Winter is here, and there’s no way to escape it. Unless you consider the arts an escape. In that case, you’re in luck, since Memphis has no shortage of arts events this season, and as always, our local arts organizations are still tilling the soil for us to reap the benefits. In fact, this winter, a few of our favorite organizations are celebrating major milestones — 10, 25, and 60 years (read about them below). Be sure to mark your calendars for what’s to come — an extensive list of winter arts events can be found at the end of this feature or by visiting memphisflyer.com/calendars.

Carpenter Art Garden

The Purple House on Carpenter was once a site of unseemly activity — “if you know what I mean,” says Megan Banaszek. Now, the house, which was rebuilt from the foundation, is home to Carpenter Art Garden (CAG), for which Banaszek serves as executive director. It’s still purple, but today its porch holds a communal bookshelf, bulletin boards of community activities, and a table of free bread and hats. Inside you can find art and music lessons for kids, community meetings, and a laundry co-op. “It’s funny,” says Banaszek. “People are like, ‘The Purple House does what now?’”

With the intention to make up for a lack of art programming in Binghampton, the nonprofit started in 2012 in the empty lot next door, now dubbed the Art Garden. “The idea for this space was to be an outdoor art classroom,” Banaszek says, “so people cleared it out, put down a shipping container [for storage], put down some picnic tables, and just met here on Tuesday afternoons to lead different art classes.

“There were a lot of opportunities for firsts in terms of having access to these programs. For any age student, just having something that you get to sit, focus on, hands-on is a way to unwind, connect with people you’re familiar with after school, and be expressive.”

Those Tuesday drop-in art classes continue today, but by 2014, CAG wanted to do more. So it bought the Purple House and started offering small-group classes throughout the week. Classes range from violin with Iris Orchestra to ceramics with staff and guest artists. “And if someone says, ‘I wanna learn about screen printing,’ we’ll try and track someone down and do a class,” Banaszek says. They’ve even added opportunities for teen employment.

Now there’s also the Carpenter Street Workshop, where kids can learn bike mechanics, sewing, and cooking; Aunt Lou’s House, where tutoring is offered; two community gardens, where staff tend to seasonal crops that are sold at the twice-weekly pop-up market; and the Mosaic Garden, where community members can sit and enjoy CAG’s various mosaic creations, which were designed and executed by the student-run Mural Arts Apprentice Team.

“Any time something gets added, I kind of can’t believe it,” Banaszek says, “but I think it’s at a good spot right now.”

This week, through December 8th, CAG is hosting its annual Holiday Bazaar, where patrons can purchase student work, with 70 percent of the sales going to the student and the rest into CAG programming. Popular items include Griz Hearts ornaments, pot holders, Christmas cards and gift tags, and bead hangings. As a bonus with each purchase, Banaszek says, “The kids get a sense of pride when they are able to sell.” You can also purchase work online at carpenterartgarden.org/shop.

UrbanArt Commission

For UrbanArt Commission (UAC), the canvas stretches from one end of the city to the other, with endless opportunities for public art. So far, the organization, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, has filled that canvas with 130 projects — from sculptures in Binghampton to murals at Central Station Hotel. Yet, even with such a widespread footprint, Lauren Kennedy, UAC’s director, never worries about running out of space.

“I can drive around town, dream up like 15 projects, just going to Kroger and back,” she says. “There are so many great ideas that we haven’t gotten to tap.”

Since 1997, UAC has worked with the city, neighborhood groups, and municipal authorities to produce meaningful public art, from murals to sculptures. “Public art, when you boil it down, is about making an investment in a shared space,” Kennedy says. “When public art is doing what it should do, it is also reflecting the people and experiences in that community. It’s a real boon for neighborhood pride.”

For Kennedy, the project she takes most pride in is the Concourse B installation, completed this year. For it, UAC, in partnership with Memphis International Airport, selected more than 40 works of contemporary art for the airport with a goal to highlight Memphis’ vibrant and eclectic range of artists and to reflect the city as a whole — not just Elvis, blues, and barbecue, but everything in between that gives the 901 its texture.

