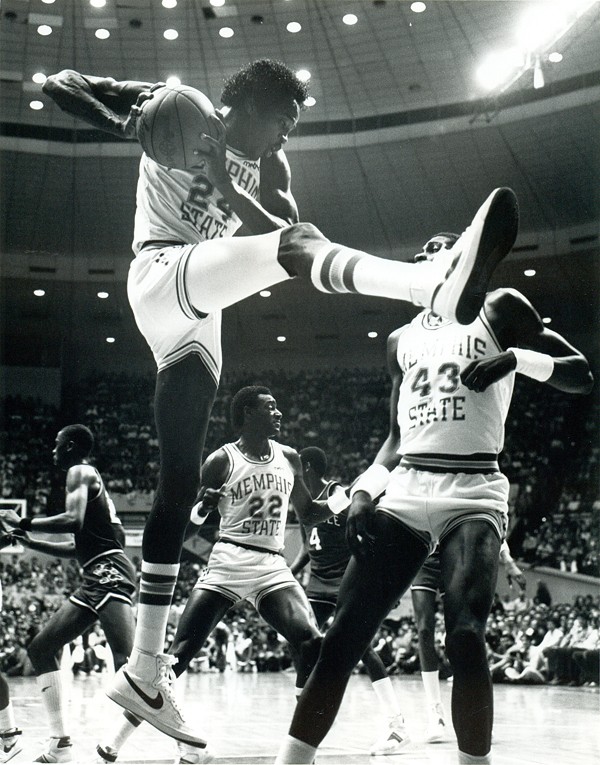

Disney will never make a movie about the 1984-85 Memphis State Tigers. A basketball team that went 31-4 under coach Dana Kirk reached the Final Four, only the second team in the program’s history to do so. A team headlined by power forward Keith Lee — a first-team All-America and still the program’s all-time leading scorer — beat archrival Louisville three times on its way to the national semifinals where it played the foil in the Cinderella story of eventual national champion Villanova. Thirty years later, though, that fabled team’s legacy remains an unlikely cocktail of pride and regret.

Keith Lee

Lee’s supporting cast was a quintet of locally produced players that made the team as distinctly Memphis as any before or since. Mitchell High School alum Andre Turner (then and now, the “Little General”) played point guard and was on his way to setting a Tiger record for assists (763) that stands to this day. Fellow junior Baskerville Holmes was a high jump champion at Westwood High School and is a fixture on history’s All-Name team. Sophomore William Bedford (Melrose) combined with Lee for a twin-tower presence down low. Freshmen Vincent Askew (Frayser) and Dwight Boyd (Kirby) received steady minutes from Kirk, filling voids left by the departed Bobby Parks and Phillip “Doom” Haynes. The Tigers were established national contenders, having reached the NCAA tournament’s Sweet 16 each of the previous three seasons.

The Tigers won 17 of their first 18 games (losing only at South Carolina) and rose to no. 3 in the national rankings. They only lost two more regular-season games, one understandable (at 13th-ranked Kansas), the other mysterious to this day (at Detroit; look it up). They won the Metro Conference tournament at Louisville, beating their archrivals in the semifinals before edging Florida State in overtime for the title. As the second seed in the NCAA tournament’s Midwest region in Houston, Memphis State beat Penn and UAB (then coached by Gene Bartow, who coached the Tigers to the 1973 Final Four). They then beat Boston College (with Michael Adams) and Wayman Tisdale’s Oklahoma Sooners in Dallas to reach the Final Four.

The team’s run ended in Lexington, Kentucky, on March 30, 1985, when Rollie Massimino’s Villanova Wildcats — an eight seed — managed to throttle Lee (10 points), Bedford (8) and friends in a 52-45 upset. Not for 21 years would another Memphis basketball team win 30 games in a season.

“College was the most fun part of my life so far,” says Askew. “The friends I made, the basketball. Dwight Boyd won a championship his senior year [in high school], and man, I heard about that our entire freshman year. We had better talent [at Frayser], but they won a championship! It’s not always about talent.”

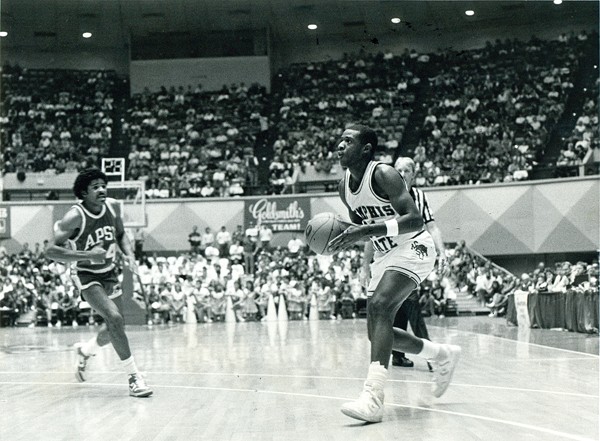

While Askew was a starter by the team’s third game of the season, his roommate Boyd found the adjustment to college ball more rigorous. “I had some deficiencies,” he says. “When [opponents] watched film, they saw this guy who couldn’t go right as strongly. But going against Andre Turner in practice every day, going against Vincent Askew, Baskerville Holmes, and Keith Lee . . . my confidence started to grow. Middle of the year, I came off the bench at Louisville and scored 16 points, had a monster dunk. From there, it was smooth sailing.”

Being essentially an all-star team of homegrown talent, the ’85 Tigers congealed quickly and put aside any lingering rivalries from high school. “There was a lot of pressure on us to succeed,” says Boyd. “We were recruited all across the country, then we went home to the community where we grew up. At that time, I represented East Memphis. That builds character. You didn’t have to tell me to go to the gym to work on my jump shot. Let’s show these cats around the country what Memphis is about. We didn’t need to be from New York or Chicago. It was one common goal.”

“We were so close,” adds Askew. “Even if certain guys didn’t hang together off the court, we had a bond. We used to go to each other’s houses and eat. We’d get back to the dorm and talk about what we’d seen at those houses. We knew each other’s moms. It was all in fun.”

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

Andre Turner

Courtesy U of M

Courtesy U of M

Andre Turner

“More than anything,” says Turner, “it was togetherness. We’d finish practice, shower, and eat. Then we’d be at the complex, playing ping-pong, competing. It was all in love, every last bit of it. Nobody took offense to anything. You’d laugh off [the barbs], try and keep things together.”

Turner and Holmes roomed together for four years after battling each other fiercely in high school. “Big time rivals,” says Turner. “We went at it. But then we had an opportunity to play together. How much fun is this? We embraced it. Bat was my guy. [Holmes’ nickname was “Batman.”] People knew if they got into it with Bat, they were about to get into it with Andre. If you came into 305 — our room number — you came in with respect.”

The team’s familial bond took on special meaning for Turner when his father died that February after a long battle with liver cancer. Turner missed but one game — the loss at Kansas — before returning to the floor. “My game elevated after that,” says Turner. “My dad was a huge inspiration, and I dedicated the rest of my career to him. It was tough. He never got to watch me play professionally. That’s where the leadership came from, though. I saw him get up every morning at 5:30 and head to the workhouse.”

His position may have been power forward, but Keith Lee was the center of the Tiger universe. To this day, Turner is acknowledged as the team’s vocal and emotional leader. (“Andre never lost a sprint in practice,” says Askew.) But this was Keith Lee’s team.

Already married and living in family housing, Lee played the role of big brother for his teammates, particularly the younger ones. “I had played with Keith in the [1984] Bluff City Classic,” says Askew, “so the intimidation factor was over. But he was the most intimidating person I ever met, including in the NBA. I used to be scared to talk to him. Later on, I dated his wife’s sister.”

Lee never reached All-Star status as a pro, but question his talents at the risk of some blowback. “I played with Tim Hardaway, Chris Mullin, and Gary Payton,” says Askew. “Some Hall of Famers. Keith Lee is the best player I ever played with. He could do everything. He could rebound, pass, shoot. He was smart. He used to dominate practice.” Askew likes to tell the story of the freshmen getting Lee to join them for one scrimmage against the first-teamers, a challenge Askew offered Turner. Lee and the youngsters won big.

“Keith likes to keep to himself,” says Turner, “but with us, you talk about cracking jokes and laughing … especially on the road and at practice. He was a great teammate, and great friend. I got two tickets on the front row to watch Memphis State and Louisville Keith’s freshman year. He had 30 [points] and 13 [rebounds]. I wanted to play with a special player.”

Lee possessed the most prized intangible in basketball: He made his teammates better. “His hands were so soft,” says Turner. “I threw so many bad passes that Keith caught. Incredible hands. He’d get double-teamed, find a teammate, layup. Great court vision. His free-throw percentage was better than the guards’ [percentages].”

“We knew who to get the ball to,” adds Boyd. “We didn’t have to guess. Keith Lee was by far the best big man I played with. He made it a lot easier for me. He took the freshmen by the hand, calmed us down.” Lee averaged a career-high 19.7 points as a senior, though his team-leading rebounding averaged dipped to under 10 (9.2) for the first time, in part due to Bedford’s own rebounding skill. He left the program with 2,408 career points and 1,336 career rebounds, records that stand to this day.

[Lee did not respond to interview requests for this story and did not appear with his teammates when they were honored last Saturday at FedExForum.]

