Mississippi took its 16-year battle against Tennessee for water rights to the U.S. Supreme Court Monday and Justices compared the issue to wild horses in Mexico and fog over San Francisco.

John Coghlan, attorney for the state of Mississippi in the case, said the court should reject the Special Master’s conclusions to the case. Last year, the judge said, basically, that Tennessee has not been stealing water from Mississippi.

However, Coghlan said the case is not about whether or not Tennessee is asking more than its fair share of the water. He said the Supremes should focus on another question: Can Tennessee control groundwater while it’s located in Mississippi’s sovereign territory?

“Even if the aquifer is an interstate resource, Mississippi still possesses sole and exclusive control over groundwater within its sovereign territory, as recognized in [Tarrant Regional Water District versus Herrmann] and ensured by the Constitution,” Coghlan said. “And [Tennessee] cannot force groundwater across the border without violating this sovereignty.”

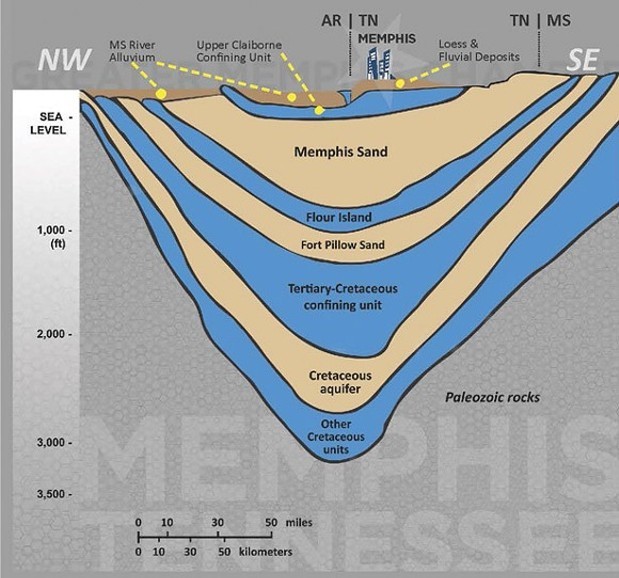

In questioning by Justice Clarence Thomas, Coghlan admitted that the Tarrant decision was a “cross-border situation.” But this case is, also, he said, as Tennessee’s “wells are physically located in Tennessee, but the pumping is physically crossing the border, unnaturally changing the pressure levels in this aquifer.”

Justice Thomas replied, “But couldn’t Tennessee make the exact same argument about you? Couldn’t Tennessee, Arkansas, Missouri all make the same argument that whenever you pump you’re causing similar problems for them?”

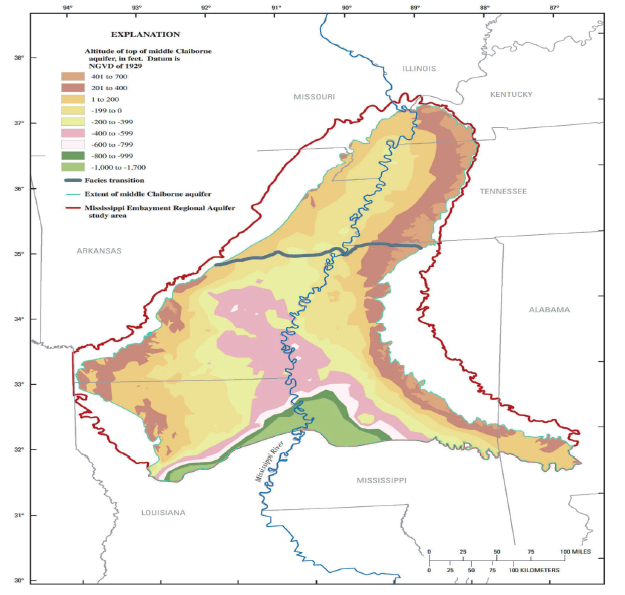

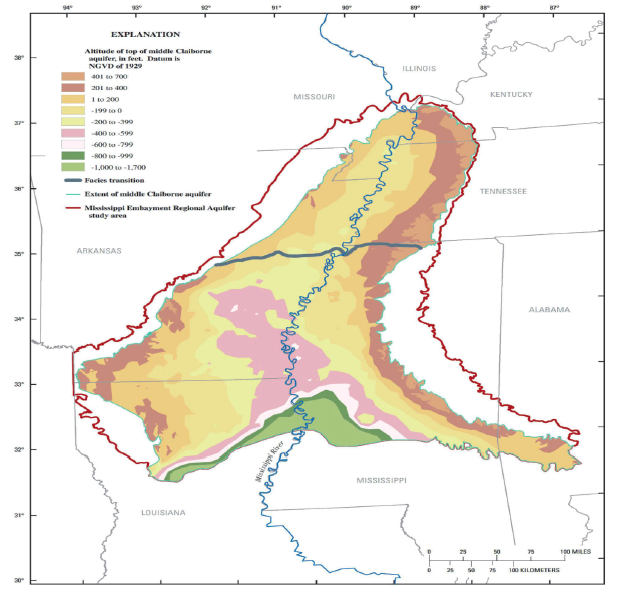

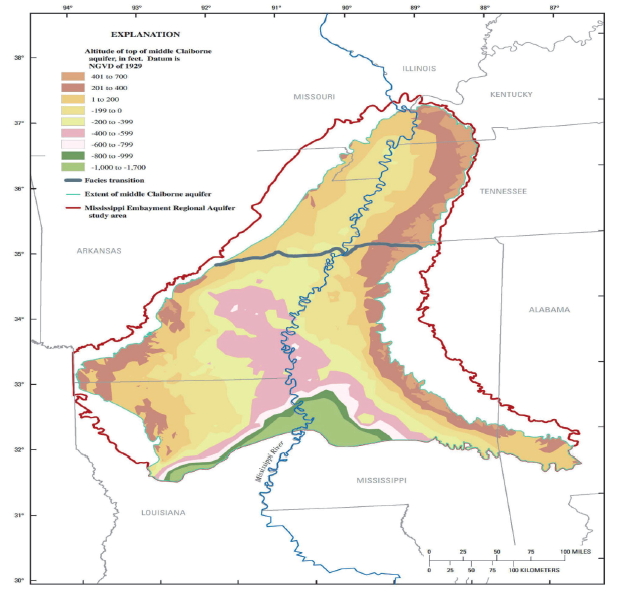

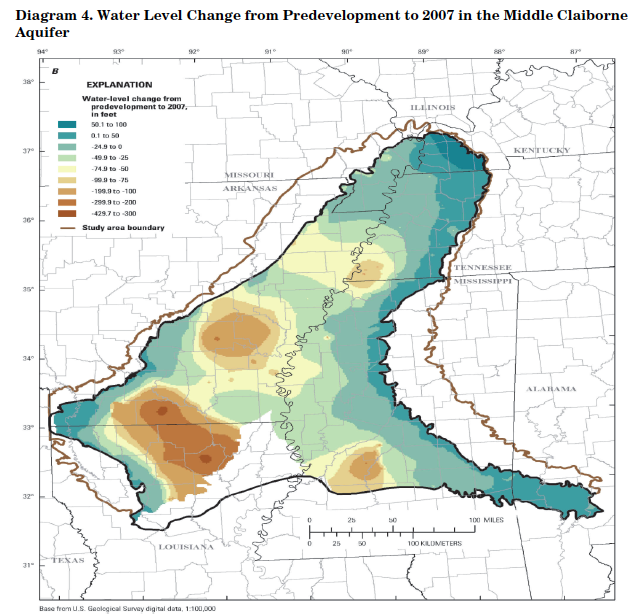

David Frederick, attorney for Memphis Light, Gas and Water in the case, told the court that Tennessee has lawfully pumped water from the Middle Claiborne Aquifer for more than 130 years. Traditional water-sharing rules don’t apply in the case and, therefore, Mississippi’s claim for $600 million in damages should be dismissed.

“The undisputed facts are the aquifer’’s water volume in the greater Memphis and northern Mississippi area has changed very little in the past 100 years,” Frederic said. “The aquifer is fully saturated and in a state of equilibrium, and Mississippi has increased its own pumping dramatically and can extract all the water it needs.”

Chief Justice John Roberts clarified that Mississippi’s argument goes past equitable apportionment, the equal sharing of natural resources that flow between states. Coghlan agreed that it did, as Tennessee was reaching across its border and exercising control in waters located in Mississippi.

Coghlan conceded that water in the aquifer flowed from Mississippi into Tennessee. But he argued it was irrelevant whether or not it was classified as interstate water to be shared.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor reminded Coghlan of the case’s long legal history and asked, “When is enough enough?”

“You’ve been litigating this case for over 16 years,” Sotomayor began. “You started in the Fifth Circuit. You went to the district court, you went to the circuit court; both courts told you you’ve got to seek equitable apportionment.

“You came here in 2010. We tell you the same thing. Now this is the third time you’ve done this. This time you explicitly disclaim any claim for equitable apportionment. When is enough enough? When should you be stopped from amending and seeking equitable apportionment, assuming you lose?”

Coghlan explained the case is relevant still as it is for future damages, not rectifying not seeking damages for the past. This is, in part, he argued, why simply sharing the water is the wrong legal remedy. It doesn’t address the sovereign control of the water.

If the court ruled against Mississippi in the case this time around, Coghlan explained to Justice Sotomayor that, yes, the state would want the option to change its argument and pursue the matter in courts in the future. He said, we would want to obtain “whatever relief is possible for Mississippi.”

The Justices then began comparing the water that flows beneath Mississippi and Tennessee to natural resources that flow freely in other states.

Chief Justice Roberts: “In the western states, they have these, I don’t know, wild horses or wild burrows, whatever they are, and they don’t obey the state lines and they’re wandering around and they — let’s just say they go from, you know, New Mexico to wherever.

“Let’s suppose that they’re — I know they’re pests, I guess, in some places, but let’s suppose they’re a valuable resource. If they were in Mississippi and crossed into Tennessee and Tennessee seized them at that point, would that be damaging Mississippi, or could Tennessee say, ‘Look, they’re on our territory, they’re under our physical control. We can exercise dominion over them, period’?”

Justice Stephen Breyer: “My understanding — and you have to — it’s very elementary. I mean, I think water falls from the sky. Some of it’s evaporated back. Others of it goes into oceans or lakes or streams. A huge amount goes underwater — underground. It’s groundwater, and it runs all over the place. That’s why I like the wild horses. My idea of that groundwater is it’s going all over the place.

“San Francisco has beautiful fog. Suppose somebody came by in an airplane and took some of that beautiful fog and flew it to Colorado, which has its own beautiful water — air. And somebody took it and flew it to Massachusetts or some other place. I mean, do you understand how I’m suddenly seeing this and I’m totally at sea? It’s that the water runs around. And whose water is it? I don’t know. So you have a lot to explain to me, unfortunately, and I will forgive you if you don’t.”

At this point, Coghlan explained that he’s not arguing that Mississippi owns the water. He said he’s arguing the state has the right to control the water while it’s within the borders of the state. Tennessee, he said, should not have the right to control it, by pumping it while it’s under Mississippi ground.

Chief Justice Roberts looked to the future of the case, noting that, if Mississippi won the suit, then Tennessee could bring a counterclaim with the exact same argument: that Mississippi was controlling water under its sovereign border. Coghlan agreed.

Roberts said if Tennessee did sue, “The normal thing would be [that] I’d take whatever … Tennessee owes you, whatever you owe Tennessee, and set it off against the other.” Coghlan agreed and Roberts said, “That starts to sound a lot like equitable apportionment.” Coghlan said that remedy would “be similar to equitable apportionment.”

In the end, the court was skeptical of Mississippi’s argument that it owned the water “simply by virtue of having passed through Mississippi’s territory,” said Frederick Liu, who filed a brief supporting Tennessee on behalf of the federal government.

The court also worried the case could set a precedent. If Mississippi prevailed and Tennessee had to pay for water in the future, that other states would begin suing one another for water rights.

The case was submitted for an opinion Monday.

Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber

Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber

U.S. Supreme Court

U.S. Supreme Court  U.S. Supreme Court

U.S. Supreme Court  U.S. Supreme Court

U.S. Supreme Court