Our nation has a distinct literary tradition, which some dub the American bildungsroman, that delves into the provincial life of a protagonist in his or her youth, then reveals, layer by layer, the stages of learning and mind-opening encounters by which the narrator learns of the wider world, thereby transcending provincialism and achieving a kind of worldly wisdom. And such books, often loosely autobiographical, can, by way of setting the scene for the protagonist’s eventual escape, offer rich and nuanced portraits of the small-town milieu in which they were raised. Writings as disparate as Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel and Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory paint indelible portraits of daily existence in small towns.

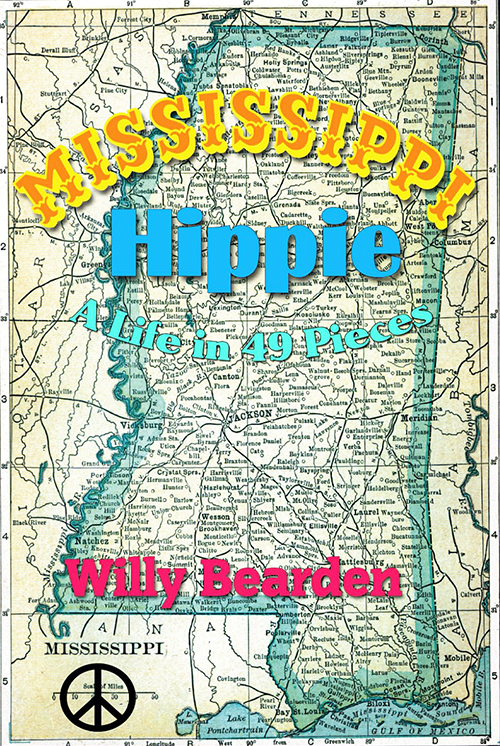

Now, local author, filmmaker, musician, and photographer Willy Bearden has produced such a work about his hometown of Rolling Fork in his semi-fictionalized memoir, Mississippi Hippie: A Life in 49 Pieces. And, in its segmented, episodic telling, it reads like another great fragmented bildungsroman, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio — but with a laconic Southern drawl.

Like Anderson’s masterpiece, Bearden’s memoir is, as he notes in the first sentence, “a work of literature.” And yet he’s committed to telling the story of his life. “Memory has its own story to tell,” he writes. “But I have done my best to make it tell a truthful story.”

Bearden has an artist’s commitment to truth-telling, and, as becomes clear over the course of his youthful epiphanies, that unflinching honesty served him well in his quest for a life of some significance. As the Tennessee Williams quote beginning the book states, “No one is ever free until they tell the truth about themselves and the life into which they’ve been cast.”

For Bearden, that starts with a long, hard look at his father. This being a somewhat conversational read, though, it takes him a while to settle on the opening scene. First, he tells the reader of his curious habit, at the age of 11, of listing everyone he’d known who had died. It marks a vivid through-line to the book itself, written in his 70s, filling that same need.

Then, skipping ahead in time, Bearden confronts the idea of “woke” culture, a descendant of the “hippie” culture that Bearden threw himself into as a teen in the ’60s. And, as he writes, “I am proud of my hippie roots,” yet the book makes clear that such pride comes after long years of confronting the very un-hippie culture of Rolling Fork.

The book really gets started when, after such preambles, Bearden unearths a short story he wrote in 1984. His father has been returned to the home where Bearden, then 10, was being raised by his mother. “What until now had been the complacent, resigned look of an alcoholic had turned wild and frantic as if some demon inhabited his skinny 130-pound frame.” As the father is unceremoniously dumped into a bed, the stage is set for Bearden’s early years and the chaotic family life he endured.

But, as reflected upon by the author decades later, it’s a thoughtful portrait of such chaos. That’s true of any of the local characters young Bearden interacts with, as the stories skip back and forth in time, often hinting at Bearden’s development as a thinker and a questioner later in life. For, while he wasn’t a great student and didn’t really learn to read until after he was 10, he was doggedly curious and reflective. The folk songs his brother played him jolted him into imagining other values and life ways, and the growing counterculture of the ’60s only confirmed those humanistic values, even if he met some sketchy characters along the way. That in turn served him well as he ventured out into the world (hitchhiking widely from 1969-1976) and greeted all he met with a mixture of Sherwood Anderson’s keen observational eye and Woody Guthrie’s everyman approachability.

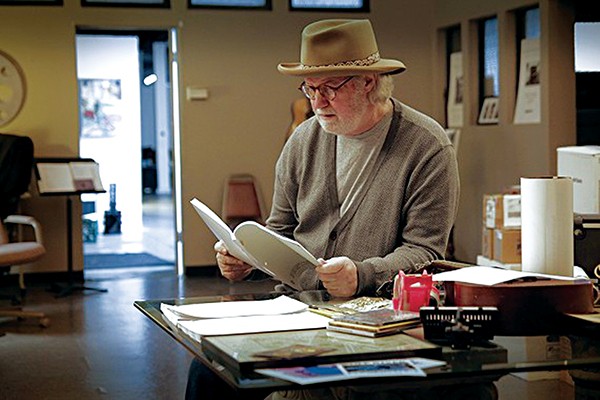

That hopeful, clear-eyed, and even bawdy approach to the world rings out from every page of this book, and it’s still heard in Bearden’s current work as a historian, filmmaker, and raconteur. Knowing that Bearden became a key player in Memphis’ progressive community helps make sense of what he passed through to get there, from the unsavory drunks to the homespun wisdom of Rolling Fork’s working people. Seeing the poverty and racism of his hometown didn’t give him a permanent scowl. Rather, it only made him more determined to keep searching, just over the flat Delta horizon, for some kind of redemption.

Burke’s Book Store will host a reading and book signing by Willy Bearden on Thursday, September 5, at 6 p.m.