We’ve all been to Tom Lee Park, either before or after its $60 million reimagining transformed Memphis’ relationship to the riverfront. Maybe you’ve seen the statue of a young Black man reaching out from a rowboat to rescue a person in the water. But do you know who Tom Lee was?

On May 8, 1925, the steamship M.E. Norman was sailing upstream on the Mississippi River, returning to Memphis after a day trip to Pickney Landing. For some reason later investigations were unable to determine, as it approached Cow Island Bend, the boat suddenly capsized, throwing 75 people into the rushing waters of the Mississippi. Tom Lee was the boatman on a skiff named Zev, making his living ferrying people and cargo from one shore to the other. He witnessed the accident and raced to the scene, where he started pulling people out of the water. He made five trips to and from the accident site, ultimately saving 32 people — despite the fact that he could not swim. Lee became a nationally celebrated hero, even getting an invitation to the White House to be honored by President Calvin Coolidge. The Memphis Engineers Club bought a house for Lee and his wife, and the city gave him a job in the sanitation department. After he died in 1952, the grassy stretch by the river was named in his honor.

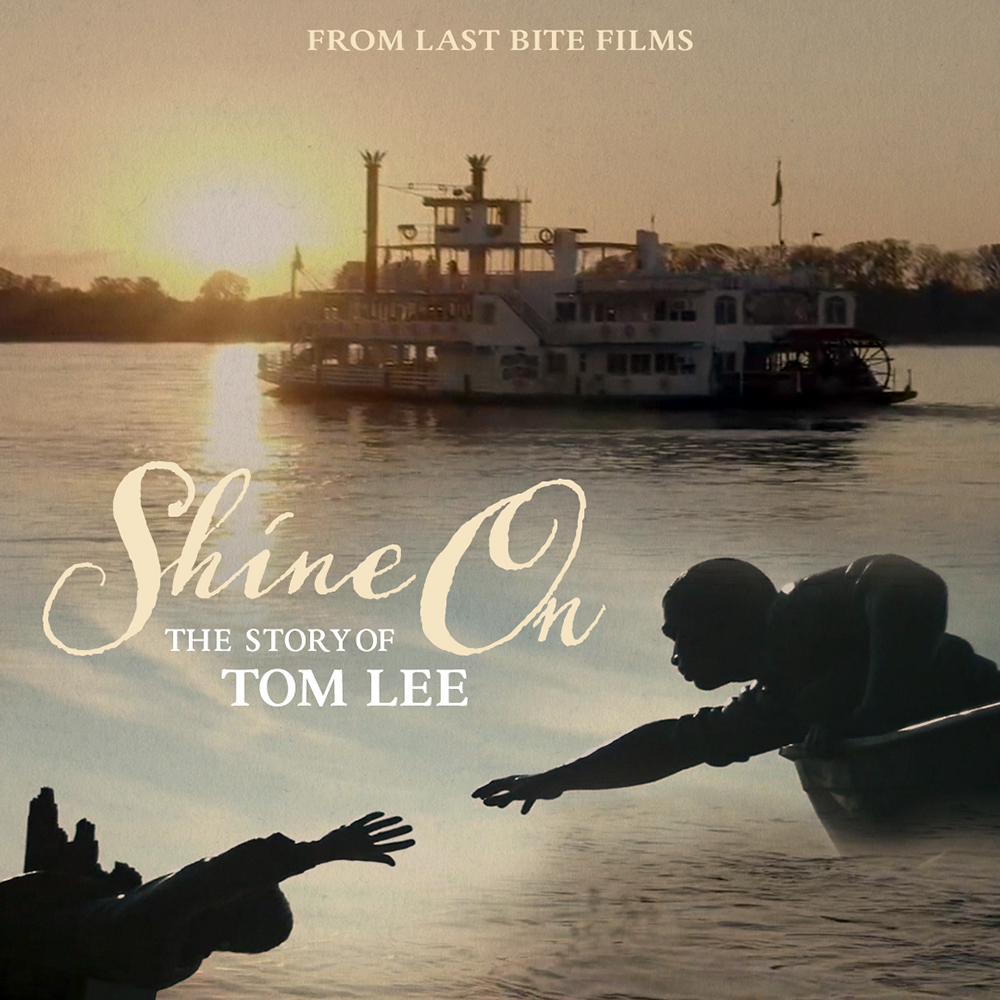

In November 2020, the crew of Last Bite Films was commissioned to make a documentary about the Memphis River Parks Partnership’s Tom Lee Park renovations. “As we were in the process of that, we started to get to know the family of Tom Lee’s descendants,” says producer Joseph Carr. “We just kind of slowly started to realize that there really had not been any documentary or anything, beyond a few articles here and there, that made an in-depth attempt at telling Tom Lee’s story. So we decided during that time that we were going to try to tackle the subject. Initially, we had talked about doing a more traditional documentary, and it sort of just evolved from there based on what we thought we could do, how creative we wanted to be, talking to the family, how open they were to us, doing this in a different manner, and we just got excited with that possibility and kind of ran from there.”

Having just finished a conventional documentary, director Matteo Servente says they wanted to try something different. “We kind of thought about how exciting it would be to make a piece that was not just following those traditional patterns of the talking-head documentary because of the story, because of budget limitations, and also because of our creative need to try something different. We started talking about adding elements that are non-traditional in a narrative or even in a documentary, blending in elements like dance and sound design to a degree that was going to become almost like a prominent part of the piece.”

Amazi Arnett composed the music and wrote the screenplay for what would become “Shine On” “Coming from Tom Lee’s point of view was sort of the product of all of our conversation and what Matteo wanted, and that made sense to me. We don’t hear from him. There’s all this lore about who he is, but no idea about who he was as a person. It was important to me to capture that. Once we talked with the descendants, I started noticing all these little bits of information that the public couldn’t possibly know … I wanted to really ground him in his humanity, and what he would’ve thought about the situation.”

In the film, Tom Lee is played by Kenon Walker. “I think he just was somebody who was in the right place at the right time and decided to do something right,” says Walker, familiar to Memphians as the current Duckmaster at the Peabody Hotel. “I don’t think he set out to be a hero. I think he was in a position where he saw something that needed to be done, and he was in a position to do it … A lot of people today would’ve just sat on the sideline and watched that ship sink. They might not have stepped up and done anything but recorded it, or put it on Facebook Live.”

The film combines voiceover, reflecting on the rescue from Tom Lee’s perspective, with some stunning images of the Zev on the river at sunset, and dance sequences by choreographer Steven Prince Tate filmed in the park. “We shot on the river, and so we had a lot of moving pieces that were not easy to pull off,” says Servente. “We did our homework, but the crew really just brought it home … [Editor] Edward Valibus helped us find the place and the amount of dance that was needed for everything.”

Producers Molly Wexler and Anton Mack raised funds for the film and did the necessary archival research. “It was a fascinating project,” says Mack. “We had such deep and rich conversations as we tried to work through this creative process with Arnett’s writing and Matteo’s leadership.”

“The nice thing is that we’re such a good team,” says Wexler. “Anton and I did a lot of the archival stuff, going through all the records at the library and so on, just trying to make sure we had the story correct. We also brought on Ryan Jones from the National Civil Rights Museum, who helped contextualize the story to make sure we got it right for that era, which was incredibly helpful.”

“Shine On: The Tome Lee Story” aired on WKNO-TV on the 100th anniversary of Tom Lee’s heroics. You can catch it on the PBS streaming app for the next week or so. “This story is really evergreen because as kids go and visit the park, they’ll watch this film ahead of time to give them some context of who Tom Lee was,” says Wexler. “It’s going to be incorporated in some Jim Crow curricula. It doesn’t have to just be isolated to Tom Lee. There’s so much more to it that connects it to the history of the country.”

“Shine On! The Tom Lee Story” is streaming on the PBS app.