Many who lived in Memphis during the ’90s and early aughts know Bill Ellis’ name — he was the music writer at The Commercial Appeal for nearly a decade, and his byline appeared in the paper for even longer. “I have to pinch myself that I was in Memphis when I was,” he says, thinking back on those days. “Jim Dickinson and Sam Phillips and Isaac Hayes were just a phone call away. I still can’t believe I was there at that time. The music I covered in the ’90s — the emerging hip-hop scene and also the North Mississippi hill country blues — those things resonate to this day. When I left, I realized that they were important, and time has only proven that in my mind.”

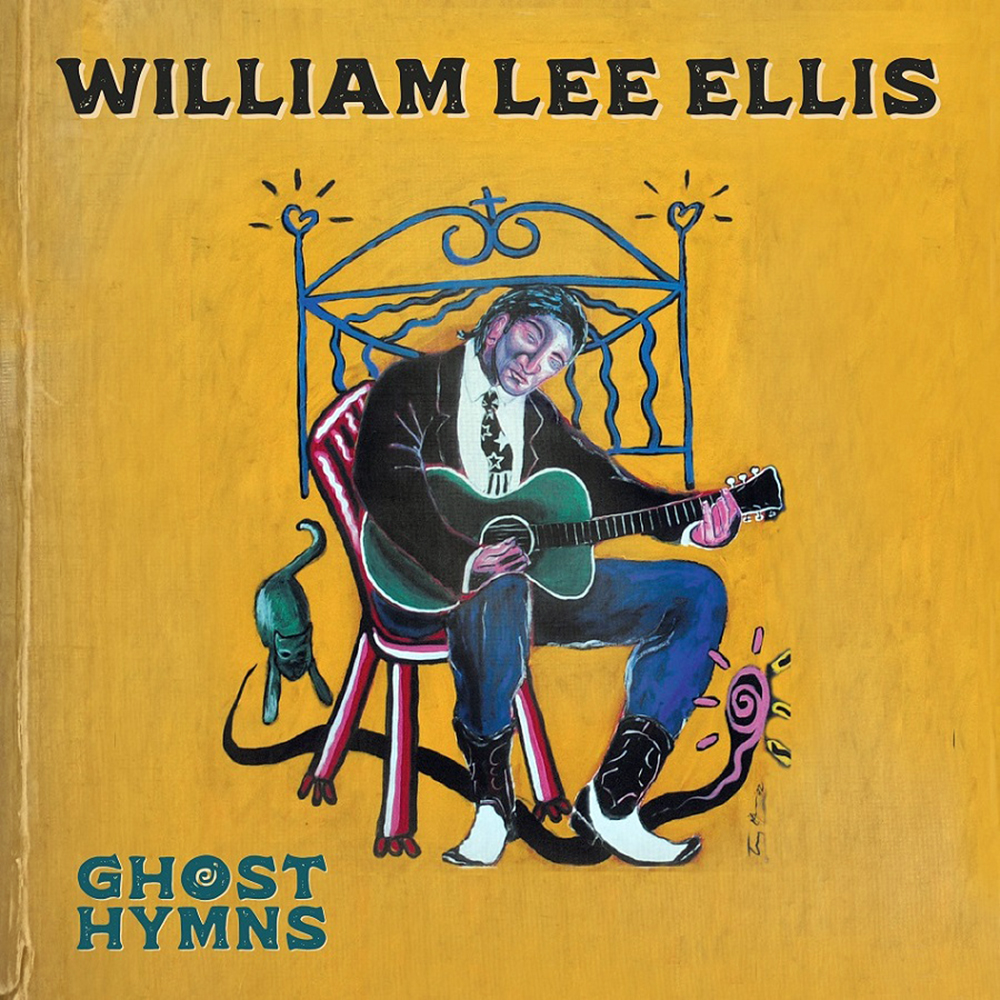

Meanwhile, he was pursuing another track as William Lee Ellis, the name under which he releases his folk- and blues-influenced music, a side of him that’s being foregrounded anew with the release of his sixth album, Ghost Hymns (Yellow Dog Records). Yet while his first release came out in 1999, during his tenure as a music writer, he’d been performing since long before that. Indeed, his father, banjoist Tony Ellis, is a veteran of Bill Monroe’s early-’60s Blue Grass Boys. But Bill Ellis didn’t quite follow in his father’s footsteps. After frequently backing the elder Ellis on guitar during his teen years, he studied classical guitar at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

It took an encounter with one of Memphis’ great traditional blues and ragtime guitarists, Andy Cohen, to steer him beyond both classical and bluegrass. “I met Andy through my dad back in the late ’80s,” says Ellis. “He gave me a pile of records and said, ‘Here, learn these.’ Six months later I showed up and I’m playing all the songs on those records.” Moving to Memphis in the ’90s only sealed his love of the blues.

In fact, he ended up putting journalism on the back burner in 2005 to study ethnomusicology with David Evans, ultimately writing his doctoral dissertation on the Reverend Gary Davis. That in turn led him to a faculty position at Saint Michael’s College in Vermont, where he’s currently chair of fine arts and associate professor of music. But Memphis still figures heavily in both his scholarship and his music. As for the former, one need look no further than the current exhibit he curated for the Art Museum of the University of Memphis, “Build Me a Heaven of My Own: African American Vernacular Art and the Blues.”

As for the latter, Ghost Hymns is bursting with Memphis influences and talent. On one track, Cohen plays dolceola, a kind of keyboard-enhanced zither; another tune was written with fellow former music writer Larry Nager, who also co-produced the album; and Memphian Brooke Barnett designed the cover.

Beyond those contributions, and the influence of Memphis on Ellis’ general aesthetic, the album sports more global influences, reflecting the artist’s lifelong peregrinations. “It’s not a world music record,” says Ellis, “but it is a record with some interesting global touches to it, by virtue of the people I call friends in Burlington, if that makes any sense.” The album’s Bandcamp notes are more specific: “Played on an array of instruments from fretless banjo and slide guitar to Ghanaian percussion and Chinese yueqin, the original tunes of Ghost Hymns offer an expansive view of tradition, visiting blues, gospel, high life, and more in a singular journey.”

While most of the songs were penned by Ellis, the echoes of world folk traditions are unmistakable here, from album opener “Cony Catch the Sun,” where Ellis’ fretless banjo recalls Taj Mahal’s work with Malian kora master Toumani Diabaté, to Matt LaRocca’s lush string arrangement for “Earth and the Winding Sheet,” reminiscent of British art-folk artist Nick Drake.

Yet Ellis points out that the album’s greatest influence was closer to home: his own father. One of Tony Ellis’ originals is on the album, and his presence is felt throughout. “Looking back,” says the younger Ellis, “there are guiding voices in the wilderness helping you figure out who you are as a musician. My dad, first and foremost, being that. I hear more of my dad on this album than on any of my other records.”