A bass-and-drum beat boomed over a party that pulsed around the twilight-and-neon-painted patio of Rock’n Dough.

Pizza scented the warm air. Plastic cups flowed with golden beer. Corn hole bags rattled, flew, and fell home. Balloon animals squeaked in the hands of delighted children. Duck pins crashed occasionally somewhere inside. Laughter and raucous conversation raised high over the entire scene, building a cathedral dome of fun and positive energy.

A new light switch flipped on in The Edge District that Friday night in early May. The once-vacant building (that formerly housed Trolley Stop Market) came alive again and drew scores to its shores for the promise of something new, exciting. The promise was delivered. The energy was electric, especially for that corner of town. But that sort of vibrancy is becoming more and more commonplace there.

New light switches are being flipped on all over The Edge. No task force was formed for its revitalization. No hashtag was blasted on social media. No special study for it was ordered by the Memphis City Council.

That new energy is largely organic. It’s been fueled with years of care and investment by the Downtown Memphis Commission (DMC) and the Memphis Medical District Collaborative (MMDC).

But an ad hoc group of Edge stakeholders is forging the neighborhood, too. They gather and strategize (as they did recently) over a lunch snack of ribs and catfish bites at Arnold’s BBQ and Grill. Ad hoc, maybe, but their members are mighty. Henry Turley Co. The MMDC. Longtime landowners who own and manage key properties in The Edge. If you’ve ever been to Strangeways Wednesday for free food and drink, you’ve experience a portion of this group’s influence. You’ve also experienced their overall mood for The Edge: fun, communal, welcoming, and connected to the neighborhoods around it.

Let’s Go to The Edge

The Edge is just quirky. Its mother might say, “It has character.” And it certainly does.

No one can agree on its boundaries, for one. Not really. Is it Union and Madison from Manassas to Danny Thomas or onto Fourth? Broaden that to capture Health Sciences Park and Jefferson, right up to Victorian Village? No facts exist on this. Only opinions. The Edge doesn’t even have its own Wikipedia page like so many Memphis neighborhoods. Border disputes aren’t new or controversial, though. Just ask a local to define Midtown.

The streets in The Edge perform mind-bending shifts from the traditional city grid. Arrow-straight Monroe terminates in the heart of The Edge, only to curve slightly north where it transforms into Monroe Extended. What? Marshall crosses Monroe in the center of the neighborhood at an angle that defies the city’s parallel street design. Madison flies up and over (for one of the best views of the city) to meet up with its old self on the west side of Danny Thomas. Why? The DMC website says the “odd, zig-zag streets and alleys” were laid out to accommodate railroads in the 1800s.

Those twists and turns make The Edge full of surprises, too. Siri led me to Arnold’s on a recent visit. I arrived. Nothing around but Mutt Island. But Arnold’s was right on the map. I turned and spied a sign with a pig and an arrow on it. I followed it. Through a brick archway, down some stairs, and across a grass lot, I spied another pig sign. I followed it (and the scent of pork and hickory smoke) to Floyd Alley and found Arnold’s. I felt like I’d joined a secret club.

Years ago, Tommy Pacello, the late (and missed) director of the MMDC, gave me a big surprise on a bike tour of The Edge, which even then brimmed with opportunity in his endless optimism. We stopped at a weedy spot on the Madison bridge. He bid me look over. I found a deep, overgrown, urban canyon. From his experience with the successful Tennessee Brewery Untapped project, he said to imagine what could be done down there with some string lights and a few kegs of beer. That abandoned, forgotten canyon became The Ravine years later.

In The Edge, paint and body shops sit cheek by jowl with architect firms, tattoo parlors, salons, arts organizations, souvenir shops, brand-new condos, breweries, the headquarters of one of the city’s biggest homegrown banks, and that huge, gold guitar hoisted high outside Sun Studio, maybe one of the most photographed spots in Memphis. All of this sits just outside the steel canopy of Downtown skyscrapers and the glow of summer lights over AutoZone Park.

For all its quirks, defiant nature, and surprises, one thing is a fact about The Edge: Mike Todd, president and CEO of Premiere Contractors, came up with “The Edge” name. When he first got there, he said the place “was a total wasteland.”

“The Last Place on Earth”

Todd likes and dislikes the moniker “the Mayor of The Edge,” even though he admits it’s kind of true. His company bought Premiere Palace in the 1970s. Even though the area was not even close to up-and-coming, he decided Downtown and the Medical District were good bets. So he placed his.

The auto shops were there, giving credence to the area’s first use and nickname, “Auto Row.” The shops serviced the Downtown community, diminished as it was after white flight following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination years before. Later, officials planned the area for a Biomedical Research Zone (BRZ). Landowners would get rich if they held onto their buildings, Todd says. But they never did because the BRZ never panned out.

But Todd didn’t leave. His company doubled down and bought the Stop 345 building on Madison in 1997. At one time he leased the building to a club called The Last Place on Earth, which hosted Eddie Vedder and Sonic Youth before its eventual close, he says. The trolley project came and took years longer than promised. This closed Madison and killed traffic there forever, Todd says. Tenants moved out but Todd didn’t give up.

“I couldn’t let this place just become this shit place under the bridge,” he says. “So, we ran that place for 20 years as various entities. Los Comales just moved in less than a year ago.”

Scott Bomar was 19 the first time he went to The Edge. His band, Impala, was recording an album at Sam Phillips Recording.

“I thought, man, this is where I want to work,” Bomar says. “Cut to a couple of decades later. Well, that’s where I work now.”

Even back in his teens, Bomar thought The Edge was cool. The automotive factories and auto shops were all there. He loves the new energy, too.

“We have a lot of clients who come in from out of town,” he says. “It’s really great to be able to walk across the street to the wine shop [Rootstock Wine Merchants] to pick up something if we need it, or to go down to French Truck and get a coffee, or go to Rock’n Dough and get food. … It’s exciting that there’s so much stuff down there now that’s walkable.”

The Edge was “quiet” when Anthony Lee first got there back in 2004. Well, quiet during the day, anyway.

“It would activate at night because of the club there, which was at one point 616 Club, and then Apocalypse, and then Spectrum,” Lee says. “Then, it was a strip club. So that one little building used to activate it on weekend nights.”

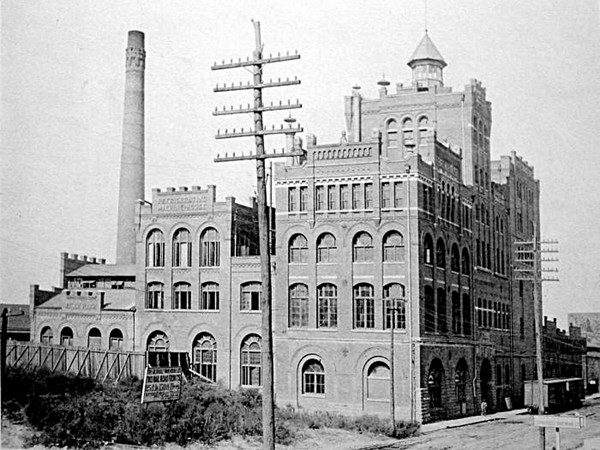

Lee is now the gallery manager at Marshall Arts, an Edge pioneer, founded by Pinkney Herbert. The studio and gallery was converted from an automotive shop, Lee says, just like Sun Studio and many other buildings in The Edge.

“Makers and the craftspeople and the artists kind of converted some of those buildings and [The Edge] took on another quality,” Lee says. “It became sort of like the craft district.

“Pinkney Herbert was probably the first artist that imported that format from New York City. He created Marshall Arts in 1992 with his wife. He saw what they were doing up with there with all those old buildings in SoHo and the Lower East Side and decided to bring a similar idea back to Memphis.”

Lee lists a bevy of artists and craftspeople still working in The Edge with woodworking shops, recording studios, a greeting card studio, and more. With the club gone, he says, the area shares a “two-fold personality” with car maintenance and the arts.

“For years, this was a forgotten neighborhood, but sandwiched by growth in the Medical District and the vibrant Downtown Core, all eyes are now on The Edge as businesses, breweries, and restaurants have all become neighborhood staples,” says the DMC website.

New(ish) Faces

Energy pulsed into The Edge before Orion Federal Credit Union got there. High Cotton opened in 2013, for example, and Edge Alley in 2016. But the Memphis company’s 2019 move from Bartlett to Monroe in the old Wonder Bread factory was a power station large enough to buoy confidence and development in the neighborhood.

“The location in The Edge was chosen when the Orion leadership agreed that the organization could strategically position their corporate headquarters to anchor a historic Memphis neighborhood, end blight, spur commercial and residential growth, and reinforce a critical connection between the Medical District and Downtown Memphis,” says Orion’s board chair Andre Fowlkes.

The Wonder Bread factory sat vacant from 2013 to 2019, making the stretch of Monroe near the building and several surrounding properties “a visible eyesore that could be seen from high-traffic areas including Downtown Memphis and Sun Studios,” the company said in a statement. Instead of tearing down the factory and leveling the block, Orion chose to keep the original shape and bones of the building and added a third story. A new, period-appropriate exterior facade was made of reclaimed bricks from the original building. And, of course, Orion kept that iconic, old-school Wonder Bread sign.

“A better Memphis means a better Orion, and the headquarters move to The Edge was our commitment to the city,” says Orion CEO Daniel Weickenand. “A strong city core can create a ripple effect for development and energy throughout the region. We’re proud to be a part of that.”

That ripple effect is real (just check our sidebar with a list of all the new businesses and real estate developments). The energy is clearly there. Chef Joshua Mutchnick saw it and grabbed on tight. His JEM (Just Enjoy the Moment) restaurant opened in The Edge in April.

“Since day one, we had our eyes on The Edge District because we saw it as this up-and-coming neighborhood that has some iconic landmarks in it, like Sun Studio, Sam Phillips Recording, the Edge Motor Museum,” Mutchnick says. “It has so much potential and we feel very lucky to be a part of that, and that we got on the boat before it left the harbor.

“There was concern once we saw Orleans Station being built. We were like, ‘Maybe we missed the ship. It’s too expensive or we’re getting boxed out,’ but we nailed it.”

Sheet Cake Gallery, a contemporary art gallery, opened on Monroe late last year. Its owner, Lauren Kennedy worked closely with MMDC and DMC on many art projects through her work as executive director of the UrbanArt Commission.

“I was familiar with all of the work and investment they have been making in The Edge, and that felt like something I wanted the gallery to be apart of,” Kennedy says. “The support I have felt from both groups from when I first started looking at spaces through to being open has been incredible for me. Everything has felt just right.”

When asked what drew Memphis Made Brewing Co. to open a new taproom in The Edge, co-founder Drew Barton says the answer was simple: Tommy Pacello.

“When we told Tommy we were looking for a bigger production space, he immediately began telling us about every space in The Edge he could think of,” Barton says. “It didn’t take long after that to find our new spot. We walked into what is now the production space and knew it would be perfect for us.

“At that point we didn’t even know about The Ravine. Once we heard more about the massive outdoor space tucked away in The Edge, we couldn’t wait to open a taproom with The Ravine being our backyard.”

As for when that taproom will open, Barton says, “We did end up having to wait a little while during the pandemic, but we are aiming to have the taproom open in late July.”

Leaders

At least three groups look after The Edge: the DMC, the MMDC, and that group of local stakeholders. (An Edge District Association is listed on the DMC website, but the link to the group takes you to a foreign football gambling site with the URL northcountrycremationservice.com.)

The DMC has for years offered a host of incentives to spur growth in The Edge and throughout Downtown. It offers tax breaks, loans, grants, and other programs to promote the vibrancy of all Downtown.

The MMDC is in its eighth year improving and transforming the Medical District for some of the city’s biggest medical anchors like University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare, and Regional One Health. The group’s quiver of incentives helps people improve their properties, recruit new businesses, create new signage, and more. MMDC has invested $2 million in grants alone since its inception.

More than 20,000 people work in the 700-acre Medical District. But less than 2 percent of them live there. MMDC president Rory Thomas says most people would want to live close to where they work, “but if you don’t have the right housing stock and supply, that becomes a challenge.”

Bridging this gap is now a strategic objective for MMDC. Thomas rattles off a long list of new-ish, available apartment buildings — Orleans Station, The Rise Apartments, The Tomorrow Building headed for the Cycle Shop — all of them in The Edge. Fill those with professionals or students from the many medical organizations and The Edge would buzz with new foot traffic that could then drive new business recruitment and overall improvement of the commercial corridors there.

The DMC and the MMDC work closely together on all of this and more, Thomas says. They both work with that less formal group of Edge stakeholders that met at Arnold’s recently. This group (which featured members of the MMDC that day) has eyes on the bigger picture but also focuses on more on-the-ground issues.

How can we make The Edge more walkable and connected? Could Memphis Brand do a “We Are Memphis” billboard for the neighborhood? Should we make flyers with a QR-code link to an events calendar that we hand out to visitors? All of it to promote the neighborhoods, connect them, and bring more folks in.

Alex Turley, CEO of Henry Turley Co., praised the success of other Memphis neighborhoods like Cooper-Young and South Main. But he says The Edge, the Medical District, and Victorian Village have something those neighborhoods don’t: a major employment center.

“One of our goals was to create a seamless connection from those institutional buildings right into a neighborhood,” Turley says. “That informed the scale and the design of what we built at Orleans Station.

“You have Victorian Village and The Edge. There’s this opportunity to help populate this neighborhood. You already have an established brand for a neighborhood. But how do we get those people who work and go to school in those institutional buildings to come across Manassas? That’s what we keep hearing. They say, ‘We never come across [Manassas].’”

“Wasteland” to Next Big Thing

Remember when South End didn’t have a name? It was vacant, derelict, and spooky, according to some. Remember those blighted warehouses? Now think of how busy it can be at Loflin Yard or Carolina Watershed. Now think about all those apartments — completely filled — where those spooky, old warehouses used to be.

It’s a familiar cycle now if you think of South Main back in the 1990s or Broad Avenue a decade ago. The Edge could be next.

Energy continues to build there and energy has a way of attracting more energy. Big pieces are in place. Optimism is high. Leaders are motivated. And it truly is a community effort in The Edge.

“A win for one is a win for all,” says Meredith Taylor, communications and engagement associate with the MMDC. “Talk to the businesses in The Edge and they’ll say one reason they decided to choose it for the roots of their business is that they feel supported by one another, that when they succeed, all the other businesses succeed as well.

“I do think that’s something that’s very special to The Edge District. I think The Edge is a good backdrop to create and build on the sense of place that’s already existing.”

… … … … … … … … … …

New Neighborhood Businesses Opened or Announced:

• JEM

• Rootstock Wine Merchants

• Inkwell

• Ugly Art Co.

• Sheet Cake Gallery

• Contemporary Arts Memphis

• HOTWORX – Edge District

• Rock’n Dough Pizza

• French Truck Coffee

• SANA Yoga

• Lavish Too A Luxe Boutique

• Memphis Made Brewing Co.

• Flyway Brewing Company (announced)

• Cafe Noir (announced)

• LEO Events

• Hard Times Deli (announced)

Real Estate Developments:

• Orleans Station – 372 residential units, 16,000 square feet commercial space

• University Lofts – 105 residential (micro) units

• The Rise Apartments – 266 residential units

• 757 Court – 45 residential units, 2,400 square feet commercial space

• 620-630 Madison – three residential units, 8,700 square feet commercial space

• Tomorrow Building/Cycle Shop

• 616 Marshall/Inkwell/Ugly Art Co.

• Revival Restoration (rehab) – 12,270 square feet commercial space

• 433 Madison – 2,922 square feet commercial space

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks