The Memphis area exported about $1.4 billion worth of goods to its top three international markets — Mexico, China, and Canada — in 2023, according to the latest data, but effects of tariffs aren’t yet known.

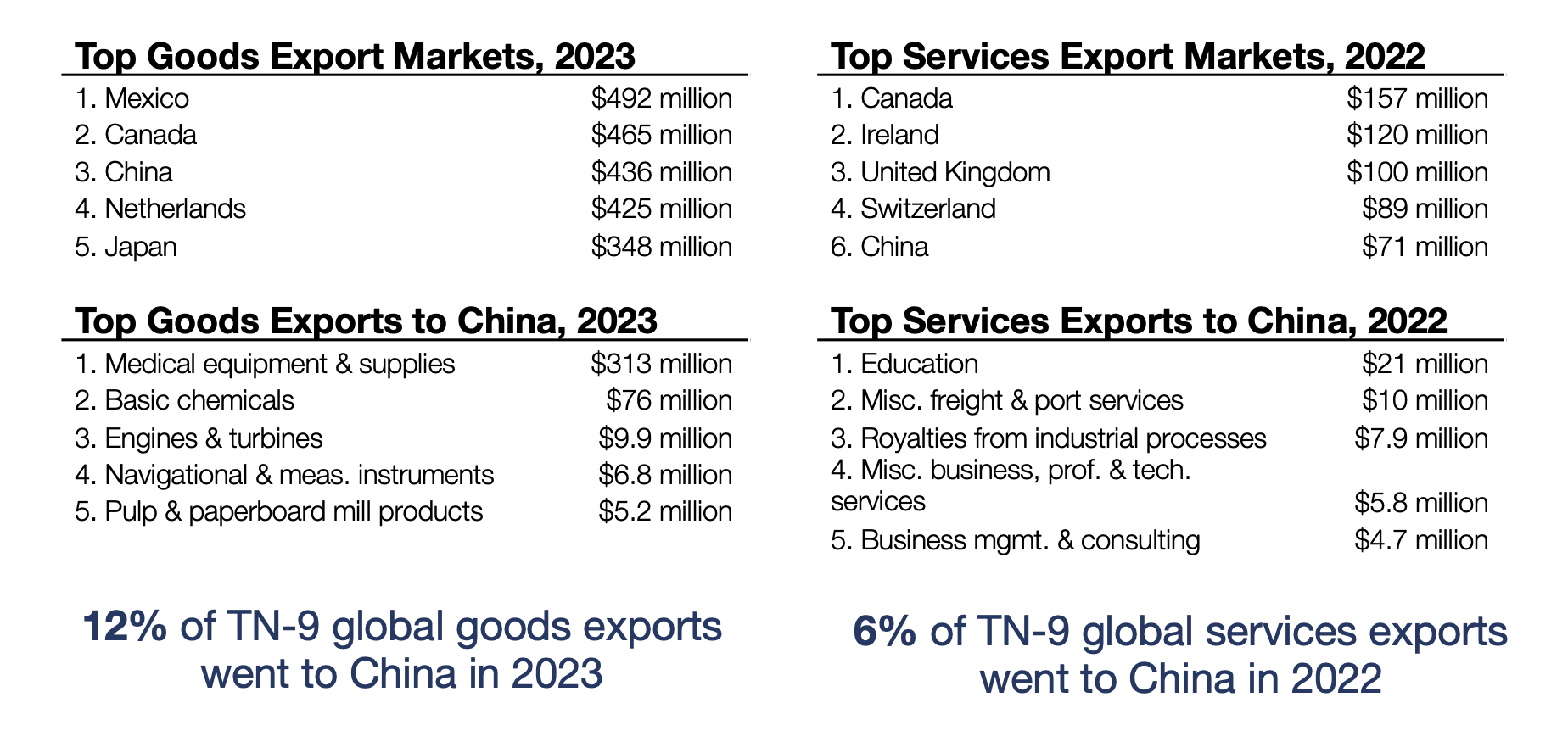

The report from the U.S.-China Business Council (UCBC) also found that Tennessee’s 9th Congressional District, which covers most of Memphis and parts of Tipton County, exported about $537 million worth of services to its top six international trading partners. Those include Canada at the top and China at sixth.

It’s unknown how those markets would change under promised tariffs by President Donald Trump. The president agreed to pause tariffs on Mexico Monday to allow the countries to work out a deal. Trump also agreed to lower the tariff price on Canada to 10 percent from a threatened 25 percent.

Stocks for FedEx Corp., one of the area’s largest private employers, fell by more than 6 percent on the New York Stock Exchange by Monday afternoon. Shares fell $16.29 to $248. 58 just before the closing bell.

However, the freight sector had already slowed before the the 2024 election. FedEx dropped the U.S. Mail as a customer last year, a move that cut 60 flights to Memphis International Airport.

