There are 11 names on the October 3rd ballot for Memphis mayor, but that well-watched race is generally thought of as coming down to only three of those names — incumbent Mayor Jim Strickland, former Mayor Willie Herenton, and current County Commissioner Tami Sawyer. A fourth candidate, Lemichael Wilson, maintains that he has enough support to be considered viable, as well.

Of the presumed top three, one, Herenton, has a past record to be judged by; another, Strickland, has a current record subject to voter reckoning; and the third, Sawyer, offers a platform strongly animated by promises of progressive reform. Beyond that, there has been little opportunity to make comparative judgments about the three, inasmuch as there has been no public debate or candidate forum featuring all three.

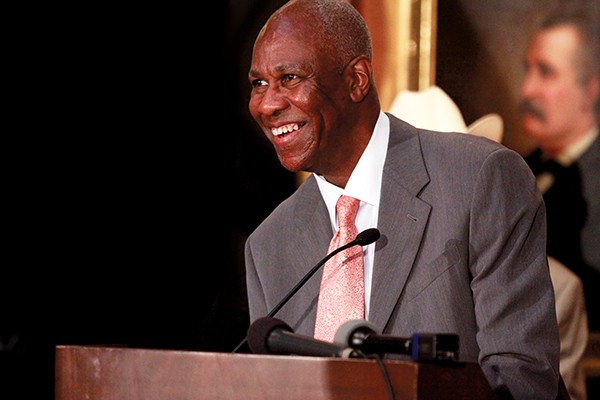

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

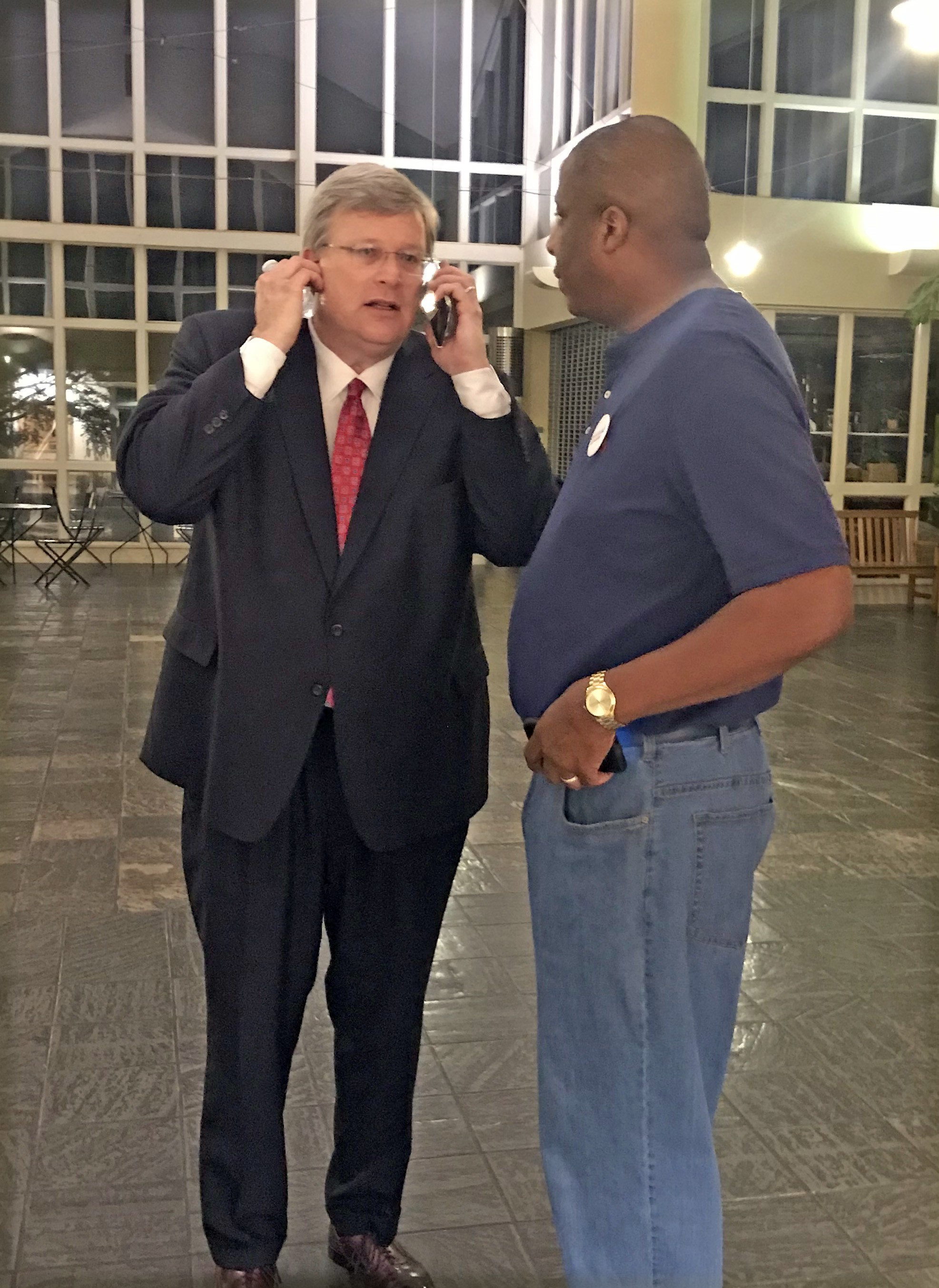

Incumbent Mayor Jim Strickland

There have been all kinds of claims and reasons put forth to account for that circumstance, but the root facts are these: Herenton has opposed all efforts to include him in such a mutual confrontation, and Strickland has declined any joint endeavor that excludes the former mayor. For her part, Sawyer has accepted a series of open invitations that both Strickland and Herenton have eschewed.

