Hopper Seely is a perfect name for a brewery owner.

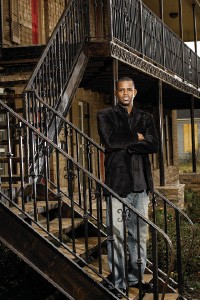

Seely, 27, is owner of Grind City Brewing Company, but “Hopper” has nothing to do with “hops,” which are flowers used to make beer.

“People think I made the name up when I started the brewing company,” Seely says. “I wish I did. That’d be more clever. My parents named me Hopper.”

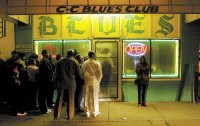

Since opening the brewery in 2020, Seely now distributes beer in three different states. The brewery holds public events in the tap room, where they keep 12 to 17 beers on tap. “We always keep it rotating with new, fun stuff. In markets, as of now, we have three products: Godhopper IPA, Tiger Tail craft malt liquor, and Poppy’s Pils pilsner.”

Their beer is in Kroger and other “major grocery chains that are known for selling craft beer, independent liquor stores, and bars and restaurants.”

In late March, Grind City beer will be in new cans. It’s part of the company’s rebranding to keep the business fresh.

Grind City uses “TCB” as its public slogan. But, unlike Elvis, theirs stands for “Taking Care of Beerness.” They also use “TCB” for the company’s pillars, Seely says.

The “T” stands for “Traditional”: “We’re a traditional American craft brewery.” The “C” stands for “Communal”: “We want to be a part of the community,” he says, adding, “We routinely partner with charities, and we all are part of developing Uptown in general, making sure the neighborhood gets cleaned up.” And the “B” stands for “Betterment”: They are working to “make sure Uptown gets redeveloped. Since we started the brewery, there have been two businesses that started because of what we did.”

Building Up Uptown

The brewery is on the border of the Greenline. Construction has started on the bike path, which will connect Downtown and North Memphis all the way through to Shelby Farms.

Uptown businesses have been growing since Grind City opened, Seely says. “Of all things, a brewery [Soul & Spirits Brewery] started after we started here. We’re seeing developers really following through. There’s construction being built up all over Uptown. There are apartments and a multi-use blend of retail and living spaces.

“I would say it has the feeling of a neighborhood in Downtown. South Main is awesome, but all the apartments are right next to each other. But if you want a slower paced, more relaxed, really family-centered part of town, that is what Uptown is now. And that’s what it’s being developed into.

“I think eventually somebody was going to start the first retail business in Uptown. We just happened to be the first one to do it.”

When trying to decide where to open a brewery, Seely thought, “Do we get a property in the heart of Downtown or do we go Midtown?

“Then I had to sit back and think, ‘What do breweries do the most?’ They build communities. Broad Avenue wasn’t what Broad Avenue is today without Wiseacre [Brewing Company] planting their flag on Broad.”

Same thing happened to areas around Ghost River Brewery & Taproom at Crump and South Main, Memphis Made Brewing Co. in Midtown, High Cotton Brewing Company in The Edge, and Meddlesome Brewing Company in Cordova, Seely says.

Seely looked at Pinch and Midtown but wanted to be “part of an area that can use development.”

In 2017, he discovered a LoopNet photo of North Second Street in Uptown. It was just one overhead shot. But he learned the 4.65 acres at 76 Waterworks Avenue included 40,000 square feet of warehouse space. “It was right across from Harbor Town, a stone’s throw from St. Jude. I said, ‘I’ve got to check this place out.’’’ Then, he says, “I saw the view.” It showed “the entire Memphis skyline perfectly.”

Seely bought the location, which had been the old Tri-State Veneer & Plywood. “They were a custom bent wood chair factory. If you bought a wooden chair before 2000 in America, there was a really good chance you got it at Tri-State.” The company had molds to make “every part of a chair imaginable, and you could customize it.”

The property included four 10,000-square-foot warehouses. “One building was salvageable, and that’s the building we occupy.”

Born to Beer

His middle name notwithstanding, Seely’s life has basically involved beer in one way or another.

Born in Memphis, his full name is William Hopping Seely V. “They said, ‘We’ll call you Hopper,’ because every version of William — mostly Bills — has already been used.”

His mom, a movie fan, liked actor Dennis Hopper, and his dad thought Hopper sounded like a good athlete’s name. “Chipper Jones was kind of in the spotlight at that time.”

But, Seely says, “I sucked at baseball. That didn’t work out. I actually did wrestling. I did every sport, but I stuck to lacrosse and football.”

When he was 13, Seely began home-brewing beer with his dad. “He wanted to have a father-son bonding experiment on the weekends he’d be home. And he needed to pick something that a punk middle schooler would be willing to stay home on a Saturday and do with his dad.”

There was one condition: “I was not allowed to sample the beers that we would make.” But, Seely admits, “I’m not saying a sample wasn’t taken when no one was around.”

His mother served his home brews, including his amber lager, at Thanksgiving dinners. And they were a hit. “That brought me so much joy as a middle schooler all the way through high school.” He realized what he enjoyed the most about beer was other people’s reaction to it.

