After it was discovered that the RiverBeat Music Festival‘s social media accounts posted a clumsily-Photoshopped image that inflated the apparent crowd size (which the festival organizers copped to, blaming the photographer and removing the image), many in the online-iverse ramped up their complaints about the festival, dissing the lineup, the attendance, and even the lack of chain link fencing along the river shore (believe it or not).

Yet, as a musician, a music fan, and journalist embedded in the actual RiverBeat experience, I witnessed throngs of happy listeners and had more than a few magical encounters myself. In the end, that’s what will stay with us. Here, then, are a few personal, highly subjective moments that make a celebration of music on this scale worth the while, complemented by the Memphis Flyer‘s own mixtape.

Charlie Musselwhite

The magic began before I even entered the festival gates. Walking along the perimeter toward the entrance, I heard the sound of pure liquid gold ringing out over the river. It was the blues harp of Charlie Musselwhite, known as “Memphis Charlie” in his youth, his family having moved here from Mississippi when he was a toddler, though he was based in Chicago as his career accelerated in the ’60s. To this day, he’s criminally under-booked in Memphis venues, making this moment a rare one indeed. This octogenarian and the melodic flow of his harp are national treasures.

Lucky 7 Brass Band

Seeing this group in the charged setting of the festival brought home what a tremendous font of creativity and groove the Lucky 7 can be. As I walked into Tom Lee Park, I heard the familiar strains of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” but far groovier and brassier than the original. It was quickly followed by Rage Against the Machine’s “Killing in the Name,” Victor Sawyer’s singing full of the original’s fury, but layered over the forward momentum of a second line groove. An utter revelation.

DJ’s at Whateverland

The Memphis gem Qemist took DJing to new artistic heights, weaving together disparate tracks into a whole greater than the sum of its parts. “It’s about to get real Black real fast!” he announced at one point. The crowd gathered in the shade of the fanciful tent shimmied and swayed along with him…even the staff walking past. “I see you, Security! Get your strut on!” he exclaimed. On Saturday, WYXR’s Jared Boyd, aka Jay B, aka Bizzle Bluebland kept up a similar vibe with some fine disco-tinged vibes, puffing on a jumbo cigar as he manned the wheels of steel.

Durand Jones & the Indications

I’d never heard this old school soul and R&B vocalist live, but certainly will again after the scorching set he delivered last Friday afternoon. The very on-point band formed over a decade ago at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, but a distinctly more Southern flavor of soul springs from Jones’ roots in Hillaryville, Louisiana. “I feel like I’m an ambassador of the rural South,” he quipped at one point. “I’m just a boy from a town of about 500 people, and our land is being taken away from us. It’s about time we saw what is going down.” Midway through their cover of Irma Thomas’ “Ruler of My Heart,” Jones spoke wistfully about a young man who came to Memphis “with just a guitar” and made Thomas’ song his own, bringing the house down with Otis Redding’s version, “Pain in My Heart.”

Talibah Safiya

We just profiled this neo-soul/hip hop auteur, and, armed with fresh new tracks from her new album and a tight live band featuring MadameFraankie on guitar, she held the Stringbend Stage last Friday with aplomb. Even in the group’s tight execution of beats there was a playful looseness, exemplified when, seeing a few sprinkles in the air, they launched into an impromptu take on “I Can’t Stand the Rain.” That soon gave way to more of Safiya’s originals. “Look to your right,” the singer called out to the audience, pointing to the Mississippi River. “Let’s honor that body of water,” she said, and then launched into perhaps her most popular track, “Healing Creek.”

Take Me to the River

Having written about the group assembled by Boo Mitchell in last week’s cover story, I knew this would be a special moment, but it exceeded all expectations. Lina Beach, the young guitarist for Hi Rhythm, rocked her originals with verve, Jerome Chism delivered soul standards like “Tryin’ to Live My Life Without You” with passion, and Eric Gales delivered some scorching guitar work that was both virtuosic and soulful on “I’ll Play the Blues for You.”

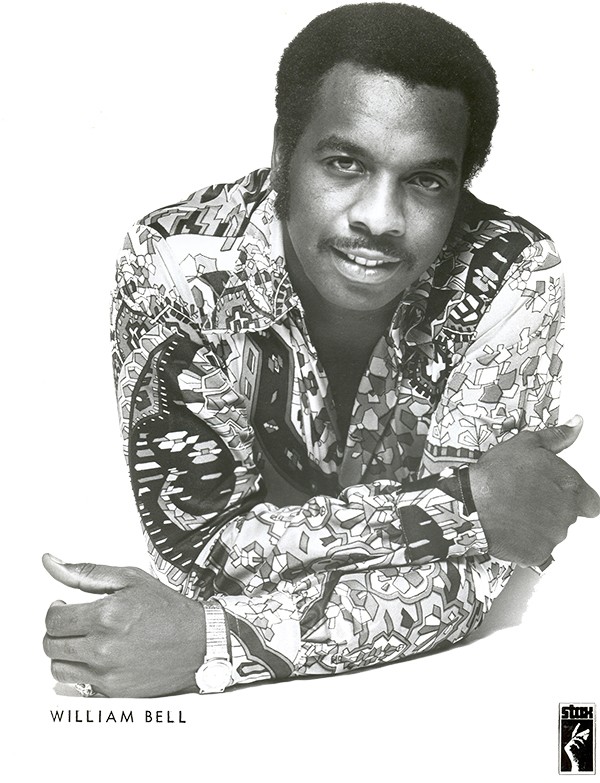

While Mitchell is naturally grounded in Royal Studios and Hi Records, that latter song’s provenance in the Stax catalog confirmed that Hi Rhythm was the perfect vehicle for all stripes of Memphis soul. That was especially clear when Carla Thomas took the stage, cradling a crutch in her right hand but looking spry as she exhorted the crowd to do some classic straight-eighth note “soul clapping” while the band vamped on the intro to “B-A-B-Y.” She followed that up with the song her father Rufus put on the charts, “Walking the Dog,” whereupon Chism appeared with a small pup wearing ear protectors. That in turn was followed by the inimitable William Bell delivering stone classics like “I Forgot to Be Your Lover,” making the Take Me to the River set a festival highlight.

No Blues Tent, Plenty of Blues

As if to make up for the lack of a blues tent, always a fixture at Beale Street Music Festivals, the blues seemed to crop up everywhere at RiverBeat. Kenny Brown brought the Hill Country Sound on day one, laconic and completely at ease as he unleashed guitar licks with his trio. On Sunday, the Wilkins Sisters brought their unique gospel-blues straight out of Como, Mississippi, just as their late father, Rev. John Wilkins, and their grandfather, Rev. Robert Wilkins, did before them. As lead singer Tangela Longstreet said, “We lost our daddy in 2020. But I can still hear him telling me, ‘Don’t stop singing, baby!'”

And there was more of that sanctified blend from Robert Randolph & the Family Band, as the master of sacred steel guitar delivered a sermon from the church of good times. In his hands, the pedal steel guitar became an engine of squeaks, squalls, and heavily distorted riffs. Indeed, their finale of “It Don’t Matter” was the weekend’s personal highlight of unfettered abandon, and, judging from the way Boo Mitchell and Lina Beach were dancing, they felt the same. Such high energy blues were also apparent in Southern Avenue‘s fiery set, wherein the humble acoustic guitar played by Ori Naftaly on most of the tunes presented country blues riffs amped into overdrive, adding a new grit to their sound.

Yet there were blues in more unexpected niches. Lawrence Matthews‘ latest work draws heavily on sampled blues in the Fat Possum Records catalog, and his anti-hype attitude, sitting calmly on a stool as he delivered his rhymes was only underscored by the bare-bones country blues guitar underpinning much of his work. Al Kapone has also taken to blending his hip hop vision with the blues, and that was on full display in his Saturday set, especially on the dread-laden “Til Ya Dead and Gone (Keep Movin’).”

And finally, bringing it back full circle to classic soul revivalism , there was plenty of blues in a groovy set by Rodd Bland and the Members Only Band, the horn section’s evocation of his father Bobby “Blue” Bland’s classic take on the minor-key “St. James Infirmary” giving this listener chills. Some of those same great horn players appeared with the Bo-Keys as they backed up singers Emma Wilson and John Németh in a stomping soul set. Are players like Jim Spake, Marc Franklin, Kirk Smothers, Tom Clary, and Tom Link becoming the new de facto Memphis horns? Their presence on the RiverBeat stages, and so many records cut here, suggests as much.

Memphis is a Star

Perhaps the most striking pattern of the weekend was the way that the biggest stars of the event expressed their gratitude for playing our city. Of course, that was to be expected of Memphis-based mega stars like 8Ball & MJG, who made their set ultra-topical when they announced, “We’re going to dedicate this to the mayor!” then launched into their hit, “Mr. Big” in honor of Mayor Paul Young. Fellow hip hop star Killer Mike also got very specific in his love of the Bluff City, paying homage to both Gangsta Boo and Jerry Lawler in one breath.

There were plenty more tips of the hat to our city. Black Pumas singer Eric Burton called out the city many times, but his greatest tribute was perhaps through his vocal style, which one friend described as “Al Green without the horns.” Their psychedelic soul fit the riverfront crowd like a glove.

The Fugees‘ electrifying set also embraced our city in very musical ways. The crowd went mad as Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean (sans Pras) performed “Zealots,” with its distinctive sample of The Flamingos’ “I Only Have Eyes For You,” but no one could have expected them to shift that beat into a shuffle for a lengthy bridge, wherein their crack ensemble sounded like nothing so much as a consummate Beale Street blues band. Aside from the mere fact of their appearance at the festival, quite a coup for RiverBeat’s organizers, they showed their love of Memphis in myriad small ways, as when Hill sang “killing me softly in Memphis,” or turned the line “embarrassed by the crowd” into “embarrassed by Memphis’ crowd.” Naturally, the crowd ate it up.

And yet, fittingly, the most involved embrace of the Bluff City came from Tennessee native Jelly Roll, who closed out the weekend just before Sunday’s second downpour descended. As the set was still warming up, the Antioch, Tennessee native shouted, “It feels so good to be back in my home state!” Later, he quipped “Since we’re in one of the birthplaces of rock and roll, I figured we’d play a little rock and roll,” before launching into “Dead ManWalking.”

But then he got more personal. “When I was growing up, my family would drive down to for Memphis in May, to be right here in front of this river,” he said. “I feel like this is God’s exact fingerprint on the bible belt, right here.” He noted his disbelief at now being on the festival stage where his musical heroes once played, then added, “I cant express how honored I am that you people are out there standing in the fucking rain for this!”

Then he began to reminisce: “When I was 13, we were all listening to rap. I’d go up to my brother’s room, looking for whatever smelled like skunk. And someone gave me a mixtape from Memphis, Tennessee labelled Three 6 Mafia.” As the night wore on, he displayed his formidable rapping chops, even calling out his old friend in attendance, Memphis rapper Lil Wyte. It peaked when he described his influences as “somewhere between Hank [Williams] and Three 6 [Mafia],” then launched into his mega-hit, “Dirty South.” The multiracial crowd went wild in the drizzle, celebrating the hybrid confluence of the many musical styles that typify Tennessee, Memphis, and the RiverBeat Festival itself.

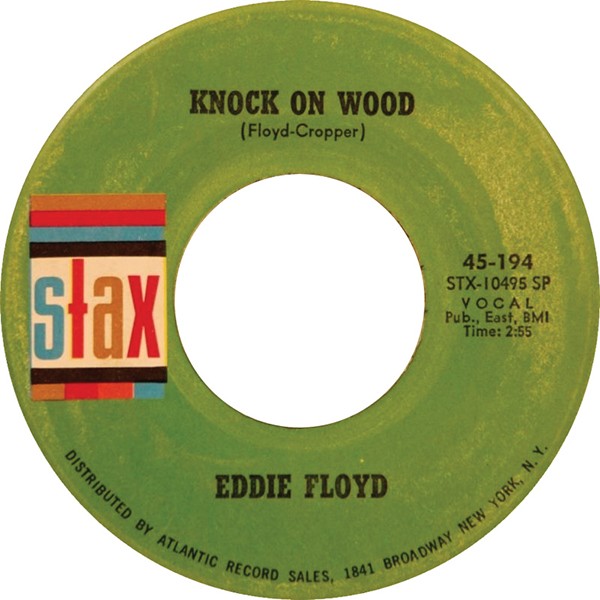

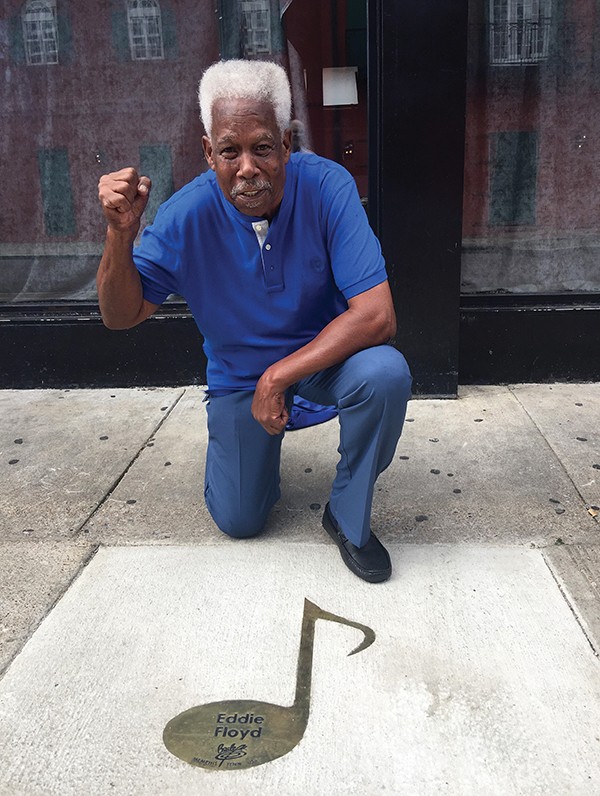

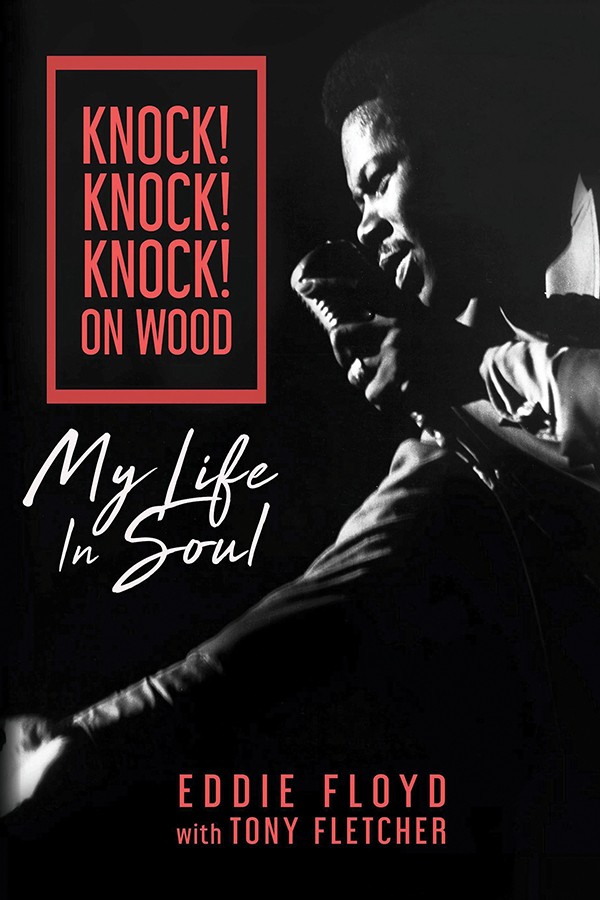

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd  David McLister

David McLister  Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Minus Red Productions/Candied Yam Music

Minus Red Productions/Candied Yam Music

Jonny Pineda

Jonny Pineda

Chris Paul Thompson

Chris Paul Thompson  Matt White

Matt White  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Catherine Elizabeth

Catherine Elizabeth  Kyel Dean Reinford

Kyel Dean Reinford  Josiah Roberto

Josiah Roberto  David McClister

David McClister  Ronnie Booze

Ronnie Booze  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Focht

Focht  Alex Burden

Alex Burden