It took the painter Veda Reed years to lose the horizon. In her younger years, the Oklahoma native would make landscape paintings about two things: land and sky. “Being able to see where the sky meets the land has always made me feel safe,” said Reed in an artist talk on Sunday, at the opening of her show “Day into Night.”

Reed didn’t want to remain safe. She wanted to lose her bearings, to lose the question of perspective posed by a hard horizon line. So she did what she had to do: She looked up. She began to paint the moon, and the sun, and especially the clouds. She joined a cloud appreciation society and read every book she could find about altocumulus, mammatus, nimbostratus.

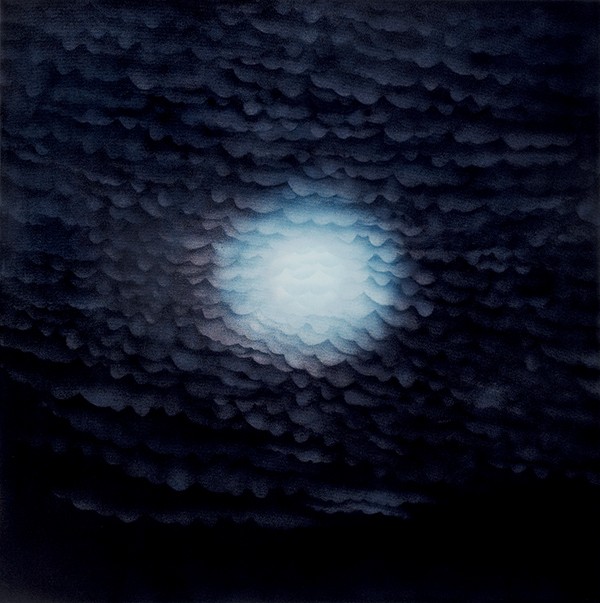

If this sounds simple, it is. Reed’s oil paintings of clouds, brokered by moonlight or dawn, are simple in the way that faith is simple. They start at the heart of the mystery. They don’t attempt to offer anything beyond what’s there, the there-ness being both the most basic and most complex thing possible.

Looking at Reed’s 2011 painting King of Clouds (Cumulonimbus Incus with Mamma) — a mollusk-like formation suspended on the canvas in rosy browns — a John Donne quote came to mind: “That then this Beginning was, is a matter of faith, and so infallible. When it was, is a matter of Reason, and therefore various and perplex’d.” Per Donne, there is something “so infallible” about these paintings, which are about faith and not reason.

Reed has the uncanny ability, honed over decades of focus, to use two or three colors to describe sun streaks, or a wreathe of light around a full moon, or a scrim of clouds in the early morning. Her 2013 painting, Sun Streaks, involves deep blacks cut through with jet streams of yellow light. The light appears to emerge from inside the depths of the sky, a feature of the darkness rather than a separate entity.

Nightfall: Clouds and Moon 2006 from Veda Reed’s “Day into Night”

A painting like Nightfall: Clouds and Moon has the improbable effect of making you feel not as if you are in front of the painting, but as if you are surrounded by it. Likewise, the pendulous, green pouches of cloud in her 2000 work, Mammatus II (the mammary cloud), are perhaps not the literal visual description of a storm — but they feel like a storm.

When I look at paintings, I often ask myself something along the lines of what’s behind this painting? Why did the painter choose to combine these elements, in this style, to make this image? Reed’s work did not make me wonder, even for a second, what was behind the image. The clouds she paints are not images. They are symbols. Like symbols, they express meaning where the language has failed or not yet been invented.

Said Reed on Sunday, “I’ve always been interested in nature and its cycles, and I began to want to paint those in a way that would allow people to pause and think about them.” She has succeeded, to say the least.

A note: This is my last art column for the Flyer. I’ve loved writing about art in Memphis for the past three years. Listening to Veda Reed talk about her art to a packed room this past weekend, I have to admit that I cried more than is maybe appropriate in an artist talk. The love that people have for Reed and her work epitomizes, for me, the way that people in our small art community support each other. I’m so happy to be from this city. So thanks for letting me write about your art, and for reading, even when I got it wrong.