be what you think it is. It’s not your kid’s T-ball team sponsored by a local insurance agent. Youth sports is a big, sophisticated business. The teams the city wants to attract are called travel teams or competitive teams. The kids who play are elite (or at least seen that way). Not every kid makes the team. Those who do practice at private facilities, wear custom uniforms, carry custom equipment bags, get elite coaching, travel around the country to tournaments, and pay mightily for the privilege of doing so. Many parents see these teams as a path to help their child get a college scholarship and then, perhaps, to play in the bigs. In short, these parents often are monied and motivated.

How much money? According to WinterGreen Research, an independent organization that tracks the youth sports market, the U.S. market is worth $15.5 billion. There’s more.

“This is a nascent market, there is no end to growth in sight,” WinterGreen reported in September 2017. “Markets are expected to reach $41.2 billion by 2023.”

Young says the Memphis sports market is worth $120 million, without an indoor youth sports facility. The Rocky Top Sports World in Gatlinburg created $35.4 million in economic impact for that city last year, according to Young’s report. A Fort Myers, Florida, venue yielded $47.7 million. Another in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, grossed a whopping $186 million.

Critics of the city’s Fairgrounds plan have said that leaders want to build an elite facility for rich kids and their rich parents.

“It’s not for them,” Young responds. “It’s for our economy.”

Young adds that the facility would be available to locals anytime it isn’t being used for youth sports tournaments, which usually run from Thursday through Sunday.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Reviving the Roundhouse

In 2015, some Memphis folks got together and decided they wanted the Mid-South Coliseum saved and re-opened. After years of community meetings, government meetings, tours of the building, business research, creating a business plan, media interviews, three Roundhouse Revival events, and a top-to-bottom examination of the massive building, they are still at it. They say the future of the Coliseum has never looked brighter.

“There is a wider wind in our civic sails, and we’re racking up civic win after civic win after civic win with Crosstown Concourse, the Chisca Hotel, the Levitt Shell, the Tennessee Brewery, Broad Avenue, and Clayborn Temple,” says Marvin Stockwell, co-founder of the Coliseum Coalition and a second group, the Friends of the Fairgrounds. “This seems a whole lot more possible than it did when we first started, and way more possible than it did 10 years ago.”

That enthusiasm is shared by Coliseum Coalition president Roy Barnes and Charles “Chooch” Pickard, a coalition member and preservation architect, even as the city’s new plan (and just about every plan so far) aims only to “preserve” the Coliseum. To them, preservation is at least a step away from razing the building, as Lipscomb wanted to do.

Two Saturdays ago, July 21st, hundreds of people sweated together outside the Coliseum, with 90 degrees of Memphis summer sun blasting from above and radiating back off the parking lot. Barbecue smoke scented the air, vendors sold vintage T-shirts, and a brass band covered the Meters’ classic “Cissy Strut” inside a wrestling ring.

It was the third spin of the Coliseum Coaltion’s Roundhouse Revival event, which featured music, wrestling, food, and a few public service announcements. “The Coliseum is in great shape,” read a flyer posted on a column. The group has used the events to garther input from community members and garner support for their cause.

“I just saw these photographs over here that show me that the building is in great shape,” said Tennessee gubernatorial candidate Craig Fitzhugh, at the event. “To me, now it’s a perfect-sized venue. It won’t compete. There’s not any competition for it. They could put a lot of different things in here — from music to wresting to whatever — roller derby. For the Grizzlies, this would be a great place to put their … developmental league team.”

Fitzhugh hit upon the No. 1 problem for re-opening the Coliseum, according to the Coliseum Coalition — the Grizzlies non-compete clause. With the clause, Grizzlies officials have a measure of control over the local entertainment market and local venues. The team is on the hook for any operating losses at the FedExForum (not the local government) and might perceive a revived Mid-South Coliseum as competition.

That was city council members’ central argument against Elvis Presley Enterprises’ proposed $20-million arena in Whitehaven. And it’s been a central argument against re-opening the Coliseum. Barnes thinks it’s bogus.

“There’s nothing in it … that gives the Grizzlies the ability to say, ‘Sorry you can’t re-open the Coliseum,'” Barnes says. “It doesn’t give them the ability to say, ‘You can’t have events there.'”

Only certain events are blocked by the clause, Barnes says. Stockwell says that the perception that the clause blocks any new, large-ish venue from opening is “completely false.” But there is little political will to alienate the Grizzlies, a major city brand and a major corporate citizen, Barnes says.

The Coliseum, Pickard says, should be right-sized to about 4,900 fixed seats with about 1,000-2,000 on the floor. That would make it the perfect venue for up-and-coming artists and established artists who are playing their way back down the musical food chain from arena shows.

“We’ve gone to the Grizzlies and said, ‘We think there’s a market for that,’ and they said, ‘We don’t think there is, but if there is, we can accommodate those shows,'” Pickard says. “We’re the venue for that.”

While there seems to be little movement ahead for changing perceptions on the non-compete or the clause itself, the Coliseum Coalition is moving ahead, working with city officials to allow them to clean up the inside of the building and, perhaps, hold a new event inside. They hope if the TDZ is approved and successful, funds could be found down the road to save the Coliseum.

Plan B = Status Quo

So, what if the TDZ is not approved?

Some sources the Flyer talked to said a “no” vote could be used to further punish Memphis for its removal of Confederate statues this year. Others said moderate Republicans have convinced their right-wing colleagues the deal would be an economic development win for the state. Part of that deal, too, sources said, was the satisfyingly loud outcry from Memphis Democrats over the state lawmakers’ removal of $250,000 from the city’s bicentennial celebration, which was some tasty red meat for Republicans.

In that case, political tea leaves may point to approval of a TDZ for the project. But if it’s defeated, nothing happens.

“I think the Plan B is the status quo,” Young says. “It’s what we have today. When the mayor came in, he commented that the Fairgrounds, while we’d love to see it maximized, it’s not something that had to be done at that point in time.

“I think that opinion would still ring true. It is underutilized, but it’s not necessarily having a negative impact on the community as it sits today.”

Townhouse Management Company/Lowes Hotel & Co

Townhouse Management Company/Lowes Hotel & Co  Townhouse Management Company/Lowes Hotel & Co

Townhouse Management Company/Lowes Hotel & Co  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Courtesy of Allen & Hoshall

Courtesy of Allen & Hoshall  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon