Fair warning: there’s an undeniable bias in my reportage here, being a frequent band mate and collaborator with the subject of the interview below, native Memphian Greg Cartwright. And yet a certain historical imperative compels me to document the details of this songwriter’s process when his work is deemed so notable by critics and fans alike. That became eminently clear this spring, when a song Cartwright co-wrote with the Black Keys, “Wild Child,” topped Billboard’s adult alternative airplay chart. It was a level of success that’s long eluded an artist who’s typically had more critical acclaim than financial windfall. Yet tomorrow, when the Black Keys appear at the Radians Amphitheater at Memphis Botanic Gardens for Mempho Fest, Cartwright will be able to hear the song echoing through the air from his back yard. Will he raise a toast to the Memphis night?

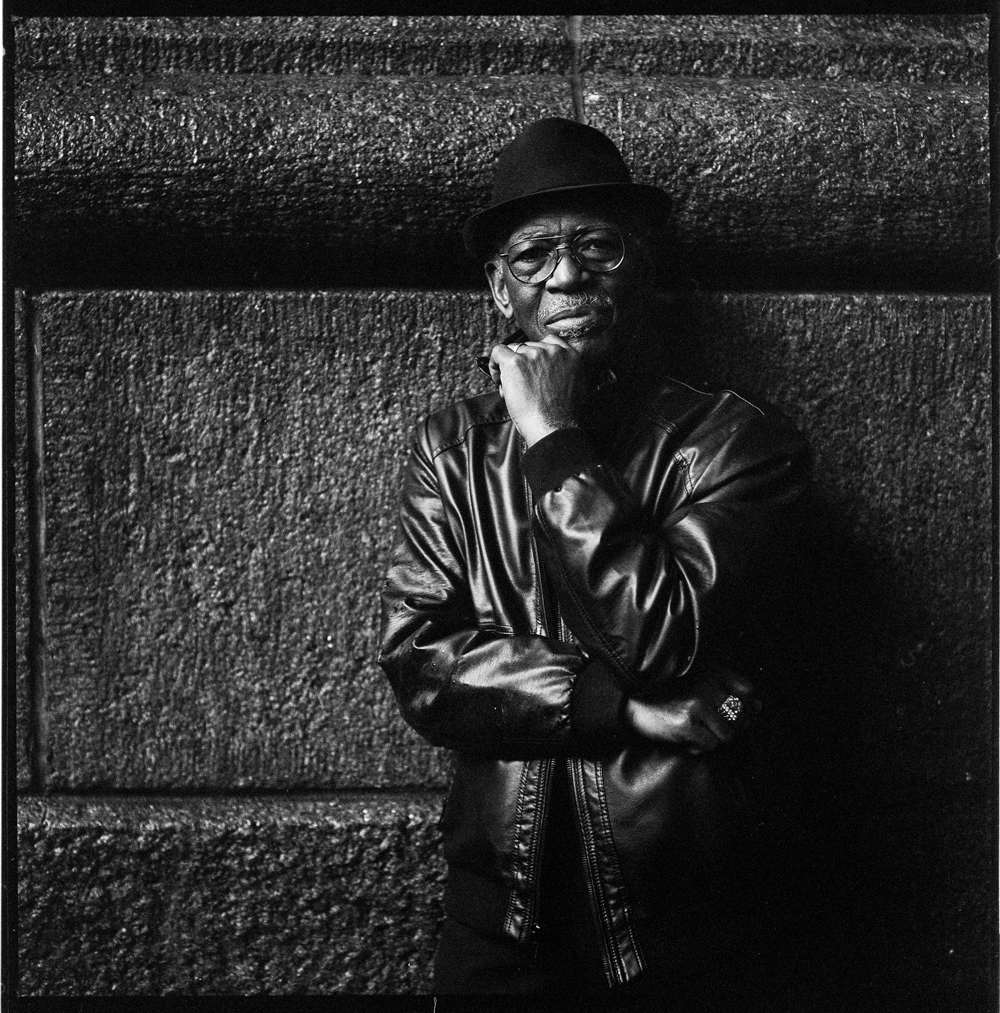

Moreover, this evening, Thursday, September 29th, Cartwright will join Don Bryant and Alicja Trout in the season opener of Mark Edgar Stuart’s Memphis Songwriters Series at the Halloran Centre, with all three artists performing examples of their craft without a band, in the round. At such a moment, how could I resist calling up my old pal Greg to ask him his thoughts on the songwriter’s craft, in all its intricacies and rewards?

Memphis Flyer: You’ll be appearing with a national treasure, soul singer Don Bryant, on Thursday. How do you relate to his work?

Greg Cartwright: Don’s got an amazing voice and range, and boy that guy can sell a song. It’s amazing! And I love that he and Scott Bomar have this cool relationship, where Scott is Don’s producer and bandleader, and I think that’s such a cool older guy/younger guy relationship. And it’s win/win both ways. Scott’s got great skills, too. And he’s going to be at the event, I think, playing guitar while Don sings his stuff.

Also, I’m a huge Lowman Pauling and “5” Royales fan, so for me, it’s cool to work with somebody who wrote a song for them. It’s as close as I’m ever gonna get to doing anything with somebody who was there when all that magical era of gospel and R&B was happening. And Don’s an amazing songwriter. I love all his songs, from the 50’s on, including the more recent stuff that Scott’s produced. And the Willie Mitchell stuff — all great. I know he’s going to really bring it. I’m a little bit intimidated, to be honest. I don’t know if I can sell a song quite as well as he can.

There’s a certain spirit in that older school of songwriting that you have really zeroed in on and emulated.

Yeah, I really have. A lot of Don’s generation is what inspired me, in a lot of ways, to write in the way that I write. So I take a lot more inspiration from that era of country and rhythm and blues as a songwriter. I’ve always tried, when I have an opportunity to perform with or alongside artists from that generation, because I know there’s something I can learn in person that I can’t glean from a record.

You can kind of see how they embody what they do.

Yeah. Listening to records is great. You can get a lot from that, like you can get a lot from reading a book. But to be able to have a conversation with Hemingway would be a lot different. I can talk to him and understand more where the person is coming from. I always find it interesting to meet performers from that era, because it’s a little more insight into what makes the magic happen.

That era of songwriting has influenced you going back at least as far as the Compulsive Gamblers, and even through your Oblivians work.

You know, Jack [Yarber/Oblivian] and I had already done rock and roll, folk, country, all kinds of R&B and all kinds of other stuff with the Gamblers. So when Eric [Friedl] joined us and we did the Oblivians, it was a pretty late-blooming punk band. We were already adults. It was kind of a fake punk band, is what it was. The idea was, “What is punk music? It’s discontent.” So there were a lot of songs about what you don’t want to do [laughs]. And we took a lot of inspiration from the Ramones. That was Joey’s thing: I don’t wanna do this, I don’t wanna go there, “I’m Against It.” Him telling you what he’s not going to do. And that was an inspiration for the Oblivians. A template, if you will.

You’ve mentioned before that you Oblivians thought of your band as both fun and funny. There was a sense of humor to it.

Yeah, there totally was. It was an opportunity to laugh at life. There are some things in life where you can either laugh or cry. And there’s some very dark material in the Oblivians’ catalog. We took a lot of inspiration from the Fugs, which is a very tongue in cheek critique of society, as well as the Last Poets, also with a heavy critique of society, particularly the racist society in the United States. And you might laugh, and then find yourself going, “God, I shouldn’t laugh at that. That’s horrible!” But it is part of looking at what’s going on around you and trying to find some way to think about it that’s not just sad. But yeah, there’s a lot of dark stuff in the Oblivians. And I’m glad I had a platform to do that stuff when I was younger, because I don’t think I have it in me to laugh at a lot of that stuff at this point in my life.

You’ve talked about how with the last Reigning Sound studio album, you were trying to write in a more positive way.

Yeah, that was a big goal for me; because the pandemic, for a lot of people and a lot of songwriters, was a reset button, where it’s one thing to gripe in songs, or complain, but when you’re faced with some kind of new reality where you don’t even get to be around people, well, you stop complaining and you want to find something to be appreciative about. And that’s a better way of putting it. I was looking to appreciate. There are many things out there that are obstacles, always, but if you’re curious about what is happening around you, and you’re appreciative of the good things that come your way…

For a lot of my life, I thought that the gift I had was that I was very good at emoting whatever pain I was experiencing, in a way that other people seemed to relate to. There are a lot of songwriters like that. They really know how to put that into words, and emote it in a way that elicits a response from other people, where they totally empathize. So a lot of times, I would just be in this kind of trance onstage, sort of crying in public, in a way, and people responded to that. And I can’t say I grew out of it. It wasn’t a natural thing. I would have stayed that way if I hadn’t done a lot of work. But on the back side of that work, I wondered if I could also be just as good at emoting appreciation.

A sense of curiosity is important to that kind of openness, isn’t it?

It really is.

I’ve talked to Don Bryant about this, and also William Bell. Certain writers have this curiosity and this empathy, listening to and absorbing others’ stories. William Bell described sitting in cafes, just people-watching and getting song ideas.

That’s very true a lot of times; it’s so important to be curious, listening to people’s stories, because that’s how you find new subject matter. If you were confined to your personal autobiography, that’s pretty limited. I remember that someone once asked Jack [Oblivian], “Where do you get ideas for your songs?” He was like, “Small talk in bars.” Local gossip! If you keep your ears open, there’s plenty out there to write about. There’s plenty of new ways to frame an age old story, if you’re curious enough to see all the options, all the twists and turns.

You’ve known and worked with Alicja Trout for decades now, haven’t you?

A long time! Yeah, so when Lorette Velvette left the Alluring Strange, Randy Reinke took her place. And then I took Randy’s place, and played with them for a couple years. Then I started the Oblivians and started to get busy with that, and Alicja Trout was learning guitar, and it was my job to teach her the Alluring Strange songs, so she could take my place. And that’s how we got to know each other: teaching her songs for Misty White’s band. So there you go, Misty White is the Kevin Bacon of Memphis! [laughs]

Alicja was just learning guitar, and it’s amazing that she’s come so far. It wasn’t that much later, maybe five years or so, that she was doing her own stuff and playing with Jay [Reatard]. But even before she played with Jay, she had a band called Girls on Fire, and that was her and Claudine, who played guitar with Tav [Falco]. They had a band together. And boy, when I saw them for the first time, I called Larry Hardy at In The Red the next day and said, “I found a band I want to record, send me some money!” But before I could make it happen, they broke up. [laughs].

And even at that time, I thought, “Wow, she has really come a long way.” And it really amazed me. She had surpassed me as a guitar player, as far as what she could do as a lead guitarist. Because I’m very limited. For me, I’m always accompanying myself so I can perform a song. I’m not a great lead player. I enjoy the challenge, but I would never say I’m very good at it. But there are just some people that really take to something. They’re really passionate about it, and just want to do it, so I guess she must have wanted it. It didn’t take her very long to become a very good guitar player.

You and Alicja both have one foot in the punk world, the heavier rock world…

Aggression.

Yeah! But you both also step back and write these very delicate songs. Like Alicja’s beautiful “Howlin'” on the album of the same name; it’s mostly just her vocals and quiet electric guitar.

I like a bigger palette, and I think she does, too. As for me, I’m so in love with songwriting. It’s been such a helpful tool for me in my life, in so many ways, to process things, that the bigger palette I have, the better I can express myself. And I’m not very concerned with commercial success. So that gives me even less limitations. I think a lot of artists become very limited stylistically because they’re trying to define themselves as a certain kind of performer, or a certain kind of artist. And there’s no shame in that, but you have to have one eye on the marketplace to do that.

How did your collaboration with the Black Keys come about?

I met them a long time ago, probably about 15 years ago. They were traveling with The Hentchmen from Detroit. So when the Hentchmen played Asheville, they told me Dan Auerbach was a huge fan and wanted to meet me. So Esther and I went to the show and afterwards we had an impromptu jam session, with myself, the Black Keys, and the Hentchmen, and we had a great time and got to be pretty friendly. And I hesitate to say this, but he basically said to me how inspiring he found my work. And that’s a massive compliment. Whether it’s the Hives or the Black Keys or whoever — people who’ve actually had success — for them to say to me, “Wow, you’re a huge inspiration to me, a lot of my art comes from emulating some of the things I hear in your music.”

But it’s an even bigger compliment when someone gets to a successful point in their career, and they say “Hey, would you like to come help me work on these productions and songs?” Dan thought enough of my songwriting that he not only wanted it in the Black Keys, but wanted me to help him with other artists he was working with. I really appreciated that. It helped me in so many ways. It gave me a new income stream, just to have a song credit on a Black Keys record is no small thing, especially if it’s a hit. And “Wild Child” was a hit. The synch license requests are still coming in daily.

But also, I think it opened me up to the idea of collaboration in a way that I had not allowed myself before. So around the beginning of the pandemic, I said I tried to focus more on appreciation, and that was a huge moment of growth. But then doing all these co-writing sessions with Dan also represented a lot of growth for me.

Prior to that, being in so many rock bands … When you’re in a band together, you spend too much time together, and eventually some things end acrimoniously. It was definitely that way for me. Prior to the Reigning Sound, the Oblivians spent too much time together and started to get on each other’s nerves. Then Jack and I went back to the Gamblers for a while, and we thought we could do that, but we quickly found out that we still, underneath it all, needed to get away from each other.

So when I started the Reigning Sound, my idea was that I would start a band where I would be the benevolent dictator, and everybody would have to do what I said. And I would be good to everybody, I would pay everybody fairly and be equal, but it would just be my songs and the covers I picked. I had never been the boss before, but at that point in my life, I needed that level of total control. Because I didn’t trust people. I had been burnt, I had had relationships that crumbled. And this kind of happens in romantic relationships, too, where you get to the point where you think, “I just need to be in control. I can’t relinquish any control because I might get hurt”. If you can’t be vulnerable, being in control is kind of the obvious option. And luckily I met you and Greg [Roberson] and Jeremy [Scott], and you guys were cool with that. You’re all great songwriters, so to find a bunch of talented people who understand music and get where you’re coming from, who aren’t going to be angry that you don’t want to consider their songs, that’s tricky. And for that same reason, it can’t last forever.

And I came to a point where, when I wrote this last record [A Little More Time with Reigning Sound], I thought, this is a much more positive side of my songwriting, but it’s also the last great burst, for a while, of me needing to have a band where it’s just me and my vision all the time. Now what I really want is to learn how to be vulnerable with other people, and to open up to other people’s ideas. Right now, I really want to do that. You have to tread lightly, and pick people that you trust. You have to pick people that feel safe, and then you can be vulnerable, and then you can be playful.

Did your collaboration with Dan Auerbach begin during the pandemic?

It did. His engineer Alan called and said, “Dan would really like you to come and write. Are you available these days?” So I went, and I had no idea what we would be doing, or who I’d be writing with or for. I assumed it was Dan; I thought maybe it was a solo record or something.

So I got there, and Dan said, this guy Marcus King is going to be here in a half hour and we’re going to write. And it kind of scared me! But as soon as Marcus got there, he was so friendly and open and funny that we had a great time. We got right to it and had four songs in a day. And a little while later, Dan called me back to work with another guy he’d signed, Early James. And we ended up doing two writing sessions together.

And after that, Dan said, ‘I’ve got another one.’ I asked him who it would be with, and he said, ‘It’s the Black Keys.’ [laughs]. So I went and we talked about some song ideas. He played me some jams that he and Pat [Carney] had recorded, with some hooks and stuff. So I went home, sat with them for a couple ideas, thought about lyric ideas, song ideas, chord changes that might be beneficial to the riffs that they had. And I went back and we sat around that day and wrote the rest of the songs. And I wasn’t sure what was going to happen at that point, but they just walked into the other room immediately and started recording. It was instantaneous. They recorded them just as we had worked it out together, then Dan put down a vocal, and that was it, we were done.

I’ve never experienced anything like that in my life! Usually you write a song and there’s weeks or months in between that moment of inspiration and when it gets laid down on tape. But Dan loves the idea of catching something when it’s fresh. There’s some kind of magic there that you might lose if you continue to play and record it. And I think that’s what makes the Black Keys work, especially when you listen back to their earliest stuff, that’s kind of raw and live, like the early Oblivians stuff. There’s not a lot of production going on, and not a lot of adjusting it after the fact. It is what it is.

It also speaks to how carefully you crafted it right out of the gate.

Right, you did all your thinking already. And I think Dan’s very much like the early Billy Sherrill and Rick Hall and all those people. They’re his heroes. And back in their heyday, pre-production was everything, because you couldn’t do much once it was on the tape. It was so limited, track-wise. So pre-production was everything. Where are the mics gonna go? Are you gonna play loud or soft? How are you going to sing it? Everything had to be figured out before the tape rolled. And then you got what you got. And I think Dan appreciates that way of thinking. He tracks live to one inch 8-track, the same as the last few records I’ve made. I’m enamored with it as well. I love the idea of planning everything out on the front and then just recording it.

With something like “Wild Child,” some people may not associate it with ‘great songwriting,’ because it’s more primitive. It’s not, say, Leonard Cohen-style lyrics or whatever, but a lot of craftsmanship really goes into riff-oriented songs as well, doesn’t it?

Yeah. The song is two chords. It’s about as simple as a song can be. To me, that requires even more work. How do you build all these dynamics and cliffhangers and hooks and everything if it’s just the same two chords over and over? So it’s almost more challenging to make a really fun ride out of those two and half minutes. And I think that’s how people used to work back in the day. Now artists and musicians have the option of, “Well, you can lay down the basic track and continue to tweak it and add things and take things away, ad nauseam.” That is definitely a way to build a song. But it doesn’t really speak to me. And also, it’s exhausting. Because you’re never really sure when you’re done. If you’re doing all this stuff after you record it, editing and stuff, where do you stop? The way people used to do it, when you stopped was when it was recorded, and then you just mixed it.

It must have been very gratifying to go through that process in a day or two, and have one of those songs become a hit.

Yeah, it’s been a real experience, to say the least. I knew the date it was coming out, and I was really anticipating it, almost voyeuristically, like, “Boy, nobody knows I’m part of this, and I get to just watch it all happen.” But then it came out and all this press came out, and there was my name in every interview, talking about the process and my songwriting. So I felt a little bit vulnerable in a way I wasn’t anticipating, which was a little scary. I thought I was just gonna be a name in a credit on a record label. I didn’t think they’d actually talk about me. But I was also really appreciative of that, once I became comfortable with it. They were trying to tell the world I’m a good songwriter. What a nice thing to do.

I always enjoyed the feeling of sitting in the audience at a Big Ass Truck show, say, watching my songs be performed by others.

I know what you mean. There is that feeling of like, “This will stand!” This will stand on its own. I don’t have to be there animating it. It’s not me, it’s the song. And that is a great, great feeling. You’ve built something that will last, and that other people can inhabit. People will empathize so much with the lyric that they want to deliver it themselves.