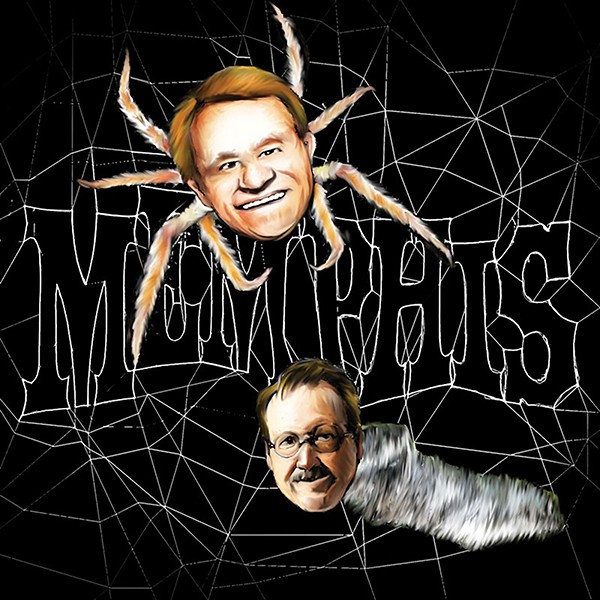

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens

About Bruce VanWyngarden’s editor’s note, “Sammons ‘R Us” …

I read Bruce VanWyngarden’s editorial for the March 12th issue with stunned disbelief. We’re all supposed to be happy not only that this “connected” character, Jack Sammons, has lots of power but also will now “run” a newspaper? Never mind how irrelevant your paper is now. Surely one doesn’t have to go all the way back to the great muckraker days to find journalists who would be troubled by a chief officer of anything running their own paper? And I guess your new position on “pesky laws” that prevent conflict of interest is that they are unnecessary relics of the past? But congratulations on thoroughly brown-nosing your new boss on his way through the door.

John E. Cox

Editor’s note: Mr. Cox, I read your letter in stunned disbelief, as well.

About Bianca Phillips’ cover story, “Getting Schooled” …

Sounds like a lot of territorial bickering between two entities, “This is my school yard and I don’t care if you want to put down green grass for the children to play on; our dirt yard is just fine, so go away.” Our local school system has failed for years in educating our children and it sounds like the schools that have been taken over by the ASD are making a lot of positive gains and turn-arounds. The priority here is educating our children and we should be willing to do whatever it takes to get this done.

Pamela Cates

About Wendi C. Thomas’ column, “The Long Shadow” …

If the family structure is a primary predictor of an individual’s life chances, and if family disintegration is the principal cause of the transmission of poverty and despair in the black community over the past 50 years, then family integration will stabilize the institution and offer children hope.

For once and for all, we must reach out and “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Walking on eggshells out of fear or guilt, being angry at the sins of the past, or throwing money at a problem that only the heart can solve must end.

MempHis1

It’s a puzzle: “middle and upper class parents who hoard opportunity for their kids” are the same people who oppress by riding in bike lanes.

Brunetto Latini

About Jackson Baker’s post, “Flinn: Change of Venue Not the Reason for Leaving Council” …

Personally, I’m glad Shea is leaving. His lack of lunacy and apparent common sense really took away from the overall character of the council. Ditto for that other stick in the mud Jim Strickland. We need more dancing and redacted credit card invoices!

Smitty1961

About Tim Sampson’s Rant …

It was interesting to discover that three of the seven Republicans who did not sign Senator Tom Cotton’s letter to the leaders of Iran were Bob Corker, Lamar Alexander, and Thad Cochran.

For these three men, it would have been in their best political interests to go along with the rest of their Republican colleagues. But they put their country above their own political interests and refused to sign a letter that was so wrong and dangerous in so many ways and one that may guarantee that a deal in the best interests of the U. S. and the entire world is not reached.

These Senators should be praised for showing real leadership and real political courage.

Philip Williams

About Bruce VanWyngarden’s editor’s note, “The Heart and Soul of Memphis” …

I was born and raised in Memphis but now call Nashville home. I live in the middle of one of the hottest neighborhoods in the country’s “It City,” but still miss the soul of Memphis. It’s something that all the new money, popularity, real estate prices, and relocated hipsters will never understand … and certainly can’t replicate.

MT Blake