Mike Davis

Mike Davis

L.D. Beghtol in Memphis, 2001

“You’ve got a devastating point of view and everything you say is true.”

— Stephin Merritt,“The Way You Say Good-Night.”

From 69 Love Songs, performed by L.D. Beghtol

“Sweep everything under the rug for long enough, and you have to move right out of the house.” ― Rachel Ingalls, Mrs. Caliban

This is a bad story. There are worse stories, and sadder ones, usually involving orphans, serial killers, and/or extinction events. But the astonishing L.D. Beghtol is dead and no story beginning with news like that can be any kind of good. More than this, if you knew him, knew of him, or only recognize the sweetly whispering voice of “All My Little Words,” and other superb tracks from The Magnetic Fields magnum opus 69 Love Songs, no amount of accolades or fond accounting can make the bitter batter better. So be forewarned. If happy endings are your kink — if you like stories that make you feel better, affirm life, balm grief, and order the unruly world, if only for an estimated engagement time of 4 minutes — this isn’t the story you’re looking for.

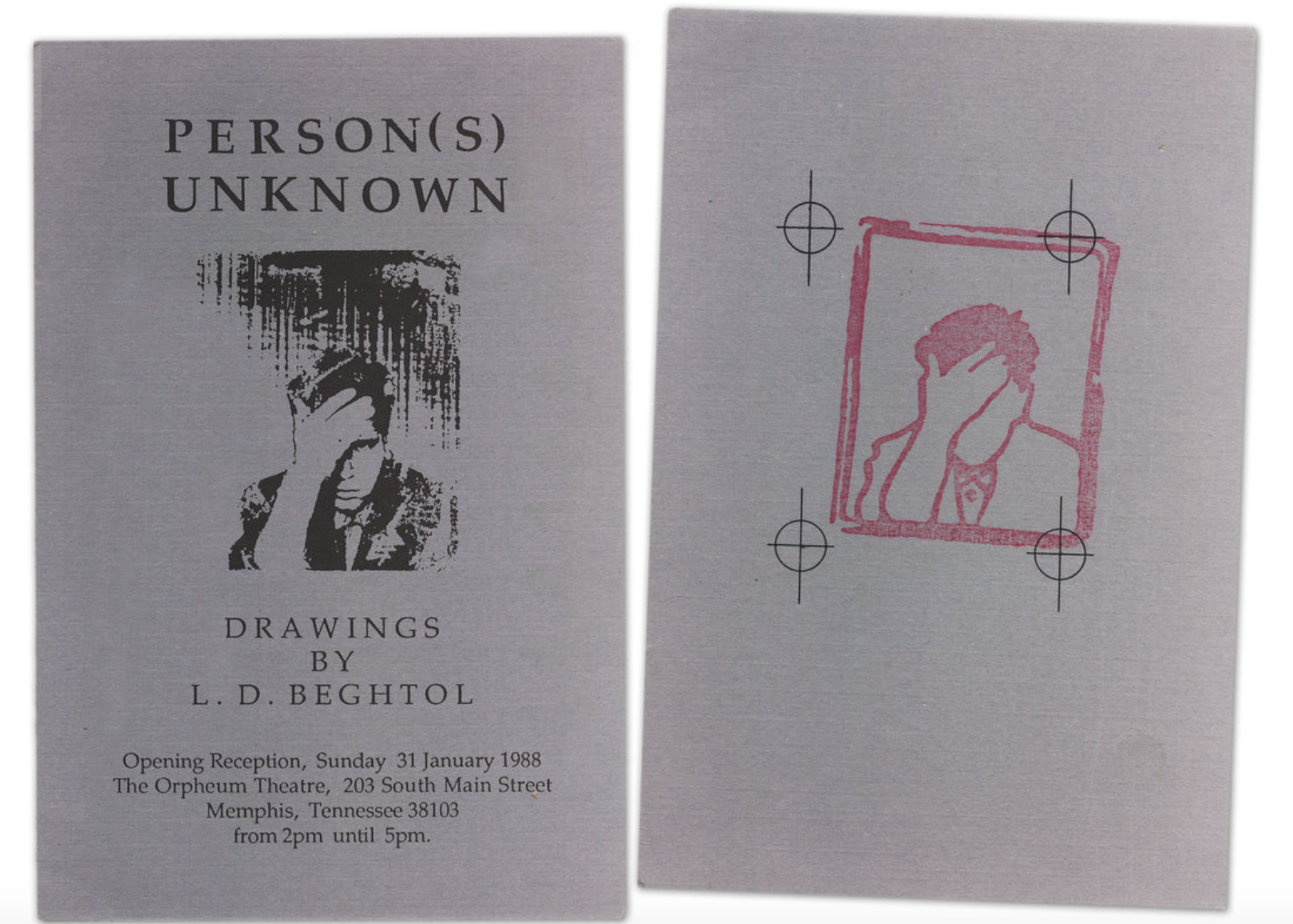

L.D. arrived in Memphis in 1983. If that wasn’t tragic enough, he went by Larry, something people don’t forget half as quickly as you’d hope. Nevertheless, Larry persisted, rapidly distinguishing himself as a notable artist, designer, curator, pot stirrer and mischief maker. During a dozen-year run in the Bluff City he worked with Towery Publishing, organized art happenings, and fastidiously studied the lives and habits of famous murderers, while penning witty, literate art and music columns for periodicals like No: and The Memphis Flyer.  LD Beghtol

LD Beghtol

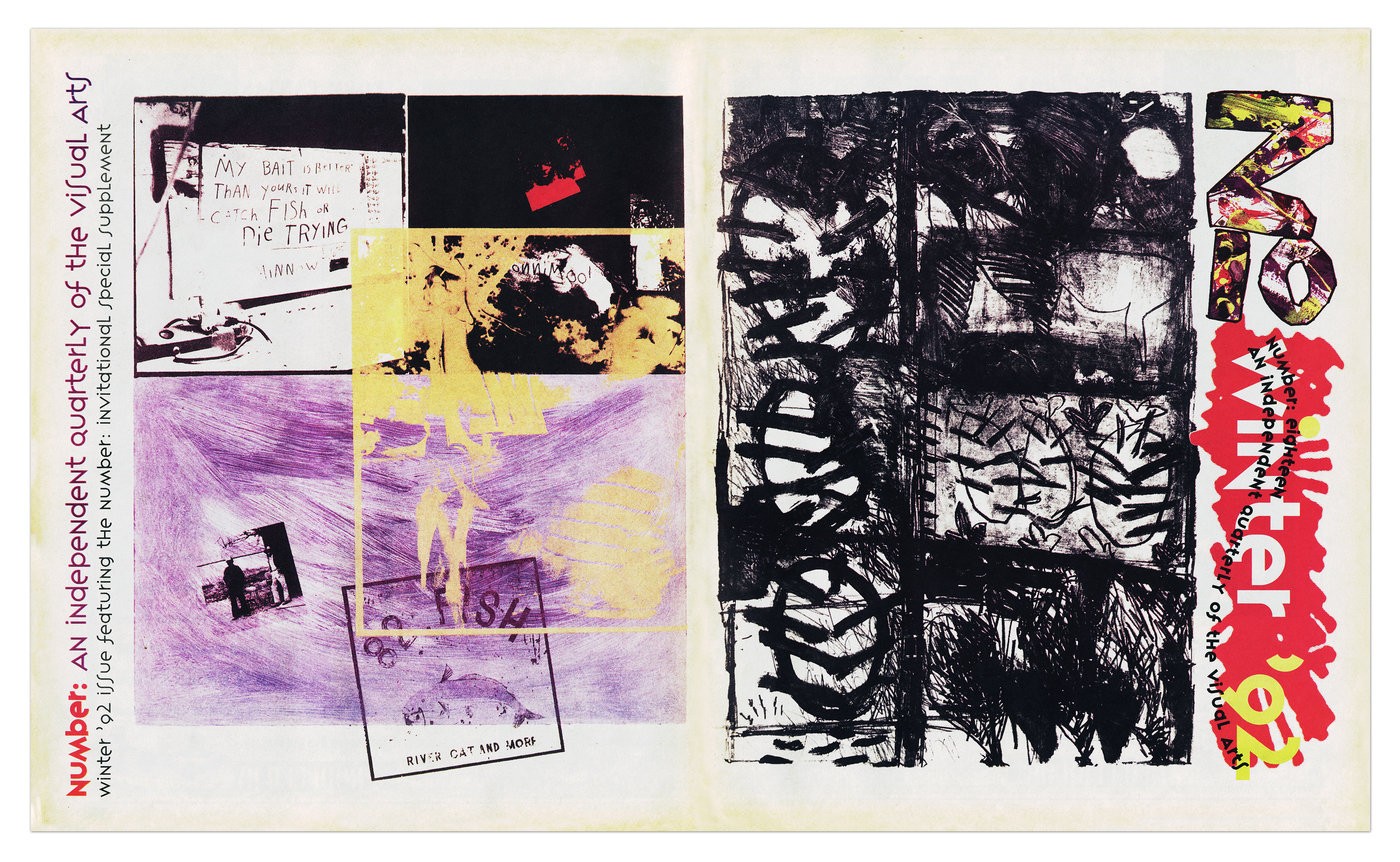

Vintage No:

This industry came to no good end, of course, unless you reasonably stretch definitions of good to include a close proximity to biscuits from Bryant’s, everything from Cozy Corner, and a hidden rooftop pool atop that 19th-Century townhouse on Jefferson where Tallulah Bankhead’s parents were married; the pool that could only be accessed through a secret bookcase panel in an upstairs study and allowed for occasional naked swimming.

LD Beghtol

LD Beghtol

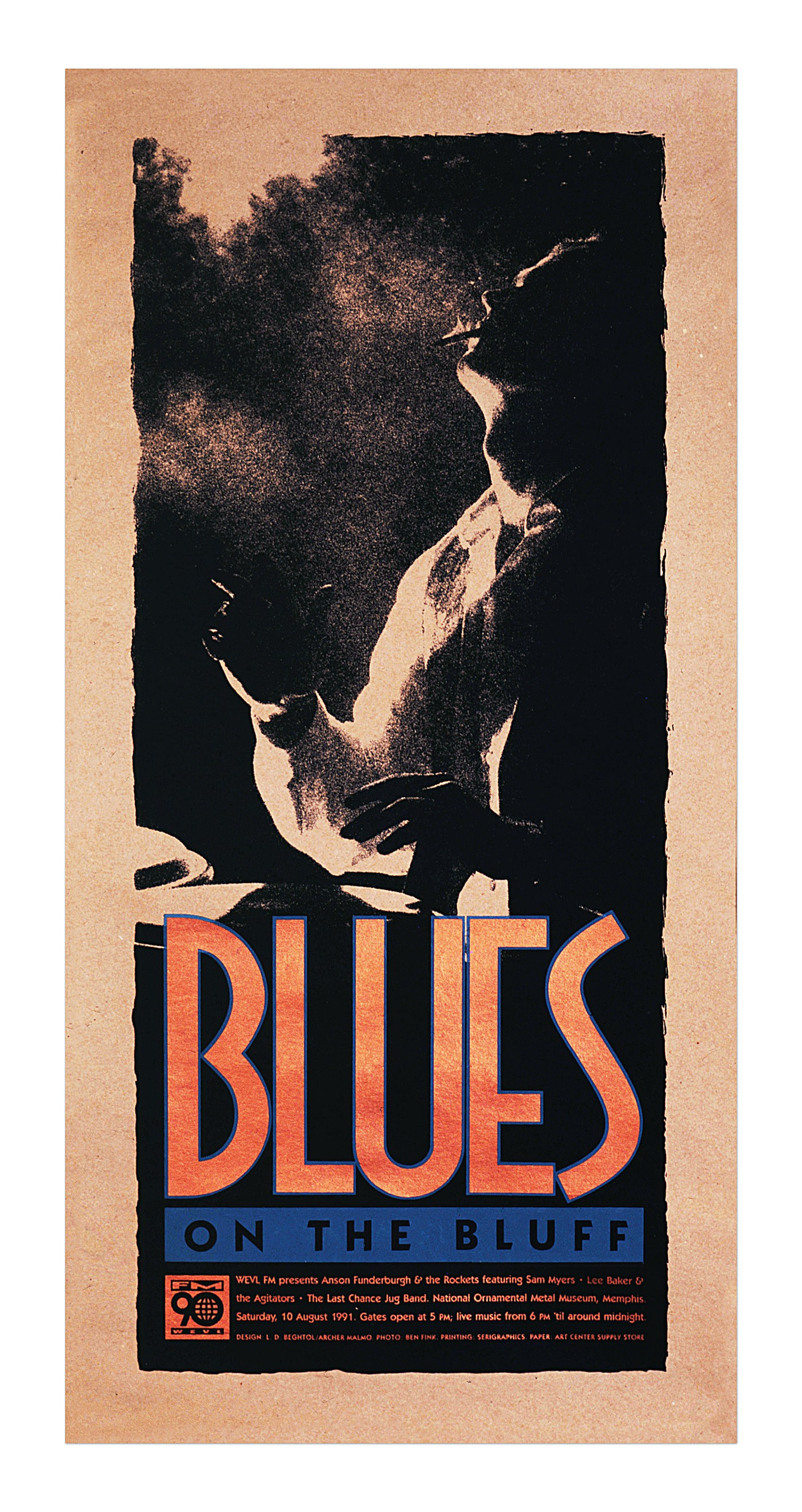

Sometimes things at least felt right, and good, and true, even if hindsight shows nothing could be further from the truth. To reign in this sprawling disaster, here’s a rundown of relevant facts. Before moving to New York with a sum total of $400 in his pocket, dreams of being a famous art director, a beard that amounted to little more than chin stubble, a good friend with a Christopher St. apartment, and no intention whatsoever of ever meeting indie rock guru Stephin Merritt, or recording some of the late 20th Century’s most critically acclaimed songs, L.D. was one of the busiest all purpose designers and art directors in Memphis. Between books, corporate ID and colorful posters for plays, concerts, and cultural events, his lovely and provocative work defined graphic Memphis and was ubiquitous to the Midsouth’s visual landscape.

Not content to work in two dimensions only, L.D. co-founded Nice Boys From Good Families, a multimedia arts collective. Nice Boys kick-started rave culture in Memphis while staging posh art openings and a beloved underground production of Vampire Lesbians of Sodom at Marshall Arts Gallery.

LD Beghtol

LD Beghtol

Blues on the Bluff

I’m leaving a lot out. L.D. was my friend and a vector of fascination. Without him I wouldn’t have met my wife or started a family, or a band, or learned anything about good skin and beard care, or how to cook chicken livers like a champ. I have so many personal stories illustrating L.D.’s wit, unmatched erudition, and complete inability to separate living and making. But all those stories would make you feel things, and, as I heard him scold so many times, “Feelings are wrong, Chris!” They lie to us, and confuse us, and make us think something matters, when it’s simply not true. So none of what I’m telling you so far is L.D.’s true and terrible story. It barely qualifies as an incomplete list of things accomplished by a professional polymath making transgressive, out-and-loud art in the conservative South while fostering fellow artists whenever and however he could.

