If you enjoy any sort of music or news that’s slightly off the beaten path, you may ultimately have a bit of Scotch tape to thank for its availability on the radio. Back in 1967, when President Lyndon Johnson was about to sign the Public Broadcasting Act into law, the language was being debated up to the last minute, including the use of the word “radio.” In Listener Supported: The Culture and History of Public Radio, author Jack Mitchell describes how the words “and radio” had been removed from the document only days before heading to Johnson’s desk. At the last minute, the bill’s author used tape to add the two words back in, thus laying the foundation for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, including National Public Radio and its nearly 50-year legacy of local affiliates.

Not long after that, in the mid-1970s, there was an explosion of independent, listener-supported community stations. And since then, public (NPR-affiliated) and community (volunteer) radio stations have offered the best alternatives to commercial music and news radio. For all the touting of “choices” offered by market-driven institutions, commercial broadcasting can take on a dispiriting sameness. As brilliant as pop culture may be at times, let’s face it: A city’s creative life depends on art that rises above the demographic- and market-driven ethos of commercial media.

Memphis might have been very different if nonprofit radio had not taken root here. But take root it did, and now the city boasts four non-commercial stations that are driven and supported by their listeners. April is an especially auspicious time to honor that legacy, it being the month when two of our most venerable stations were founded. Here’s a look at the state of non-commercial Memphis radio today.

WKNO (91.1 FM): The Mother of Mid-South Public Radio

“In April of next year, the station’s going to be 50 years old,” says Darel Snodgrass, director of radio at WKNO-FM. “We went on in April of ’72, which was only like three months after NPR was formed. The only program they had was All Things Considered, so all the rest of the time was filled with classical music.”

As Snodgrass points out, that twin commitment to both news and music has defined WKNO ever since. “There are not many stations that do what we do anymore, that have programming that mixes news and classical music. Most stations have added HD channels and split it, with all news on one and all classical on the other. There are only about five or six stations in the country that do what we do, and mix them. It makes us kind of unique.”

Though one might imagine that a kind of homogeneity pervades NPR stations across the country, there’s actually a lot of diversity among them. For one, stations differ radically in the degree to which they weave local news into the content of national programs. Snodgrass is justifiably proud of WKNO’s commitment to Mid-South news. “Doing local news is hard. It’s a lot of work, and we’ve got people now who do wonderful work. That’s one of the things I’ve been so pleased with over the last 10 years: the growth in our local news reporting.”

But it’s no surprise that the onetime music major and current music host is even more proud of the station’s commitment to his preferred art. As he explains, it is not just music in the abstract, but music as curated by devoted DJs in real time.

“This [NPR] station is unique in that we individually program our own shows. We pick our own music. This just doesn’t happen anymore. Even other classical music stations have a program director who’s telling them what to play. And of course commercial stations are all heavily programmed, mostly from New York and Los Angeles. So Kacky [Walton] and I consider ourselves to be extremely lucky. We can use that freedom to respond to things. If it’s a gloomy, rainy day, we can play something uplifting.We can react to things both locally and nationally, which a lot of people just don’t get to do. It’s kind of amazing, honestly.”

Kacky Walton, the station’s music coordinator and other music host, agrees. “You can respond to events,” she says. “The best example was after September 11, 2001. We just had news for I don’t know how many days. But when we finally went back to music, there was still that feeling of sadness, and you had to be really mindful of playing something with the appropriate mood to it. It was difficult, but at the same time, I discovered a lot of music that I hadn’t really played before.”

This was especially true as the lockdown conditions of the pandemic set in last year. Radio took on a new importance in people’s lives. “In hard times, radio gives you a sense of community,” Snodgrass says. “We heard a lot from folks who were listening to a lot of classical music. They may have previously been going to their jobs every day. Now they’re at home, listening to classical music, because it’s a haven, it’s a refuge. It provides a sense of security and continuity. These are pieces that have been around, in some cases, for hundreds of years. And they’re still there.”

