Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Water whooshes through two black pipes — both as big around a small pizza and long enough to hide their ends — with the gentle sound of a dishwasher humming out of sight.

The pipes snake nearly across the entire campus of the Allen Fossil Plant. For nearly 60 years, nearly all of Memphis’ electricity flowed from the massive plant close to Presidents Island.

That plant burned coal to make that electricity. That coal was reduced to mainly to ash when it was all burned up. That ash — containing toxins like arsenic and lead — was slurried with water and flowed into great ponds sitting just west and just east of the Allen plant.

Those ponds sit right on the bank of McKellar Lake, a broad inlet from the Mississippi River that cradles the south side of Presidents Island and fronts Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park and T.O. Fuller State Park.

Google Maps

Google Maps

An aerial view of the Allen Fossil Plant.

In 2017, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) found high levels of arsenic and other toxins in ground water close to the ponds. Arsenic levels were more than 300 times higher than federal drinking water standards.

The discovery kicked off a years-long, sometimes-contentious series of events that TVA officials hope will end in 10 years. That’s how long they say it will take to finally remove the ash now sitting on nearly 120 acres.

Environmental and drinking-water advocates here hope that move will finally remove the threat the has poses to the Memphis Sand Aquifer, the source of the city’s pristine drinking water.

The process to remove the ash is already underway. On Wednesday, those two black pipes — both as big around as a small pizza — whooshed treated water from those ponds straight into the Mississippi.

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

TVA president and CEO Jeffrey Lyash spoke to reporters here Wednesday.

“There’s a deferred cost associated with the nearly 60 years benefit we all derived from places like the Allen Plant,” Jeffrey Lyash, president and CEO of TVA, said to reporters here Wednesday. “That deferred cost is coal combustion residuals [ash] and the decommissioning and dismantling of the plant and the restoration of the site so that it can be repurposed for economic development.”

Two ash storage ponds now hold ash buried at the Allen plant from as far back as 1959, when it was built and brought online by Memphis Light, Gas & Water.

The west ash pond was the site’s first. It was retired in 1978 and closed by the TVA in 2016. The ash in that ponds — some from 1959 — remains. Though, the broad pond is now covered in grass and a few trees. It looks inviting enough, as one TVA official put it, for a family reunion.

The east ash pond replaced the original west ash pond. The east pond was built in 1967, expanded in 1978, and is now 70 acres, according to the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project. Water in the pond looked dark, standing about 50 yards from it. The area around it looks swampy, grown over by some tough, reedy weed — not inviting at all.

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Reporters gather before pumps and filters on the bank of the Allen plant’s east ash pond.

Crews began sucking the water from the east pond about two weeks ago, according to Angela Austin, TVA’s construction manager at Allen site. Lyash, the CEO, called Austin the “boots on the ground” for the project to remove the coal ash and decommission and dismantle the old plant.

In those two weeks, nearly 3 million gallons of free water — the water on top of the ash — has been removed from the pond. The water is filtered to remove any particles in it and treated to adjust its pH to clear federal standards that allows TVA to dump the water in the river. Austin said she hopes to have all of that water removed in the next two or three months. When it’s gone, nearly 17 million gallons will be filtered, treated, snaked through those black pipes, and flowed into the Mississippi.

Once that water is gone, crews will begin removing water that’s still in the ash. Once that water is gone, the ash will be stabilized enough to be removed.

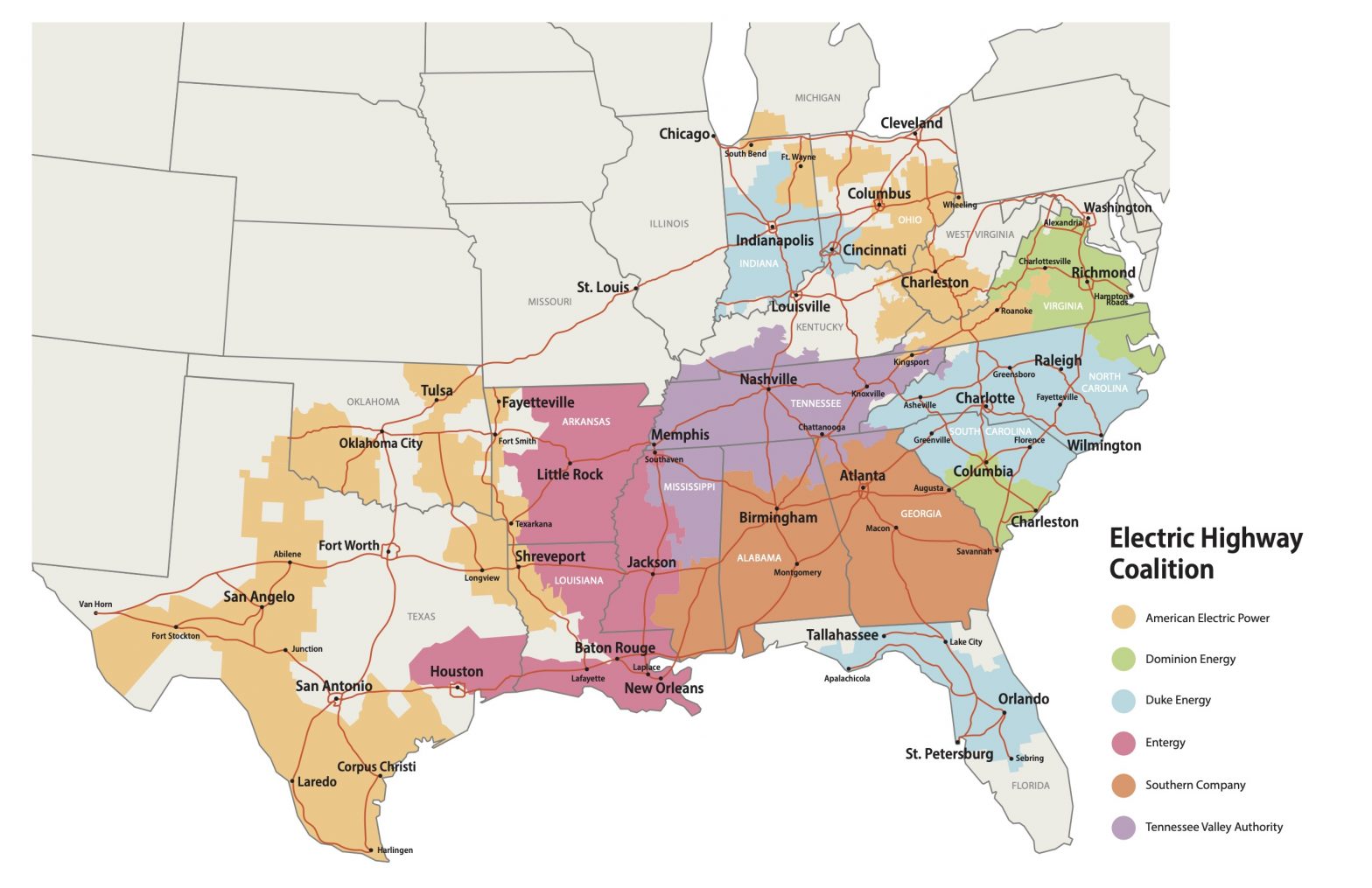

Coal ash ponds near TVA’s Allen Fossil power plant

TVA wants to remove it, Lyash said, all of it — from the east and west ash ponds. But part of that decision lies with federal environmental officials and with Memphians. A process is now underway to decide exactly how the TVA will deal with the ash.

As a part of that, TVA held a public hearing on the matter here Wednesday. Lyash said Wednesday TVA is also going to create a citizens advisory group to watch and review the process on an ongoing basis.

The process underway now will determine many of the next steps TVA will take to remove the ash. Can the agency remove it? If so, how? If so, how can they transport it? Truck? Rail? If they can transport it, where can they take it? If they can take it some place, what kind of container can they store it in?

Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center

An aerial shot shows the massive east ash pond at the Allen Fossil Plant.

One interesting question is whether or not TVA will be able to use the ash, instead of just storing it some place. The American Coal Ash Association (ACAA) said in 2012 that about half of coal ash that is reused is made into concrete, grout, or gypsum wallboard.

But the biggest question for Memphians is how TVA plans will protect the environment and, more specifically, the drinking water here.

Contaminants from the coal ash ponds leeched into groundwater here. It made it 40 feet into the ground into a shallower alluvial aquifer, not into the drinking-water source, TVA said. Around the time of the discovery, TVA said it wanted to drill five wells into the Memphis Sand (the drinking water source) to pump water from it to cool it’s brand new Allen Combined Cycle Plant, the one that replaced the fossil plant.

TVA

TVA

TVA’s new natural-gas-fueled Combined Cycle Plant.

However, some worried that running the wells would pull toxins from the east ash pond into the Memphis Sand aquifer. TVA launched an investigation run by the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Memphis. The groups found that the Memphis Sand was hydraulically linked to that contaminated, alluvial aquifer above it. By this time, though, TVA had decided not to use the wells.

“All the evidence says not only isn’t there any drinking-water contamination or environmental contamination beyond what we’ve characterized, but there really isn’t any migration that would suggest it would be an issue in the future,” said Lyash.

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Two of 57 wells monitor the ground water around an ash pond at the Allen plant.

TVA is watching the situation closely. It has now expanded its of monitoring wells around the east ash pond to 57.

But Memphis will have a second opinion. In November, to the U of M’s Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER) wont a $5 million grant to study the aquifer over the next five years.

A U of M news release at the time said MLGW “has grown increasingly concerned over water quality impacts to our sole source of drinking water, the Memphis aquifer. Above the Memphis Aquifer is a protective clay layer which shields our drinking water from pollution, but gaps, or ‘breaches’ in the clay have been discovered.”

Lyash said TVA will return the Allen site to a “best-of-industry standard” using the “best-in-industry practices in science.”

“We’re going to protect the environment,” Lyash said. “We have the interests of the citizens of Shelby County in Memphis right at the heart of that. So, you shouldn’t be concerned that TV is going to do anything other than the right thing here at our Allen.”

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

TVA’s Angela Austin speaks to reporters at the Allen plant.

For Austin, TVA’s mission at Allen is personal. She’s the “boots-on-the-ground” Allen construction manager. Austin said she has been a Memphian for 24 years and lives now in Hickory Hill.

“It’s very important that we get it right, because I’m the one who drinks this water every day, Austin said. “It has to be successful. This is where my family has been born and raised.”

TVA/Facebook

TVA/Facebook

TVA

TVA  Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center  TVA

TVA  TVA

TVA  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Google Maps

Google Maps  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center  TVA

TVA  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Toby Sells

Toby Sells