Maya Smith

Maya Smith

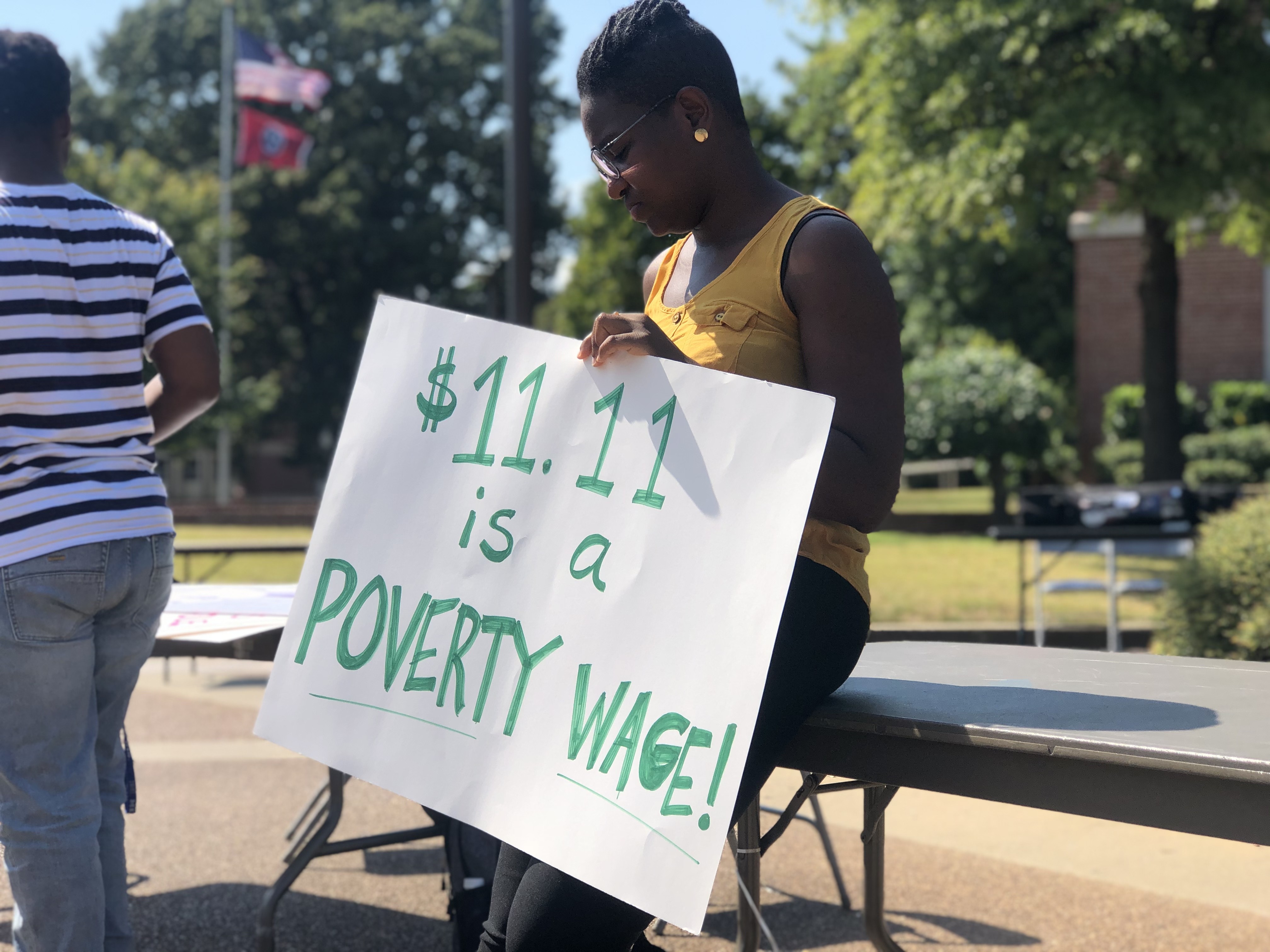

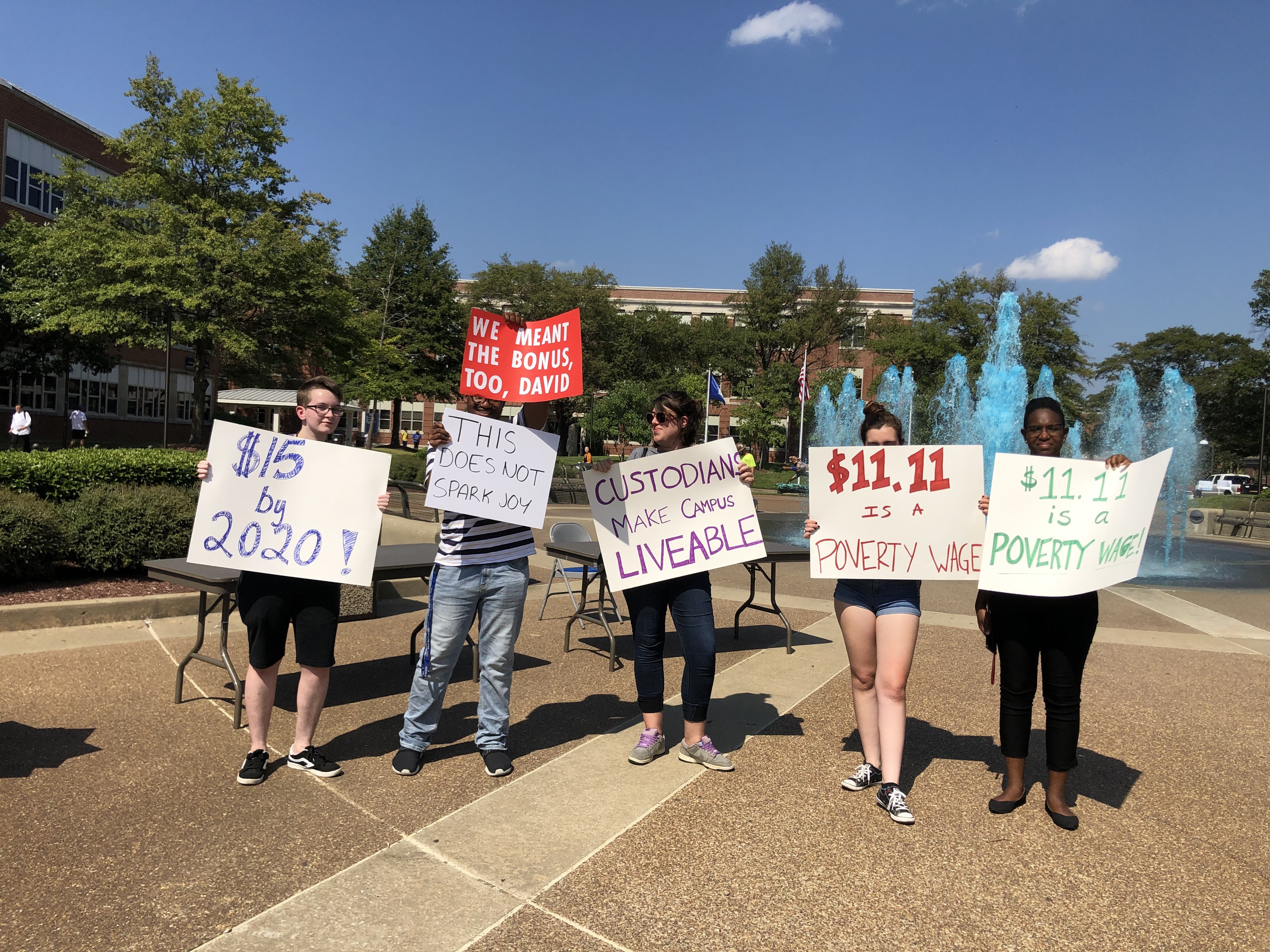

Students demand living wage for all campus workers at a fall protest.

University of Memphis president M. David Rudd announced Monday that the university has a plan to increase the minimum wage for campus employees to $13.

In an email sent to the university’s staff and faculty, Rudd laid out a two-part plan to increase the minimum wage of all regular hourly employees to $13 an hour by July.

“Since I started my tenure as present, our leadership team has made a firm commitment to raise the wages of our lowest-paid employees,” Rudd said in the email. “As I have mentioned on many occasions, we are doing so in a financially responsible and sustainable manner. We have an equally firm commitment to also keep the cost of education low for our students.”

[pullquote-1]

In 2018, the university increased minimum wage from $10.10 to $10.60 an hour, and then in 2019, those wages were increased again to $11.11.

Now, the plan is to increase the minimum wage to $12 in April and then to $13 by July 2020.

Rudd first promised a plan to raise the minimum wage of campus employees in July after Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris vetoed a Shelby County Commission decision to allocate $1 million for the U of M’s Michael Rose Natatorium because of the school’s failure to pay living wages to some employees.

The commission voted to override the veto, but the public debate prompted Rudd to publicly declare his commitment to a definitive plan to raise the campus minimum wage to $15 over the next two years.

Monday’s announcement is the first step the campus has seen toward that plan.

The Tennessee State Employees Association (TSEA) applauded Rudd’s Monday announcement: “TSEA appreciates President Rudd for keeping his commitment to increasing wages of University of Memphis’ Higher Education state employees.”

But members of the United Campus Workers (UCW) were surprised by Rudd’s announcement, said Jayanni Webster, West Tennessee organizer for UCW.

Webster said she spent the morning discussing Rudd’s plan with UCW members who have been pushing for $15 an hour since 2014.

These workers maintain that $13 isn’t sufficient and that their goal remains $15 an hour, she said. “We are not done with this issue, not one bit,” said Doris Brooks-Conley, a U of M custodial worker of 19 years said.

[pullquote-3]

Another campus custodian, Sharon Gale, who has worked at the U of M for five years, said she and co-workers have been asking for better pay “for a long time. It’s been really hard for me trying to keep up with bills and expenses. At the end of the day, we need the $15. Hopefully Dr. Rudd keeps his promise and we see it by the end of the year.”

UCW members are also concerned about whether or not these raises will affect employees receiving merit or cost-of-living raises this year.

Shelby County Commissioner Tami Sawyer, the lone commissioner who voted to uphold Harris’ veto this summer, said the wage increase announced Monday is the “first step toward $15, which we hope to see not too far from this increase.” Sawyer adds that she is proud to have stood with Mayor Harris on this issue and that she will “continue to advocate until poverty wages are eliminated.”

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips