In covering the Memphis music beat, I talk to a lot of inspired artists — composers, singers, and performers who have rattled the world with their choice of notes, their tone. And they’ve worked in a variety of genres as sprawling as the city itself. But through all the conversations, all the life stories that come pouring out of them, there’s a common thread: church music.

Herman Green, recalling the days of his youth in the 1930s, before he’d ever imagined mastering the saxophone: “I played guitar with a blind pianist man named Lindell Woodson, who played piano for my stepfather’s church. I don’t even know how he could tell what key it was, but he’d get all over that piano like Art Tatum. And it was the Church of God, [claps and sings], you know? It was that kind of thing.”

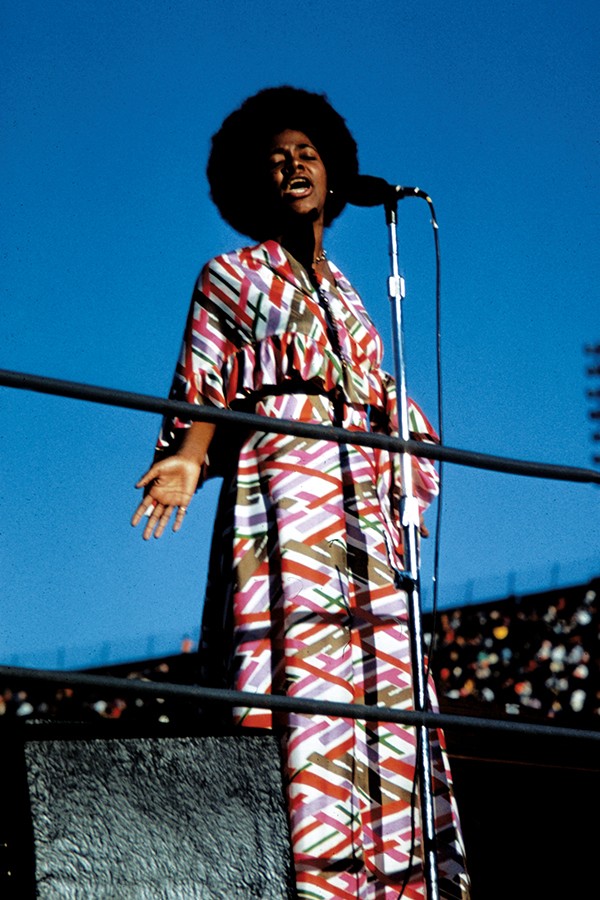

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Fellowship Baptist Church

Booker T. Jones, on his earliest years as a musician: “I want you to mention Merle Glover. She was the organist, and she played the pipe organ. That was the first organ I ever played, at Mt. Olive Cathedral, over by Porter School on Vance Avenue. I was the pianist for the men’s Bible class. I was there at 9 o’clock every Sunday morning for years.”

William Bell, reminiscing about “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” his first hit for Stax Records: “At that particular time, I had been singing secular music in clubs, but the training and the background was strictly gospel. Most soul singers and country singers, we all came out of church … You sang with the choir for a while, and those choir rehearsals taught you how to sing in tune and treat a lyric and express an idea. So all of that helped as we created a career.”

DJ Squeeky, producer of 8Ball & MJG and Young Dolph, recalls growing up playing drums at First Baptist Church on Beale Street, where his mother has always gone. His uncle was “cold” — a master of any instrument in the church, able to jump in and accompany any singer, on any song.

MonoNeon

MonoNeon, trailblazing funk and avant garde bassist: “Eventually I started playing in church. That’s where I really got most of my skill from. Olivet Fellowship Baptist Church on Knight Arnold.”

Vaneese Thomas, noting how she and siblings Carla and Marvell grew up a little differently from most: “Our church was not the gospel experience people expect from Memphis. We grew up in a very straight-laced Baptist church. So we sang hymns and anthems.”

And that’s just a small sampling. Everywhere you turn, the influence of African-American churches on the Memphis sound — even in the era of hip-hop — is inescapable. The church crops up in nearly every musician’s biography, yet remains under-recognized for what it is: a crucible for musical talent and skill without parallel.

Minus Red Productions/Candied Yam Music

Minus Red Productions/Candied Yam Music

Kirk Whalum

In order to dig a little deeper into this milieu, I could think of no better guide than Kirk Whalum, composer, producer, and sideman extraordinaire, whose command of the saxophone has carried the tones and phrasing honed in his father’s church across the world.

“It’s that thing that we take for granted many times, but other people go, ‘Well, that’s just exactly what I need,'” Whalum reflects. “Whether it’s Quincy Jones — as many sessions as I’ve done with him — or many other artists, they hear Memphis in my sound. Not just Memphis, but Memphis church. And it’s specifically the black church. I mean, Aretha Franklin — her dad was pastoring a black church here. And, you know, Maurice White and David Porter were singing in a black church group in their formative years. So those are the things I’m talking about when I say it’s all about that soul that you get from that place. And that makes its way into art.”

If Whalum takes a philosophical perspective on the idea, perhaps it’s a family thing, given that his late father, Kenneth Whalum Sr., once was pastor of the Olivet Baptist Church on Southern Avenue, and his brother, Kenneth Jr., now presides over that church’s latest incarnation, the New Olivet Baptist Church. It’s only natural that Kirk looks beyond the more superficial influence of, say, the gospel repertoire.

“I think it’s more of an approach. In white culture — what represents Western white culture? I think ballet. In ballet, the more intense you get, the higher you get: literally, physically higher. And the pinnacle of ballet is en pointe. You’re on your toes, you know, and you’re reaching for the sky. And just the opposite applies to African music. When you hear people talking about getting down, it’s like the pinnacle of the African musical experience: You’re almost on the floor. You’re bending down all the way.

“I think that’s a good metaphor for the approach that you get from black music. It’s not about someone ‘playing soulful,’ it’s about believing in something and being a part of something and someone. In this case, Jesus. That brings about a completely different approach. It’s not so much the technique or those other things that we all aspire to. The main thing is that feeling, that conviction.”

Yet there’s another force at work here as well, something larger than oneself that players can reach for and one that often goes hand in hand with the church: family. This too arises over and over again in Memphis musicians’ stories, with such a diversity of what “family” actually means that it need not be reduced to a simple Norman Rockwell image.

Barry Campbell with John Black and Austin Bradley

Musical families have marked the evolution of Memphis music since before that history was written. Herman Green never knew his biological father, Herman Washington Sr., a player in W.C. Handy’s band who was murdered when Green was only 2 years old. But his stepfather, Rev. Tigner S. Green, played a major role in his love of music. Other Memphis families were even more legendary: the Newborns, the Jacksons, and the Thomases, from father Rufus to his three children, to name but a few.

The Whalums, of course, are a formidable musical force in this town, yet they are far from the only dynasty springing from a fortuitous union of both religious and filial continuity. Take the Barnes family: Deborah Gleese, daughter of Rev. James L. Gleese, was, for a time, a Raelette, one of the background singers for Ray Charles, before she married gospel singer Duke Barnes and family life demanded that she leave touring behind.

Converting to the Seventh Day Adventist Church, the couple sang and played around Memphis regularly, ultimately incorporating their children into the show. Today, the Sensational Barnes Brothers, brothers Courtney and Chris, are a gospel act in their own right on the newly minted Bible & Tire Recording Company, while their older brother Calvin is the Minister of Music at the Olivet Fellowship Baptist Church.

Seeing him lead the band this past Sunday was an excercise in polished euphoria. From the mellow background passages, bubbling under Dr. Geno Gibson’s sermon, to the band and choir syncing flawlessly with a spritely drum machine and video projections, the service was a master class in stage craft. In the context of references to young congregation members who had recently been murdered, and in Gibson’s unflinching critique of the New Jim Crow, the music’s shimmer was a welcome blast of ecstatic community.

Jonny Pineda

Jonny Pineda

Jason Clark

Mostly, the service created a spirit of inclusiveness, and, it turns out, the church band is itself a testament to such openness. Calvin Barnes remained a Seventh Day Adventist for years when he began playing for Olivet Fellowship, before finally joining the church where he works nearly a decade ago. This is not uncommon. Jason Clark, executive director of the Memphis-based Tennessee Mass Choir, puts it this way: “Sometimes it’s difficult to find the level of talent you need right within a congregation. Sometimes you have to be a part of a congregation that’s willing to support the music industry financially, and that doesn’t always come from your home church.”

In the case of the Olivet Fellowship (which splintered from the New Olivet Baptist Church some years ago), that openness to outside talent extended to allowing one young drummer to rehearse his secular band in the church during off-hours. Calvin Barnes recalls meeting the drummer’s bass player, a kid named DJ, whose father was a well-known bassist already. “The first time I met him, he was playing with this little group, kids really, and some of them were members of my church. DJ was probably around 12 and came in with his bass bigger than him, and when he played it was like ‘Oh. My. God.’ He wasn’t as good as he is now, but he was playing like a grown man. At that time he was super shy. But when the church ended up losing our bass player, we said, ‘Why not DJ?'”

Though DJ didn’t know the formidable gospel repertoire, he soon mastered it. Calvin nurtured both his idiosyncracies and his ensemble chops. “I really took him under my wing,” says Barnes. “And on the music tip, I would challenge him. Because he’s always been that avant garde-in-the-making type. So when the pastor gets up to preach, musicians typically go off to the side because they’re done for the moment. They just chill. Not him. He would sit there in his chair, turn his volume down, and start practicing bass. He’d do that through the entire sermon, every week. Over and over and over. And I would tell him, ‘You’re gonna be major.'”

Calvin Barnes, Minister of Music at Olivet Fellowship Baptist Church, on keyboards

As he coached the young bassist, little did Barnes realize that DJ’s idiosyncracies were what would lead him to greater renown. Some years later, DJ began posting YouTube videos of his more off-the-wall music, under the name MonoNeon. One such video caught the ear of Prince, who flew him to Paisley Park in Minneapolis to jam and record several times before the mega-star’s untimely death. Today, MonoNeon continues to ride that momentum, both with his own albums and in collaborative bands like Ghost-Note.

Church bands, it seems, are especially open to child prodigies. Jason Clark remembers well one young talent in particular: “When I played at Abundant Grace, close to 28 years ago, there was a young guy named Stanley Randolf, who was 9 years old. He was one of the most phenomenal drummers that I had ever heard. Now he’s Stevie Wonder’s drummer, to this day! We have quite a bit of those stories here.”

Clark himself is no stranger to being a prodigy nurtured by both a musical family and the church. Both playing in a church band and directing the Tennessee Mass Choir, which pulls talent from across the state to Memphis, he seems to have been destined for a life in music. “The choir was actually started by my mother, Fannie Cole-Clark, back in 1990. Next year we’ll be celebrating 30 years. Our mother passed away six years ago, so it was handed over to me when she passed. A lot of people remember her from back in the day, when she started the Fannie Clark Singers, produced by the late, great Willie Mitchell. It was a gospel group. I actually started out playing tambourine for the Fannie Clark Singers when I was 6 years old.”

Clark went off to a life in religious music and credits his success, in part, to time he spent at one of the city’s most pre-eminent musical ministries, Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church. “Dr. Leo Davis is one of the best Ministers of Music that I’ve worked under,” he says. “I know he single-handedly trained a lot of musicians here in the city. And to this day, they have probably one of the top five bands in the city. I think that’s due to his leadership.”

Now Clark’s an accomplished keyboardist, while his brother Jackie is a go-to bass player for the likes of Kirk Whalum and others. But for Clark, the luck of being born among musical folk is not a prerequisite for thriving in the church music scene. “No, not really,” he says. “There of course are a few like that, but there are some who are just gifted. There are some who went to school. That’s the beauty of church musicians. You get such a variety. That’s why our genre is more diverse than any other style of music. It encompasses jazz, to pop, to that gritty bluesy feel, to classical. I really credit that to the fact that not everyone grew up in church, just playing gospel music. So you get this whole eclectic feel within the gospel arena. There are just so many different beginnings to it.”

And, as it turns out, there are happy endings as well. While church bands can foster talent in the making, they can also offer a haven to great players who once toured the world. Such was the scene I stumbled upon at the historic Mt. Pisgah Christian Methodist Episcopal (C.M.E.) Church in Orange Mound, which only last month celebrated its 139th anniversary. Attending their service on that Sunday was like turning the calendar back a half century. On either side of the 90-year-old building’s proscenium, high above the altar, were two vintage Leslie speakers, hard-wired to a classic Hammond organ. At the keyboard sat Winston Stewart, longtime member of the Bar-Kays throughout their ’70s and ’80s heyday. Playing bass behind him was Barry Campbell, who was in demand as a New York session player for nearly 20 years, playing with the likes of Eric Clapton, David Bowie, and Quincy Jones. Together with drummer and singer Austin Bradley, guitarist John Black, pianist Davida Winfrey, and the earnest choir led by City Councilwoman Jamita Swearengen, they created magic.

As one friend noted, finding such talent in unassuming corners of the community is as Memphis as it gets. And it helped me appreciate the phenomenon of the church band as a haven as well as a hothouse for youth. As Campbell tells me, “When I was in New York, the music industry began to change. Everyone went for that MIDI programming thing, like with hip-hop and rap. And the rent in New York City kept going up. After a while I was like, ‘Why am I here?'”

So he returned to the community where he grew up. “It’s a church in the ‘hood,” he says. “It’s old-school. It’s a good church. Young people want that contemporary stuff, those mega churches with flat screens and big sound systems. But musically, at Mt. Pisgah we’re still kinda doing it the way they did it back in the ’60s and ’70s. We’re not really throwing in much of the jazz fusion that’s going on now. We’re more soul and blues-oriented. We don’t get into too much Kirk Franklin-type stuff because we don’t have a youth choir. Everybody in the choir is old enough to be my big brother or daddy or mama.”

Neither Campbell nor Stewart grew up playing in the church but came to it later in life. For Campbell, this was partly a practical matter. “Live music isn’t as popular as it once was. So a lot of musicians have gone to the church over the last 30 years. Once I came back, all my guys had a church gig. Every church had at least a bass drum and keyboard. Some churches even had synthesizers. Some had bands. I even knew white churches that had orchestras. It just expanded to where it’s a thing now.”

On this late autumn Sunday, I was glad it was a thing, as Winston Stewart coaxed waves of emotion from the Hammond organ in a minor key, playing even the drawbars’ shades of timbre deftly, while the bass and drums defined a slinky pocket. Though Stewart’s a relative newcomer to the gospel idiom, it was clear that his lifetime of music and soul was pouring out of those speakers, as one extended organ showcase piece after another evoked waves of blues-drenched sorrow and joy.

It was then that the Reverend Willie Ward stepped up and quoted Romans 10:17. “Faith cometh by hearing!” he declared. Still recovering from the reverberating wooden chambers of the organ, bass, drums, and guitar, topped with those soaring voices, I was inclined to believe it.

Edgar Mata

Edgar Mata  Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music  Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music  Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music  Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music