Are the citizens of Memphis and Shelby County — troubled with decades of problematic and even botched election results — really about to acquire a new, improved means of expressing their will in the forthcoming August and November election rounds?

That question may be answered this week, as the Shelby County Commission decides whether to accept or overrule the judgment last week of Election Administrator Linda Phillips and the Shelby County Election Commission (SCEC) — apparently in favor of ballot-marking devices marketed by the ES&S Company, a monolith of the election-machine industry. The name of the chosen manufacturer was not explicitly revealed last week — “Company 1,” was how it was called in discussion — but several references by Phillips to the “thermal paper” uniquely employed by ES&S for production of machine receipts, were something of a giveaway.

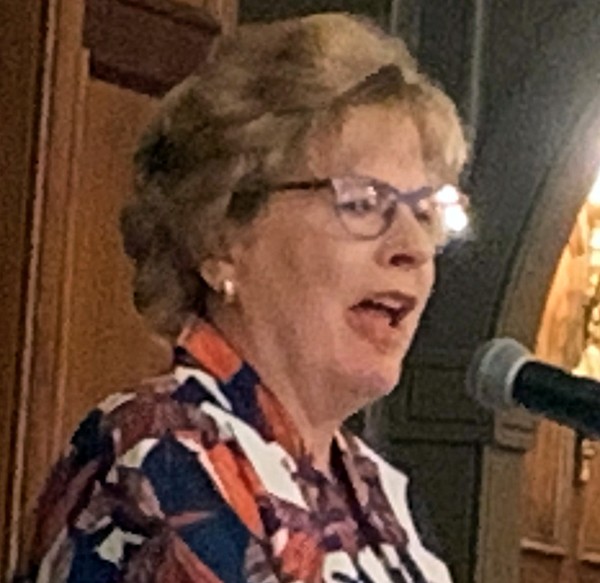

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Election Administrator Linda Phillips

The Shelby County Commission, which has the responsibility of paying for the machines (or not), had voted twice previously in favor of hand-marked ballots instead, on several grounds, including cost, transparency, and invulnerability to ballot-hacking. And an aroused contingent of local activists, abetted by a network of nationally known election adepts, is prepared to insist on that choice.

Theoretically, the SCEC voted last Thursday to accept something of a compromise resolution from Election Commision member Brent Taylor, one of the three Republicans on the five-member body. Taylor accepted Phillips’ recommendation on behalf of ballot-marking devices but proposed that voters in each precinct be offered, much in the manner of the grocer’s “paper or plastic” choice, the alternative of a hand-marked ballot. That was seemingly enough to win over Democrat Anthony Tate. But not Bennie Smith, the other Democrat and an election-security professional who is one of the sparkplugs of the case for hand-marked paper ballots.

The bottom line is that, despite last week’s 4-1 vote by the Shelby County Election Commission in approval of ballot-marking devices — again, presumably those manufactured by ES&S — the battle isn’t over yet. Hardcore proponents of hand-marked paper ballots, who have been highly motivated and organized from the beginning, are looking ahead to the prospect that the Shelby County Commission, whose duty it is to pay for and transact any purchase of voting-machine equipment, might override the stated choice of the Election Administrator and SCEC.

The county commission has put itself on record twice as wishing to purchase a system employing hand-marked paper ballots as the most cost-effective, transparent, and unhackable way to carry out an election. As the specter of COVID-19 began to make itself felt, the paper ballot adherents have also emphasized the lesser likelihood of viral infection via a paper ballot used singly than for metal used over and over by a sequence of individuals.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Commissioner Van Turner

One of the more dedicated believers in the paper ballot concept is Democratic County Commissioner Van Turner, who some weeks ago at a commission meeting was involved in a verbal exchange with Election Administrator Phillips, who was adamantly insisting on her preference for ballot-marking devices.

“We can vote down the funding,” Turner pointed out.

“We can sue you,” Phillips retorted.

Legal Aspects

Though conflict-of-interest and disclosure issues are involved in the dispute, the heart of the matter may well be fundamentally different ideas about the right to vote. Though both sides in the current controversy make claims that the system they advocate will save money and achieve accurate results, the question is deeper and more essential than that.

There may, in fact, be something more than an incidental correlation between the method we choose to cast our ballots and the degree to which the franchise is made available to the maximum number of people. As one instance of that, the partisans of hand-marked paper ballots tend to favor the maximum use of voting by mail for anticipated absenteeism and other reasons, especially in a time of enduring fears regarding the COVID-19 virus. One such advocate is Steve Mulroy, law professor at the University of Memphis and a former member of the Shelby County Commission and one of the leaders of the local activists seeking hand-marked paper ballots.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

U of M law professor Steve Mulroy

Mulroy first came to public attention more than a decade ago when he was an early advocate locally of a paper trail for the purpose of double-checking, if need be, the votes cast in an election. The concept is now accepted virtually everywhere, and the idea of scanners to provide such a paper record of ballots cast is now built into both of the rival systems being considered for Shelby County’s new voting process.

Even as Mulroy is joining with others to urge the county commission to expand its fiduciary intent and resources for the purchase of a hand-marked ballot system, he has filed suit in Chancery Court in Nashville against relevant public officials of the state of Tennessee — Governor Bill Lee, Secretary of State Tre Hargett, state Coordinator of Elections Mark Goins, and state Attorney General Herb Slatery — seeking relief for several named individuals and organizations from state regulations impeding or prohibiting their wish to vote absentee by mail in the face of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

Court is where the voting machine case could end up, too. The partisans of hand-marked paper ballots are hopeful that the seven Democratic members of the county commission who have voted twice to endorse the purchase of such a system will stick to their guns and vote to overrule the Election Commission’s official recommendation. Such a vote could happen at the county commission’s next regular public meeting, on May 18th. Or it could come earlier via a special called meeting.

In the event such a vote does occur, it is probable that the issue would be contested legally. A first step would be Chancery Court locally, where, as County Commissioner Turner, a proponent of hand-marked ballots, sees it, the odds would favor his side. “After that, who knows?” said Turner, who foresees a round — maybe several — of appellate testing, as well as a possible action supporting ballot-marking devices by a reconvened state legislature with its Republican super-majority. “However it goes, I’m with it to the end,” vowed Turner, who said he thought the other six Democratic commissioners favoring hand-marked ballots would persevere as well. (It should be noted that the party-line aspect of the current controversy owes much to a public letter from GOP state Senator Brian Kelsey addressed to the three Republican SCEC members insisting on their support for ballot-marking devices.)

Administrator Phillips is very much a true believer for her side. She has made numerous public statements disparaging paper ballots and extolling ballot-marking devices, and, even as her original RFP (request for proposal) went out to potential vendors, she had an op-ed published on behalf of such machines. And she has made frequent public statements alleging that voter error is a rampant feature of paper ballots and, even more sensationally, told a county commission meeting recently that voter fraud occurred “100 percent” in the realm of paper ballots.

Mulroy, who has authored numerous serious papers and a book on the kaleidoscope of issues relating to voting, promptly debunked Phillips’ assertions, producing evidence that such paper-ballot fraud is hard to authenticate anywhere and has been non-existent in Tennessee. Further, Mulroy cited studies demonstrating that the rate of voter error was no higher in paper voting or in absentee ballot counts than in touch-screen voting. Significantly, he used research performed by the conservative Heritage Foundation to buttress his conclusions in both cases.

A Matter of Bona Fides

Adherents of paper ballots have been at pains of late to question the bona fides of Phillips’ professed positions, citing her own relationship — and that of her family members — to companies with whom she has arranged contractual relationships. Inasmuch as her preferred vendor for the new ballot-marking devices she wants for Shelby County is apparently ES&S, it may or may not be relevant that, as her PR assistant Suzanne Thompson acknowledged in a recent communication, one of Phillips’ two sons, presumably Andrew, “worked for ES&S,” adding, “He’s no longer employed there.”

Documentary evidence does establish that Andrew Phillips, along with another Phillips son, Chris, did work at the voting-software company Everyone Counts in 2017, when Shelby County, during Phillips’ first year as election administrator , concluded a $1 million-plus contract with that company, for the purchase and maintenance of voter-registration software. Controversy surrounds the history of that contract, first of all, since not only the two Phillips sons but Phillips herself had been an employee of Everyone Counts. Everyone Counts was, in fact, her immediate past employer at the time she took the job of Shelby County election administrator.

At the time, Everyone Counts seems not to have been regarded as a leader in its field. During the first year of the Shelby County contract, in fact, Everyone Counts suffered financial difficulties and was purchased by a company called Votem, which took over administration of the voter-registration contract. In short order, Votem would divest itself of the Shelby County contract, passing it on to a third company, KnowInk.

Coincidentally or not, Chris Phillips, one of Linda Phillips’ sons, would end up in the service of each of those companies in turn — first Everyone Counts, then Votem, and finally KnowInk, where he remains today. Meanwhile, Shelby County has continued to pay an annual maintenance fee to whoever held the contract, and has purchased KnowInk e-poll books for $175,000 on a sole-source contract.

The issue of family connections is not the only one that has arisen regarding that voter-registration contract, which was Linda Phillips’ first major action in the service of Shelby County. There is some indication that she may have waived the duty of keeping her commission members sufficiently informed about the vendor or the other relevant facts regarding the contract.

Prior to concluding that 2017 contract, Phillips, who had been hired by Shelby County in 2016, went through the motions of asking Marcy Ingram, then the ethics officer in the Shelby County Attorney’s office, a series of questions, including those of whether her own past relationship with Everyone Counts needed to be disclosed and whether her son’s employment at the company should be disclosed as well.

Attorney Ingram’s answers were succinct: “As you are involved in the evaluation of the proposals,” she said, Phillips needed to make disclosure in both cases “to the other evaluators” to avoid “an appearance of impropriety.”

In her query of Ingram, Phillips had offered this assurance: “I’m not going to be making the final decision on what to purchase; that will be the Election Commission decision to recommend the vendor.” [Our italics]

There is no record in the minutes of Shelby County Election Commission meetings or elsewhere to suggest that the commission was in fact invited to pass judgment on the vendor. Norma Lester, an election commissioner at the time, is adamant about that and affirms, too, that there were no disclosures to the election commission of the sort mandated by Ingram. Phillips’ own PR consultant, Suzanne Thompson, explains the letting of the contract thusly:

“For the purchase of the VR equipment, a scoring machine [sic] made up from county IT reps and the election commission each ranked the equipment. Each member rated the system independently. She [Phillips] didn’t make a recommendation for the Voter’s Registration System because it was all up to the folks in purchasing.”

In short, while various IT technocrats may have had a shot at “evaluating” the contract, the Shelby County Election Commission itself seemingly did not. This may or may not be a problem of substance. It is certainly one of optics.

Also in the optics category is another odd circumstance: John Ryder, the veteran Shelby County Election Commission attorney who doubles as a vintage Republican Party eminence, was revealed recently to be sharing office space with the Nashville firm of MNA Government Operations. The head of that firm is Wendell Moore, a longtime Ryder friend, who lobbies for the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce and for ES&S, that major player in the election-machinery field, and the ultimate choice of Linda Phillips and a 4-1 majority of the Election Commission as the contractor of Shelby County’s new voting system.

Once the matter of his office-sharing became public, Ryder argued that his presence in the Nashville office of MNA was due to the fact that his law firm, Harris-Shelton, rented space there and that he had no working relationship with either MNA or its client ES&S. He said further that he had no knowledge of the then-active RFP for Shelby County voting machines nor any of the vendors seeking the county’s business, and therefore he had seen no need to make any disclosures.

Left hanging over the affair in the aftermath, and never quite explained, was photographic evidence that, in two different versions of the glass register in the lobby of the Bank of America building in Nashville, Ryder was listed as an associate of MNA.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Election Commission in session

“Slimy Tricks?”

One thing is incontestable: As already indicated, ES&S, which absorbed its main rival, Diebold, some years ago, is a major player in the election-machinery business, a veritable titan. Critics of the company see it as an industry giant squelching would-be competitors and running rampant over contractual and constitutional processes in the jurisdictions where it operates.

Voting rights activist Susan Pynchon, a Floridian who, with local activist Erika Sugarmon, has organized several recent Zoom sessions on the voting-machine issue, has compiled a lengthy list of articles pertaining to the company’s activities nationwide. They run from charges of bribery to criminal negligence to playing fast and loose with contractual obligations to error-prone hardware and undependable software.

As a sort of distillation of all that, U.S. Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), in a recent Zoom seminar on election security, said that ES&S “uses every slimy trick in the book” to get states to buy “overpriced, insecure voting machines.”

That, of course, is one side of the issue. ES&S has its partisans, too, who see the company as the industry standard, inveighed against as much for its success as for any actual misdeeds. For the record, ES&S markets a hand-marked paper ballot system as well as its line of ballot-marking devices, though it more aggressively pushes the latter. The SCEC’s recent RFP saw three companies competing for Shelby County’s business: ES&S, Dominion Voting Systems, and Hart Voting System.

The Next Step

The next step in the purchase process will see Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris formally acknowledging the receipt of SCEC’s recommendation and signing an order for the Shelby County Commission to arrange a purchase for new machines to be used in August and thereafter. Word is that he will leave it to the county commission to accept the SCEC recommendation or make its own choice. If it does the latter, presumably it would opt to accept the low bid from among the various bids received in response to Linda Phillips’ RFP. And, as indicated, such an action might well be subject to legal action.

In any case, at some point in the near future, Shelby County stands to be outfitted with new voting devices, hopefully in time for the August election round. Even if human disputation is off the table by then, there might still remain the issue of whether the COVID-19 virus will remain persistent to the point that a truly serious urgency will attach to Mulroy’s aforementioned suit to allow the unimpeded use of “no-excuse-needed” mail-in ballots. For the record, those would be hand-marked.

…

Widely Differing Estimates

Election Administrator Linda Phillips and local activists for hand-marked paper ballots have difficulty agreeing on many things — notably the respective costs to Shelby County of the kind of new voting machines each prefers.

Phillips reckons the immediate purchase costs of new ES&S ballot-marking devices, which she favors, to be $7,160,000, as against $8,150,000 for a hand-marked ballot system. She sees the 14-year extrapolated cost of maintaining the hand-marked system to be $24,785,000, compared to $9,415,000 for ballot-marking devices.

The local advocates of hand-marked ballots, on the other hand, see their system as costing only $3,039,314 up front, with annual maintenance expenses of only $612,564, while they see the ballot-marking machines favored by Phillips to have an initial cost of $8,268,314, with annual expenses thereafter to be $885,203.

Not only different systems, but different vocabularies for figuring costs. No wonder this particular twain can’t meet.