Number One

You can’t do any better. For six weeks straight, Mark Ronson’s “Uptown Funk” has dominated the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Unless you’ve been living under a rock in East Tennessee, you know it was recorded in Memphis at the legendary Royal Studios, home to Al Green and his guiding force, producer Willie Mitchell. Mitchell passed away in 2010, but his grandson Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell has assumed the mantle with great success. The current number-one single is only part of what’s going on under the new generation. We talked to Boo and to Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon, who came to Memphis as the lyricist for much of Ronson’s album Uptown Special.

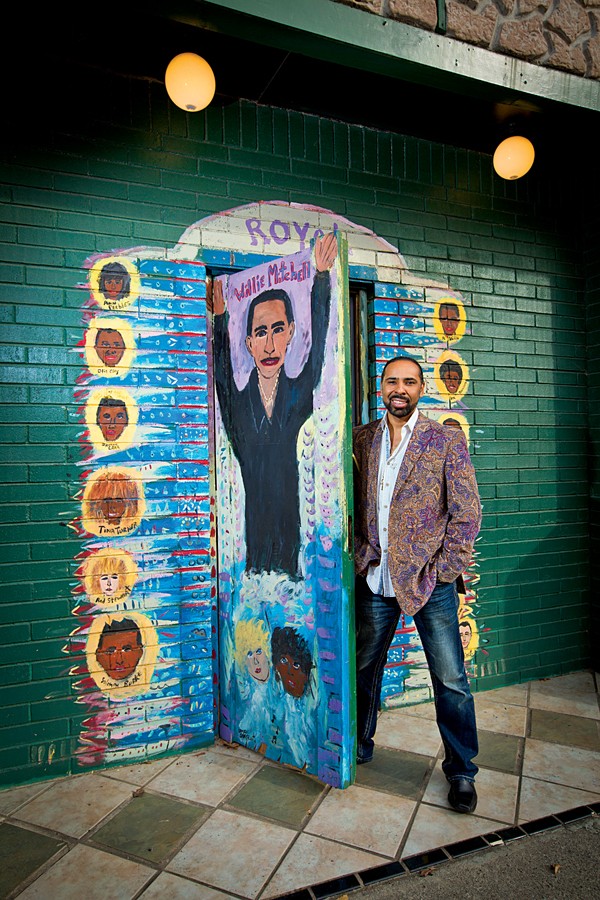

Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell, grandson of Willie Mitchell, at Royal Studios

We Got the Funk

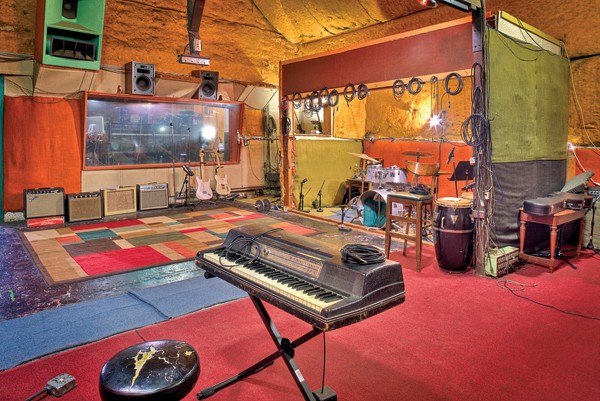

“Initially, I don’t think Royal was in the plan for them to record, until they came in and saw it and felt the vibe and the energy of the place,” Boo Mitchell says of Royal Studios. “It’s something about the studio that inspires people. It’s got a vibe to it. A lot of studios don’t have a vibe. More modern places, you kind of have to take your inspiration with you. This one still has all of the charm from the 1960s. We haven’t touched anything since 1969. We’ve updated the bathrooms and the green room. But when you walk into Royal, it has this magic quality to it. That’s what got ’em.”

In a city where Sun Studios was rebuilt, Stax was torn down and replaced, and American Sound was destroyed, Royal remains an untouched working example of the Memphis Sound. It’s impressive on every level.

inside Royal, working example of the Memphis Sound

“When they got here, they were kind of blown away by the studio,” Mitchell says of the producer’s visit last winter. “Mark, when he walked into the control room, said, ‘Aw, man, you have the same MCI recording console that I have. I remember that I bought it because your dad had it. That’s why I got it in the first place.'”