Of course, the Concourse B installation wasn’t the only project that came to fruition recently. After a pandemic-induced delay, the nonprofit kicked off its New Public Artists Fellowship in 2021, wrapped up the first cohort’s experience this summer, and will accept another six artists in the spring. The fellowship provides in-depth training and professional development for artists wanting to break into public sculpture, and it’s capped off with a temporary public installation. Fellowships like this and the District Mural Program, which Kennedy describes as “the same concept but focused on murals,” allow UAC to leverage their funding to prepare local artists for more opportunities down the road, in and out of Memphis.

“Large-scale public art is not something that is particularly easy to dive into,” Kennedy says. “It’s one thing to have your work in a gallery or a museum, but to paint the side of a building that thousands of cars are driving past on a regular basis is really huge.”

After all, public art lasts lifetimes, and UAC cares that the community continues to enjoy the projects long after their completion. “In the past five years, in particular,” Kennedy says, “we’ve put more emphasis into thinking about how people continue to interact with these things over time.”

This year, after a pandemic pause, UAC brought back its bi-monthly Artist Happy Hour Series, where artists can network, and its Revisiting Series, which are temporary site-specific responses to existing public art projects. The nonprofit also offered yoga by current projects twice this year, and Kennedy assures, there’s more public programming to come in 2023.

ArtsMemphis

Founded in 1963 as the Memphis Arts Council to help fund various local arts organizations, ArtsMemphis has navigated all the ups and downs that have come within those 60 years. But Elizabeth Rouse, the organization’s president, says, the effects of the pandemic on the arts in Memphis was like nothing they’ve seen before.

“We saw how overnight so many were out of work,” she says. “It was certainly hard on artists and arts administrators.” Pre-pandemic, nonprofit arts in Memphis had a $200 million economic impact and boasted more than 6,000 full-time positions.

With so much at stake, though, both the general public and the arts community had a reinforced appreciation for all that the arts can offer, and from that, opportunities for change and growth arose.

“Like many funders, we, over the pandemic, have been much more connected with our grantees,” Rouse says, “and it’s really helped to foster a sense of community as everyone in the art sector navigates new times. The pandemic also forced organizations to be a bit more flexible and think differently about how they deliver programs.”

For ArtsMemphis, one of the biggest changes was being able to support a larger number of individual artists than ever before. About 10 years ago, the nonprofit had started to “tiptoe” into the arena with a few yearly grants, but the pandemic spurred the Artist Emergency Fund, which has since shifted into the Recovery Fund, both in partnership with Music Export Memphis. As of last month, through this fund, they have given out $1 million to artists of all disciplines, but particularly music.

Last year, the organization gave out $3.1 million to 68 organizations and hundreds of individual artists. “Those organizations are doing work in every zip code in Shelby County,” Rouse says. “It’s really about using the arts as a community resource and to bridge differences and offer these points of healing and connection and so much more.” And that includes economic impact. “We’re in the midst right now of doing a new economic impact study, and we’re excited to see how those numbers have hopefully grown.”

Part of this success, Rouse attributes to the intentional collaboration among the arts community. “It’s what makes Memphis unique,” she says. “And I think that’s represented during ArtsWeek.”

For ArtsWeek, which began on December 3rd and ends December 11th, various organizations are hosting events throughout the city. “In 2020, when things were actually shut down,” Rouse says, “Mayor Harris and Mayor Strickland designated a week to celebrate, support, and build awareness for our local arts sector. Our hope is that people will experience something new in the arts.”

And this ArtsWeek also happens to be the kick-off for ArtsMemphis’ 60th anniversary. “There’s an exciting future ahead, especially as we continue to expand our support for both organizations and artists and as people engage with the arts in new ways and the arts become much more accessible.”

Find out more about ArtsWeek and year-round events at artsmemphis.org.

WINTER ARTS GUIDE

ON DISPLAY

once a river, once a sea

Maysey Craddock’s paintings, examining growth and decay along the Gulf Coast.

David Lusk Gallery, through Dec. 23

Les Paul Thru the Lens

Gallery of photos highlighting the life of Les Paul.

Stax Museum of American Soul Music, through Dec. 30

Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet

Author Maurice Sendak’s illustrations, dioramas, and costumes.

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, through Jan. 8

Simple Pleasures: The Art of Doris Lee

Exhibition of one of the most popular figurative American artists.

Dixon Gallery & Gardens, through Jan. 15

Master Metalsmith: Lynda Watson | Looking Back

Watson’s visual diary, incorporating metal, felt, charcoal, and found objects.

Metal Museum, through Jan. 29

Watercolors by Jacqueline Foshee

Charming landscapes and street scenes.

Memphis Botanic Garden, through Feb. 5

Those Who Hold Dominion Here

Serpentine sculptures by Sarah Elizabeth Cornejo.

Crosstown Arts Galleries, through March 5

Mending in a State of Abundance

Katrina Perdue’s damaged objects, repaired with colorful threads.

Crosstown Arts Galleries, through March 5

Summer in Shanghai

Three-part video series by Janaye Brown.

Crosstown Arts Galleries, through March 5

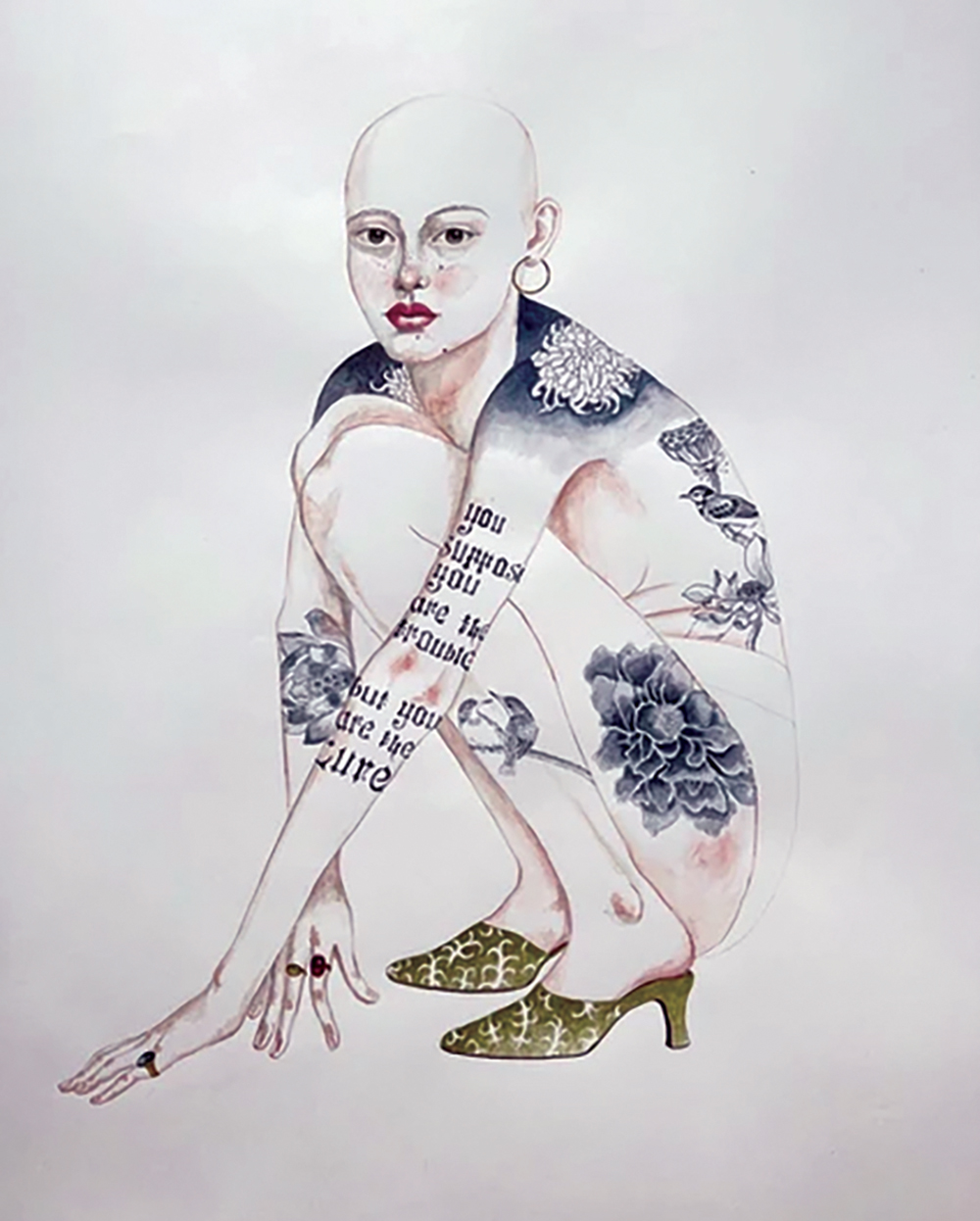

Anne Siems

Paintings of fantastic, almost supernatural women.