Seely, who went to Briarcrest Christian School, remembers when his teacher asked freshman class members what they wanted to do for a living. “I said, ‘I want to start a brewery.’ That didn’t go down so well.” But he was being honest when he said he liked the “science and math of it” rather than the taste.

Seely’s first beer was a taste of Guinness Extra Stout. “My grandmother loves German beers and Guinness. And she really loves European-style beer. I was like, ‘Oh, can I try it?’ And she thought she’d be able to pull the old ‘I’m going to let you take a sip and you’re going to hate it and we’re good for life.’” That didn’t happen. “I liked the chocolaty-ness of it.”

As he got older, Guinness Draught was Seely’s go-to beer. “People would tailgate with Bud Light and I would tailgate with Guinness Draught. Those are still notes I appreciate in beer today.”

Seely attended Boise State University, but when he was 18 he enrolled in a nine-week course at Brewlab, a brewing school in Sunderland, England. “I learned I know nothing about beer.”

Many fellow students dropped out, but Seely told himself, “If you quit this, you’ll quit everything else for the rest of your life.” He thought, “I have to get through this. … And I did. I ended up graduating third in my class.”

Building a Business

Seely’s goal was “to work at as many breweries in the Mid-South as possible,” and he worked for two years at Yalobusha Brewing Company in Water Valley, Mississippi, and another two years at Ghost River Brewing Co.

He then began formulating a business plan for his own brewery. “I wanted Grind City Brewing to be the pub of Memphis.”

“Pub is short for ‘public gathering,’” Seely says. “I want to be part of your good times. I want our beer to be the one you select to have with your friends.”

Seely still loved Guinness and heavy IPAs, but, he says, “After Brewlab, I had a whole new respect for light beer. It is the hardest beer to make. If you think of light beer as tap water, you know bad tap water when you taste it. It doesn’t seem like a big deal, but the tiniest mistake in a light beer is highlighted. Just because the whole point of a light beer is for it to be similar to water. Super subtle flavors.” It can be bitter, buttery, or slightly tart “if you don’t have the proper brewing process.”

Seely came up with a light beer that is “super light, super drinkable. But there’s a subtle flavor that you get from our yeast.” He added subtle fruit and spice flavors. “And that’s just from experimenting with dozens of different yeast strains to figure out the one subtle note we wanted.”

Tony Allen, a Memphis Grizzlies player at the time, was the inspiration for the name, which was his wife’s idea. “Tony Allen said something along the lines of, ‘That’s what we do. We grit. We grind. We are Grind City.’”

Seely bought the old chair factory in 2018, but spent about two and a half years renovating it. A lot of chair parts, mostly chair backs and furniture molds, were left behind. “We wanted their history to be a part of our history. We took the molds they left there and we created almost all of the tap room core. The furniture, the fixtures, that wall are all made from actual molds and furniture pieces.” His uncle and mother built the tables using Seely’s concept of repurposing molds as table tops and wood pieces for the legs.

Blueprints for the Future

On May 11, 2020, Grind City Brewing Company had its “first sale for liquor stores and grocery stores,” Seely says. The Godhopper IPA, Viva Las Lager, and Soulbier black lager were their first three beers.

Cordelia’s Market was one of the first places to sell their beer. “Grind City Brewing is a personal favorite of mine, from their crushable [easily-drinkable] year-rounds to their mouthwatering sours,” says the store’s beer and wine buyer Morgan Pirani. “I know I can always trust the guys in the brew house to create a masterpiece for the masses.”

Grind City began to grow, but, Seely says, “The money we had budgeted for marketing, we had to use to keep us afloat because we couldn’t open our tap room and we couldn’t sell beer to everyone we wanted to during the pandemic.”

They finally opened the tap room that October. “That’s when we realized this is going to work. Just the support from the city. We had a huge day. Everybody came out.” And, he adds, “People were loving the beer.”

Blueprints from the old chair factory are the design on the new cans. “We saved them all and that’s actually the background art on the new cans.”

“We really wanted to focus on who we are and try to express that in a can,” says Grind City director of events Ian Betti. “And that is difficult ’cause the brand as a whole is built around this feeling of community and craftsmanship and, essentially, betterment.”

Their “main job” as a company is “to improve on what is already happening in Memphis,” he adds. The blueprints on the cans are “a nice nod to the past that helps us build the future. Internally, we’re calling it ‘a blueprint to your good times.’”

Grind City also is adding new beers, including Belga, a Belgian-style wheat ale, Seely says. And they’re adding Thaddeus, an amber lager. “We named it Thaddeus because of St. Jude Thaddeus.” The beers previously were only available in the tap room, Betti says.

But, Seely says, “Nothing is finished. Everything has just begun.” They want to do more with their yard. “We did a music festival last summer, and it was a big success.”

They currently do “awesome music sets,” featuring “fun, laid-back music” inside and outside, Seely says.

One of his goals is to have a permanent stage. Another is for the Dave Matthews Band to play at the brewery.

But Seely has a main goal for Grind City Brewing Company: “I want to be able to bring my kids to the brewery. And when they’re old enough to understand where they are, I want to be able to tell them, ‘This is not what Uptown looked like before we started.’”

Google Maps

Google Maps  Google Maps

Google Maps  Google Maps

Google Maps  ioby

ioby  Wolf River Conservancy

Wolf River Conservancy

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks