Raised By Sound Fest, the music festival and fundraiser staged by community radio station WYXR and Mempho Presents, is once again in the offing, scheduled to have the Crosstown Concourse bursting with sound this Saturday, December 7th, and, as with the event’s previous iterations, the mix of performers is intriguingly eclectic.

Through its short history, Raised By Sound has earned a reputation for drawing top-tier artists for its main concert event, always held in the Crosstown Theater, and this year is no different. In 2022, when Jody Stephens’ reconstituted Big Star quintet planned only a few shows in honor of #1 Record, the Raised By Sound Fest was a pivotal performance for them. And last year, Cat Power made Memphis one of their first stops when they began touring their Dylan tribute album, The 1966 Royal Albert Hall Concert.

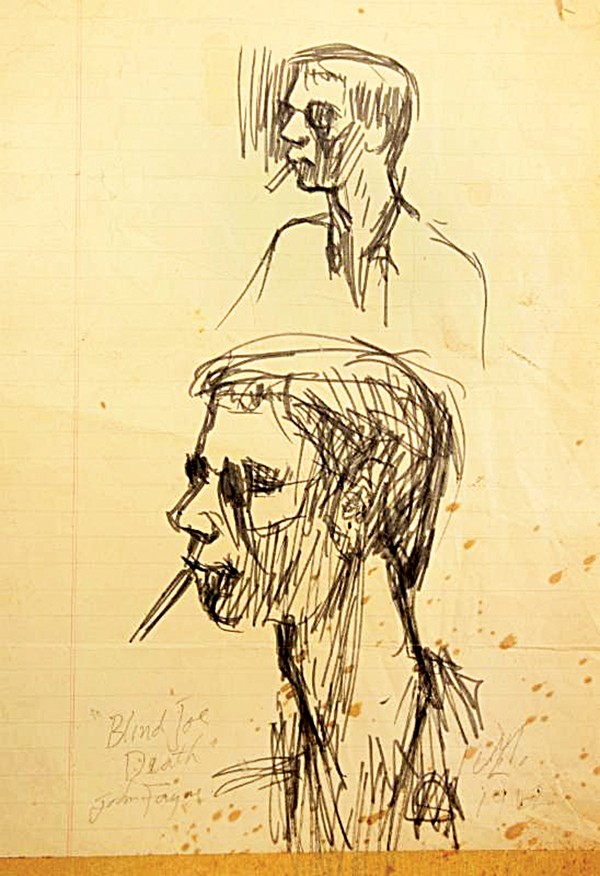

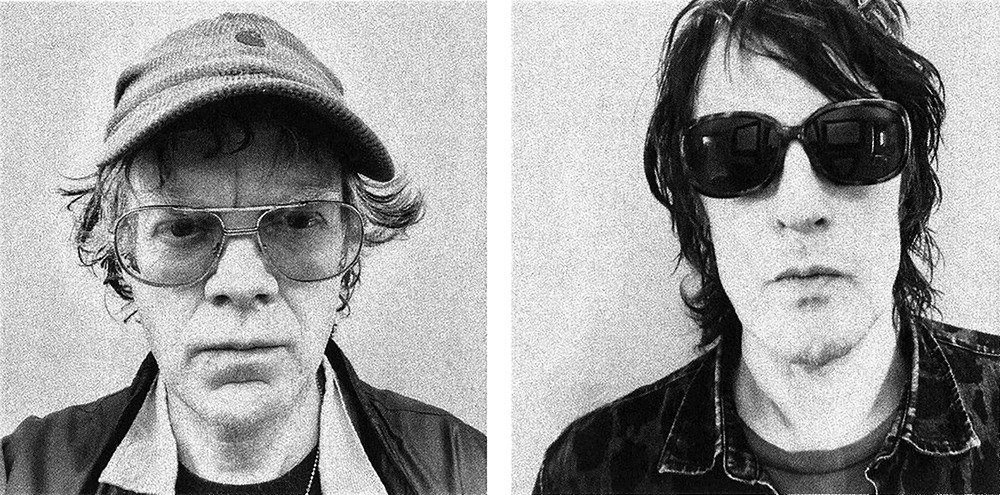

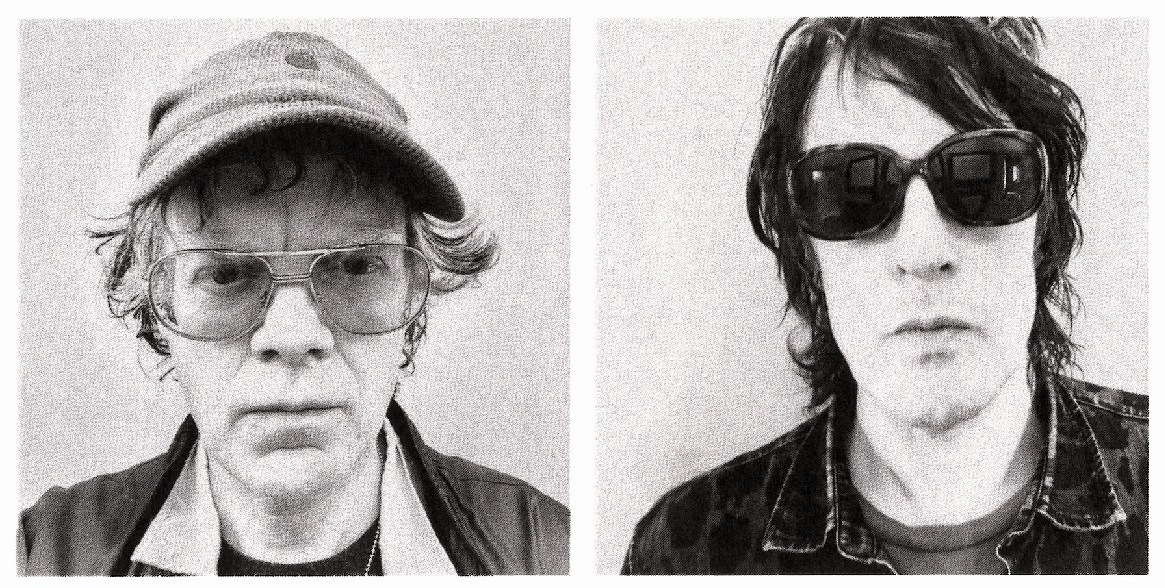

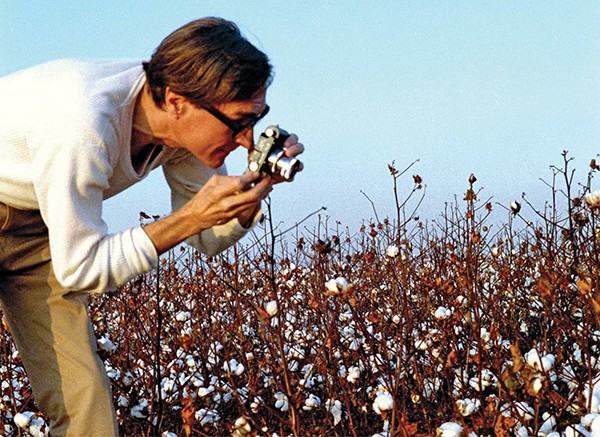

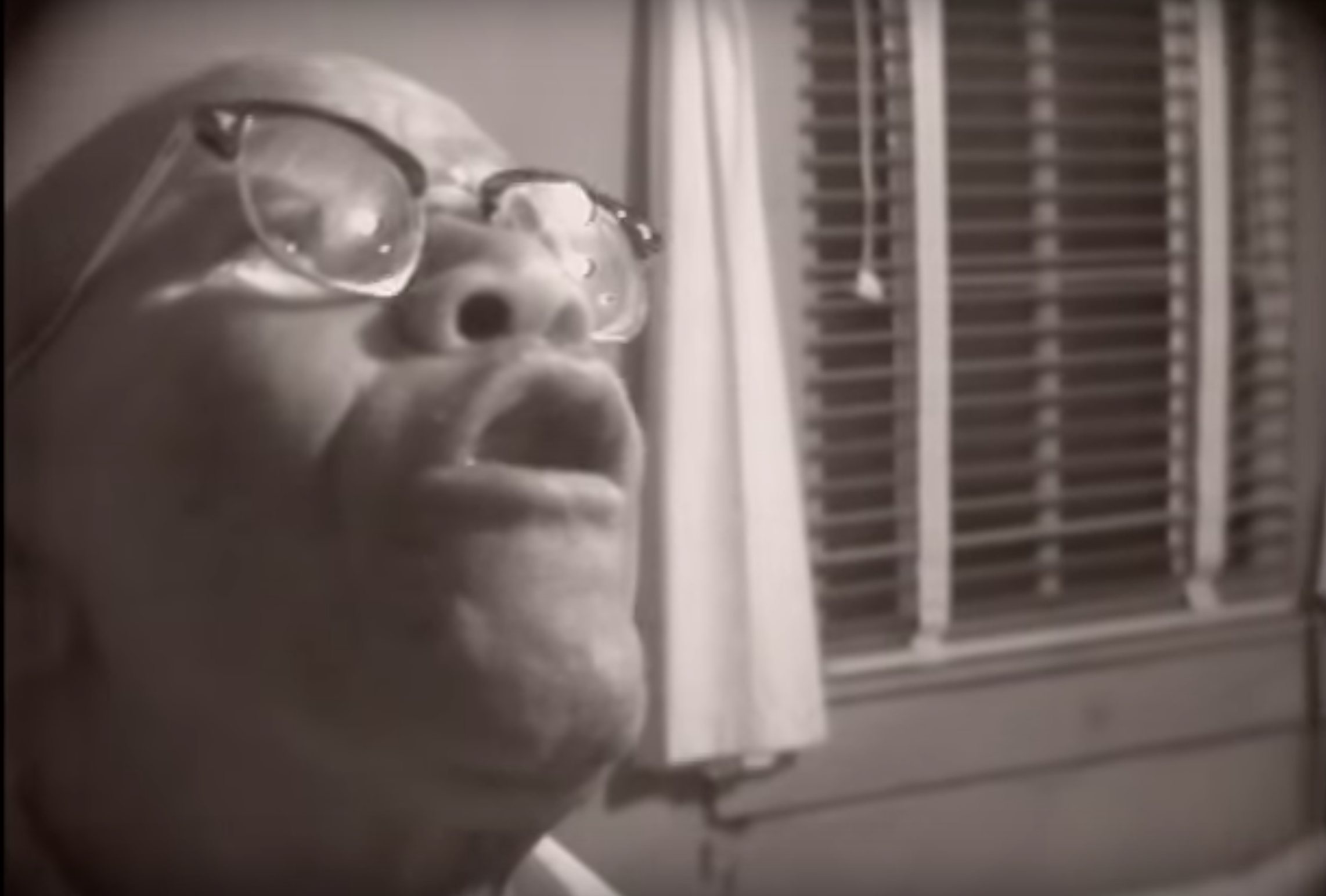

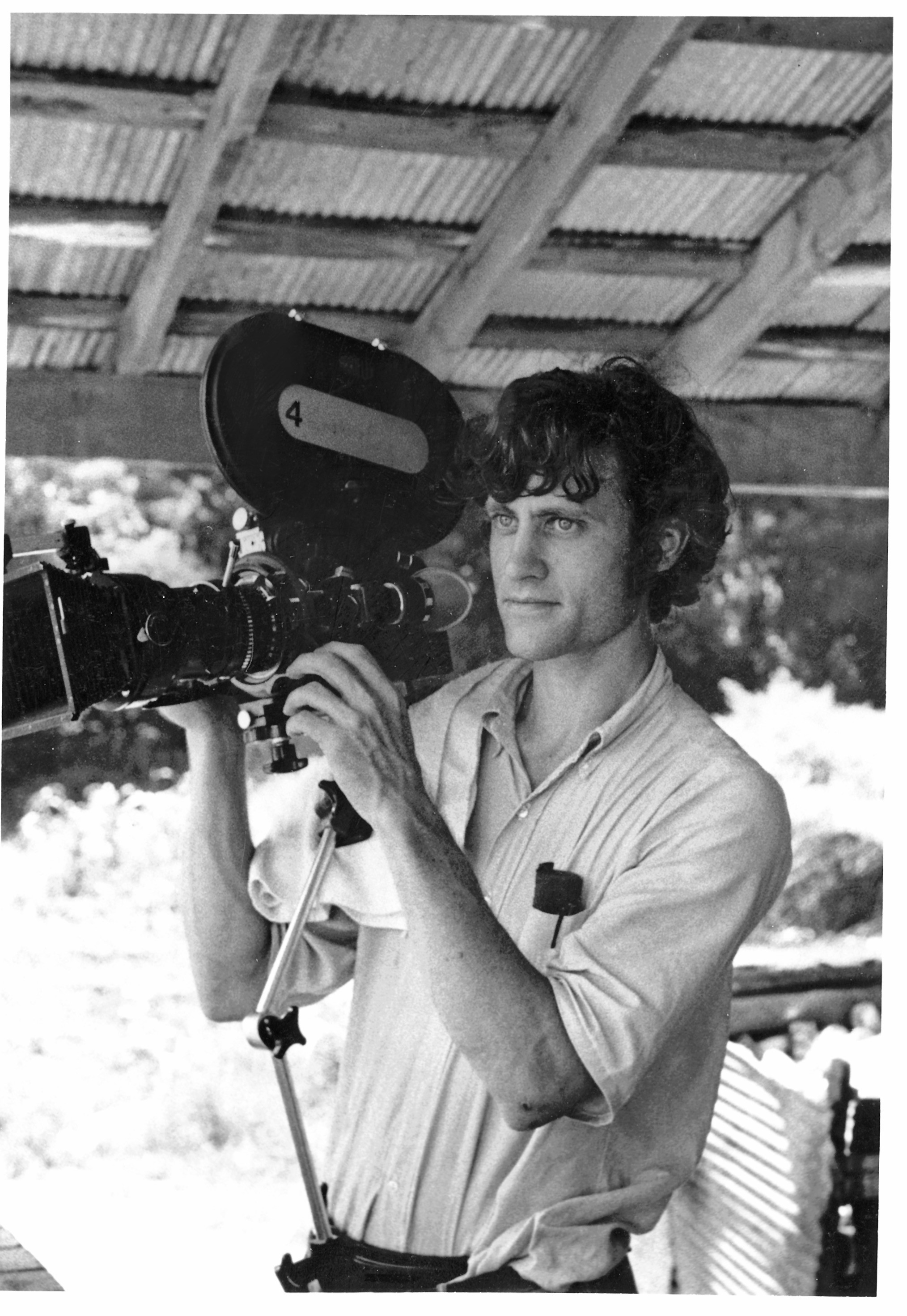

This year, WYXR has outdone itself once again for Raised By Sound’s main concert, presenting a live score to the William Eggleston film, Stranded in Canton, performed by J Spaceman and John Coxon of Spiritualized. “We just heard they had a really incredible show in London,” says the station’s executive director Robby Grant, “and in the U.S., Memphis is the only city they’re doing it in, outside of New York and L.A.”

As Grant notes, these marquee events all came together by way of the station’s openness and centrality as a meeting place for creatives of all kinds. “We keep our antenna up,” he says. “We have a huge window. We’re very welcoming. We’re very transparent. There’s a lot of benefit to that and making these connections.” The Spiritualized event is a case in point, as WYXR DJ David Swider, owner of Oxford’s The End of All Music record store, told Grant that the group’s live score was slated to be released on the Fat Possum label; the next day, Winston Eggleston (son of the photographer/filmmaker) mentioned that the group had reached out to him about permission to use the film. Things simply clicked by virtue of the station’s network.

Yet that capstone event, now sold out, is only one of many musical experiences that Raised By Sound will offer. Throughout the day, many other performances will echo in the columns of the Central Atrium, and that will only heat up once the final credits roll for Stranded in Canton, as the ticketed after-party kicks off in the East Atrium at the top of the red staircase, with a DJ set by Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney of the Black Keys and performances by hip-hop legends Tommy Wright III and Lil Noid.

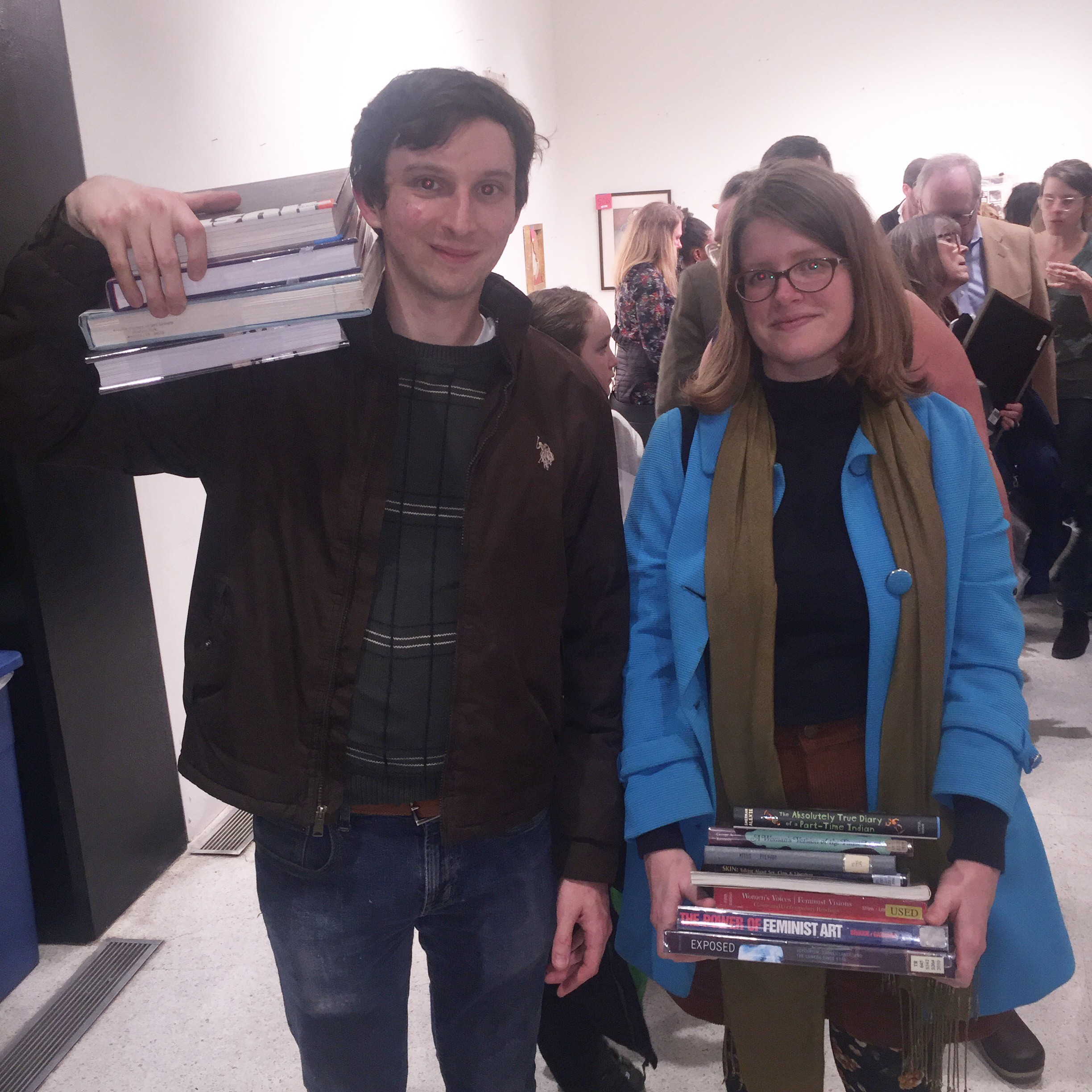

The free music begins at 1 p.m., when artists from the University of Memphis’ Blue T.O.M. Records will perform, including Meaghan Christina, Ozioma, and Canale. “It means a lot to us to be able to give [Blue T.O.M. artists] that level of exposure,” says WYXR’s program manager Jared Boyd, “and we’re also promoting an educational component, partnering with Grammy U, Stax Music Academy, and Crosstown High School. It creates a level ground for them to be on the same bill as the Black Keys and Spiritualized. It’s bringing it all under one house.”

That revue will be followed by Fosterfalls, a solo performer also based in Memphis. “They’re a really interesting solo artist,” says Grant. “They’re kind of acoustic, very ethereal, with a lot of loopy-type stuff, and they’re a great example of a local artist who’s getting out there and working really hard and just doing it.” Also in the hard-working vein is the blues-rock HeartBreak Hill Trio, fronted by Matt Hill, a longtime presence on the Memphis scene, known for his axe work with wife Nikki Hill. Once the trio has livened things up, Brooklynite Max Clarke, aka Cut Worms, will take the stage. His 2019 album Nobody Lives Here Anymore was produced by Matt Ross-Spang. And finally, the afternoon will close out with a solo show by Hurray for the Riff Raff’s Alynda Segarra, who has close ties to New Orleans despite being from the Bronx.

Indeed, all of the artists happen to have ties to Memphis. Celebrated Memphis-born photographer Tommy Kha, for example, has worked closely with Hurray for the Riff Raff. Yet the festival organizers are not strict about that as a criterion for inclusion. As Boyd notes, “We wanted to be able to present homegrown artists as well as artists who have some sort of significant Memphis or regional influence. Some are from elsewhere, but were called to Memphis because of music.”

“You don’t have to be a Memphis-connected artist to be booked for Raised By Sound Fest,” adds Grant, “but we found that every artist we booked has some connection. Like, no matter who we book, because Memphis is such a music city, there’s some connection.” That even goes for the performers from Spiritualized, who first debuted their live score for Eggleston’s film a decade ago at the Barbican Gallery in London, as part of Doug Aitken’s Station to Station festival. Now, a recording of that has been released by the local heroes at Fat Possum.

The after-party, too, will have strong Memphis roots. The Black Keys, based in Nashville, are not only steeped in the North Mississippi blues via that same record label, but have worked closely with Memphis’ Greg Cartwright. And, of course, Tommy Wright III and Lil Noid were on the ground floor of the local hip-hop revolution that gave rise to superstars like Three 6 Mafia. Wright is arguably the better known of the two, his music having been embraced by the skateboard scene. As Boyd notes, “There’s even a skateboard hardware company in L.A. called Shake Junt, and their entire brand image is an homage to Memphis rap culture!” But Lil Noid’s profile is also rising, and, tying it all together, he’s even featured on a new Black Keys track, “Candy and Her Friends.”

All told, the Raised By Sound Festival will provide a compelling glimpse and staggering diversity of music in Memphis, but other dimensions of the city will be represented as well. Community groups like Music Export Memphis, Memphis Music Initiative, and CHOICES will have tables, and visual artists like Sara Moseley, Darlene Newman, and Toonky Berry will have works either on display or being created as the music plays on. It’s all part of a concentrated celebration of what Memphis brings to the world. As Boyd says, “We have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to talent. And if you grew up in it, you may not always realize that most places are not like this.”

Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  MIchael Donahue

MIchael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  MIchael Donahue

MIchael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  MIchael Donahue

MIchael Donahue  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Winston Eggleston

Winston Eggleston  © Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust © Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust © Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust © Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust © Eggleston Artistic Trust

© Eggleston Artistic Trust Koto Bolofo

Koto Bolofo  © Jennifer Steinkamp

© Jennifer Steinkamp

Alex Greene

Alex Greene