Students at Memphis’ Whitehaven High School got a chance last month to hear from journalists Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa, authors of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book on George Floyd — his life, his brutal killing by police in 2020, and its aftermath.

But the students didn’t get to hear any excerpts from His Name Is George Floyd, and they weren’t allowed to take home copies of the book from school. The authors had to give their presentation without going too deep into the book’s main theme of systemic racism.

Who determined the restrictions and why is unclear. The organizers of the event, a local partnership called Memphis Reads, said their instructions to the authors were based on guidance from the school district on complying with Tennessee law that requires that books used in school be “age appropriate.”

Memphis-Shelby County Schools officials disputed their account, but repeatedly declined to answer questions about what they told the organizers or how they interpreted the law. In an email to the authors after the event, district communications chief Cathryn Stout said MSCS did not run the book through its review process before the visit.

In the end, the authors told Chalkbeat, the students who gathered at Whitehaven that day were shortchanged by restricted access to the book and a censored experience.

“Neither Tolu nor I know who to cast blame on,” Samuels said. “I’m not sure we could, or we should.”

But the ambiguous restrictions in this and other Tennessee laws have caused concern at the local level about compliance, Samuels said, resulting in “messy, potentially explosive debates between entities that usually get along.”

Floyd was killed during an arrest in May 2020, when a Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee onto Floyd’s neck for several minutes. An onlooker’s video recording of the event went public, triggering a huge outcry and calls for and policing reform. The officer was ultimately convicted of second-degree murder.

Samuels and Olonnuripa’s book, written while both were reporters at the Washington Post, looks not just at the incident but also at how pervasive racism in education, criminal justice, housing, and health care systems shaped Floyd’s life. “We learned about the man himself … and much more than how he died,” Samuels said during a forum at Rhodes College.

They also wrote about what happened afterward: a season of demonstrations, dialogue, and unrest during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by what they call a “burgeoning backlash” to the racial justice movement, resulting in state laws across the country that stifled classroom discussions on race.

Tennessee was among the first states to legislate what public school students can — and cannot — be taught about race, gender, and bias. And the penalties are steep. Educators who violate the law may have their teaching licenses suspended or revoked. Districts can be fined for repeat offenses.

MSCS officials and the Memphis Reads organizers did not specifically cite this law as a factor in what ultimately happened at Whitehaven, but the law nonetheless hangs over educators’ decisions about what topics are appropriate for classroom discussion. Two Memphis teachers are among five in Tennessee challenging the law in federal court.

Tennessee’s Age Appropriate Materials Act, meanwhile, requires schools to publish a list of what’s in their library collections online and develop policies to review and remove books that aren’t appropriate — a term that the law leaves undefined.

MSCS has leeway to interpret this law, but longstanding tensions between the majority-Black, Democratic-led city and the mostly white, GOP-dominated state government mean the district can ill afford to risk a fight with the state over the nuances of race and books.

Christian Brothers University runs the Memphis Reads program in partnership with other community groups. In communication with Chalkbeat, CBU cited the Age Appropriate Materials law as the reason it understood that books and materials couldn’t be distributed at the Whitehaven event and said that the guidance came from the Memphis school district.

CBU and other Memphis Reads partners “were under the instruction of MSCS leadership when completing the formatting and regulations concerning the Age-Appropriate Materials Act,” Justin Brooks, the CBU community engagement director who heads Memphis Reads, wrote in an email to Chalkbeat.

MSCS officials wouldn’t confirm that to Chalkbeat, or explain whether Tennessee’s law regulating classroom conversations about race influenced any restrictions.

In the email to the authors after the event, shared later with Chalkbeat, Stout wrote that time constraints prevented the district from going through its own process to approve the book. Stout wrote that the district regretted that their “experience was anything less than welcoming.”

“Given the new, more detailed process, it will take some time to coordinate, but please know that ‘His Name Is George Floyd’ is now under consideration to be added to the Whitehaven High School library collection,” Stout wrote to the authors, “and we look forward to having conversations with other school communities as requests arise.”

Separately, Stout shared with Chalkbeat a copy of a description from library book distributor Baker & Taylor that categorizes the book as “adult” and among the American Library Association’s “Notable Books for Adults.”

Stout also wrote in a public social media comment explaining the district’s position that the American Library Association labeled His Name is George Floyd as “adult literature (18 and older).”

ALA spokesperson Raymond Garcia told Chalkbeat that the group “does not rate books” for age appropriateness.

Booklist, a book review magazine published by the ALA — and listed among resources for librarians in an MSCS manual — uses its “adult” label not to be restrictive but to signal that a book would be of interest primarily to adults, Garcia said.

His Name is George Floyd is also categorized as “nonfiction” and “social sciences.”

If the label was a factor in the decision not to allow Memphis Reads to distribute the books at Whitehaven, then that’s an “inaccurate understanding” of the purpose of such book labels, said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom at the American Library Association.

“We can think of any kinds of works of literature that would have been originally rated as of interest to an adult reader that are absolutely fine for young people to read, and it’s not too controversial,” Caldwell-Stone told Chalkbeat, citing “To Kill a Mockingbird” as an example.

Nonetheless, the ambiguity in Tennessee’s standard of “appropriateness” creates gray areas and heightens the stakes for local districts concerned about avoiding a violation, Caldwell-Stone said.

If a person or district cannot risk breaking the law, “then you’re going to be very thoughtful about what books you offer,” she said, “and thereby limit the opportunities to learn and engage with all kinds of ideas, even controversial or difficult ideas.”

A spokesperson for the Tennessee Department of Education says MSCS did not reach out to the state for guidance, and MSCS didn’t respond to a question from Chalkbeat about that issue.

Thanks to a donation from the publisher, Viking Books, students who want a free copy of the book will be able to get one from Respect the Haven, a community development group in Whitehaven that’s part of Memphis Reads.

Whitehaven High School serves some 1,500 students and is known among Memphis for its school pride and focus on students’ post-secondary scholarship achievements. Almost all of its students are Black, and about half of them are from low-income families.

“This event basically got censored out of fear of violating some law,” said Jason Sharif, head of Respect the Haven. “With us being a predominantly Black city, a predominantly Black school district, you cannot keep books like this or stories like this from being told to Black students.”

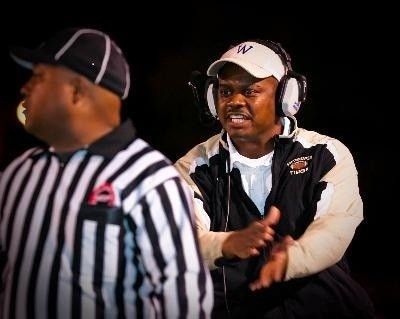

By the time Samuels and Olorunnipa arrived at Whitehaven High School for the event on Oct. 26, they knew some of the restrictions they would have to operate under. The two reporters were prepared to tell students about the journalistic work that went into writing the book, but to avoid going into depth about many of the issues it raised.

Brooks, from Memphis Reads, had told them they wouldn’t be able to read directly from the book, or talk about the book’s discussion of how systemic racism created many barriers for Floyd, long before his arrest and killing. MSCS was involved in setting these restrictions, Brooks said. The district did not comment on its role.

Instead of an open question-and-answer period, five students were pre-selected to ask Samuels and Olorunnipa prepared questions, which was different from the open conversations at the two other panels that Memphis Reads organized. This was in line with MSCS protocol for events, Brooks said.

Brooks said it was CBU’s call to keep the event closed to media, out of concern for student safety. A Chalkbeat reporter attended two similar events at the college level.

Stout said Brooks and Sharif had created a narrative about the event that is “inconsistent” with the district’s point of view and its own initiatives. She highlighted a Memphis school integration curriculum and a social emotional learning curriculum involving the death of Tyre Nichols, a Black man who was fatally injured by Memphis police after a traffic stop in early 2023.

MSCS told Chalkbeat that it was glad Whitehaven students had the opportunity to hear the journalists speak, as did CBU in its own communication.

And Samuels and Olorunnipa, who had early doubts about being part of an event with restrictions on their speech, said they were grateful for the opportunity, too. They were approached at the end of the event by a Whitehaven high schooler with a notebook full of questions who said he wanted to be a journalist. The authors relished the chance to expand what the student imagined for his future.

“Even through this period of backlash, we think it’s important to continue to push forward and continue to make a pathway for people who are caught up in the back and forth,” Olorunnipa said during another forum.

“A lot of these kids have nothing to do with the politics,” Olorunnipa added. “They are just trying to make it. They’re just trying to live their best lives. And sometimes they become pawns in our political fights.”

Laura Testino covers Memphis-Shelby County Schools for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Reach Laura at LTestino@chalkbeat.org.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.

Clement Santi

Clement Santi  Clement Santi

Clement Santi  Clement Santi

Clement Santi