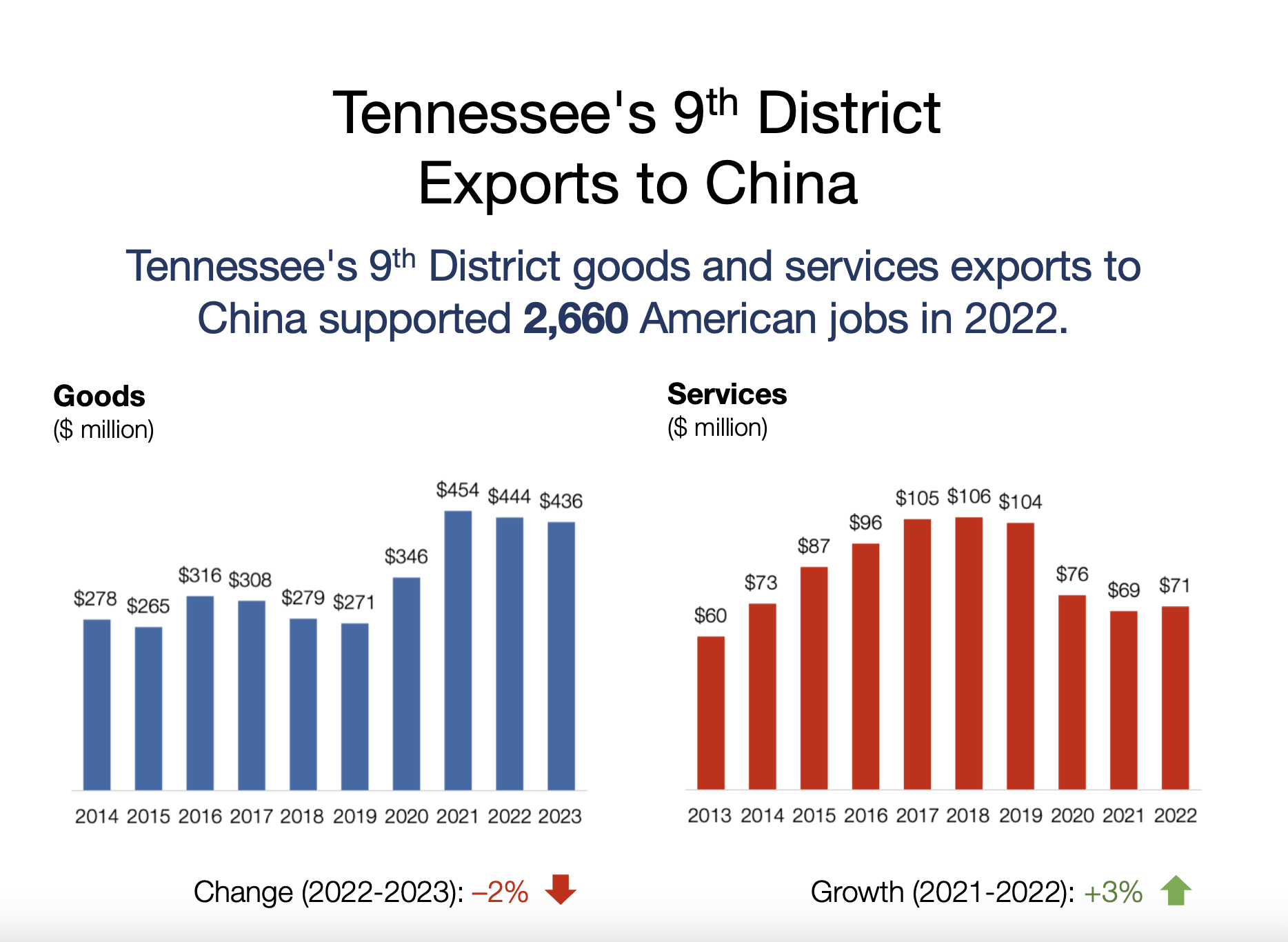

The UCBC report shows that the 9th District’s top exports to China alone were medical equipment and supplies ($313 million), basic chemicals ($76 million), and engines and turbines ($9.9 million). Changes to the China market alone could put downward pressure on Memphis companies like Medtronic, Drexel Chemical Co., and a host of mechanical companies.

The district also exported $38.9 million worth of services to China, also. The top three include education ($21 million), freight and port services ($10 million), and royalties from industrial processes ($7.9 million).

Market data was broken down to the district level in reports on trade between Tennessee and Mexico and Canada.

Total trade with Mexico in 2023 was $20.1 billion, according to the Embassy of Mexico in the U.S. The figure includes $6.1 billion in exports and $14 billion in imports. The state’s biggest import categories include motor vehicles, motor vehicle parts, HVAC equipment, electrical equipment and components, and communications equipment. In all, Tennessee’s trade with Mexico is greater than the total U.S. trade with Argentina, the embassy report says.

The latest report from the Canadian Consulate General in Atlanta says that trade with Canada supported 160,400 employees in Tennessee last year in addition to the 11,700 employees at Canadian-owned businesses across the state.

Tennessee exports $10.0 billion in goods and services to Canada. The state imports $6.8 billion in goods each year, the report said. Those include chemical, metals, and equipment — base goods that, with tariffs added to their costs — could drive up prices on a number of products for Tennessee consumers.

Also, Canadian-based company Richardson International Ltd. announced last year it will invest $220 million in its Wesson Oil production facility in Memphis. That is part of a multiphase project that will replace the oil production plant with a new refinery to fulfill customer requirements and meet growing global demand for vegetable oil. The company said when it is completed, the new refinery will drive substantial reductions in water, energy, and wastewater volumes.

In West Tennessee, auto parts maker Magna International plans to invest more than $790 million to build the first two supplier facilities at Ford’s BlueOval City supplier park in Stanton.

Magna’s two Stanton facilities include a new frame and battery enclosures facility and a seating facility. The company also plans to build a stamping and assembly facility in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.

The Ontario-based supplier will supply Ford’s BlueOval City with battery enclosures, truck frames and seats for the automaker’s second-generation electric truck.

Magna will employ approximately 750 employees at its battery enclosures facility and 300 employees at its new seating plant. The company plans to employ about 250 employees at its plant in Lawrenceberg. Production at all three plants is scheduled to begin in 2025.