Three weeks later, Ronson returned with a band of musical assassins including producer Jeff Bhasker, Kevin Parker of Tame Impala, drummer Steve Jordan, bassist Willie Weeks, and some guy named Bruno Mars. March 1st was Willie Mitchell’s birthday, and the group gathered for a photo in front of the studio. The resulting album,

Uptown Special, is currently at Number 11 on the Billboard Top 200 Albums chart and peaked at Number 5. Ronson is famous for melding classic sounds and modern sensibilities. Mitchell delivered the tools to do just that.

Mark Ronson walked into the control room and said, “Aw, man, you have the same MCI recording console that I have.”

“Everything we used was vintage,” Mitchell says. “Eric Martin at Martin Music gave us a whole lot. When Carlos Alomar [David Bowie’s guitarist] came, we had all kind of stuff. Marshall amps. And then the Drum Shop, we went and raided them for the first session. We sent Homer Steinweiss [Amy Winehouse, Dap Kings] to the Drum Shop. [laughs] He came back with like five kits. But Steve Jordan would use this hybrid kit: the Royal Studios hi-hat from ‘Love & Happiness’ and some weird low tom from the Drum Shop. We had all kinds of madness going on.”

Engineer work on Uptown Special is not all Mitchell has going on. He is co-producer with Cody Dickinson on Take Me to the River, a documentary that pairs musicians from different generations in a celebration of soul music’s enduring power. The film, which pairs artists such as William Bell with Snoop Dog and Mavis Staples with the North Mississippi Allstars, won Best Feature Film at London’s Raindance Film Festival last September. Mitchell had just returned from a show at the Apollo to support the music-education efforts of the project.

Boo Mitchell took on a lot of responsibility when his grandfather died, and he credits the film with helping him get to where he is now.

“Cody Dickinson was one of the first cats to go, ‘Hey, man, you produce the stuff. It’s all you,'” Mitchell says. “Okay. Cool. Then all of the sudden, I’m recording Snoop Dog and Terrence Howard and William Bell and Otis Clay and Bobby Rush. Frayser Boy. Then it seems like the doors opened from there.”

Keep It Rolling

Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell was born in 1971. Willie Mitchell is his matrilineal grandfather who adopted him to keep the family name. Boo remembers the Al Green era and has been soaking up lessons from Pops since he was a child.

“Just remembering about how Pops used to talk to the musicians and dealt with the band and the artist,” Mitchell says. “I spent summers down here, from the time I was 8 or 9. I just wanted to be here. Pops would tell you be quiet and don’t talk. I remember he told me one time, ‘When you go in the studio, never ask how long it’s going to take.’ We were doing a percussion overdub, and this guy was taking all of this stuff out of the bag, a glockenspiel. He says, ‘How long is this going to take?’ Pops goes, ‘It’s already done. You can pack your stuff up.’ He said, ‘Go see the lady at the front.’ He said, ‘Boo, you might be in the studio one day. You might be here three days. You never know.’ I never asked that question.”

Since Pops’ death in 2010, Boo has kept things moving in his own right: Robert Plant, Paul Rodgers, Boz Scaggs, and Wu-Tang Clan all worked in the studio with Boo at the console.

“It feels good that I was smart enough to keep the legacy going,” Mitchell says. “It’s not something that I ever thought about doing. I wasn’t one of the type of people who’s like, I’m going to do this and do that. I was just the rover. I was just doing things out of necessity. That’s ultimately how I started being a full-time engineer again in 2004.”

Boo remembers the moment he started engineering as a serious career.

“Pops was sitting up there, kind of upset because the current engineer had gone on vacation without telling anybody,” Mitchell says. “[There was] this big Al Green project where the record company wanted this song remixed. It was a deadline. I just looked at him and said, ‘Well, hell, I know how to engineer, and you’ve got the best ears in town. Why don’t you and me go back there and do it?’ He looks up and goes, ‘Damn, that’s a good idea. Let’s do it.'”

That kicked off a special phase of their relationship and set the stage for Boo’s current successes.

“I would pick Pops up from the house and take him to work and take him home every night,” Mitchell says. “That started around 2000, 2001. I would play records. We started listening to Willie Mitchell instrumentals. He would tell me, ‘That’s Fred Ford.’ The stuff was so old, he’d forget. We’d listen, and he would say, ‘That’s Fred Ford playing the solo on ‘Bad Eye.’ I had no idea. So it was cool listening to these old records with him. He started remembering. I’d ask him how he mic’ed the drums. He said, ‘Everybody wants to know how I mic the drums. This is how I did it.’ That was cool.”

