Swamp Zen

Tony Joe White’s mastery of self-awareness.

Tony Joe White doesn’t have a disco album from the ’70s. Techno, dubstep, and a million other musical fashions have floated down the river of time without so much as a nod from the Swamp Fox.

“I had a really good thing happen to me at a young age,” White says. “That was to try to be real. Not to try to write for radio or an artist or whatever. Just write what comes out of your feelings and your gut.”

White has a signature sound as a blues guitarist, singer, and especially as a writer. His biggest hits “Polk Salad Annie” (most notably covered by the King of Rock-and-Roll) and “Rainy Night in Georgia” (by Brook Benton) are staples of the funky, Southern sound. White’s latest record, Hoodoo, follows the enlightened path and with serious results.

Tony Joe White

“The thing about this album, it came into the blues charts in London at no. 1,” White says. “I’ve never had a no. 1 album. That’s given us courage. Let’s keep it this way. Let’s keep it simple. When I’m overdubbing my guitar or harmonica after you lay down the bass and the drums, the first thing you want to do is play too much. Licks just start popping out of your fingers. You listen to it back, and you say, ‘Okay, I’ll half this. Then I’ll half that. And then I’ll have found the truth.’ It works that way with guitars or any kind of musical thing, I think.”

Listeners will notice an unfinished aspect to White’s lyrics that give the songs a dramatic ambiguity.

“I think it just happens when I’m writing,” White says. “I’ve always considered the swamps to have a little mystery to them. After the thing is finished, and I lay it down, if it comes out that way, that’s all right. I’ll just leave it. There’s no need to tell everybody everything. It kind of goes along with the swamp stuff. When I’m writing, I don’t really think about anything like that.”

White writes what he knows.

“I was raised in a place called Goodwill, Louisiana, on a cotton farm down by the swamps, delta river swamps,” White says. “My dad and mom, five sisters, and an older brother, they all played. So I heard guitar, piano, and singing all them years growing up down there on the river. I always just enjoyed sitting and listening to them on the porch or wherever, because I never really did get into it to play. I just enjoyed listening. It was mostly gospel and country type songs. And then my brother brought home an album by Lightnin’ Hopkins. I heard that. I was 16, and I said ‘Oh, man.’ So I put my baseball glove up and all the other stuff I was going to be. I started getting dad’s guitar in my bedroom every night, learning those blues licks — a few of them to get by on. My dad has shown me a couple himself. He knew one or two. Lightnin’ was the one who kicked me into the guitar real hard.”

Finding inspiration was not a simple matter, though.

“Most of the kids on the river down there, on the farm, lived way apart, a mile apart probably,” White says. “You’d go see somebody and hang out. They’d have a new record. Late at night on the radio, there was always John R. and Randy’s Records. That’s all they played. Man, I’d lay in that bed and listen until two in the morning knowing my dad was going to get me up at 5:30 a.m. to go hit the cotton fields. I’d go, ‘Oh, man, one more song.’ It was a molasses type time back through there. Wasn’t no hurry. You’d work and then we’d play music. It was hard work. But looking back, it’s all fun.”

As fun as it was, White made quick work of performing and writing on a professional level.

“I got out of high school. Me and my drummer had played a few house parties, this and that. They’d pass the hat around and you’d make 2 or 3 dollars. Then all of a sudden there was this club in Monroe, Louisiana. I don’t even know where they’d heard us. Maybe they came to one of the school parties. Anyway, the co-owner wanted us to come over and play one night. We ended up six nights a week playing for a year in that one place. It was, I think, $20 a piece a night, and we thought, ‘Man, we have finally hit it.’ That’s when I realized, that’s what I do. And from then on, even before I played and got established, that’s what I was going to do. I never thought about starving or not making it. Nothing. I rolled, and I tried to play. When I left Monroe, Louisiana, some guys came from Texas — Corpus Christi. They wanted us to come down there and play their club. We ended up playing two years. It was one of those clubs with chicken wire on the side of the stages and some kid popping you with a beer bottle or something. It was a pretty wild old club.”

White’s success as a songwriter came almost immediately.

“I heard a song on the radio right along that time. It was by Bobbie Gentry, called ‘Ode to Billie Joe.’ I heard that, and I said, ‘How real.’ And I thought, ‘I am Billie Joe. Man, I know that life. I’ve picked that cotton, and I’ve chopped and swam in that river.’ So I decided that if I ever wrote anything, I would try to write something I knew about. I was getting tired of doing all blues onstage,” White says. “Within two months after I had those thoughts, here comes ‘Polk Salad Annie.’ I ate a bunch of polk salad growing up on a farm. And I knew about gators. And then a week later — I’d say it was that close — ‘Rainy Night in Georgia.’ I had left high school before Texas. I didn’t finish high school and went to Georgia to live with my sister and her husband. I drove a dump truck for the city for about a month. Whenever it rained, I wouldn’t have to go to work. I’d sit home and play my guitar all day or all night. So in Texas, I got to remembering some of those old rainy nights, and here that one came. And the rest of them are almost chronicles of humans, people, and things that I knew down in Goodwill, Louisiana, in the swamps.”

White loves hearing the new versions of his tunes.

“That’s always been one of the coolest things for me,” White says. “Here’s someone else who’s all of the sudden jumped up. Like with ‘Rainy Night,’ we’ve probably got 170 versions of that. Then Boz Scaggs in Memphis pops it out, and I bet you I’ve played it 100 times. I had no idea he was even going to do that. They sent it to me, and I said, ‘Oh, man!’ So sometimes, sometimes they surprise me with it.”

Since White professes to know what he’s talking about, it’s fair to ask if there was a real Polk Salad Annie.

“There was about three girls down along that river who could have been Polk. There was one who was … yeah. It could have been her. No names.”

»

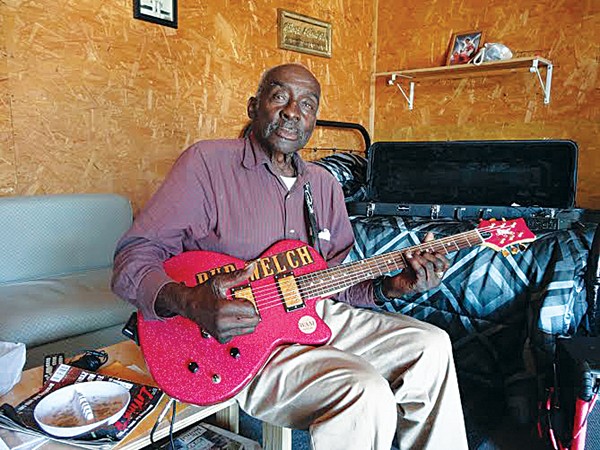

Leo Bud Welch

Linking gospel and blues into one tight chain.

“Hard working man,” Leo Bud Welch said of himself and his 82 years. “I did some hard work in my life. I needed something to come along easier for me. Thank God, I got it going.”

Welch has it going all right. This year, his first CD, Sabougla Voices, got attention from NPR, and he worked on a film in New Orleans with Ryan Gosling. The gospel bandleader and bluesman is planning a tour of Europe and getting ready for his sets on Saturday at the Beale Street Music Festival. Welch’s blend of the spiritual and the secular seems to make perfect sense, in spite of the anxieties that other musicians faced as they crossed the great divide from the choir to the juke joint.

“Blues ain’t nothing but somebody’s life,” Welch says. “Just like the Bible telling the story of Jesus Christ. Blues is life. It’s about how hard you worked down through the years. Whether you got a girlfriend, y’all are liable to be on bad terms. Or your wife. Whatever. Blues is just explaining about life. Life on this earth.”

Welch has found some due recognition for a life spent in gospel music with his group the Sabougla Voices (the “ou” pronounced as in “know”). That group is from his lifelong church, the Sabougla Missionary Baptist Church, south of his home in Bruce, Mississippi. He hosted a gospel music show on a local television station. Welch also has a blues band. But much of his life was spent in the region’s logging industry.

“I run the chains. I cut timber,” Welch says. “I told my wife that if I had a dollar for every tree I trimmed off, I’d be a millionaire today. I called it a one-man band: the one-man saw. I mean, I cut a many a timber. I did that for 35 years. Right here in Bruce.”

Bruce, Mississippi, has a motto: “Where Money Grows in Trees and Hopes and Dreams Never Die.” The town of 2,000 people is currently home to seven logging companies. Timber was an essential asset of Mississippi, dating back to the Chickasaw tribe. The industry grew with the development of the sawmill and exploded with the advent of the railroad. E.L. Bruce was a hardwood-floor magnate, who later started Terminix to keep the termites out of his floors. In 1924, the E.L. Bruce Company set up the town of Bruce to service its lumber needs. It’s said that the whole town ran by the sawmill’s whistle. By the 1950s, Welch was spending less time with his guitar and more time with a chainsaw.

Leo Bud Welch

“It was mostly hardwood. We’d go over to the Delta and cut on the banks of the Mississippi River. All that. We’d cut trees right on the bank and they’d throw those tops in there and they’d have to go get them, you couldn’t leave all those tops in the water,” Welch says. “What we’d do is go down there on Monday, and we’d stay until Friday night when we’d come back to Bruce. We’d have a cook down on camp. Somebody’d cook. We couldn’t see when we’d go, and we couldn’t see when we’d come back. We worked from dark to dark. It got so I couldn’t see how to notch a tree.”

During his time on the logging crews, Welch still played in church. But even that had not always been acceptable.

“Back in them days, they didn’t hardly allow guitar in the church,” Welch says. “It was the devil’s work. You carry a guitar in there, and they say you’re sinning. Now, church don’t sound like that. Back in them days, they’d hardly have a piano. They might have an old piano, and somebody’d be — I call it peckin’ on it. Wouldn’t sound too good to me.”

Welch knew what sounded good. He played all sorts of music before he went into logging.

“I’ve been playing about 60-some-odd years,” Welch says. “I watched my first cousin. His name was R.C. Welch. He had a guitar, and me and his brother played on his guitar. We played around the house. And when I got big enough, we’d play in houses, at picnics. Picnics, like a three-day picnic out in the woods: ball games for three days straight, a picnic for three days straight. There would be a big crowd when different ball teams would come play ball. We mostly played at house parties. Some would call it [a] house dance or whatever. That’s when I started out. It was just me and my first cousin. There’d be others who came there to play. But they always wanted us to play. In other words — I’m not bragging — they were not as good as we were.”

Welch has never run from the blues, and he worked as a musician before he began logging.

“I played in clubs. I organized some guys in Grenada in a band called the Joy Jumpers. Walter Farmer played a steel guitar,” Welch says. “I played with different bands. We did a broadcast in Grenada at the hotel. It was 1400 on the radio dial. That was back in the 1950s.”

But the logging work put a stop to that.

“Now I wasn’t going out and playing at house parties late at night,” Welch says. But he kept his church music moving.

“Later on, I joined a gospel group here in Bruce called the Spirituales. I played lead guitar for them and sang a few songs. Then my sons were playing with me. They were about 16 or 17. I named that band Leo Welch and the Rising Soul Band,” Welch says. “We played places like the Cotton Patch in Tupelo. Down in Batesville, over on the river; we used to play up between Oxford and Holly Springs, a place they called the Barn. We used to play all up in there. We played all around. Our pastor would go out in the street and want the choir to go with him to sing. Nobody would go, except for me, my sister, and my sister-in-law. I named that group Leo Welch and Sabougla Voices. That’s what’s on that CD.”

While some African-American artists faced self-doubt and even public scorn over playing blues in what is still a religiously conservative society, the blending of secular and spiritual does not bother Welch.

“I’ve belonged to that church ever since I was young,” Welch says. “They built it for a school out there on that 16-section land. But somebody decided to go to having church there. It’s down south of here in Calhoun County, down the Number 8 highway. That’s the only place I went to school. I had to walk to school in the mud and in the water. Mud up to my ankles some times. I had those cut off boots. Raggly looking with patches all over them. Everything was great back in them days. More great you might even say than it is now. Everything’s gotten modern now. It’s going the modern way. They kept asking me about playing for the church. In the long run, they elected me to be an officer of the church. Of course I’m a deacon of the church in Sabougla. But since we’ve been going out playing, I tell them I’m going to be there when I can be there.”

I ask if he ever preached. He falls out laughing. Welch is passionate about gospel music and breaks into any song he hears in his mind, playing it finger-style on his pink guitar. He has the same infectious enthusiasm for blues, eagerly and happily playing the shared songs of his place and time.

“I don’t see where there’s no devil in the blues,” Welch says. “They do more devilsome things than that. Oh yeah.”

Leo Bud Welch plays at 3 p.m. at the Blues Shack at the Beale Street Music Festival on Saturday, May 3rd. His album Sabougla Voices is available on Fat Possum Records.

»

Beats Antique

There are hundreds of ways to drop a beat.

Beats Antique is a lot of things. Easily categorized is not one of those things. They use synths, and you can dance. That lands them in the nebulous realm of electronic dance music. But, there’s a belly dancer. There’s a cümbüş, which is a Turkish banjo. There are all sorts of things from all sorts of places. If they defy categorization, that’s categorization’s fault.

Beats Antique is the featured artist for Beale Street Late Night at the FedEx Stage, right after midnight, following Saturday’s line up.