The players stand by their since-disgraced coach, claiming they saw no indication of any misdeeds on the part of Kirk (more on those later). Just a loyal, passionate, and skilled basketball tactician.

“He was probably the best three-minute coach — at the end of a game — that I’ve ever been around,” says Boyd. “He put everybody in position to succeed. He provided me with an opportunity to get a scholarship; changed my life forever. All the things he had going on outside … I didn’t have a clue. We spend so much time trying to judge individuals for their downfall, and we forget about some of the good they provided. I judge Coach Kirk only for the experience he provided me.”

Turner connected easily with Kirk, as the two saw the game the same way, thus the Little General tag for a freshman point guard. “I took pride in outworking everybody,” says Turner. “I was the smallest guy; I had to be the fastest. If I hit the court and I felt someone wasn’t giving all they could give, I didn’t hesitate about saying something. Go sit on the sideline. You’re hurting us.”

Kirk had command of the huddle, according to Turner. “Coach Kirk knew basketball,” he says. “And he knew us, how to get the most out of us, as individuals and as a team. He made sure we got what we needed when it came to preparation. And he was blessed to have assistants like Larry Finch and Lee Fowler. They knew the game as well.” Boyd remembers Finch as the “bad cop” on the bench, letting players know — with volume — when their play slackened. When Finch finished the scolding, Kirk — the “good cop” — would signal for the player to re-enter the game.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

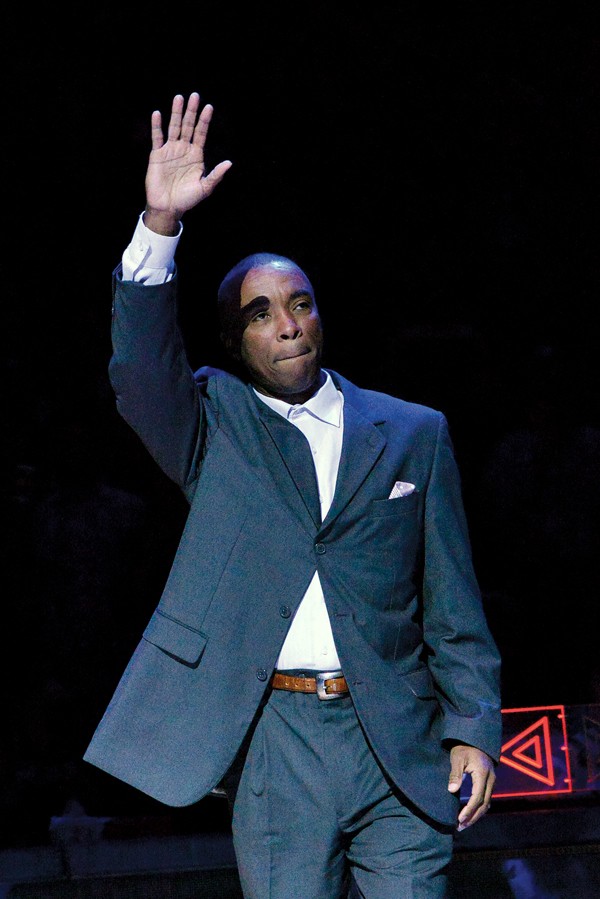

Vincent Askew

Courtesy U of M

Courtesy U of M

Askew was on the verge of signing a letter of intent to play at Tennessee, at the time coached by Don DeVoe, when he got a life-changing phone call at home, directly from Kirk. “I verbally committed to Tennessee the night before I signed with Memphis State,” says Askew. “One of my uncles was gonna kill me. But Coach Kirk called and said, ‘Hey bud. You ready to sign?’

“I hear so many people talk bad about his coaching,” says Askew. “Maybe it’s the trouble he had off the court. I played for Larry Brown, George Karl, Don Nelson. Coach Kirk was right up there with them.” Askew mentions a late-game defensive switch in the Tigers’ second-round NCAA tournament game against UAB in which Kirk had Askew take over the assignment of guarding Blazer star Steve Mitchell. The switch initially angered Turner (who had been guarding Mitchell), but the Tigers won in overtime. On a shot by Turner.

Villanova was better than the Tigers … for 40 minutes on a single Saturday at the 1985 Final Four. When asked if his team would have won a five-game series with the Wildcats, Turner smiles and somewhat dodges the question: “Let me ask you this: Would Georgetown have won a five-game series with them? That was destiny.”

As disappointing as the loss to Villanova seemed at the time, it was mere prelude to the sorrow associated with this team. The NCAA found Kirk guilty of several infractions — among them cash payments to Lee — and in 1986 stripped the Tigers of the Final Four appearance. Dismissed after the 1985-86 season, the coach later served prison time for tax evasion. (He died in 2010.) As for Kirk’s players, the years after 1985 brought as much darkness as light.