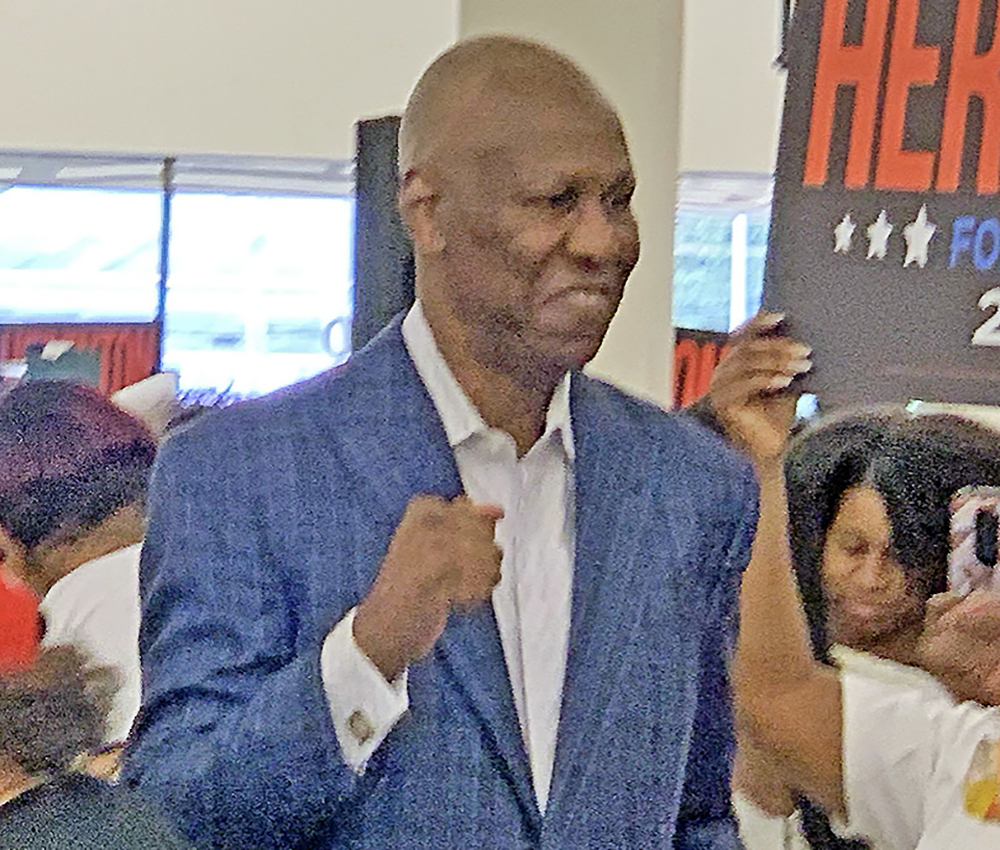

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

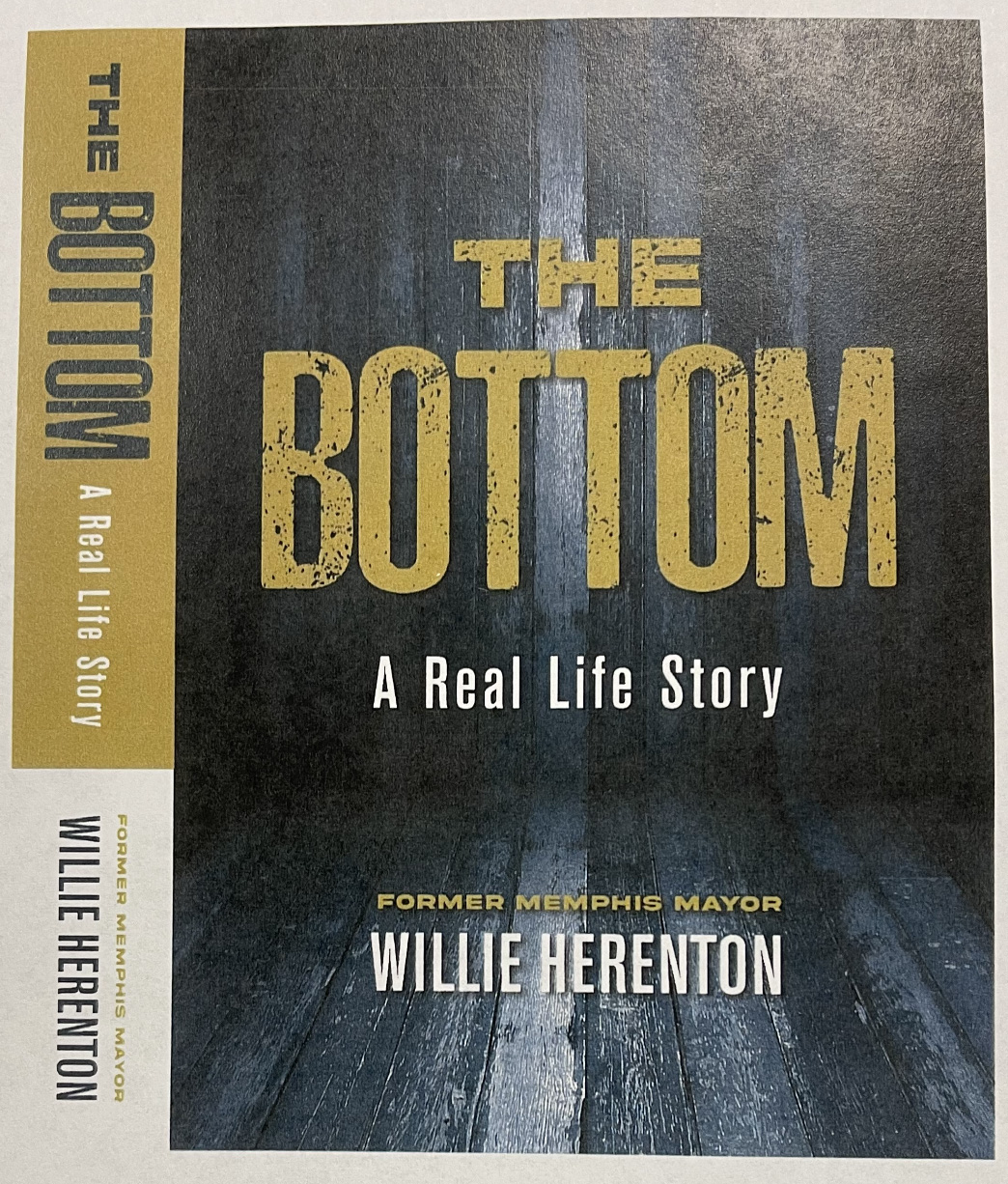

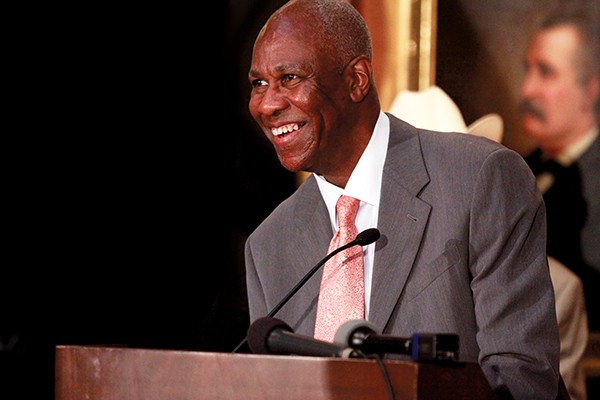

Former Mayor Willie Herenton

One of the more recent of these was last Sunday’s conclave of MICAH (Memphis Interfaith Coalition for Action and Hope) at Mt. Vernon Baptist Church Westwood — an event featuring thousands of attendees from numerous civic-minded organizations, all energized and in not much need of extra stoking. Of the mayoral hopefuls, only four were in attendance — Sawyer, Terrence T.B. Boyce, Lemichael Wilson, and Pamela Moses. Moses, whose candidacy has been disallowed by the Election Commission but who has filed suit against her exclusion, got to speak; Wilson was not invited to speak, since he had not completed a written pre-registration form for the event.

Current County Commissioner Tami Sawyer

That left only Boyce and Sawyer with a chance to make an impact. For an unknown, Boyce didn’t do badly in celebrating the event and its participants and in associating himself with it all. Sawyer did not exaggerate when she suggested that her own stated objectives and “every one” of MICAH’s bullet points were one and the same: “from transportation equity and economic equity to support for human rights, so on and so forth, and, most importantly, education and opportunity for our youth.”

For his part, Strickland was at a meet-and-greet at a supporter’s house elsewhere in town, one of a series of such events he has come to employ. And Herenton had, since the beginning of early voting on Friday, been busy organizing the bus “caravans” to the polls that would