I remember the exhilaration that came with the snap of the match head on the striking surface and the first whiff of sulfur. I remember the thrill as the flame attached itself to a small pile of leaves and twigs and then spread to the larger pieces of kindling my friends and I had pulled from the very clubhouse we sat in. The smoke was mesmerizing, and then it seemed too much. And then there was the shouting of my mother from the back door and her voice coming closer. The look on her face is probably what I remember most and the clenching of my stomach later that night when she made me recount what I’d done to my father.

We’ve all done it — played with fire — or something equally thrilling and frightening. First kiss. First drink. First puff. Rites of passage. It’s the dawning of the unknown, a corner turned abruptly from childhood to adulthood.

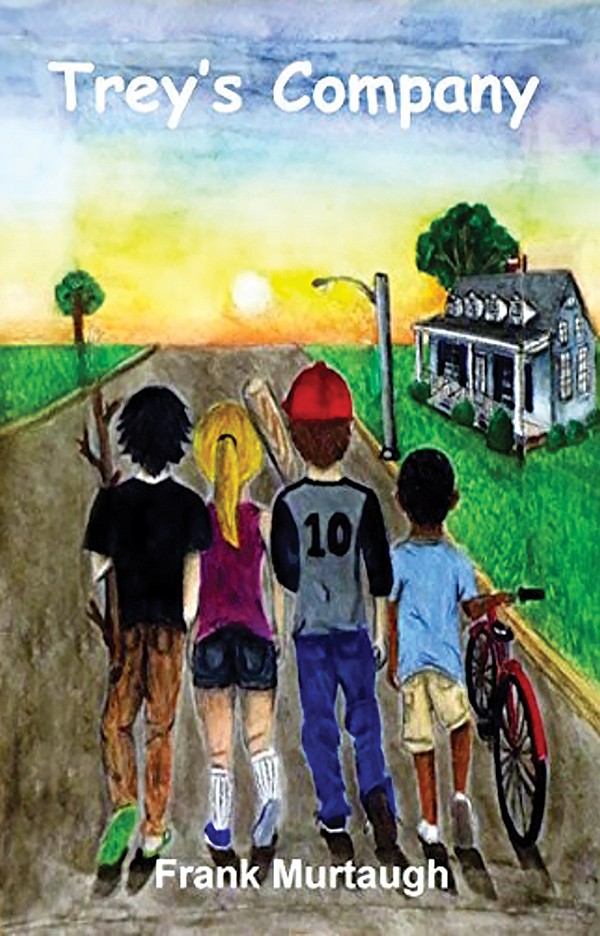

It’s a moment in time, this transition, and it’s one captured in Frank Murtaugh’s debut novel Trey’s Company from Jackson, Mississippi-based publisher Sartoris Literary Group.

Trey Milligan is 13 years old in the summer of 1982, three months that will change him and his world irrevocably. He and his little sister Libby have a tradition of the season spent with their widowed grandmother outside Cleveland, Tennessee, far from their parents in California. The Milligans have traveled around; the parents, who remain distant and unseen throughout the story, are professional academics. But Trey feels most at home among the gently rolling hills of his grandmother’s neighborhood with its meandering creek, adjacent trailer park, and driveway basketball hoops.

It’s the home of some of his dearest friends as well — Devon, Larry, Arline, and Wendy. Wendy. We all have that someone in our lives who lit a fire in our hearts for the first time and changed who we are for good, and for young Trey Milligan, that someone is Wendy.

To understand Frank Murtaugh, the man, is to know that he moves through his days with his very own Holy Trinity: family, baseball, KISS. And Murtaugh the novelist clearly had this trinity at his elbow as he wrote Trey’s Company. The warm nostalgia of family and a ballgame on the television are folded into every chapter; the ideals of Americana, just a neighboring porch away in Gran’s neighborhood.

Baseball is a constant with Trey — his team, as is his creator’s, is the St. Louis Cardinals — and he collects rookie cards and spends hours pitching a rubber ball to himself off the backyard deck (a baseball stadium of his own imagining). He and Libby visit Gran’s sister in her retirement home, the very idea a nightmare for some kids, but the Milligan siblings adore all contact with family, even when that family is a racist uncle who has a way with horses.

So there is Murtaugh’s trinity save for KISS. While the theatrical hard-rock quartet doesn’t make an appearance in the novel, the shadowy evil their shows portend does as the author rains hellfire (and actual fire) down upon his characters. The summer of 1982 is the axis upon which life turns, and it is through loss and fear and death that Murtaugh evokes the change of season for Trey, his Everyboy. Heaped upon a first kiss, a first date, and the milestone of glimpsing an older woman in bra and panties, there is the unknowable loss of someone close and a brush with tragedy and the law that shakes this 13-year-old to the core.

In the end, we wish Trey’s childhood could go on indefinitely, just as we wish all childhood might. If not an actual stunting of age, then the innocence that accompanies those magical years. A time when we might not know of death so close, of racist uncles, of fear and pedophiles and the heat from the fire of adulthood.

If that Peter Pan wish can’t come true, then we’ll wish to travel those rolling neighborhood streets with friends who will help see us through. “Choose the people you let in, Trey,” Geraldine, the ice cream lady and neighborhood sage, says. “Choose them very carefully. They’ll help you pave your path.”