John Fahey’s 1968 guitar ballad “Voice of the Turtle” is a classic piece of Vietnam-era musical Americana. The song’s train-like rhythms draw out a melody that is as mournful as an empty boxcar but as defiantly optimistic as the all-American promise of something greater down the line. “Voice of the Turtle” is a kind of frontier hymn colored by the psychedelic urge to “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

This past Saturday night, TOPS Gallery opened an exhibition called “Voice of the Turtle” in honor of the late Fahey. The show features a small, abstract tempera work by the guitarist who took up painting in the years before his death in 2001. Fahey’s painting is shown at TOPS alongside work by eight Memphis artists, many with a similar interdisciplinary bent. The show includes sculpture and drawing by Fahey’s friend and 1960s Memphis scene-maker John McIntire, alongside drawings by William Eggleston, Guy Church, and Jonathan Payne, sculpture by Terri Phillips and Jim Buchman, collage by Kenneth Lawrence Beaudoin, and painting by Peter Bowman.

Fahey’s small painting at TOPS is nothing to write home about, at least in light of his talent as a musician. Painting was a secondary art form for Fahey, but that isn’t a bad thing. Plenty of artists, including Bob Dylan, David Lynch, and Eggleston, have exploratory painting practices that often meet with undue critical disdain. TOPS’ “Voice of the Turtle” is an exhibition that celebrates these practices, and references a time when the interdisciplinary (art as a multi-hued journey of personal discovery, rather than as a specialized niche practice) was more celebrated than it is today.

A marble “game” sculpture by McIntire occupies the center of the gallery. To clarify: It is a sculpture made from white marble, but it is also a game of marbles. Viewers are invited to drop a marble into one of the sculpture’s many holes connected to a network of tunnels, and assumably, see where the marble emerges. At Saturday’s opening, no one had any marbles (perhaps having misplaced them in the ’60s? ba dum ching…), but not much was lost. McIntire’s sculpture is still beautiful and playful — the sort of thing you’d expect a favorite uncle to have stashed in his attic.

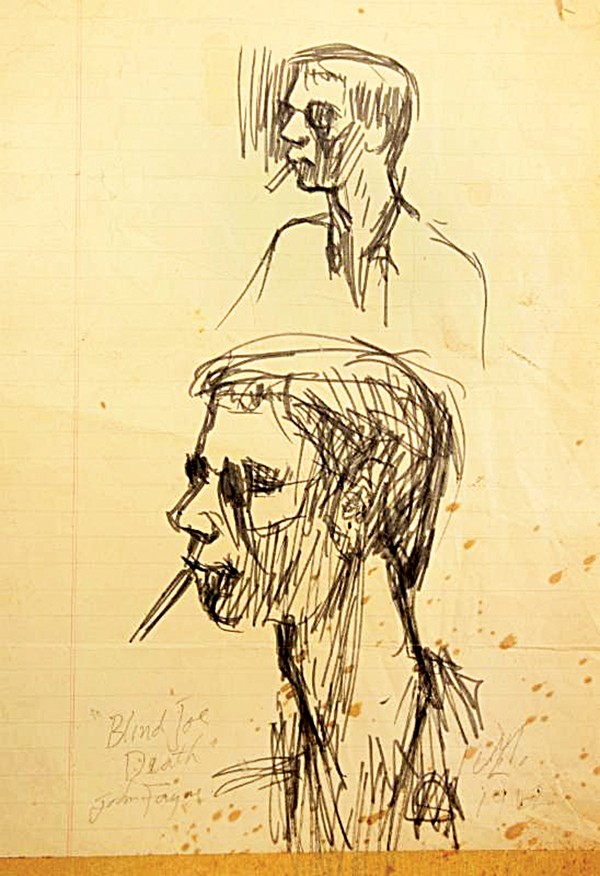

John McIntire’s portrait of John Fahey

McIntire also contributed a small drawing on yellow legal paper of Fahey, sitting in profile, wearing sunglasses. A cigarette hangs out of Fahey’s mouth. The drawing feels like a dashed note, a quick record of a lost conversation. Between this drawing, McIntire’s sculpture, and Fahey’s painting, there is a kind of friendly history — a warm context that makes room for the other featured artists’ work.

Eggleston’s squiggly, colorful drawings are each about five inches tall. There is not much to say about them except that they are really fun, and that every artist should probably make a squiggly drawing once in their lives. Beaudoin’s cut-and-paste collages are assembled from old magazines. They are at once personal and alienated by the material’s faded gloss. Buchman contributed two roughly hewn abstract ceramic works with an understated drama.

The works that pack the most punch are four expertly stippled drawings by self-taught artist Church, whose genre scenes seem drawn from an otherworldly forest. The characters that inhabit this realm are likewise magical; their exaggerated proportions seeming all too natural in Church’s constructions. “Voice of the Turtle” is worth going to see if only for Church’s work.

Another high point in the exhibition is a small drawing by Payne. His elaborate, obsessive mark-making, navigated through hundreds of undulating lines, is quietly done without seeming restrained or restricted. Payne is also the youngest artist in the exhibition, and his presence in “Voice of the Turtle” shows a kind of artistic heritage — a generational relationship between artists that is as open-ended and bravely optimistic as Fahey’s eponymous song.