Mitchell is the current president of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences Memphis Chapter and represents Royal and Memphis all over the country. He has become the consummate professional and a leading ambassador of the Memphis Sound.

“That’s the path of my life,” he says. “Doing things because it’s the right thing to do has blessed me. It’s opened doors for me, and good things have followed.”

Q&A

Michael Chabon, The Accidental Lyricist

Michael Chabon

Mark Ronson asked Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon (Mysteries of Pittsburgh, Wonder Boys, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay), who is a crate-digging music nut and Big Star fanatic, to contribute lyrics for Uptown Special. While Chabon did not write the lyrics to “Uptown Funk,” he contributed to most of the other album tracks and made the trip to Memphis for the family-style recording sessions. I asked Chabon about the project and his experience in Memphis.

Memphis Flyer: The story of Ronson and Bhasker renting a car and driving around the South looking for talent has been well-reported. Sometimes we roll our eyes when people “drive through the South” in search of something. But this time it worked. What’s your take on that?

Michael Chabon: We don’t a have a whole lot of mythology in America. A lot of the mythology that we do have — I almost want to say we used to have — was kind of artificial. It was artificially devised creations starting around the turn of the last century, where there was kind of this effort both conscious and unconscious, with all of the immigrants pouring into the country from all over the world, to kind of shape a narrative of what America was and what American history was. That brought us all of these things like George Washington throwing the dollar across the Rappahannock River and the stories of the founding fathers. That kind of iconography of American history was like our civic religion. That was kind of an American mythology that was dreamed up by the equivalent of marketing people essentially. There wasn’t a whole lot of basis in fact.

The real, organically grown mythology was pretty scarce. But the birth of the blues in the Mississippi Delta and the migration of that music up the river and the way that it metamorphosized into jazz, R&B, and gospel — all of that stuff and the cross-cultural fertilization with the European, everything that’s part of that story are mythological elements. There are clearly bogus elements, like Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil or whatever, but the basic story is true. You can drive around. I didn’t get to drive down to Clarksdale, but I would want to do that too. You would just be hoping that you would be touching or be touched by something that’s true: something old and true.

So much of everything that’s around us now is cooked up and synthesized. Whether you’re white or black or whatever … everyone wants authenticity. Authenticity has the highest premium on it of almost any kind of experience that we can have as human beings. Whether that’s even possible or not, it’s certainly hard to find in a contemporary context that we live in. So you’re always kind of looking for places.

What about that building?

It’s an expression of a single human soul and a single human consciousness. That’s how it felt to me anyway, to go in there. It reminded me of outsider artists. There’s a guy in France called the Facteur Cheval. In the 19th century, he was walking down the road one day, and he picked up a rock. There was something about this rock that got stuck in his brain. He ended up building this entire palace complex in the backyard of his house in rural France out of rocks. He spent his whole life working on it. It’s an incredibly surreal environment.

That studio itself and the way Boo explained it to me: There was something that he would hear that wasn’t quite right about the drums, and he would get whatever there was around, like a blanket or a piece of foam and just stick it in exactly the spot. Over the years, all of that stuff accumulated, in this way that you feel like you’re inside of a work of art, not just a recording studio. It’s an installation or an environment that’s reflecting the way one particular brain operated.

The Mitchells are some fun people.

Boo is so lovely. His spirit is so wonderful. You just like being around him. It is such a family operation there. You felt so taken care of. They want to know about you and your family. One of Boo’s aunts cooked up Sunday dinner for us and brought over all of this incredible food, this amazing red velvet cake. Boo’s kids and nephews. But not just that, the whole neighborhood: There’s that lobby area, and every time I’d walk through there would be different people sitting around in the chairs. Teenie [Hodges] was there a lot. But just guys from the neighborhood … they’d be talking and laughing. Sometimes I would just come in and hide around the corner and eavesdrop. I’ve never heard people laughing so hard. Just cracking each other up so much.

They know they are doing something wonderful. There’s a magic they have: this trust, this thing that’s been entrusted to them, this studio that Willie made. They know that it’s special, and they want to share that. They want people to see how wonderful it is. They know that people have choices; there are other studios. You get a sense that they are grateful that they have this place.

So much of what Memphis had is gone or has been replaced.

That’s they way of the world. It’s always been that way. There’s no more Big Star supermarket. All of that’s gone. It’s magical. Long may it reign.

Robert Allen Parker

Robert Allen Parker  Photo: Glen Brown

Photo: Glen Brown