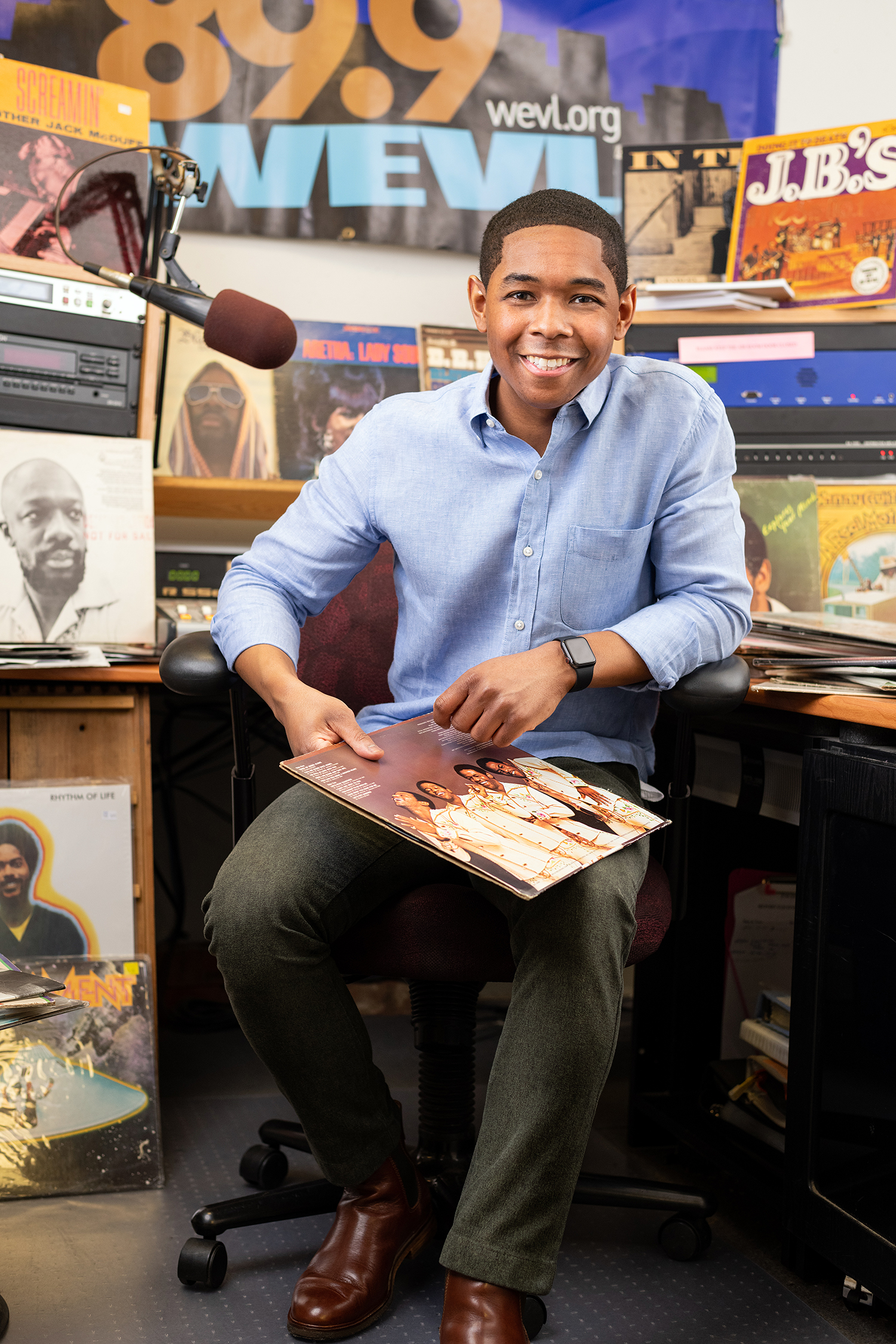

(Photo: Antwoine McClellan | AJM Images)

WEVL (89.9 FM): The Pioneer Spirit

WKNO was one of the first affiliates to join the NPR family, benefiting from the largess of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, but not long after its launch, there arose an alternative take on nonprofit radio in the heart of Midtown. In fact, for many years, it was only in Midtown, because the station’s 10-watt broadcast couldn’t reach any farther.

“I think I came to the station in 1978, two years after it went on the air,” recalls Judy Dorsey, the longtime station manager for WEVL. “I was strictly a volunteer. I was just interested in it. I’d read about it in the paper and couldn’t believe we had something like this in Memphis. Granted, it was only 10 watts. You could only hear it in certain areas of Midtown. But just the fact that it was there and people were doing this was very exciting to me. And when I first went down to the house where it was located, I knew, ‘Here’s my people. I found ’em.’”

That esprit de corps fueled much of the counterculture, of course, including the little station that could. “There were a lot of what you might call hippies and assorted musicians. They were drawn to it almost immediately. And curious people like me, people who liked oddball music that wasn’t being heard.” As with the hippies that started the Memphis Country Blues Festival, there was an inclusiveness to the WEVL volunteers’ ethos that lent itself to diversity.

(Photo: Karen Pulfer Focht)

“I remember the first time I heard a live performance on the air,” Dorsey recalls. “I think it was [local blues legends] the Fieldstones. They played live on there several times, because we had connections with them. And they had what they called a Blues-a-thon. And I remember opening the door and there was Rufus Thomas up at the top of the stairs, doing the Funky Chicken!

“That was the first night that Dee ‘Cap’n Pete’ Henderson ever came to the station. He lived way over in Box Town, and had gone to Radio Shack and bought a big ol’ antenna, and stuck it up on his roof, just so he could hear the Blues-a-thon, because he’d read about it in The Commercial Appeal. Then he called the DJ on the air and the guy told him, ‘Come on down here! You know more about this stuff than I do!’ So he came down.” That encounter led to the late Cap’n Pete becoming one of the station’s preeminent blues DJs, whose shows are still rebroadcast to this day.

Homemade antennas and chance encounters capture the spirit of WEVL well, which has become a local institution on the strength of its do-it-yourself attitude. It persisted even as the station outgrew its original wattage in 1986. “Our first transmitter building, when we went back on the air in ’86, was all built with donated materials and volunteer labor. I don’t think we paid for anything out there,” says Dorsey.

The same personal commitment, and reliance on local pledges, has helped WEVL weather the cycles of funding and attrition. The Carter years were a good time to begin. “You had a lot of little 10-watt stations starting up at the same time as WEVL. A lot of them were born in that part of the 1970s. We’re charter members of the National Federation of Community Broadcasters — we were some of the first people to join it. Our first station manager and program director were getting paid through grant money from the federal government, and when the grant money ran out, that’s when they left. There were all kinds of different grants in those days. When all that stopped, that was a bad time. It was Reagan, he ruined everything. That was sort of a dark era, because we didn’t have any money to pay anybody. There was a period where it was strictly volunteers. It was a bit chaotic.”

But sometimes you can make chaos work for you, as WEVL’s longevity bears out. Today, they carry on much as before, still using the homemade record shelves made years ago, the epitome of listener-supported radio, with last year’s mid-pandemic pledge drive being one of the station’s most successful ever.

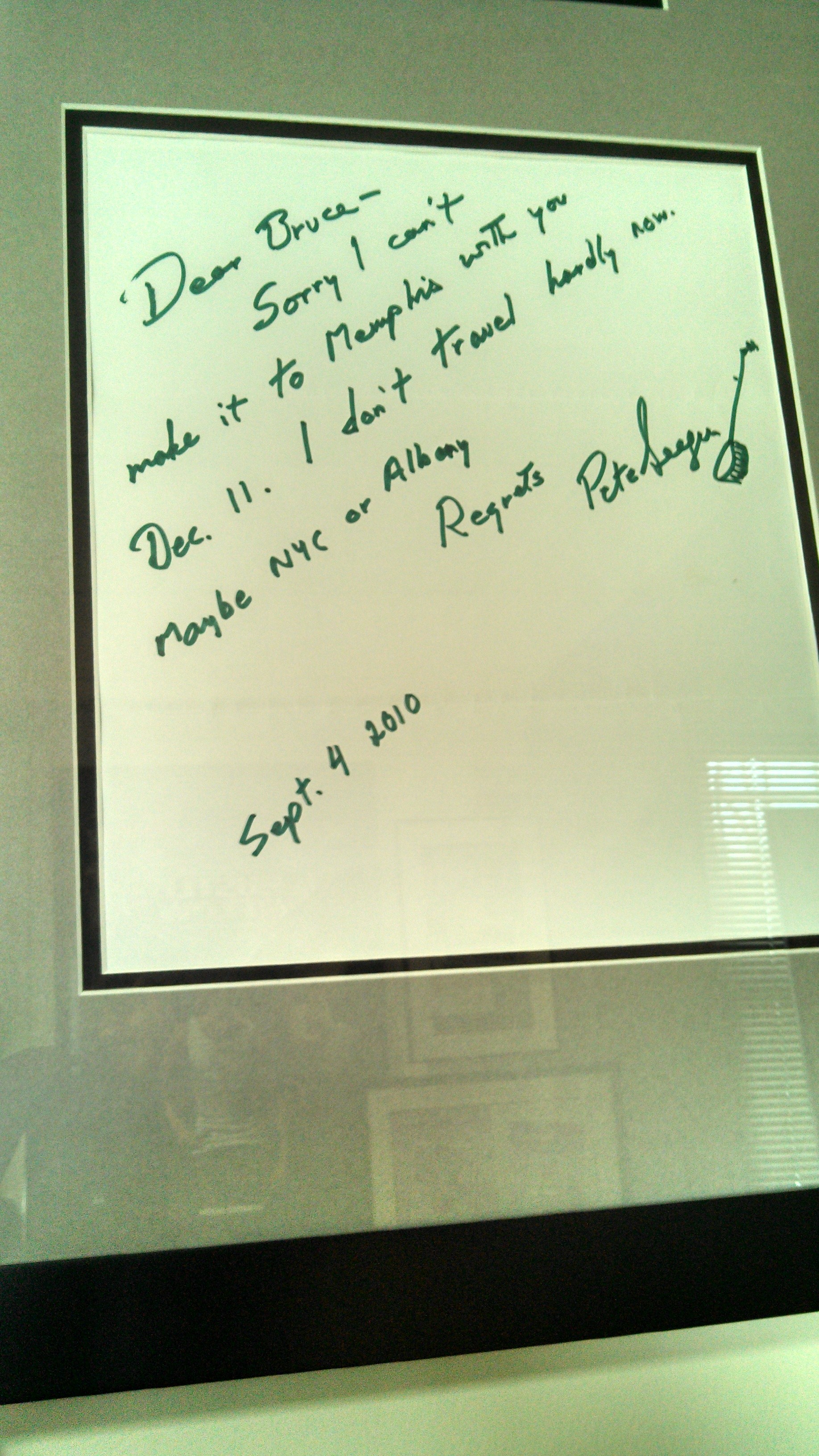

(Photo: Courtesy of Tommy Warren)

WYPL (89.3): Serving the Underserved, Dishing Out Memphis Magic

Though WEVL’s original 10 watts may have been rather weak, a station now using one of the region’s most powerful transmitters had even more humble beginnings. “We are now a 100,000-watt station, covering a 75-mile radius from the tower in West Memphis. That tower was actually donated to the library in 1997, and its power and size is a bit of overkill, but that’s the situation we’re in.” So reflects Tommy Warren, broadcast manager for WYPL, the station based in the basement of the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library.

Yet the station still retains its original mission of offering the vision-impaired and others readings of current newspapers, magazines, and books — one of only two such stations in the country. “It started out in 1978 as a ham radio kind of situation,” says Warren. “I am only the second radio manager here since then. Before me, there was a manager who was himself vision-impaired. He organized volunteers, and they’d sit in a little booth and read, and you had to have a ham radio at home to pick it up. It operated like that for about 15 years.”

When Warren came on board, he added an element to the readings by tapping into the huge digital archive of Memphis music in the library system. That has seen its audience increase dramatically, especially overseas, where the station can be heard online.

“We started doing all the music shows five or six years ago. Now we’re bringing in DJs like Randy Haspel and Lahna Deering and Barbara Blue. People who actually play Memphis music also come in here and produce shows.”

The new emphasis on music has made WYPL a real player on the community radio scene, although they, unlike the other stations mentioned here, do not depend on public donations. “Because we’re paid for by the city of Memphis, we feel there’s an obligation that we have to live up to. Especially through COVID. When there are emergencies, people turn to over-the-air radio for their first source of information.”

(Photo: Jamie Harmon)

WYXR (91.7 FM): The New Kids on the Block

Yet another player in the nonprofit world of the airwaves arrived right in the middle of the pandemic lockdown last year, but the timing does not appear to have slowed its roll. Its frequency was already familiar to Memphians, having been where the University of Memphis’ station, WUMR, had lived on the dial for decades. But sometime in 2019, the U of M decided the jazz-only format and station management needed a change of course.

Robby Grant, executive director of WYXR, describes the process as an evolution of goals. “The University of Memphis knew they wanted to do something different with the radio station. They had an existing relationship with the Daily Memphian, and reached out to them, but the folks at the Daily Memphian said, ‘We don’t want to run an entire radio station.’ So they approached the Crosstown Concourse. The U of M wanted to get more connected with the community, so this was another way for them to reach outside of their campus. It made sense for it to be a partnership.”

For Grant, who has a background in software and web development, a crucial element was also making the most of digital technology to archive every show put on the air, which community stations in other cities have implemented. But once that infrastructure was in place, the shows themselves had to be created. (Including Flyer Radio, a show produced by Flyer staff featuring news, interviews, and Memphis music, and airing every Friday at noon.)

“They brought me in,” he says, “and I brought in Jay B [program director Jared Boyd] soon thereafter to really shape the programming. I had some ideas. I knew free-form radio allows a lot of flexibility for the community to be involved. I wanted some talk programming. I felt like that was missing. There’s some talk programming on a national level, but I thought there was a way to elevate more of the community talk. The Daily Memphian has their news part of it. So I was working on the nuts and bolts, bringing that together, getting agreements in place. When Jay B came on, we hit the ground running with the programming. We built on our networks, along with the applications process, to find DJs.”

By the time of their debut broadcast on October 5th of last year, they had 70 volunteer DJs, arguably with a greater programming diversity than any other station in the country. But it felt a bit like a minefield. As Boyd explains, “Frankly, moving from WUMR’s jazz-lover focus to a new format, a free-form radio station, was going to be a hard change for a lot of people, no matter what our content was. We were taking something away from the community that was extremely needed, in some people’s eyes. And that can be rough.”

Nonetheless, Boyd was determined to raise the stakes of the diverse programming. “People may not expect to hear community radio in Memphis, in the South, that has a space for hip-hop, house music, or punk. But the reality of Memphis is that those people are as much if not more representative of our community than the genres most people think of when they consider community radio. So how and why could we be representative of the community if we’re not representative of those people?

“And there are still places where we haven’t been able to find the right person, who understands what we do, and can present to their segment of the community. Like the Latinx community. But also the Vietnamese community and the Chinese and Japanese and Ethiopian and Somalian and Kenyan communities. There’s tons of cultures who pair their origins with the identity of being American and being a Memphian. But there are only 24 hours in a day, so we have to be creative about how to bring everybody on.”

Though there are more ambitious plans ahead, Boyd feels that the mix WYXR has settled on passes one key test, perhaps the toughest test of all: “The feedback we’ve been getting is that people don’t know how to explain what we do, except that it just feels and sounds like Memphis,” he says. “I wanted to lead with that.”

Editor’s Note: This month, WKNO, WEVL, and WYXR all have their seasonal pledge drives. We urge you to tune in and give generously.

Bruce Newman

Bruce Newman