At the risk of sounding like I’m writing an obituary — which would make L.D. cross — it’s necessary to continue in this vein a moment longer. The media company kind enough to publish our horrible tale deserves a few clicks, and doing so ups the odds of someone finding this article by searching for “Magnetic Fields” and “Singers who aren’t Stephin Merritt.” Speaking of…

In 1997, while living in an apartment above the Stonewall Inn (not the one occupied by Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson), and working as the art director for the Long Island Voice, L.D. became acquainted with Merritt, already an established force with musical projects like Future Bible Heroes, and the Gothic Archies. They shared tastes in literature and drink and a mutual fascination with bizarre old musical instruments. It wasn’t long before L.D., Merritt, Claudia Gonson, Daniel Handler, and various other Magnetic Fields regulars and irregulars were hard at play making 69 Love Songs.  LD Beghtol

LD Beghtol

Cover design, 69 Love Songs

L.D., Merritt, and Dudley Klute (Kid Montanna, Magnetic Fields) also joined forces as The Three Terrors, staging an infamous series of cabaret performances. These are the creative associations and efforts for which L.D. is best known. He’s also known for making gingerbread. And for knowing all the best people, and where to obtain good Vietnamese food wherever you happen to be stranded.

Were it not so clearly against the artist’s famous, if sometimes misunderstood anti-sentimentalism, it might be appropriate to spend some time reconsidering all the bands L.D. helmed, and a body of recorded work that rivals his better known collaborations in terms of pop literacy and most other kinds of literacy, really. To honor his contrariness, however, and his special love for the Carter Family song “Give Me Roses While I Live,” I’ll spend no time ruminating on The Flare Acoustic Arts League or L.D.’s ability to craft meticulous lyrics about grim subject matter, and spin it all into an audio adventure as funny it is bleak. We’ll skip right over the superb Moth Wranglers project and Tragic Realism, an eschatological romp by LD & the New Criticism where high honky tonk and vaudeville collide in a gorgeously imagined effort sometimes worthy of The Fugs at their scatalogical best.

By this point, astute readers are probably asking themselves, “If none of this was really LD’s story, what is?” Critical readers additionally wonder, “And do we care?” Answers, in order, are, “I’m coming around to all that,” and “Not if you’re fortunate.” A number of friends commenting online have, to my mind, mistaken LD’s anti-sentimentalism for being unsentimental. It’s given them pause, and weird feelings about sharing their own memories in a sentimental way. I too know how he felt about cheap sentimentality, which he sang about beautifully, but preferred to observe from afar. But we’re also talking about a grown man who decorated his personal space like it might belong to a little boy who died a hundred years ago. For this reason alone, we should probably expand our views of sentimental life, and briefly consider a childhood that, to hear LD tell it, was often unhappy and sometimes spectacularly cruel.  Courtesy of Galen Fott

Courtesy of Galen Fott

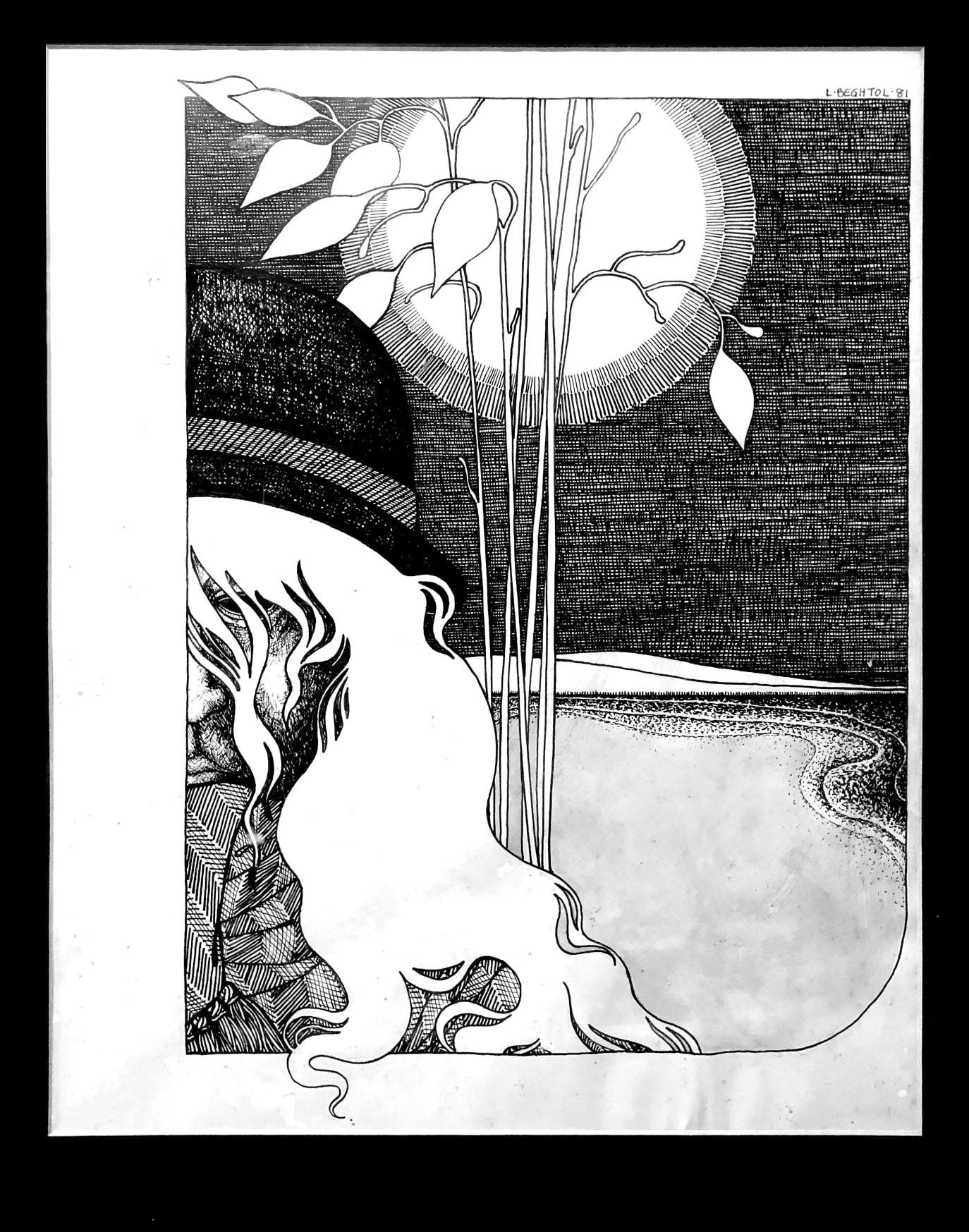

‘Godot,’ a Clarksville High School-era illustration by LD Beghtol.

Old Clarksville’s a city on the Cumberland River in Middle Tennessee, carved into steep hills near the Kentucky border. L.D. might want readers to know there’s now a bronze statue of Clarksville’s most famous actor, Frank Sutton, located on Franklin Street, across from The Roxy Theatre, a place where Sutton — best known for playing Jim Nabors’ arch-nemesis, Sgt. Carter on the hit TV show Gomer Pyle U.S.M.C. — never actually performed. For context, he might also want you to know that bronze statues of Confederate soldiers remain, and that the city borders the Ft. Campbell U.S. military base where L.D., being part of a military family, was born fabulous.

There’s much to consider about L.D.’s time in Clarksville, where he discovered the art of Aubrey Beardsley, the mystery of perfect cornbread, punk rock, musical theater, and the joys of madrigal singing. This is also the place where our story takes its first turn for the worse. How else could it turn? One time, when L.D.’s family was out for a drive, the front half of a deer with enormous antlers came crashing through the passenger side window of the car. The terrified animal started thrashing around while the car skidded and swerved, and the deer bucked and kicked to disentangle itself. “My sister lived,” he’d say, dryly. I mention this event only to further suggest that, as troubling memories go, this was one. And to assuage any ideas that L.D.’s Gothic leanings were anything but earned.  LD Beghtol