“Personally, I feel that one of the reasons that has happened is that it’s really hard to figure out what we are at all,” says Zoe Jakes, belly dancer and mother goddess to the Beats Antique universe. “It’s funny. What happened the other day, which cracked me up, when someone showed me a guide to Steampunk. It was this book, and it had all of this music that Steampunk people listen to. It had country and rap and then it says ‘other.’ And Beats Antique is under ‘other.’ It’s so funny to me. I guess it’s just hard to figure out where we fit. I feel like for the lack of a better place to fit us, we fall into the ‘electric’ idiom.”

But to a band that has traveled the world in search of direct musical experiences, that’s a pretty frustrating situation.

“We definitely have some aspects to us that are of that [electronic] genre,” drummer Tommy Cappel says. “But mostly we just mess around with synths and stuff like that. I feel like that’s where that comes from. But I’ve played drums for 30 years. Most of [our music] is actual instruments.”

But Beats Antique is not hanging their shingle on using real instruments to attain their sound: a hodgepodge of cultural music ranging from the Hindustani classical to Afrobeat, to Middle Eastern folk. They take pride in collaborating with masters of the forms they use and in recording live, acoustic performances that are later remixed as part of the live act.

Beats Antique

“We have a song, ‘Kismat,’ with Alam Khan,” Cappel says. “He is the son of Ali Akbar Khan, a famous classical Indian sarod player. We invited him down to the studio, and we wrote a track together. We recorded his beautiful playing. So a lot of the stuff is live. We try not to use loops. For the most part, we pride ourselves in recording everything and cutting it all up and making it crazy. Including a 30-piece orchestra.”

It took some adjustment to get the balance right for a stage show, which is ironically where the project began. Producer Miles Copeland grew up in the Middle East. He and his brother, Stewart (of the Police), were children of American and British intelligence officials and spent part of their childhoods in Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon.

“He lived in the Middle East for a few years when he was a kid,” Jakes says. “So he has this love of Middle Eastern dance music, which came out when he was able to create a pet project that became a touring dance company that I was a member of.”

Copeland formed the Bellydance Superstars in 2002. When Jakes began to dance for them, she and her boyfriend and fellow founding member David Satori approached Copeland about making music for the project. Cappel had played drums with Satori.

“We were making songs for Zoe to dance to and for others to dance to, specifically for the tribal-fusion belly-dance world,” Cappel says. “In doing that, we got asked to play live. We wondered how we were going to do that. So we started deejaying our songs, because — if we were to bring out the entire band, that would be like 30 people. It doesn’t make sense. Then we decided to make it a little more live. We added live drums. Even when we were deejaying, David was playing violin and guitar and Turkish banjo, some of the melodic instruments. We added the live drums to it and took out some of the drum tracks from our DJ set. And it’s just come from there into a much more live experience. But you’ll only see three of us on stage. We’re deejaying some of the tracks and playing along with them. It’s definitely a hybrid.”

“I think that how we perform live took a while to find a groove,” Jakes says. “It really was trial and error. Our music, the albums, the way we present it, is this intermingling of live and electronic. That is really what our sound has become: a nice blend. So it feels a lot earthier than the typical dance music.”

The intermingling of cultural and musical influences also puts the group into uncharted territory.

“There’s a lot of folk culture involved in this music,” Jakes says. “People have been playing this stuff for hundreds and hundreds of years. It’s not performance in the sense of what you’re seeing now. It’s not someone getting onstage and dancing to the music. It’s families playing for each other, the mothers and the sons dancing. It was more of a folk and family tradition in small villages. It has a form, and of course it has become more of an entertainment thing over the past hundred years. This has been Egyptian and Middle Eastern dance and an American style of music going back and forth for 100 years. So it’s this total hybrid of folkloric culture and dance with American showbiz.”

From their perspective, they see more hybridization of musical traditions and see their work as part of the great cultural exchange of globalization.

“As Middle Eastern music and music from the East is influencing so many American artists, it’s getting more and more conservative in the Middle East right now,” Jakes says. “It’s very religiously conservative. Belly dance is illegal in a lot of the countries from where it originated. It’s very strange.”

Cappel enjoys cross-cultural feedback.

“When you go to other countries, you realize they all listen to techno,” he says. “Some of the folks who come up to us at our shows may not be from here or may have lineage from other countries. They really like the fusion that’s going on and love to hear those styles represented in popular culture. So we’re giving them a little hybrid of what their culture did.”

Beats Antique plays at 12:15 a.m. on Sunday as the featured artist for Late Night at the FedEx Stage, the finale to Saturday’s lineup.