win the election for him — or so he had promised at a rally last month. So involved had he become in the planning that he was a no-show at an event of his own on Friday evening — a “sunset with Doc on the river” occasion, now postponed until later, that was to have been held on Mud Island.

Early voting is indeed underway and will continue through Saturday, September 28th. Voting will conclude on Election Day, Thursday, October 3rd. Between the mayoral contest and other races, there will be 63 candidates for Memphians to choose from. Besides the aforementioned 11 mayoral candidates, there are 52 candidates on the ballot for 13 Memphis City Council seats, nine for the City Court Clerk position, and five for judgeships in City Court.

There is also a referendum for a half-cent increase in the sales tax, the initial proceeds of which are meant to restore health care and pension benefits lost to first-responder public employees in recent years, with any remaining proceeds to be applied to street maintenance and/or pre-K education.

The election is being held in the year of the city’s own bicentennial; Memphis having been founded in 1819. Our 58th mayor since then, Jim Strickland, took office in 2015, having defeated then-incumbent Mayor A C Wharton, whose comeuppance was due in part to the trimming of benefits mentioned above.

One basic problem for challengers Herenton and Sawyer is that, financially, they lack the means to contend on even terms with Strickland, who brought a campaign kitty of $1 million into the campaign. And prime media of the free kind — especially, as indicated, in the form of organized debates between the contenders — has been hard to come by.

While both of Strickland’s opponents have appealed to what they hoped were legions of dissatisfied citizens, Herenton’s base is obviously African American as such, while Sawyer’s is, in a paradoxical sense, both broader and narrower.

Herenton’s pitch is basically to the long-depressed citywide population that he had empowered with his precedent-setting victory of 1991, as well as to the residual auld lang syne of his governmental experience and years in power. Important supporters of Herenton are public-employee unions, including the Memphis Police Association.

During his 18 years at the helm of city government, Herenton, who was actually the candidate of the Memphis establishment in 1995 and 1999, had enjoyed moments of genuine across-the-board support, though most of this has dissipated with time.

Sawyer, with her slogan of “We Can’t Wait,” has appealed primarily to younger voters, white and black. The county commissioner represents the eternal appeal of idealism per se, and through her determined activism over recent years, Sawyer has already achieved quite a lot — notably in her successful marshaling of opinion against the retention of statues and markers glorifying both the Confederacy and, implicitly, the creed of slavery.

Strickland, assisted by strategist Steven Reid, worked an effective simplification and synthesis of political issues in his campaign of 2015, and it gained him a victory over incumbent A C Wharton, who had once appeared unbeatable. As a councilman for two four-year terms, Strickland had been primarily a budget hawk and anti-taxer and had thereby solidified his hold on many Memphis homeowners.

Leaving that rhetoric of austerity aside (even if still coasting on its dividends), candidate Strickland in the 2015 campaign harped on three issues and three alone — public safety, blight, and accountability — all wrapped in the catch-all slogan of “Brilliant At the Basics.” Strickland defended this triad of talking points as a “vision” in 2015, and it has been transformed over the three and a half years of his tenure so far into the basis, more or less, of the self-administered report card of his reelection platform in 2019.

Launching his official “kick-off” in early August at his campaign headquarters, the old Spin Street store at Poplar and Highland, Strickland, whose usual practice is to cite pothole repairs as a major achievement, boasted of an accelerated hiring of police officers, a doubling of the city’s paving budget, and the use of “data” to “drive government decisions.” He would quickly amend that formulation to “data and good people,” working in a brag on city employees.

Strickland served up some stats, claiming a quickening of the city’s 911 response to an average of seven seconds per call; an enhanced survival rate at the city’s animal shelter; an increased MWBE percentage (rate of contracting with firms owned by women and minorities); a 90-percent increase of summer jobs for youth; and 22,000 new jobs in three and a half years. “All of that without a tax increase,” Strickland proclaimed, promising more via his administration’s Memphis 3.0 growth plan. “Memphis does have momentum,” he assured attendees.

The Memphis 3.0 initiative, the city’s first comprehensive growth plan since 1981, is an ambitious prognosis of what should be done in the coming years. And in a sense, it involves a reversal of Memphis’ growth patterns since that former prospectus. In the previous 40 years, the city has sprawled eastward in a helter-skelter response to the various social upheavals of the late 20th century. The process was nonstop, and city government, merely to maintain a tax base and to stay within a country mile of solvency, annexed new developments — Parkway Village, Fox Meadows, Hickory Hill, and a whole array of new Potemkin villages in the vast eastern expanse of Cordova — virtually as fast as developers could create them, incurring thereby an obligation to provide essential services.

Over the decades, there were calls from good-government types for city-county consolidation, but the developing geographic/demographic schism had occurred for a reason. The occasional referendums on the consolidation issue required “yes” votes in both city and county, and were inevitably defeated.

The last such test occurred in 2010, when the voters inside the city’s boundaries gave a consolidation proposal a bare okay, but voters of the outer county overwhelmingly said no. The next few years would see a reprise of sorts when the Memphis City Schools Board abandoned its charter, a majority of its members fearing that a new Republican legislative majority in Nashville would diminish state monies for city schools to fund a new special suburban district.

The outcome? An attempt at city-county school consolidation, which Shelby County’s six incorporated suburbs managed ultimately to fend off with friendly state legislation allowing for new municipal school systems.

These newly hardened buffer provinces magnified the problems of the city of Memphis, geographically spread thin and now effectively landlocked by other new state laws restricting its annexation rights. Hence, Strickland’s Memphis 3.0 plan, one central thrust of which was to emphasize, not outward-bound growth, but the in-filling of available or vacated urban areas. As Strickland and his surrogates now put it, “Build up, not out.”

While, implicitly, the mayor’s two major opponents accept Strickland’s concept that Memphis’ future is inward-looking, they differ as to what that concept exactly means, and they take issue with the mayor’s basic assumptions.

In appearances before union groups and other, largely African-American audiences, Herenton has scoffed at “this so-called momentum,” which he says exists so far mainly for developers.

Herenton disputes Strickland’s claims of being “brilliant with the basics,” saying, “I’ve never seen so many iron plates and potholes on the streets of Memphis in my lifetime.” And he calls attention to a recent rise in the city’s murder rate. In a radio interview with Memphis Police Association president Mike Williams, who himself ran for mayor in 2015 but is supporting Herenton this time around, the former mayor said, “Mike, if we don’t get at the root causes of family deterioration, of children being neglected, we’re not going to solve this crime problem.”

While naming economic development one of his own highest priorities, Herenton expressed concern that the current city establishment “gives away the store” by extending excessive tax breaks and incentives while overlooking the needs of ordinary citizens. Mocking the old saw that “a rising tide lifts all boats,” Herenton proclaimed, “If you don’t have a boat, you’re not going to rise.”

The former chief executive sees himself involved in a “one-on-one” contest with Strickland, minimizing candidate Sawyer as a “distraction” and implicitly rebuking her role as a civic gadfly. “I don’t think leadership can tolerate civil disobedience,” Herenton has said.

There’s no question that Sawyer is willing to confront established practices that, as she sees it, militate against less fortunate members of the Memphis population. She began her rise to prominence — and a national reputation — in 2014 as one of the leaders of the local Black Lives Matter movement, highlighting the too-often-deadly encounters between Memphis police officers and African-American youth. It was as the founder and principal strategist of “Take ‘Em Down 901” — an organization determined to rid Memphis of its Confederate statues — that Sawyer earned her stripes and enhanced public awareness.

While Strickland, himself long committed to statue removal, tried to work within the confines of state law and to coax permission from the Tennessee Historical Commission to remove the Confederate monuments from their pedestals in the parks, Sawyer led other activists in around-the-clock vigils around the statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in what had been renamed Health Sciences Park.

Said Sawyer at the time: “The people are saying that this is what they want. The people that they have asked to represent them have the power and the right to be radical in making this change.”

After finding himself blocked by the guardians of tradition in Nashville and goaded by the reformers at home, Strickland, working with legal adviser Bruce McMullen, devised a way of accomplishing the statue removal: The mayor used a loophole in the law that allowed him to deed over possession of the parks to an ad hoc nonprofit organization, which quickly removed the statues, legally, under cover of darkness.

Sawyer was anything but congratulatory. “You cannot give credit to the mayor and his administration for the removal of the statues and erase the fact that they participated in the arrest, detainment, surveillance, and silencing of the activists and protesters who brought the issue back to the public eye,” she said.

In 2018, Sawyer was elected to the Shelby County Commission, from which vantage point she continues to speak out for what she sees as long-overdue change, highlighting such issues as outmoded public transportation, the need for criminal justice reform, and implementation of a local $15-an-hour minimum wage. In every sense, her slogan, “We Can’t Wait,” is a clear rendition of her worldview.

With only a fortnight left in the race, Strickland remains the clear favorite, with support from a wide demographic range, as would be indicated by a recent prayer breakfast where he was warmly endorsed by a gathering of prominent black pastors.

Herenton has meanwhile been able to hold mass gatherings of mostly African-American supporters. And Sawyer’s enthusiastic reception at last Sunday’s MICAH conclave suggests something about the breadth and energy of her base. The mayor’s private polls show him with a comfortable lead. But both Herenton and Sawyer are determined to take the fight to the incumbent, and anything can happen in the campaign’s final two weeks. Stay tuned.

City Council Races

The Memphis City Council has two decidedly different kinds of seats; the six “Super District” seats — three of which are in predominantly black Super District 8, and three of which are in white-inflected Super District 9. All six contests are, as is the case with the mayor’s race, winner-take-all affairs. The other seven seats are more traditional, representing the seven individual geographic districts that comprise the city. In the “District” seats, runoff elections are held if no one candidate gets a majority on October 3rd. Which raises another point of contention.

Shelby County Election Administrator Linda Phillips had arranged for the 2019 election to be conducted via the process of Ranked Choice Voting, which obviated runoffs by allowing successive re-samplings of votes cast by out-of-the-running finishers to determine a winner. But a de facto collaboration of incumbent council members and opponents of RCV in the state election coordinator’s office managed to suppress the instituting of that reform, which had twice been approved in referendum votes by Memphis voters. Adherents of RCV, also called Instant Runoff Voting, intend to keep pressing for its use in future elections.

The 13 city council races break down this way:

District One (Raleigh, Northeast Memphis): This race is essentially a rematch between incumbent Sherman Greer, a former aide to two 9th District Congressmen, Harold Ford Jr. and Steve Cohen, and Rhonda Logan, president of the Raleigh Community Development Corporation and the protégé of several north Memphis politicians, notably State Rep. Antonio Parkinson. After a prolonged stalemate to fill a council vacancy, Greer got the interim nod from a council vote over Logan last year. Dawn Bonner is a third hopeful.

District Two (Outlying East Memphis, Cordova): Incumbent Frank Colvett, sales director at Greenscape, Inc., is expected to have little trouble with token opposition from novice candidates John Emery and Marvin White.

District Three (Southeast Memphis, Hickory Hill, Whitehaven): Incumbent Patrice Robinson is strongly favored over challenger Tanya Cooper.

District Four (Central City Area): Though she remains favored, incumbent Jamita Swearengen may have a fight on her hands with challenger Britney Thornton, the Ivy League-educated founder of JUICE Orange Mound, a community development organization.

District Five (Midtown, East Memphis): Sales executive Worth Morgan, the incumbent, is what his name sounds like: He’s the son of investment-guru Allan Morgan of Morgan-Keegan fame. Well-funded and well-spoken, he won easily in 2015 and has become a council fixture, though one demonstrably capable of independent actions. In 2019, he is up against John Marek, a stylish maverick, cannabis pioneer, and founder of the Dignity PAC, dedicated to criminal justice reform. This race could catch fire, given the district’s eclectic demographics.

District Six (South Memphis, Downtown, Riverfront): This race has a lot of sideshow activity, with a father-daughter contest (Perry Bond vs. Theryn Bond) and a gay policeman/minister Davin Clemons bearing the endorsement of County Mayor Lee Harris. But former seat-holder Edmund Ford Sr. is favored in a bid to reclaim his old seat. Other candidates are Paul S. Brown and J. Jacques Hamilton.

District Seven (North Memphis, Frayser): The trick here is to see who can make it into a runoff with incumbent Berlin Boyd, who has constantly been under fire for his imperious attitude and penchant for wheeling, dealing, and flirting with potential conflicts of interest. Among the eight challengers looking for that ultimate one-on-one are Michalyn C.S. Easter-Thomas, who has the endorsement of this year’s People’s Convention, community activist Thurston Smith, and political newcomer Jerred Price. Others are Toni Green-Cole, Jimmy Hassann, Will “the Underdog” Richardson, Catrina L. Smith, and Larry Springfield.

Super District Eight, Position One: Gerre Currie, the current District 6 incumbent, eschewed that race in deference to Edmund Ford Sr. and is running in this tight field instead. Her major opponent is probably lawyer J.B. Smiley, who is running hard. Reformer Pearl “Eva” Walker has a passel of endorsements and a nod from the People’s Convention, and Darrick Dee Harris is a familiar Democratic Party activist. Nicole Cleaborn rounds out a crowded field.

Super District Eight, Position Two: Incumbent Cheyenne Johnson, running as a Democrat, went undefeated for several terms as county assessor, even in Republican-dominated eras. So she has to be favored here against Marinda Alexandria-William, entertainer Frank Johnson, Craig Littles, and Brian L. Saulsberry.

Super District Eight, Position Three: Incumbent Martavius Jones, a stockbroker and former Memphis School Board member, is often a swing vote on the council, and should prevail over newcomer Cat Allen, R.S. Ford Sr., Gerald Kiner, Pam Lee, and Lynette P. Williams.

Super District Nine, Position One: This is a classic one-on-one contest between developer Chase Carlisle, who is an entry from the big-bucks Caissa Public Strategies stable, and grassroots candidate Erika Sugarmon, the socially conscious daughter of the late civil rights eminence Russell Sugarmon.

Super District Nine, Position Two: Incumbent Ford Canale has important establishment support, but he has challenges from Deanielle Jones and Mauricio Calvo. Calvo, the longtime executive director of Latino Memphis, is a newly naturalized citizen making his first political run and, upon entering the race, made a point of coming out as bisexual.

Super District Nine, Position Three: University of Memphis Development specialist Cody Fletcher would appear to offer the only real challenge to Jeff Warren, a former school board member who has impressively diversified support from numerous sources and has been the leading fund-raiser among council candidates. Charley Burch raised a policy issue or two before endorsing Warren, and Tyrone Romeo Franklin rounds out that field.

At issue overall is the question of whether grassroots city council candidates any longer have a serious chance against those favored by the city’s business elite, a group which has in recent years used its financial resources, in effect, to bypass the dialogues and forums of pure democracy.

Buttressed by high-dose advertising and veritable forests of yard signs, the favored candidates can — and sometimes do — conduct entire campaigns while remaining remote enigmas to the voting population. For better or worse, the last several councils might as well have been hand-picked by the development community, which seems determined to prevail in its choices once again.

See “Politics,” for information on judicial races and the race for City Court Clerk.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker