The Robin Hood Hills child-murder crime scene has grown incredibly cold in 13 years. Even the morbidly curious college students finally stopped haunting the drainage ditch behind the Blue Beacon Truck Wash in West Memphis, Arkansas, where 8-year-olds Christopher Byers, James Michael Moore, and Steven Branch were found killed and mutilated on May 5, 1993. “We tore that old place down,” says a Blue Beacon worker. He refuses to discuss the murders and won’t give me his name. “It’s over with, and I’m not allowed to talk about it. All these years later, I’m still trying to figure out if those three kids that got killed were the same kids we told not to play here that day because of the trucks.”

When I ask him if he believes they got the guys who did it, he hangs up.

The town has moved on. But questions about the murders and subsequent convictions of three West Memphis teenagers linger, many of them raised by two HBO documentaries, Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood  Deirdre O’Callaghan

Deirdre O’Callaghan

Damien Echols

Hills and Paradise Lost 2: Revelations.

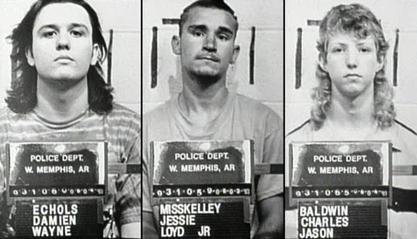

Paradise Lost documentarians Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky (who both also directed Metallica: Some Kind of Monster) first chronicled the 1994 Arkansas trials and subsequent convictions of three West Memphis teenagers — Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley — now known as the West Memphis Three. (Baldwin and Misskelley got life. Echols got the death penalty.)

The follow-up, Revelations, revisits West Memphis for Echols’ ill-fated state appeals and also highlights the earliest efforts of a now-worldwide network of WM3 supporters, led in the beginning by three Los Angeles advocates from the film industry: Kathy Bakken, Burk Sauls, and Grove Pashley.

And interest in the case is still growing. Sinofsky and Berlinger’s Paradise Lost 3 is slated for release sometime this year, and Dimension Films plans to release a film in 2007, which will be based on the book Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three by Arkansas-based investigative journalist Mara Leveritt.

Paradise Lost turned the West Memphis Three into icons. Supporters say it’s impossible to watch the documentary and miss the awful sense of American justice gone wrong, that the only crime the West Memphis Three ever committed was sticking out as black-clad outsiders in 1993 in a small Southern town.

“What struck me was that I kept thinking I was watching a movie with character actors,” recalls former Black Flag singer Henry Rollins. “The things the prosecution was saying, their witnesses, it was all so hopelessly stupid and sad. Justice got a black eye in those trials.”

Rollins is one of an ever-growing list of celebrity WM3 supporters that includes Johnny Depp, Eddie Vedder, Jello Biafra, Winona Ryder, Jack Black, Steve Earle, Trey Parker, and Metallica — to name a few — whose fund-raising efforts include concerts, art benefits, and compilation CDs. In 2002, Rollins released Rise Above, a CD of 24 Black Flag songs performed by various artists including Tom Araya (Slayer), Lemmy (Motörhead), Nick Oliveri (Queens of the Stone Age), Corey Taylor (Slipknot), and Ice-T, with all proceeds going to the West Memphis Three defense. The support Web site wm3.org, which is run out of Los Angeles, has received more than 3,485,769 visitors as of this writing.

Jason Baldwin

Today, West Memphis advertises itself as “a hometown feeling with big-city attractions,” a description you can read on the town’s chamber of commerce Web site or just glean by counting churches and ministries that line the residential streets. But West Memphis is also a known drug hub, where cops regularly seize illegal guns, pounds of marijuana, and kilos of cocaine at the West Memphis cargo inspection station, described by the National Drug Intelligence Center as one of the two busiest in the nation.

“I would characterize West Memphis as a place where a lot of folks travel through,” says spokesperson Steve Frazier of the FBI in Little Rock. “It’s a crossroads, a highly traveled city, and sometimes that brings the criminals who travel I-40.”

Jessie Misskelley

Yet, when the bludgeoned bodies of three small children were found in a drainage ditch behind the Blue Beacon Truck Wash, local police convinced the public that three impoverished local teens were good for the killing. This was accomplished with a stunning lack of evidence, the West Memphis Three advocates say. Moreover, it was accomplished within one day.

The sign of the cross

Christopher Byers, James Moore, and Steven Branch first went missing on the evening of May 5, 1993. According to John Mark Byers, the boy’s stepfather, Christopher had misbehaved at Weaver Elementary School and was sent home. “I spanked him three times with my belt with his pants up,” Byers recalls. And then he told the child not to leave the house. When Byers returned home at 6 p.m., Christopher was not there. Byers first told a cop that Christopher was missing at 6:30 that night and then was the first parent to report to the West Memphis police at around 8 p.m.

The children’s bodies were discovered in the ditch on the afternoon on May 6th. All three were naked and had received multiple head, limb, and torso injuries; they were hog-tied with shoelaces binding their wrists to their ankles. Steven Branch had bite marks on his face. It was determined that both James Moore and Steven Branch had drowned and suggested that Christopher Byers had drowned as well. Of the three, Christopher Byers had sustained the most violent injuries, including what appeared to be a sexual assault. He had a skull fracture at the base of his neck, stab wounds on his genitals; his penis was skinned and the killer had removed the child’s testes and scrotum.

One day later, the West Memphis Police Department had a motive — ritual child sacrifice, a profile of the killers, who they decided were probably members of a satanic cult — and three suspects: local heavy-metal fans Damien Echols (18), Jason Baldwin (16), and Jessie Misskelley (17). At noon on the following day, they visited the Broadway Trailer Park residence of Echols and began questioning him.

Jessie Misskelley has an IQ of 72, an indicator of mild mental retardation. On June 3rd, West Memphis police investigators questioned Misskelley about his role in the heinous crimes. The interrogation lasted 12 hours. Misskelley was never provided legal counsel or allowed to call his family. Only about the last hour of this was recorded, during which Misskelley confessed, implicating himself, Echols, and Baldwin in the murders.

The Misskelley statement was riddled with errors. He repeatedly got the timeline wrong. First he said the murders had occurred at 9 a.m., which would have been impossible as the children were all accounted for at school. Then he changed it to noon — also impossible.

Misskelley recanted his statement almost immediately, and his public defender, Dan Stidham, said that the only reason his client confessed was because he thought he could get the $50,000 reward. But within a day, the three teenagers were formally charged with murder.

Misskelley was tried and convicted in February 1994, but since he refused to testify against his friends, his statement was ruled inadmissible in the Baldwin/Echols trial. That commenced within the month, with Berlinger, Sinofsky, and the HBO cameras following every step of the way. “We thought we were going there to make a real-life River’s Edge and that these kids were guilty,” recalls Sinofsky. “We wanted to look into why they would commit such a heinous crime. When we realized they were innocent we went back to HBO and let them know it had gone in a different direction. We said we were kind of thinking the stepfather John Mark Byers did it. He was a fighting kind of guy, and one time he even said to us, ‘Just remember, boys, it all started here.'”

In March 1994, Echols and Baldwin were convicted of triple homicide. Echols was sentenced to death by lethal injection and is on death row at the Arkansas state penitentiary in Grady, where Misskelley is serving life plus 40 and Baldwin life without parole.

There was no weapon at the scene and no blood, other than what had collected when police removed the bodies from the water and placed them on the ground, leading to speculation that the murders were committed someplace else and the bodies dragged to the ditch. The state’s evidence that Echols was a Satanist amounted to an expert witness in the occult who had a mail-order degree and pentagrams Echols had scribbled in jail. The murder weapon was a clean knife that was found in a lake near Echols’ home, which resembled the knife that was possibly used at the crime.

Echols’ current attorney, noted San Francisco defense lawyer Dennis Riordan, was retained in 2004. He says: “The thing that led me to take this case was the startling sense that, in a death penalty case, there just wasn’t any credible evidence that connected him to the crime. You can read the Arkansas State Court opinion and they list everything that was offered against them, and it’s just terrifying that anyone could have been sentenced to death on any one of those six factors. A knife that was serrated? You could go into any home in Arkansas and find a serrated knife.”

According to FBI’s Frazier, who checked the old files, there was a request for an FBI profile on a probable killer — at first they were looking for a “Rambo” type — but it was not completed. “The West Memphis Police Department request for a profile was discontinued based on the fact that arrests had been made,” he says.

The devil wears Prada

Damien Echols wasn’t every teenager in America in 1993, but you could pretty much recognize the type. He dressed in black, wore skull earrings, and thought Guns N’ Roses singer Axl Rose was God. Some say he dabbled in the occult. And he was poor — there wasn’t always enough to eat. He lived in a shabby trailer park with a mom he loved and a stepfather he was ambivalent about. So he hung out with his friends, listening to heavy metal and reading Stephen King and Anne Rice. Sometimes they’d just sit by the lake all day and throw rocks at the water.

Echols was strange, but he didn’t have a history of violence; there was one brush with the law when he was 15, and he ran away with his girlfriend after her father discovered them having sex. He was then sent for treatment for a non-specific “psychotic disorder” at Charter Hospital. Echols was prescribed the usual antidepressants available at that time. By the time he was released, the conclusion by his doctors was that he was no longer depressed.

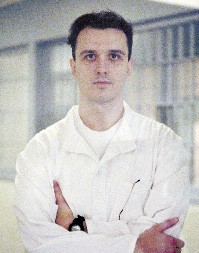

In his muck-gray and bulletproof glass visitors’ cell on death row, Echols (now 30) says, “If I had to do it all over again, I would not have stood out.”

Death row inmates are allowed a two-hour no-contact visit with the media. So Echols speaks through a vent in the wall. When wife Lorri Davis comes on Fridays, she is allowed one extra hour, and she gets to sit in the fishbowl with him.

He’s pale and anemic — he lives on a diet of Froot Loops and granola bars provided by Davis. In his prison whites he blends into the walls, except for his eyes, which are big brown sockets. He explains that he has arthritic hips from spending 13 years in a nine-by-nine-foot concrete cell, getting fed through a slit in the door. There have been an estimated 30 executions since he got here — many of the other inmates have become so desensitized to the process they don’t even look up from the television.

Attorneys have come and gone in 12 years — and there have been three failed appeals. Even though several jurors now admit to considering the inadmissible Misskelley statement, the appeals court ruled that it came too late, stating: “Echols’ claim of juror misconduct has been brought over a decade after his conviction. Clearly, this is a matter which could have been brought in a motion for new trial immediately after the verdict and conviction, but the argument is now untimely.”

Echols shakes his head: “Basically they are saying, ‘You didn’t file it on time so we’re going to kill you on a technicality.'”

There is no reason to expect a different Damien Echols from the one seen in Paradise Lost; after all, he went straight from that documentary to death row. Many of his supporters cite his intelligence and his outspokenness and that this is what they liked about him from day one. “I’ll tell you anything,” he says.

During his trial, his dismissive attitude and contemptuousness hurt him on the stand. When asked to explain the difference between Wicca and Satanism (so as to exonerate himself from charges that he worshipped the devil), his exasperated voice and facial demeanor indicated to the jury that this just wasn’t worth his time.

“I was in shock at my trial,” he explains. “When you’re innocent, you keep thinking surely somebody’s gonna realize something’s wrong and say, ‘This has gone on long enough.'”

In the late 1990s, Echols became a Buddhist, inspired by the teachings of another Arkansas death row inmate, Jusan Frankie Parker, who was executed in 1998. He meditates — sometimes as much as five hours a day — wrote his autobiography, Almost Home, Volume 1, and has had his poetry published in Porcupine, a literary arts magazine. He estimates he’s read 1,000 books.

“A huge deal for me is not even thinking about this place,” he says. “I read from the time I get up in the morning til the time I go to bed. My cell is nine-by-nine. There’s nowhere to look away.”

“Damien has done an amazing job of adapting to his environment and finding a way to deal with it,” Rollins observes. “He’s really impressive. If he could find a way to get it across, he could be a great teacher.”

So he reads catalogues and dreams about getting out — about wearing Prada ties and a nice Brooks Brothers suit, working in a bookstore, raising children, and voting in a presidential election. He dreams about the political impact he could have on this system one day.

“I was taught — and I believed — that our system worked; an innocent man couldn’t be convicted in America. I thought any moment now, I’m going home,” says Echols.

The family that stood by Echols during the trial has scattered. His mother calls maybe once a year; his dad remarried about six years ago and has a new family. His son’s mother, Domini, was around for two years after his incarceration and then married someone else. “People don’t stick around when you’re on death row,” Echols says. “In the beginning everyone rallies around you, but you can’t expect them to put their lives on hold just because yours is.”

Waiting for the DNA

Mostly now it’s just about his wife. Pretty and wholesome — with long brown hair, bangs, and a bike rack on her car — Lorri Davis’ sweet voice and demeanor suggest she hasn’t had a tough day in her life. Originally from Morgantown, West Virginia, Davis was living in New York and working as a landscape architect when she attended a screening in 1996 of Paradise Lost. It hit her about halfway through the film: “I was so horribly upset by it, and the next morning I woke up and thought, Oh my God, they didn’t do it. I never saw a movie and felt compelled to do something.”

She began writing Echols within a few days. One year later, she quit the New York job — “Rue the day,” she says — and moved to Little Rock, where she gets to spend three hours every Friday visiting her husband in prison. She brings him the granola bars, strokes the fund-raising machine, shuttles supporters back and forth from the airport, packs Echols’ 26 boxes of books, types his manuscripts, or sends a book he picked out to a stranger who took the time to write.

One could easily conclude that Davis is crazy. Even Stidham recalls thinking as much when he learned that Davis had married Echols. “Naturally, I made that assumption,” he says. “But she’s just a decent human being. And once you meet her, you realize she’s very intelligent and sane. I admire and respect her.”

Decent, sane, and tenacious: Last year, right before she hired Dennis Riordan, she got the cell phone numbers of several noted defense attorneys. She called and begged them until they finally asked her to stop.

“When I first moved here, I would go to court hearings and sit way in the back,” she says. “I didn’t want anyone to know who I was. When we got married, I thought, I’m married to this person and I’ve got this role.”

“In the beginning, I was not convinced,” Davis’ mom, Lynn, remembers. “I said, ‘Should he get out, I wonder if he rolls over in bed and says, “Lorri, I did it. I beat the system.”‘ But we met with Damien about four times, and the first time I asked him. I said, ‘Damien, did you do it?’ And he said, ‘I did not.’ And I felt it. I just knew that he couldn’t do that to those little boys. I know that every little town has its problems, and they pinpointed Damien and his buddies because he was a thorn in their side.”

With nearly every state appeal exhausted, Echols hopes to be headed for federal court, but Misskelley and Baldwin still have pending state appeals. All three are waiting for the results of DNA testing. (Baldwin and Misskelley declined through their attorneys to be interviewed for this article.)

Tragedy makes a reality star

John Mark Byers stands by the coffee machine in the Parkway convenience store in Millington, Tennessee. He listens, visibly bored, to another man’s story about being wrongfully arrested for a car theft. By anyone’s standards, this isn’t the most interesting tale, but to John Mark Byers, stepfather star of the two Paradise Lost HBO documentaries, it’s gotta sound dull as dirt. So when the man finally works around to the part where he gets his car out of the police impound, Byers interrupts. “Do you recognize me?” he asks, impatiently.

The man shakes his head slowly. “I’ve seen you,” he says. Clearly, he has not.

“Were you in this area in ’93?”

He was.

“Do you remember the three 8-year-olds that were murdered in West Memphis? One of those three 8-year-olds was my son. Do you remember seeing me in the media?”

The man registers shock, but he nods politely. Uh-huh, maybe …

“That’s it,” Byers says, satisfied. “People ask me for my autograph all the time,” he tells me later. “There wouldn’t even have been a Paradise Lost 2 if it wasn’t for me.”

He repeats it a couple of times during our two-hour breakfast at the convenience store, where we chow down on eggs, bacon, biscuits, and grits. “You don’t know what these are,” he says, pointing to the plate heaped with grits. He’s gracious, but it’s a challenge: A New York liberal — which he believes me to be — doesn’t eat grits, and John Mark Byers doesn’t like New Yorkers.

A lot of people don’t understand Byers, including a lot of big-city folk who believe the WM3 were victims of “hillbilly justice.” He reserves special venom for the producers of Paradise Lost.

“Two Jew-boys from New York City took advantage of our families in this crisis to make money,” he says.

Still, he’s gracious. His new wife, Jackie, is a lovely person. They buy me breakfast and Byers helps me off with my jacket. He’s currently working as a house painter.

Believing in the guilt of the West Memphis Three and resentful of the documentaries that stirred up questions about their innocence, the parents of James Moore and Steven Branch have mostly avoided the press. Byers, on the other hand, made quite an impression in Paradise Lost: In one scene he was ranting and raving about the details of the crime. In another he curses the men who killed his babies. He gave the HBO producers a knife, which turned out to have his and Christopher’s blood on it. Additionally, it turns out that Byers was working for the police as a drug informant. His antics made such an impression on the HBO producers that, halfway through the filming of Paradise Lost, they began to believe that he might have been the killer. Byers has a long history of drug and alcohol abuse and was drunk throughout the making of both films.

“I wasn’t in my right mind,” he admits. “I tried to stay on medicine and marijuana, and they [Sinofsky and Berlinger] capitalized on that. They set me up to look like the fool.”

In July 1994, Byers was arrested for contributing to the delinquency of a minor for allegedly instigating a knife fight between two youngsters. That same month, he was arrested for burglary. During that summer, neighbors filed restraining orders against Byers for allegedly whipping their sons with the metal handle of a flyswatter and firing shots at their home. Byers was on probation when he was arrested for selling Xanax to a narc in 1999. He served 18 months. His ex-wife, Melissa, who was highly visible during Paradise, had a longstanding heroin problem. She died of undetermined causes on March 29, 1996.

Byers made Jackie watch the documentaries the first week they met. “I watched them and I was like, dang,” says Jackie Byers. “My major in college was psychology. I’m a pretty good judge of character, and if I thought for one second he did something terrible in his life I wouldn’t have married him.”

WM3 supporters have tried to connect Byers to the murders, but they’ve turned up very little in the way of hard evidence. His recollections of the crime include some inaccuracies: He claims the WM3 flunked lie detector tests when there is no evidence to support this; he claims Echols had driven by his house a few months before the murders when Echols never had a driver’s license and had never driven a car.

Misskelley’s lawyer, Stidham, says the case is confused because Byers and Echols both act strange: “[Echols] was a kid and not sophisticated enough to understand how he came off. And Byers still doesn’t understand how his antics made him look guilty.”

Byers regrets that he didn’t get more money for appearing in the documentaries and swears he’s not going to do another. A few minutes later, he corrects this. He might, if he has a contract and a lawyer by his side.

At the end of our interview, he asks me, “Now that you’ve met me and I’ve answered every question, do you think I’m the kind of guy who could have done such an awful thing?”

Decades of research by the FBI and hundreds of millions of dollars committed to investigating the “phenomenon” of satanic murders have not turned up a single example of a ritual child-killing in this country by any religious group — including “Satanists” — in the last century. As of this writing, Damien Echols has been on death row 4,796 days.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles CityBeat.

Deirdre O’Callaghan

Deirdre O’Callaghan