It was a decade of great change in the film industry, with the digital revolution disrupting both the production and distribution ends, and corporate consolidation increasing its stranglehold on the business end. But there was no shortage of great works from both Hollywood studios and independent producers. Here’s my list of the best of the decade. But first, the worst.

Worst Picture Of The Decade: Dracula Untold (2014)

No movie epitomized the brutal cynicism and rampant executive incompetence that plague Hollywood like this abortive retelling of the Dracula story. Stripped of the sex and body horror that gives the vampire myth its beating heart, this piece of extruded corporate product was meant to kick off a Marvel-style series based on the classic Universal monsters by ripping of the worst parts of the 1999 version of The Mummy. It failed, but they’re still trying to get that series started, most recently with Tom Cruise’s woeful remake of The Mummy. I feel like I never recovered from this deep hurting.

And now, the good films!

25. Short Term 12 (2013)

Dustin Daniel Cretton’s autobiographical story of his time working in a mental health treatment facility for teenagers is the quintessential festival hit of the decade. Its empathetically drawn characters are brought to life by a stellar cast, including debuts by Brie Larson, Kaitlyn Dever, Rami Malek, and Lakeith Stanfield.

24. The Love Witch (2016)

Anna Biller’s cheeky tribute to Hammer horror is the ultimate DIY project. Biller wrote, produced, directed, and edited the film, while somehow also finding time to oversee the flawless production design, create the costumes, and write and perform the score. And did I mention she did the whole thing on 35mm film? In 2016!

23. The Social Network (2010)

Little did we know, in 2010, how big an impact Facebook would have on the coming decade. The final image of David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin’s film, with Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) compulsively clicking refresh, predicts a humanity devoured by its own information creation. We’re living in that world now.

22. Carol (2015)

Todd Haynes’ immaculate adaptation of the 1952 lesbian romance novel The Price of Salt is anchored by a pair of incredible performances by Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. It’s as impeccably crafted as it is gorgeous and moving.

21. Exit Through The Gift Shop (2010)

The 2010s were the decade when the real and the fake finally collapsed into each other. Banksy’s sole director credit bites the hand that feeds it by deconstructing the high end art world with the story of the rise and fall of Mr. Brainwash. The fact that it might have all been a giant hoax just makes it juicier.

20. Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010)

Edgar Wright’s visually groundbreaking hero’s journey bob-ombed on release but gained a cult following over the decade as people discovered how much fun it is. Working from a graphic novel by Bryan Lee O’Malley, Wright’s film is the first to see the world through the lens of a generation raised on video games.

19. Little Women (2019)

I figured Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird would land on this list until I saw her adaptation of Little Women. The ensemble cast of Saoirse Ronan, Emma Watson, Florence Pugh, and Eliza Scanlen as the four March sisters growing up in the shadow of the Civil War, supported by Laura Dern, Timothée Chalamet, and a flinty Meryl Streep, combines with an expertly reimagined screenplay that brings out the contemporary themes in Louisa May Alcott’s novel.

Leonardo Dicaprio as Rick Dalton and Brad Pitt as Cliff Booth

18. Once Upon A Time In Hollywood (2019)

Quinten Tarantino’s sprawling epic of the death of the 1960s stubbornly refuses to be what you think it’s going to be. A Pulp Fiction take on the Manson murders? Nah, how about a buddy comedy with Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt as an aging TV star and his stuntman bestie.

This Is What Love In Action Looks Like

17. This Is What Love In Action Looks Like (2011)

Morgan Jon Fox’s documentary of the protest movement that shut down the ex-gay therapy program Love In Action was the best film made in Memphis this decade. What starts off as a raw and angry story evolves into a pean to understanding and acceptance when John Smid, the head of the operation imprisoning 16-year-old Memphian Zach Stark, resigns and comes out as gay himself. The film, seven years in the making, is a triumph of perseverance and feeling.

Elsie Fisher as Kayla in Eighth Grade

16. Eighth Grade (2018)

Bo Burnham’s directorial debut is kind of a small and unassuming movie, but it is elevated to greatness by Elise Fisher’s stunning performance as a girl dealing with the last week of elementary school. Her Kayla is the poster child for the age of social media anxiety.

Sorry To Bother You

15. Sorry To Bother You (2018)

Imagine Brazil set in a call center and you’re in the ballpark of Boots Riley’s sci fi farce. There are so many memorable moments, like Lakeith Stanfield’s rap debut at a corporate party and Tessa Thompson’s ever-changing earrings that comment on the action.

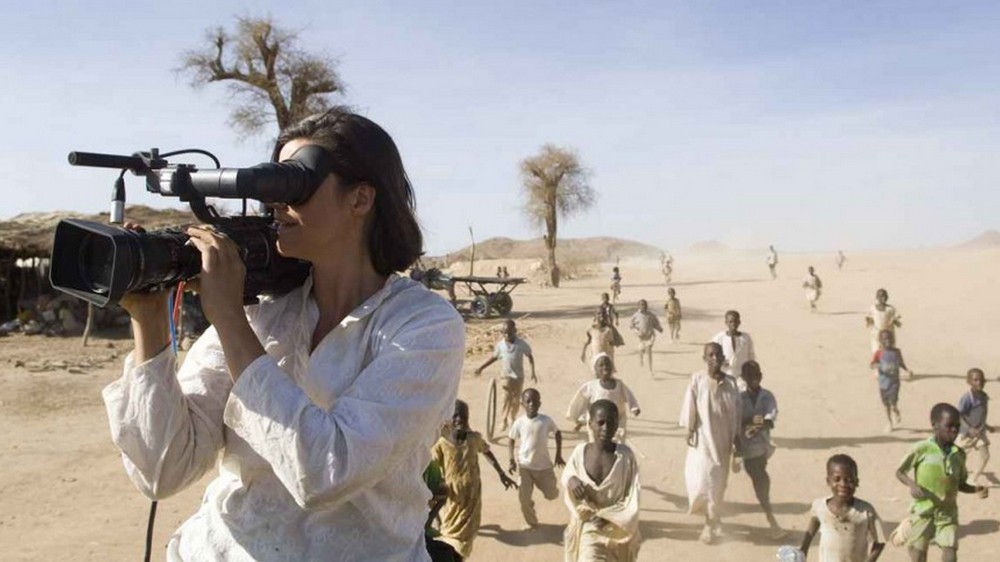

Director Agnés Varda in Faces Places

14. Faces Places (2017)

Director Agnes Varda’s penultimate film was as iconoclastic as the rest of her 50-year career. She partnered with the street artist JR to roam the French countryside, meeting people and creating artworks that were both monumental and fleeting—kinda like life itself.

13. Black Panther (2018)

Ryan Coogler proved himself to be the master of genre this decade. He rose above the bland competence of the Marvel machine with the Shakespearian story of the struggle between T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) and Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) for the throne of Wakanda. But it wasn’t just the fact that we finally got a black superhero that made it great. Coogler’s film has more in common with classic swashbucklers like The Sea Hawk and The Adventures of Robin Hood than it does with modern product like Justice League.

12. Cameraperson (2016)

Kristen Johnson has spent her career traveling the world, shooting documentaries for other directors. She saved the best bits that were cut out of those films and pieced together this collage of tiny slices of her life on the road, from shepherds tending their flocks in war zones to rape victims telling stories of trauma.

11. Paterson (2016)

Adam Driver has emerged as one of the best American actors of his generation, and he is never better than playing a bus driver named Paterson in Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson. Driver is a shy poet in a dead end job who obsessively observes the people around him and loves his eccentric wife Laura (Golshifteh Farahani). The little advances and setbacks in his modest life are blown up to big drama in this life affirming masterpiece from the Mystery Train director.

10. Booksmart (2019)

Not since the Blues Brothers have we seen a comedy team as brilliant as Beanie Feldstien and Kaitlyn Dever in Booksmart. The inseparable best friends have spent their entire high school careers toeing the line and over-achieving. Now, in their last night before graduation, they want to party. Director Olivia Wilde’s perfect film is the best pure comedy of the decade.

9. Inherent Vice (2014)

Was Paul Thomas Anderson’s best film of the decade The Master or Phantom Thread? Nope, it was his little-seen Thomas Pynchon adaptation. The paranoid neo-noir loses the plot in amusing ways as private eye Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) tries to unravel the intertwined mysteries of the disappearance of his ex-girlfriend Shasta (Katherine Waterson, never better) and a cabal of drug smuggling dentists known as the Golden Fang. Or maybe not. It’s complicated.

8. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Wes Anderson’s jewel box of a film sits on the poignant cusp between the death of the old world and the birth pains of the new. Ralph Finnes gives the performance of his life as M. Gustave, the greatest concierge in history, who defends the old hotel against the predations of time and encroaching fascism.

7. Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017)

In the era of Disney dominance, as the corporate stranglehold on the film industry tightened, it was rare to see a singular voice cut through as effectively as Rian Johnson’s did with the middle passage of the Star Wars sequel series. His story examines where the decades of myth-making have gotten us, and offers a vision of a more positive future while giving Mark Hamill’s Luke Skywalker the heroic sendoff he deserved—and one that very few people in the audience were ready for—while sacrificing none of the fun you expect from the blockbuster franchise.

6. Inside Out (2015)

Pixar dominated the animation of the 2000s, but this decade was more of a mixed bag for the studio. Inside Out is Pixar at its most sophisticated, both psychologically and visually. Riley (voiced by Kaitlyn Dias) is an 11-year-old girl whose life is thrown into chaos when her family moves to San Francisco. The real action takes place in her mind, where her personified emotions, led by Joy (Amy Poehler) and Sadness (Phyllis Smith) try to keep things in balance. Inside Out is a beautiful, and important, film.

Choi Woo-shik, Song Kang-ho, Jang Hye-jin, and Park So-dam as a family of grifters in Parasite.

5. Parasite (2019)

Bong Joon-ho’s savage take on class conflict is a perfect film whose reputation will only grow over time. The underclass in his vision of Seoul lives literally in basements, while the top of the economic caste live in constant anxiety and discontent, despite being surrounded by luxury. The twisty, darkly comic plot is kept grounded by a bevy of great performances, the best of which is Park So-dam as the con artisté daughter of a family of desperate grifters.

Yalitza Aparicio

4. Roma (2018)

Alfonso Cuarón’s black and white remembrance of Mexico City in the 1970s is one of the great technical and emotional triumphs of the decade. The director’s peerless vision (he became the only person in history to win both the Best Cinematographer and Best Director Oscars for the same picture) is brought to life with a stunning performance by Yalitza Aparicio, a former schoolteacher who earned a Best Actress nomination the first time she ever set foot in front of a camera.

3. (tie) Get Out (2017) / Us (2019)

I couldn’t decide which of Jordan Peele’s twin masterpieces to include on this list, so I copped out and went with both of them. To me, they feel like companion pieces. Get Out is like Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, a finely tuned, ruthlessly efficient machine. Us is more like Hitchcock’s Vertigo, an exploration of themes and images by a master artist trying to map the psyche of a nation. Both of them are horror films that transcend and transform the genre into something new and exciting.

Mahershala Ali in Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight.

2. Moonlight (2016)

Barry Jenkins is not only one of the best visual stylists of decade, but also our greatest romantic. The three part story of Chiron, a child of Miami’s Liberty City ghetto, is told with three different actors in three different eras of his life. He’s poor, he’s black, and he’s gay, and the film’s focus is his struggle to reconcile the identities that have been placed upon him and become a whole person. Moonlight, a transcendent masterpiece by any measure, features a career-making performance by Mahershala Ali and the most memorable cross-dissolve in the history of cinema.

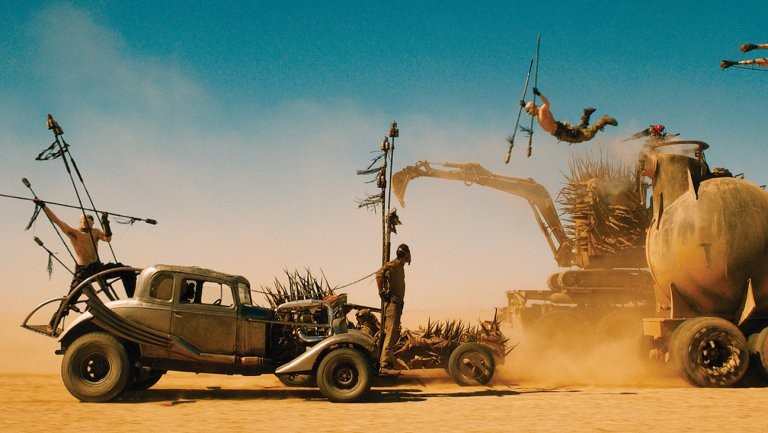

1. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

“Who killed the world?” is the question that hangs over George Miller’s post-apocalyptic epic. Released a month before Donald Trump began his campaign for president, it points a finger straight at a patriarchal capitalism that sacrificed civilization and the ecosystem for short term profit and control. But this is no polemical think piece—Fury Road also happens to be the greatest action films ever made. It’s a direct descendant of Buster Keaton’s The General; Miller described its simple structure as “a chase, then, a race”. The editing by Margaret Sixel will be studied for as long as humans make filmed entertainment. In 2017, Stephen Soderbergh, one of film’s greatest craftsmen, said to Hollywood Reporter, “I don’t understand how they’re not still shooting that film, and I don’t understand how hundreds of people aren’t dead…[Miller] is off the chart. I guarantee you that the handful of people who are even in range of that, when they saw Fury Road, had blood squirting out of their eyes.”

Breezy Lucia

Breezy Lucia  Breezy Lucia

Breezy Lucia  Breezy Lucia

Breezy Lucia  Breezy Lucia

Breezy Lucia