A sculpture and a fountain, River Man by the local artist John McIntire stands in the contrapposto pose simultaneously drinking a beer and peeing, the 2022 piece depicting a friend’s party-trick from the 1960s — that of the “human fountain.” The sculpture has been shown in Matt Ducklo’s Tops Gallery, a cheeky little thing, but even he didn’t know the source of McIntire’s inspiration at first. “He didn’t want to say it at the time,” Ducklo says. “But it’s based on [Kenneth Lawrence] Beaudoin.”

Ducklo has been interested in Beaudoin for a decade or so, the poet who’s been called “Forgotten ‘Poet-Laureate of the Mid-South.’” “ I started to think about him more after McIntire made that sculpture,” he says. And, now, as of December 2024, Beaudoin’s work — his poetry combining the visual with the literary — is on display in Tops’ “In the Hands of a Poet,” co-curated with artist Dale McNeil.

Like McIntire, Beaudoin was big in the counterculture scene in Memphis during the mid-20th century. He hosted literary salons out of his own home, created the Gem Stone Awards for poetry, and was one of the founders of the Poetry Society of Tennessee. He knew writers like Tennessee Williams, Jonathan Williams, William Carlos Williams, e.e. cummings, Randall Jarrell, and Ezra Pound. By day, Beaudoin was a clerk for the Memphis Police Department for nearly three decades. “My police job kept me close to human beings in tense situations,” he once told The Commercial Appeal. “From a poet’s point of view, it was perhaps the most important job I could have had.”

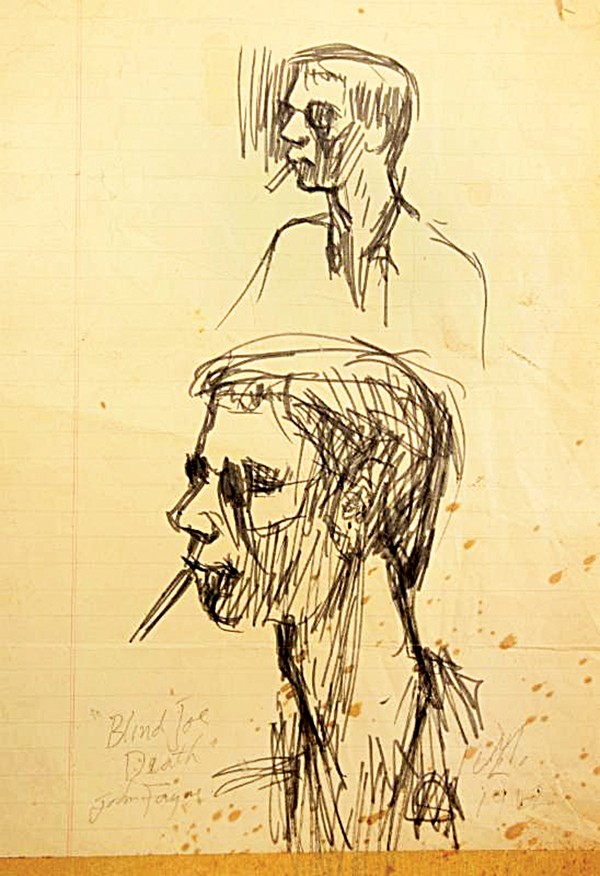

It was at his clerk’s desk — and his home — that he worked on his “eye poems,” collages of words and images from magazine cut-outs. “He would just sit in the middle of piles of magazines and books, cutting, gluing, and smoking,” McIntire said in a press release.

The result is something, as Ducklo says, “meant for the eye as much as they’re meant for the head.” The poems themselves are succinct, their visual pleasure subverting the capitalist and consumerist trends promoted in these magazines — magazines Beaudoin sliced and rearranged for his own purposes, an act itself another subversion.

Beaudoin created thousands of these eye poems and frequently gave them to friends and peers. Many of them — and other forms of his poetry — were widely published in small journals in his lifetime. Today, though, his poetry is out of print, including even his most comprehensive work, Selected Poems and Eye Poems 1940-1970.

This exhibit, in a way, serves as a reintroduction to the largely forgotten poet. After 10 years wanting to show Beaudoin’s work, Ducklo found someone wanting to sell their Beaudoin collection and, with his co-curator Dale McNeil’s Beaudoin poems, had enough for this show. Together, they also created a book that is currently available for purchase at the gallery. (You can also purchase it here.)

Beaudoin stopped creating his eye poems after going blind in the 1980s. He died in 1995.

“In the Hands of a Poet” is on display through March 1st.

Tops Gallery is located in the basement of 400 South Front St. The entrance is on Huling. The gallery’s hours are noon to 4 p.m. on Saturdays and by appointment.