Last weekend’s box office race involved two seeming opposites: Marvel’s Ant-Man and Trainwreck, the collaboration between comedy titans Amy Schumer and Judd Apatow. But after a Sunday double feature of the two films, I was struck by their similarities and what they say about the current risk-averse environment in Hollywood.

Ant-Man stars Paul Rudd as Scott Lang, a former electrical engineer whom we first meet as he is being released from San Quentin, where he was doing time for a Robin-Hood robbery of his corrupt former employer. His wife Maggie (Judy Greer) has divorced him and is living with their daughter, Cassie (Abby Ryder Fortson) and her new boyfriend, Paxton (Bobby Cannavale). Scott tries to go straight, but after he’s fired from his job at Baskin-Robbins, in one of the more creative product placement sequences in recent memory, he takes his friend Luis (Michael Peña) up on his idea to break into a Victorian mansion and clean out a mysterious basement vault.

But, as the comic book fates would have it, the mansion is the home of one Dr. Hank Pym (Michael Douglas), an old-school superscientist who discovered a way to reduce the space between atoms and thus shrink himself down to the size of an insect. For years, he and his wife operated in secret as a superteam of Ant-Man and the Wasp. After a desperate mission for S.H.I.E.L.D. to stop World War III, she disappeared into subatomic space, and he took off his supersuit and vowed to keep the world-changing and potentially dangerous technology under wraps.

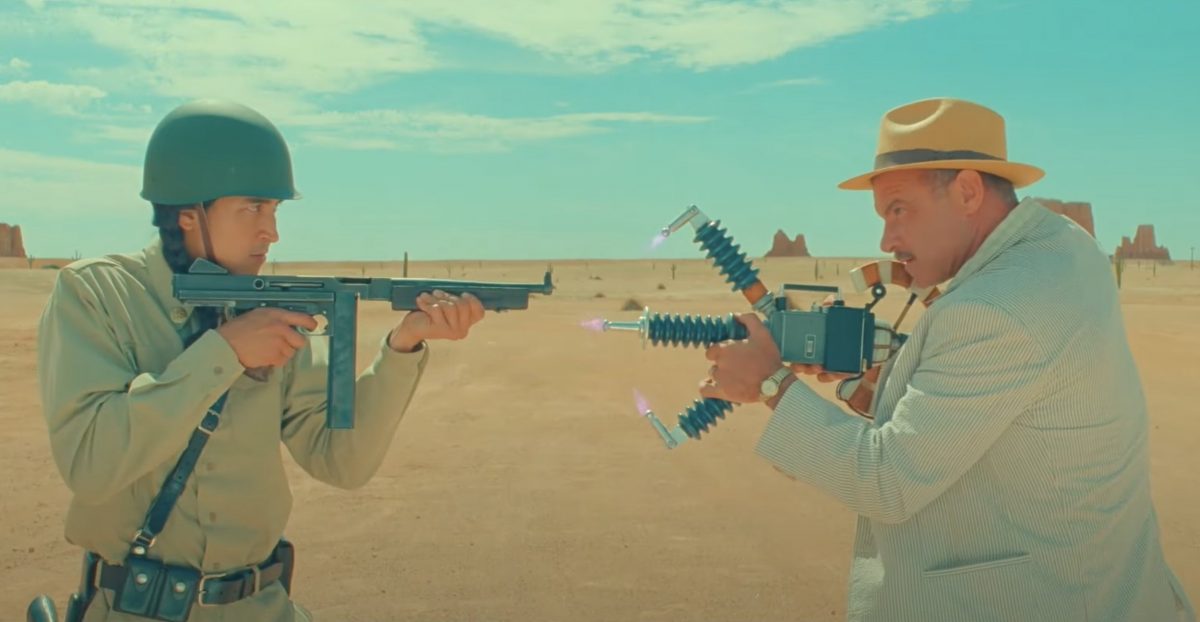

Under Pym’s tutelage, Scott sets out to stop the scientist’s former protegee Darren Cross (Corey Stoll) from selling his own version of the shrinking technology to the evil forces of Hydra by stealing a high-tech Iron Man-type suit called the Yellowjacket.

Ant-Man is not as good as this year’s other Marvel offering, Avengers: Age Of Ultron, but it scores points for originality. Written by Attack the Block‘s Joe Cornish and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World‘s Edgar Wright, who was originally slated to direct, the film tries — and mostly succeeds — to combine an Ocean‘s Eleven-style heist flick with a superhero story in the same tonal range as Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman. It’s burdened with the traditional origin-story baggage, but the sequence where Scott discovers the powers of the Ant-Man supersuit by shrinking himself in the bathtub and fleeing running water, hostile insects, and a vacuum cleaner is another triumph for special effects wizards Industrial Light & Magic. Rudd, a veteran of many Apatow comedies, including Knocked Up, is exactly the right guy to sell the mix of comedy and superheroics, and some sparks fly with furtive love interest Evangeline Lilly as Pym’s double agent daughter Hope van Dyne. For the sections of its 117-minute running time when it’s focusing on its core plot, Ant-Man is a good time at the movies.