The Chicago Bulls chose Lee with the 11th pick in the 1985 NBA draft, but knee injuries ended his career just four years later. Bedford earned third-team All-America honors as a junior and was chosen by the Phoenix Suns with the sixth pick in the ’86 draft. Substance abuse, though, led to a year-long suspension and Bedford was out of the NBA before his 30th birthday (though with a championship ring from his 1989-90 season with Detroit). He served eight years in prison (2003-11) for drug possession. Turner bounced among seven NBA teams over six seasons before crossing the Atlantic to play in Spain. Askew had the best pro career among his ’85 teammates, playing in 467 NBA games over 11 years, most with the Seattle Sonics. But then in 2008, at age 42, he was arrested in Florida and accused of having sex with a minor (he was given three years probation). Reserve forward Aaron Price — a classmate of Lee’s — was shot and killed outside his home in West Memphis in 1998, a crime that remains unsolved.

Saddest of all, perhaps, is the story of Holmes. Drafted by the Milwaukee Bucks, he never took the floor in the NBA. After a short playing career in Europe, Holmes returned to Memphis, finding work as a truck driver. On March 18, 1997, he shot and killed his girlfriend after an argument, then turned the gun on himself.

“Bat had a huge heart,” says Askew. “He was a big-time leader, led by example. His heart was as big as the Mississippi River.”

“Bat was so easy to get along with,” adds Boyd. “He was always smiling. But when he hit the floor, he was all serious. Great individual to be around. You know individuals, but you don’t really know them.”

“The Baskerville situation cut a little deeper,” says Turner, who was preparing for his Spanish league’s playoffs when he got the news. “I didn’t practice. I needed time to myself. My family was there, so that helped me a great deal. It was a shock. We would always get together when I got back home. I hadn’t seen any signs that depression had set in with him. He always had your back. You could count on him.”

Askew is just as mystified by Price’s violent death. “I hadn’t seen Aaron since college,” he says. “That was a shocker. In college, Aaron never drank, never smoked.”

Askew blames no one but himself for the trouble he found seven years ago. “It was embarrassing,” he says. “I had to sit down and explain to my kids. But it got me closer to God. I was raised in the church, but I got outside, trusting people. It was my fault. That’s why I do what I do now. I bring it up when I speak to groups. You never know what kind of decisions kids have to make. Sometimes the tough way is the only way. Say no to friends who don’t mean you any good. Have your own mind.”

He founded the Vincent Askew Skills Academy last month, promoting the operation with a distinctive acronym: EPIC (European Preparation Intensity Coordination). “It focuses on teaching kids how to set goals in life,” he says, with basketball as the foundation. “When I went to Europe as a player — Italy and Greece — they really taught the game, the fundamentals, the little stuff. Instead of just rolling the ball out like it’s a P.E. class, they really teach them. When I leave this earth, I want to leave something solid, something to give people hope.” Askew’s clinics are held at Raleigh Assembly of God.

The enduring link among the stars of that Final Four team: their hometown, Memphis. The reclusive Lee — a native of West Memphis, all the way across the river — completed his degree studies (in 2008) and is now the head basketball coach at Raleigh-Egypt High School. After playing professionally in Spain for 15 years, Turner is an operations specialist for Shelby County Schools and an assistant coach at Mitchell. (Turner married his high-school sweetheart, the former Desma Hunt, who also played basketball at Memphis State. The couple has five daughters, but Turner finds himself cheering soccer players.) Upon being released from prison in 2011, Bedford returned to Memphis. He got married in 2014, now works for a car dealership, and has volunteered as a mentor with Shelby County Juvenile Court. After 22 years with Pepsi, Boyd is now director of the M Club, his alma mater’s athletic alumni association.

Sports history is measured in the fabled record book. And you’ll find record books that ignore the 1984-85 Memphis State Tigers. After all the team has been through over the past three decades, such an omission seems more and more careless to history.

“We played in the Final Four,” Boyd emphasizes. “As far as it being vacated, I hate that. But I still have my Final Four ring. You can’t edit history.”

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

Dwight Boyd

Courtesy U of M

Courtesy U of M

Dwight Boyd

“When it happened, it hurt momentarily,” says Turner. “But it doesn’t hurt to this day. I know what we accomplished. The blood, sweat, and tears. I know what went into it. You can’t take away all the hard work, all the fun we had, what we built together. It was a great time. The biggest thing: we were all from [Memphis]. It’s like we had been waiting for each other. And we grew together.”

“That should be the poster team for real life,” says Askew. “Good decisions, bad decisions. Successful people, and people still trying to find their way. But at the end of the day, we’re all family.”