David Lusk Gallery, Jan. 3-Feb. 11

Sharon Havelka

Mixed media quilt sculptures from found objects.

Beverly & Sam Ross Gallery, Jan. 14-Feb. 25

Shared Spaces

Works by Rob Gonzo and the late George Hunt.

Buckman Arts Center, Jan. 20-March 6

2023 Mid-South Scholastic Art Awards

More than 135 artworks by area youth.

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Jan. 20-Feb. 19

Artificial Intelligence: Your Mind & The Machine

Exhibit highlighting artificial intelligence and its relevance to STEAM.

Museum of Science & History, Jan. 22-May 6

Tennessee Triennial

A major statewide contemporary art event organized by Tri-Star Arts and including the Brooks, Memphis River Parks Partnership, TONE Memphis, and UrbanArt Commission.

Various locations, Jan. 27-May 7

Tommy Kha: Eye Is Another

Site-specific, photography-based installation by Tommy Kha.

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Jan. 27-May 27

American Made: American Art from the Jacobsen Collection

Surveying two centuries of American creativity.

Dixon Gallery & Gardens, Jan. 29-Apr. 16

Dereje Demissie

Ethiopian artist reflects on the geography and culture of his homeland.

Urevbu Contemporary, Feb. 1-28

ON STAGE

Navidad Spectacular!

Cazateatro Bilingual Theatre Group’s Christmas musical with Latin flavor.

Evergreen Theatre, through Dec. 11

I Dwell in Possibility: Emily Dickinson Emerges

A one-woman play with the reclusive poet.

Tennessee Shakespeare Company, through Dec. 11

Velveteen Rabbit: The Musical

The beloved tale of the Velveteen Rabbit.

Hattiloo Theatre, through Dec. 18

Who’s Holiday

Cindy Lou Who spills the tea on all that’s happened since you last saw her.

The Circuit Playhouse, through Dec. 22

Junie B.’s Essential Survival Guide

Your favorite first-grader Junie B. is back.

The Circuit Playhouse, through Dec. 22

The Wizard of Oz

Experience the magical land of Oz.

Playhouse on the Square, through Dec. 22

A Christmas Carol

Ebenezer Scrooge faces his past, present, and future.

Theatre Memphis, through Dec. 23

It’s A Wonderful Life

Radio-play adaptation of the Christmas classic.

Bartlett Performing Arts & Conference Center, Dec. 9-11

Magic of Memphis!

Memphis performing groups celebrate the holiday season.

Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, Dec. 10

Nutcracker

Ballet Memphis’ take on the Christmas classic.

Orpheum Theatre, Dec. 16-18

Handel’s Messiah

Presented by Memphis Symphony Orchestra (MSO).

Various locations, Dec. 20-23

Mannheim Steamroller Christmas

Christmas classics in the distinctive Mannheim sound.

Orpheum Theatre, Dec. 29

If Pekin Is a Duck, Why Am I in Chicago?

A lyricist and a composer try to write while kidnapped.

TheatreWorks, Jan. 13-29

Sondheim Tribute

Celebrating Stephen Sondheim’s body of work.

Theatre Memphis, Jan. 13-29

The Long Goodbye: A Rock Opera

An experimental rock opera about loss, change, and self-reflection.

Evergreen Theatre, Jan. 13-15

Escaped Alone

Four older women meet for tea and ruminations on catastrophe.

TheatreSouth, Jan. 20-Feb. 5

Scottsboro Boys

A retelling of the landmark trial of nine falsely accused Black teenagers.

Playhouse on the Square, Jan. 20-Feb. 19

Mendelssohn Violin Concerto

Schumann’s symphonic journey down the Rhine River, as presented by MSO.

Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, Jan. 21-22

Tosca

Opera Memphis presents Puccini’s masterpiece.

Germantown Performing Arts Center, Jan. 27-28

Cyrano de Bergerac

Edmond Rostand’s exquisite 1898 tale of secret love.

Tennessee Shakespeare Company, Feb. 2-19

Cirque Zuma Zuma

The ultimate circus set to the hot, rhythmic pulses of Afro-jazz.

Buckman Arts Center, Feb. 3

Macbeth

Shakespeare’s famous tragedy.

Theatre Memphis, Feb. 3-19

Rise

Collage Dance Collective’s ballet set to Dr. Martin Luther King’s final public speech.

Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, Feb. 3-5

Roe

The divergent stories of Roe v. Wade’s plaintiff and her lawyer.

The Circuit Playhouse, Feb. 3-19

Shakin’ The Mess Outta Misery

A timeless coming-of-age story, set in the 1960s South.

Hattiloo Theatre, Feb 3-26

The 10 Hilarious Commandments

Presented by Memphian Demario “Comedian Poundcake” Hollowell.

Halloran Centre, Feb. 4

Misery

The story of a romance novelist who ends up trapped in his fan’s secluded home.

TheatreWorks, Feb. 10-23

Pilobolus

Radically creative and boundary-pushing dance.

Germantown Performing Arts Center, Feb. 11

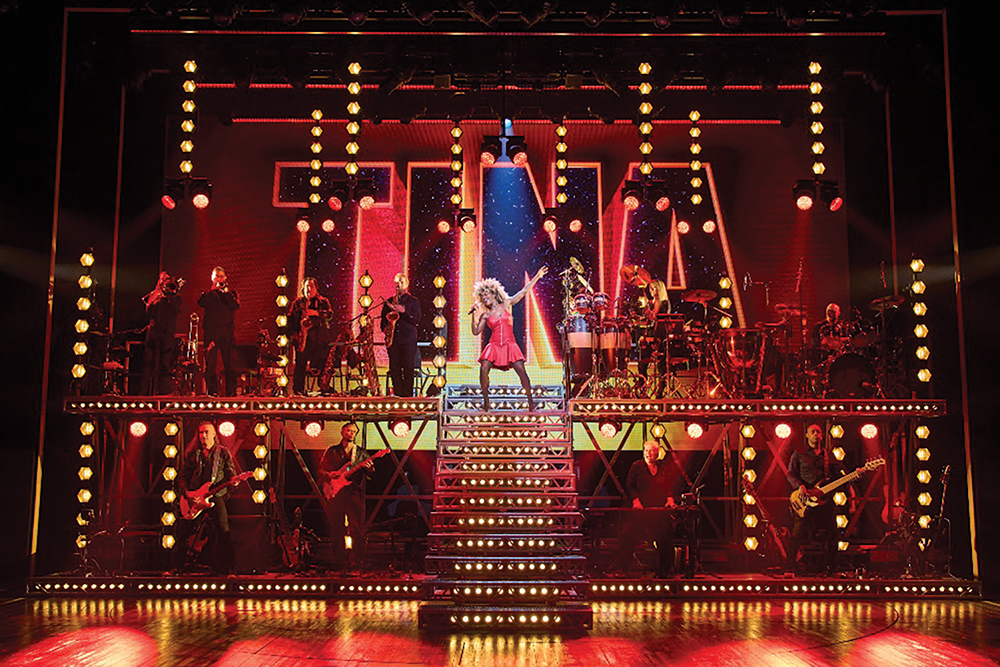

TINA: The Tina Turner Musical

Tina Turner’s story as written by Memphis-born and Pulitzer Prize-winning Katori Hall.

Orpheum Theatre, Feb. 14-19

Star-Crossed Love: Romeo and Juliet

MSO presents the celebrated ballet score of Shakespeare’s famous work.

Various locations, Feb. 18-19

ART MARKETS

WE Holiday Market

Woman’s Exchange of Memphis, through Dec. 22

Holiday Bazaar

Arrow Creative, through Dec. 23

Memphis Arts Collective Holiday Artist Market

Poplar Plaza, through Dec. 24

WinterArts Market

Park Place Centre, through Dec. 31

Facebook- Paint Memphis

Facebook- Paint Memphis  Paint Memphis

Paint Memphis  Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens

Colin Kidder

Colin Kidder