Meddlesome Brewing Co.’s 201 Hoplar is (once again!) the best beer in Memphis, according to the 1,634 voters in the 2019 Memphis Flyer Beer Bracket Challenge, graciously sponsored by all of the great folks at Aldo’s Pizza Pies.

The Dirty ‘Dova dudes were just getting off the ground when they took home the coveted VanWyngarden Cup last year. They brought the cup back to us during our Match-Up Monday event at Aldo’s at the beginning of this year’s challenge. After a quick trip to C & J Trophy and Engraving, we gave the cup right back to Meddlesome last week during a Facebook Live event. By now, they’ve surely returned the cup to its spot in the Meddlesome taproom, where it will reside for another year.

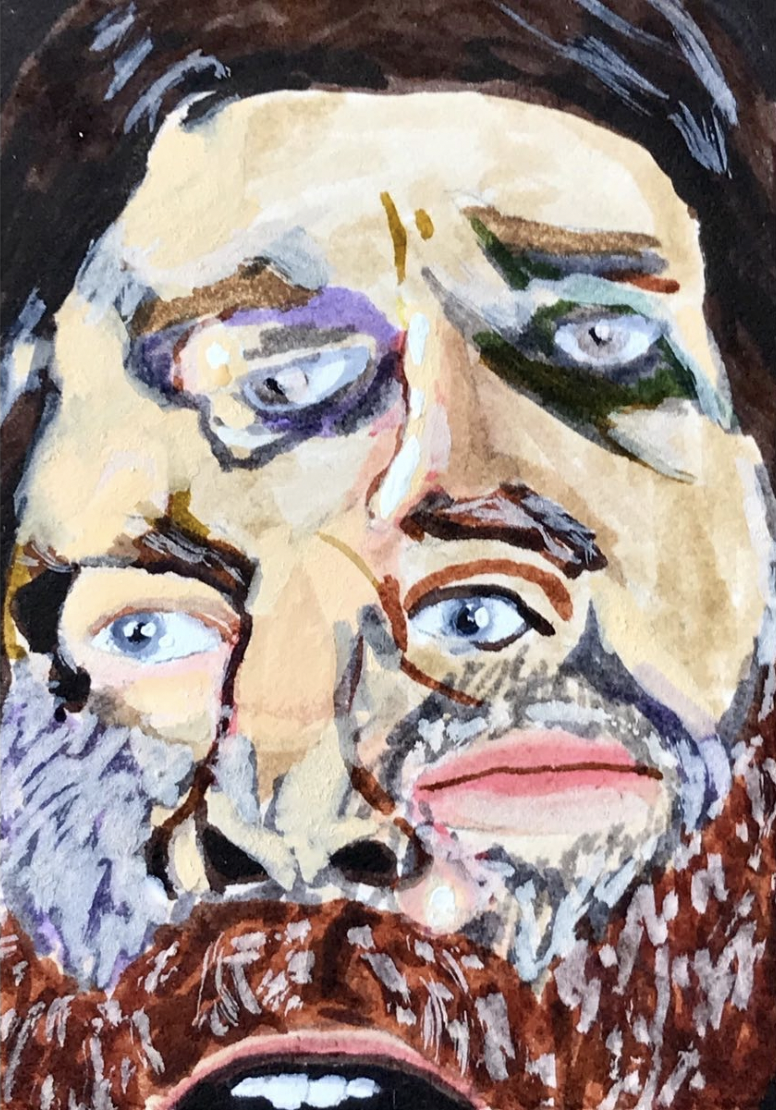

Meddlesome brewer Ben Pugh

“We’re still blown away,” says Meddlesome co-founder and brewer, Ben Pugh. “It’s crazy. We didn’t expect it the first year. We definitely didn’t expect it in the second year. It’s been wild and humbling.”

Says co-founder and brewer Richie EsQuivel: “Last year was, like, ‘what the hell?’ I was hoping we could get into the last four this year, but definitely did not think it’d be 201 [Hoplar] again.”

EsQuivel calls 201 a West Coast-style American IPA, “straight up and through and through.” He says new IPAs are “soft and fruity,” while 201 Hoplar meddles with that. (Don’t worry. You’ll see that pun again later on.)

Chris Hamlett and Skyler Windsor-Cummings of Meddlesome with Flyer writer Toby Sells.

“This beer is intended to be kind of aggressive and bitter,” says EsQuivel. “It’s super-pineappley with citrus fruits.”

We changed up the Beer Bracket Challenge this year. We did away with the four categories — light beer, dark beer, IPAs, and seasonals — and let the breweries choose any four beers they wanted to compete, regardless of style. This made for some interesting matchups. Ghost River’s Grindhouse vs. Crosstown’s Margarita Gose, for example.

In the first round, 624 people cast 3,416 votes. Most of these voters were in Midtown, but there were a surprising number from New York and Massachusetts. Somebody voted in Spain. In round two, 571 voters cast 2,911 votes from as far away as Miami to Bellingham, Washington, a town just outside Vancouver.

Meddlesome dominated our Final Four with Broad Hammer, 201 Hoplar, and Brass Bellows all taking slots. Memphis Made’s Fireside was the fourth member of the dance.

“Fireside is easy-drinking,” says Memphis Made co-founder Andy Ashby. “It’s super-laid-back, just like Memphis. It’s accessible and easy to fall in love with.”

But it was Meddlesome’s Broad Hammer brown ale and that aggressive 201 Hoplar IPA that went to the title fight. It was a close battle; 201 Hoplar won by only five votes.

Water. Malt. Yeast. Hops.

I’ve made beer for years now. Here’s my latest recipe.

• Walk into Sweet Grass Next Door.

• Find Bailey (or Dougan, if you must).

• Say, “Bailey, may I have a” and then say the name of a beer they have.

This produces optimal results every time. I get that perfect blend of roast-i-ness, bread-i-ness, hop-i-ness, with a perfect mouth feel and a cold, clean finish. Every. Single. Time.

Listen, I don’t know shit about beer. I can confidently say that after spending a week visiting the crazy-smart, hardworking brewers at Ghost River, Meddlesome, Memphis Made, High Cotton, Wiseacre, and Crosstown. Those folks know a LOT about beer.

They can trace a beer style back in time and across a world map, like a genealogist with a family tree. They can trace the ingredients they use back to their literal roots. They can talk about beer and sound like a fanatical foodie and a chemical engineer in the same sentence.

On the Facebook Live stream for our Match-Up Monday event, I said some of the best beer in America is made right here in Memphis. I stand by that. I drink local beer wherever I go, and I always compare it to stuff back home, asking myself, “Is it as good as Traffic IPA, or Tiny Bomb, or Mexican Lager, or Fireside, or Brass Bellows, or Grindhouse?” And no matter what I think, I’m always glad to come home to my Memphis favorites.

I decided to fix some of my beer ignorance. I talked with brewers about their processes and their ingredients. I broke it down to beer’s four basic elements — water, malt, yeast, and hops. I learned a lot and have a new appreciation for brewers and the beer they make. But I’m not quite smart enough to change up my recipe anytime soon.

Water

The skies above Meddlesome Brewing are a dark battleship gray. Inside, a heavy quiet lays upon the bar. But through a door and around tall, silver tanks, a gleaming white light exposes a scene that could be a laboratory, a laboratory that smells of bread and plays Alice In Chains over a noisy din of equipment whirring.

It’s a brew day, and the brewhouse is busy. Guys in rubber boots climb steel ladders to open steaming lids on massive silver tanks and check the couplings on long black hoses that snake across the ground, round as a python and tough as a snow tire. After the work of the day and a few weeks to ferment, they’ll have Broad Hammer and McRoy’s Irish Stout.

“Our [Memphis] water is a fantastic vehicle for our beers,” says EsQuivel. “Beers are 90 percent water. So, it’s obviously super important.” Meddlesome’s Pugh says it takes about eight gallons of that famous Memphis water to make one gallon of beer. But Meddlesome reclaims and reuses much of that water.

EsQuivel says they may adjust the pH of the water and add some salts or acids to it sometimes. But mostly they don’t “meddle” with it, he says in a self-aware, corny dad joke.

Soft rain beats against High Cotton’s taproom windows. The room’s big “BEER!” sign bathes upturned barstools in a soft, yellow glow.

Through two enormous doors, bright lights fall on brick walls above a concrete floor and massive copper-colored tanks. It’s a brew day, and the brewhouse is busy. Guys in rubber boots check gauges and climb steel ladders to open steaming lids on those massive, copper-colored tanks. They’re making a batch of High Cotton’s new Thai IPA and a batch of Scottish Ale.

“As Memphis brewers, we really don’t have to do anything to the water to make good beer,” says High Cotton co-founder and brewer Ryan Staggs. “We also don’t have to install a super-expensive, water filtration system. Out west, water is super-expensive, but it’s also terrible. A lot of places in California will even have to use reverse osmosis just to get that blank slate that we get right out of the tap at a great price.”

Water is also the most local ingredient source Memphis brewers can use in their beers. The rest of the main ingredients have to be shipped from specialty sources (for now, anyway).

Malt

Crosstown Brewing’s massive, yellow logo pops off the side of its massive, gray building. Inside, huge silver tanks sit in neat rows under high ceilings. Those tire-tough and python-thick hoses snake along the floor.

The place is nearly deserted, until two brewers come along, each with a French Truck Coffee in one hand and a pastry in the other. Soon they are busy, making a double batch of Traffic IPA.

I point to a large bag of something with the word “Canada” written across it. Clark Ortkiese, Crosstown Brewing co-founder and brewer, says it’s their base malt.

The very patient brewers of Memphis explained to me that malt is malted barley, the same grain as in a beef and barley soup. Ortkiese says maybe 90 percent of every beer made in the world is made with a base of malted barley. If you ever see a plant that looks like wheat on a brewery logo, it’s probably barley.

Brewers will use malt and some other grains for different kinds of beer. The list of all grains used in a beer is referred to as the beer’s “grain bill.”

Barley is grown and harvested and then sent over to a malter. There, the grain is soaked for a time, dried, and roasted. That roast time will determine much about the beer. Lightly roasted malt will give you lighter beers, a pale ale or a pilsner, maybe. A golden-roasted malt will give you a Scottish ale or an Oktoberfest. A dark roast, of course, will give you darker beers, like a Guinness.

Ortkiese explains that the big Canada bag contains “just plain malt. You can call it two-row or pale malt. It’s a base malt. It’s all that goes into Traffic.”

Steve Winwood’s “Roll With It” blares over the darkened taproom at Memphis Made. A pallet jack, tools, and sacks of grain spread across the floor where typically sit neat rows of tables and benches.

By the late afternoon, the brewers are working on their second batch of the day. Back in the lighted brewhouse, they gang around a silver tank, opened at the top and just bigger and taller than a pool table. It’s filled to the brim with what looks like oatmeal. It’s not, of course. It’s that famous Memphis water and that malted barley combined to make a sugary water. One day, that hot, sweet-smelling oatmeal-looking stuff (called a mash) will somehow become an ice-cold Fireside amber ale.

Memphis Made co-founder and brewer Drew Barton says a lot of his company’s grain comes from Germany, but they get some speciality stuff from the U.S., Canada, and England. Outside of water and know-how, you can’t really source a lot of beer ingredients locally, he said.

“We don’t grow hops around here,” Barton says. “We don’t grow barley around here. There’s no yeast labs around here. At this point, it’s more of the skill set … of the brewer and the equipment you use that’s more important than if you got the ingredients right down the street. The source is important but not the locality of it.”

Yeast

Barton says much can be done along the brewing process to change the flavor components of beer. Yeast, he says, is one the biggest contributors to flavors “that people don’t realize.” And it’s not just the casual beer drinker who doesn’t get it.

“The most important ingredient in brewing was the last one discovered, because yeast is a single-celled organism that is invisible to the naked eye,” according to All About Beer magazine. “Still, brewers have long known that some unseen agent turned a sweet liquid into beer. Long ago, the action of yeast was such a blessing, yet so mysterious, that English brewers [in the Dark Ages] called it ‘Godisgood.'”

Barton says yeast is vitally important to flavors. “We can have 500 gallons of wort [beer before yeast and fermentation] and split it up into five 100-gallon tanks with five different kinds of yeast in them,” Barton says, “Even though everything started out the same, you’d get five very different beers.”

Ortkiese rattles off the name of the yeast used at Crosstown — US-05 California Ale yeast — quickly, from the top of his head. But then, his eyes light up as he courses through the history of that yeast strain from a now-defunct California brewery to its rediscovery and “rescue” by Ken Grossman, billionaire founder of Sierra Nevada.

“I’m guessing here, but I’ll bet half the beers in the United States are fermented with that yeast; it’s just a workhorse,” Ortkiese says. “It’s very neutral. So, it lets all the hop flavors come forward.”

Yeast also gets you drunk.

Those little fungi eat all that sugar we made with the water and malted barley, remember? It chews it up somehow and poops out — you guessed it — alcohol. Thanks, yeast. You really are the best.

Hops

But for the gentle hum of some equipment and a hiss of running water somewhere, things are quiet at Wiseacre, relative to the size of its big brewhouse. The brewers are busy, but they’re spread out, working somewhere amid silver tanks that seem two stories tall. Somewhere in here, I think to myself, is an Ananda that I will drink sometime in the future. Weird.

Inside a walk-in cooler, brewer Sam Tomaszczuk pours bright green pellets from a futuristic, metallic-silver pouch. While you might not recognize them in their pelletized form, you’ve seen hops before. Have another look at a brewery logo. You might find a small, green plant the same shape as strawberry. Heck, a hop plant is the central feature of Meddlesome’s logo.

Hops are little green flowers, cousins to marijuana. Brewers primarily use hops to bitter beer, to balance out that sweetness from that sugary barley water.

“There are a lot of beers that are quite hoppy out there that aren’t bitter at all,” Tomaszczuk says. “We have people who say they don’t like a hoppy beer and then we have them try something like Adjective Animal. It’s 8.6 percent alcohol … so it has a lot of sugars to it. It’s actually kind of sweet, compared to some of our other beers. So, when people try that, they tend to like it, even thought that’s a ‘hoppy beer.'”

Tomaszczuk pours those green, pelletized hops into a the steaming hole of a massive silver tank. In a few weeks, it’ll be a Hefeweizen, a light wheat beer, just in time for spring.

Chunky, heavy-metal guitar riffs blend somehow over the hiss, clatter, and conversation spilling out of the open bay door of Ghost River. It’s a canning day, and the brewers are canners for the day.

A pallet of naked, empty, silver cans glide from their stacks in satisfying single file through a machine that would make Willy Wonka smile. The cans are filled four at a time, sealed with a lid, twirled with a label, and six-packed by hand. It’s the very first time Ghost River has canned its new Grind-N-Shine, a light cream ale with coffee and vanilla. The beer is cold, and the freshly filled cans sweat in the tropical brewhouse environs.

Back in the quiet of the taproom, Ghost River head brewer Jimmy Randall explains that it was “time to move forward.” Ghost River replaced its 1887 IPA with Zippin Pippin, and hops were a big reason why.

“We really wanted something … that would reflect those flavors that you get in IPAs and the hop profile was a big one,” Randall says. “We wanted to give it those big, up-front hops, the aroma, the flavor of them. So, we changed the way we hopped the beer completely.”

Add hops to the end of the boil, Randall explains, the more aroma you’ll get. Boil them longer, you’ll get a more bitter beer. Add hops at the end, you’ll get different flavors. And the types of hops you use will change everything.

“So, take your Centennial hops, for example, which are kind of your classic, American IPA hops,” Randall says. “Bells Two Hearted IPA? That is 100 percent Centennial hops.”

Mosaic hops will give you juicy, tropical-fruit flavors, he says. Citra will give you citrus flavors.

Get Crafty

There are about 100 craft breweries in Tennessee. About two dozen of those are in Nashville. Knoxville has 15 along its “Ale Trail.”

The craft beer scene is still fairly new in Memphis. Boscos was Tennessee’s first brewpub, opening in 1992. Ghost River opened here in 2007. We’re now about five years from the Great Craft Awakening of 2013, the year that saw High Cotton, Wiseacre, and Memphis Made open. Since then, the city has added Meddlesome and Crosstown, each of which has been open for just more than a year.

The Memphis scene isn’t small. It’s right-sized, and more is on the way. We’ll hopefully see Grind City Brewing in next year’s Beer Bracket Challenge. They’re planning to open in July. Plans to open Soul & Spirits Brewing in Uptown were revealed last week. There are more breweries coming, I’m told, but nothing we can report just yet.

Until then, support your local craft brewers. Go drink a beer. And feel free to use my recipe.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  High Cotton Brewing

High Cotton Brewing