LD Beghtol

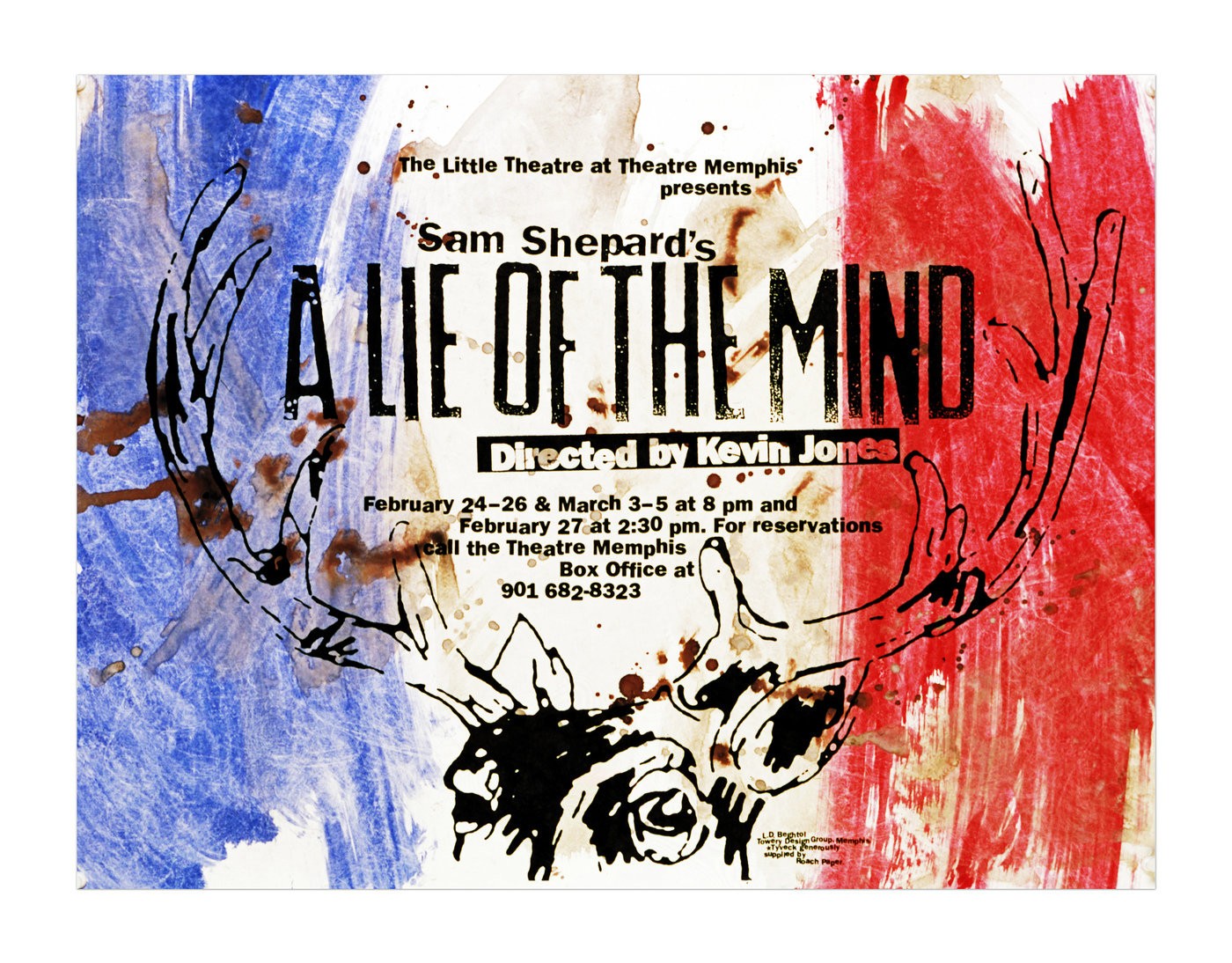

Created for Theatre Memphis’ production of A Lie of the Mind. Painted print with deer blood.

There was no greater admirer or collector of antique photographs than L.D. Friends who followed him on social media are probably familiar with all his “dead boyfriends” — a faded black and white gallery of sturdy 19th-Century fellows with fine facial hair and swell duds. In addition to collecting, L.D. gave his boyfriends stories, and wrote parts for himself.

The photo collection extends beyond dead boyfriends, of course. He collected dead imaginary family and friends too. Now, I’m sorry to say, it’s time to get real. Phil Campbell is a former staff writer for The Memphis Flyer, currently living in Queens. Phil met L.D. in 2010 when he joined me and fellow Flyer alumni Jim Hanas for coffee and drinks in Brooklyn. Following this Memphis publishing reunion, Phil and L.D., formerly two friends of friends, became regular friends and frequent museum buddies. After visiting an exhibit together, Phil, a compulsive memoirist, asked L.D. how he would pose for a photograph, were it the late 1900s and he “only had one real chance in his life to be photographed.”

Without hesitation, off the top of his head, LD answered, “It’d be English summer, 1896 or so: I’d wear a striped Henley blazer; deepish-brimmed straw boater with grosgrain band; round-collard soft-front shirt; four-in-hand silk tie, wide-ish, shortish; white flannels or line trousers, quite narrow, slightly pegged, but no cuffs; perhaps a light vest, possibly knit; lace up high top Oxfords, canvas and leather. Absurd socks — with clocks on them? I’d be photographed with an equally dapper friend (or two) with our bicycles, near a lake or having a little picnic under a plane tree.”

According to Phil’s essay, L.D. would, “pose with a dog, which he does not actually have in the 21st-Century. Its name would be Montmorency.” At last, we’ve gotten to it: This piece of instant art direction is the true and tragic story of my friend L.D. distilled. It’s everything you need to know in order to know everything you need you know about things you should know and all the things that matter.  Robin Holland

Robin Holland

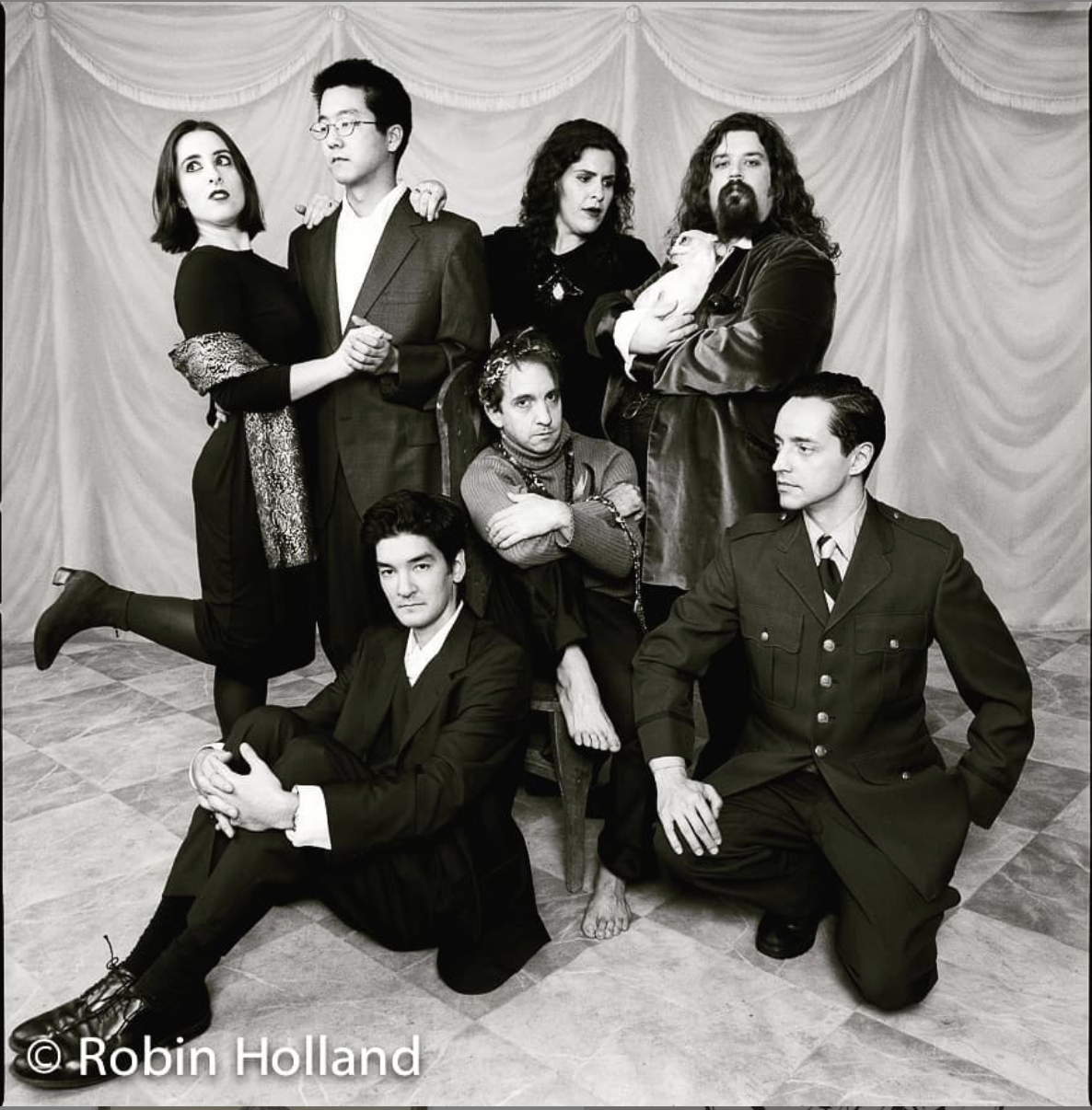

The Magnetic Fields, 69 Love Songs lineup

It’s true, our subject would likely reject even the idea of heartbreak, swearing there was nothing but a great dark hole in the center of his chest. What’s understood about the cardiac event that ended his life suggests L.D. was fibbing on this score. So if you’ve been been hesitant to indulge in feelings, it’s probably okay to lose all cool in your remorse. For all the good it will do you. The heart that failed L.D. was enormous and often full.

If this doesn’t fully allay concerns, one might also frame tributes in the form of small plays, or present them in the style of a beloved author. A little distance goes a long way. “He offered to try to tune my Marxolin once, and I never forgot it,” one admirer posted to Twitter, shortly after the bad news broke. “I guess it’s the small things.”

Of course LD knew how to tune a Marxolin. And of course he offered to tune somebody’s Marxolin for them. And yes, it’s exactly the small things. And the old and fragile things. The forgotten, esoteric things of great power and no consequence; broken, beautiful, and probably without objective meaning. These are the things that mattered. If ever there was a sweet curmudgeon, born to be posthumous, it is L.D. Beghtol. And wouldn’t you just know it, author Mark Dery already claimed “Born to be Posthumous” as the title for his 2018 Edward Gorey biography. I know because L.D., as generous with books as he was with offers to tune Marxolins (and everything else, really), gave my family the hardback edition as soon as it was available. With this anticlimactic joke, about as funny as an urn to the head, our woeful yarn reaches its doleful conclusion. A great spirit has been lost; attention must be paid. Goodnight, dear L.D. And, foiled again!