For Trainwreck, Amy Schumer’s vehicle for transforming basic cable stardom into a feature film career, she surrounded herself with some very heavy hitters. First and foremost is Apatow, the producer, director, and writer with his fingers in everything from The 40-Year-Old Virgin to Girls. The pair execute Schumer’s first feature-length screenplay with verve. Schumer stars as Amy, a New York magazine journalist who is basically a fleshed-out version of her public persona. In a sharp inversion of the usual romantic comedy formula, she is a quick-witted, commitment-phobic hookup artist dating a hunky man-bimbo named Steven (John Cena), who just wants to get married, settle down, and raise a basketball team’s worth of sons in a house in the country. Soon after her chronic infidelity torpedoes her relationship, she is assigned to write about a prominent sports doctor named Aaron (Bill Hader), who counts LeBron James among his patients. The two hit it off, and she soon violates her “never sleep over” rule with him.

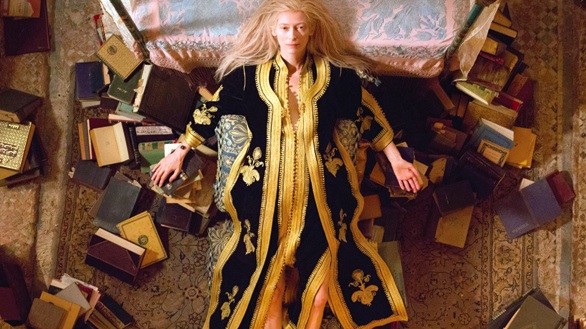

If this were a traditional Rom-Com, and Amy’s character were male and played by, say, Tim Meadows (who is one of the dozens of comedic talents who have cameos), I would be calling him a ladies man. Schumer is practically daring people to expose the double standard by calling her a slut. Her effortless performance proves beyond the shadow of a doubt that she has chops to carry a feature film. Apatow is savvy enough to give her a long leash, giving her scenes time to breathe, selecting some choice improvs, and letting barrages of comic exchanges live in two-shots. Hadler finds himself in the unfamiliar role of the straight man to Schumer’s cutup, but he acquits himself well in what is essentially the Meg Ryan role from When Harry Met Sally. Practically everyone in the film’s supporting hoard of comics and sports figures also gives a good turn. Tilda Swinton is stiletto sharp as Dianna, Amy’s conscience-free magazine editor boss. Dave Attell is consistently funny as a homeless man who acts as Amy’s Greek chorus. Daniel Radcliffe and Marisa Tomei slay as the leads in a black-and-white art film called The Dogwalker that the film’s characters keep trying to watch. Matthew Broderick, Marv Albert, and tennis superstar Chris Evert share a funny scene. But the biggest surprise is LeBron James, who shines with confidence and humor every time he’s on the screen. For the sections of its 124-minute running time that it focuses on Amy’s romantic foibles, Trainwreck is a good time at the movies.

But that’s the rub for both Ant-Man and Trainwreck. They both spend way too much time straying from what an M.B.A. would call their “core competencies.” In the case of Ant-Man, the distractions are twofold. First is the now-predictable, awkward shoehorning of scenes intended to connect the film to the larger cinematic universe. As his first test, Pym assigns Scott to steal a technological bauble from a S.H.I.E.L.D warehouse, prompting a superclash between Ant-Man and fellow Marvel C-lister Falcon (Anthony Mackie). The allegedly vital piece of equipment is never mentioned again.

Second is the turgid subplot involving Scott’s efforts to reconnect with his daughter Cassie, and her would-be stepfather Paxton’s attempts to put him back in jail. When Scott is having trouble using Pym’s ant-control technology, Hope tells him to concentrate on how much he wants to reunite with his daughter. The moment rings completely false in context: If you’re trying to talk to ants, shouldn’t you be concentrating on ants? The intention seems to be to make Scott a more sympathetic character, but Rudd’s quick-quipping charisma makes that unnecessary. Why spend the time on flimsy sentiment when we can be playing to Ant-Man’s strengths?

Similarly, Trainwreck gets bogged down in a superfluous subplot involving Amy’s sister Kim (Brie Larson) and their father Gordon (Colin Quinn). It starts promisingly enough in the very first scene of the movie when Gordon explains to young Kim and Amy why he and their mother are getting a divorce (“Do you love your doll? How would you like it if you could only play with that one doll for the rest of your life?”). But then, we flash forward to the present day, and Gordon has been admitted to an assisted living facility, which becomes a source of friction between the sisters. Quinn is woefully miscast as a disabled old man, especially when he’s sitting next to veteran actor and actual old man Norman Lloyd. The subplot is seemingly there only for cheap sentiment, and it drags on and on, adding an unacceptable amount of running time to what should be a fleetly paced comedy. As we left the theater, my wife overheard a woman asking her friend how the film was. “I like it okay,” she said. “I thought it was never going to end, though.”

When Ant-Man is kicking pint-sized ass and Amy Schumer is schticking it up, their respective movies crackle with life. Hollywood is filled with smart people, and I can’t believe that an editor didn’t point out that the films could be improved by excising their phony sentimental scenes. So why didn’t these films achieve greatness? I submit it is another symptom of the studio’s increasingly crippling risk aversion. All films must be all things to all audiences to hit the so-called “four quadrants” of old and young, male and female, so raunchy comedies get extraneous schmaltz and lightweight comic book movies get weighed down with irrelevant family drama. Both Ant-Man and Trainwreck end up like rock albums with lackluster songwriting filled with killer guitar solos. They’re entertaining enough but haunted by the greatness that could have been.

Ant-Man

Now showing

Multiple locations

Trainwreck

Now showing

Multiple locations