The Huntington Hills apartment complex in Raleigh looks like any other slightly distressed complex in the city’s inventory of aging, blighted apartment communities. Some of the multi-family buildings in the gated complex are occupied, with bright red flowers sprouting around the walkways and cars parked out front. But other buildings on the site are boarded-up, mini-ghost towns without a single car parked outside.

Out of the back windows of one of the boarded two-story buildings, residents (if the building had any) would have sweeping views of the serene Wolf River, surrounded by thick patches of woods.

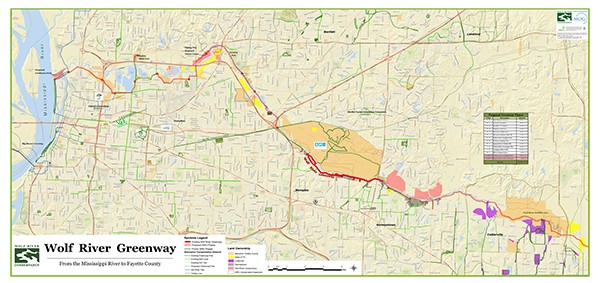

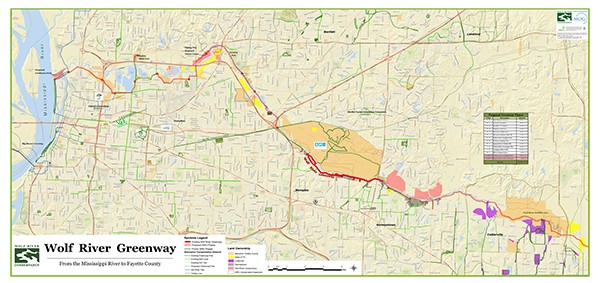

In a few years, those residents would have back-door access to the future Wolf River Greenway (WRG), a 36-mile walking and cycling trail that will follow the path of the Wolf River from Collierville to Mud Island. The Wolf River Conservancy (WRC) broke ground on a 20-mile Memphis stretch of the trail in late September, and they plan to have the entire path constructed by 2019.

Deborah Newlin, a Sabal Financial Group asset manager, represents the California-based bank that owns Huntington Hills, which is only 51 percent occupied and went into foreclosure earlier this year. They’re starting renovations on the units’ interior now, and the exterior will be revitalized in 2016. Thanks to the greenway plans, Newlin sees potential for the property and the surrounding Raleigh community.

“Asthetically, [the greenway] will add beautification, and it will add a better sense that this is a safe place to come to,” Newlin said.

Huntington Hills is just one stop on the WRG, which will be the only continuous trail leading from one end of the county to the other. Since the greenway will follow the path of the Wolf, much of it will run through uninhabited areas — wetlands, thick woods, and other natural gems hiding in the city’s urban core. Other portions will traverse impoverished communities, providing a new transportation route for low-income residents without cars. And it will provide connections to the Shelby Farms Greenline and other bike lanes.

The Greenway Today

“We believe we’re building a corridor of opportunity,” said Keith Cole, executive director of the WRC. “It’s more than just a 12-foot-wide paved hiking and biking path. As we go through these diverse neighborhoods — downtown, Midtown, Raleigh, Frayser, East Memphis — we can just imagine increasing the connectivity of those neighborhoods.”

The 20-mile or so city stretch of paved path will add a western connection to the existing 2.6-mile stretch of the WRG, which runs from Walnut Grove to Shady Grove along the southern bank of the Wolf and was completed in 2010. In 2012, it was extended eastward to connect with the Germantown Greenway running adjacent to Humphreys Boulevard.

and after (below).

Although the Germantown Greenway is maintained by the city of Germantown, it follows the path of the Wolf, and the WRC considers it part of their continuous WRG system. Germantown is currently planning to extend its greenway 2.5 more miles to Cameron Brown Park, making it only a mile away from a connection with a planned segment in Collierville.

Between April 13th, 2014 and April 13th of this year, the city counted more than 187,000 cyclists and pedestrians on the WRG.

“Our counts grew by 100 percent when we connected the greenway with Germantown,” says Bob Wenner of the Wolf River Conservancy. “So what happens when we connect with the Shelby Farms Greenline or with bike lanes in other parts of the city? The potential is there for it to come to a million users a year on the Wolf River Greenway.”

The Master Plan

The proposed WRG will begin at the head of the existing greenway near Walnut Grove. From there, it will run northwest along the border of Shelby Farms Park and continue northwest to Kennedy Park, a 260-acre city park in Raleigh with nine baseball fields and two soccer fields.

Kennedy Park is where the WRC held its late September groundbreaking event.

“Kennedy Park is a beautiful park. It’s one of the largest in the city, and it represents the heart of this project,” Cole told those gathered in the park that morning.

From there, the greenway will follow the path of the river to Epping Way, a 66-acre abandoned Raleigh country club that’s now an overgrown natural area with wooded areas and a lake. The trail moves southwest and connects with Rodney Baber Park, an underused 77-acre city park with seven softball fields and one baseball diamond.

“In the ’70s and ’80s, [Rodney Baber] was a really busy place. A lot of people played softball there,” said Mike Flowers, administrator of planning and development for the city’s Division of Parks and Neighborhoods. “But into the ’90s, the park started experiencing a lot of car break-ins at night. Play dwindled to the point that it’s not really used now.”

The May 2011 flood destroyed the sports lighting, concession buildings, and restrooms at Rodney Baber; they were under five to seven feet of water. Flowers said the city is seeking grant funds from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Disaster Resilience Competition to make those repairs.

West of Rodney Baber, the greenway moves through North Memphis, adding a connection to the Chelsea Greenline, and then over to the northern tip of downtown. The WRC controls 80 acres of land on the north end of Mud Island, and they’re proposing a new park at the greenway’s end at the Mississippi River.

“There’s all this land and incredible views of the Mississippi River, so we thought ‘Why don’t we call it something besides Mud Island?’ It’s the confluence of the Wolf and Mississippi Rivers, and we kind of like the name Confluence Park,” said Bob Wenner, WRC greenway coordinator. “It’s one of those Kodak spots. It’s a great place to watch the ships come up and down the Mississippi.”

The WRG has a price tag of about $40 million. So far private foundations have committed $22 million, including a $5 million challenge grant from Hyde Family Foundations.

“One of our big priorities is connecting people through green assets, streetscapes, and transit,” said Lauren Taylor, the program director for Livable Communities at the Hyde Family Foundation. “I think this is so exciting, the sheer fact that it’s going through so many different neighborhoods from downtown to Frayser to Raleigh to Shelby Farms Park. There are so many sections that will be close to schools and churches.”

Some funding will come from the city, which has already committed $7.5 million over the next five years. The WRC has acquired another $1.6 million from the Tennessee Department of Transportation. They’ve raised $568,000 in individual donations. Cole said the WRC will go public with a capital fund-raising campaign in mid-2016 when they “start turning dirt.”

Epping Way

Just up James Road from Huntington Hills, tucked away on a dead-end road between two large apartment complexes, are two crumbling pillars flanking a padlocked gate. Once you step over the low gate, you’re led into a massive natural area.

There are worn, paved streets, but they’re closed to traffic, and nature has begun to reclaim them. A short walk along the pavement leads you to the foundation of an old building. Some of the vintage tile from the rooms that were once inside the long-gone structure remains. Ornate tiles with a floral pattern outline an area that may have been an old swimming pool.

Epping Way: before (above) and after (below).

There are overgrown tennis courts and a massive lake, where those in-the-know about hidden Memphis fishing holes come to get away from hustle and bustle of the city. The sounds of nearby traffic along James Road are completely blocked by the rustling whisper of blowing leaves and bird songs. The Wolf River runs nearby, just on the other side of the lake.

This is Epping Way. Its history is a bit of a mystery, but it’s believed to be the site of an old country club and the historic home of Berry Boswell Brooks, a big-game hunter whose exotic kills — lions, hippos, and other wildlife — were displayed in the Pink Palace Museum in the 1950s.

The WRC acquired the 66-acre site (and 55 additional acres surrounding it), and the planned WRG will run through it. Cole and Wenner are hoping to eventually turn the area into Epping Way Nature Center and possibly even move the WRC headquarters to the site from their office building in Midtown.

“Our primary goal is to get the trail in, but [Epping Way] could become an environmental center, maybe like the Lichterman Nature Center. But it would be more of an outdoor classroom,” Wenner said. “You’ve got a river, a lake, and a wetland there. Maybe we could train adults and children in using canoes on the lake, and once they’re comfortable, we could move them to the river.”

The Design

The WRC plans to build the greenway in short segments, and a one-mile segment through Kennedy Park is slated for development first.

“It will be controlled chaos for awhile. It will be all over the place, but eventually, it will all come together,” said Chuck Flink, a senior advisor at Alta Planning+Design, which is working on the greenway design.

Flink has worked on greenway projects across the country, including the Grand Canyon Greenway and the Northwest Arkansas Razorback Regional Greenway, a 36-mile trail near the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville.

Flink says the WRG will be a paved trail, so it will be accessible to cyclists, walkers, runners, wheelchairs, and baby strollers.

“We’ll have lots of boardwalks and bridges. I like to refer to it as changing the plane, so you’ll get above the tree-line or above the surrounding ground in places. That gives people different things to experience [along the trail],” Flink said.

Connecting Memphis

Clark Butcher, owner of Victory Bicycle Studio on Broad, said the greenway will provide a safer east-west connection to get cyclists and pedestrians across the city. Right now, Butcher said cyclists have to use a variety of protected and unprotected bike lanes and trails, some of which require cyclists to share the road with vehicles.

“There’s a huge false sense of security when it comes to bike lanes,” Butcher said. “But what the WRC is doing is providing a dedicated and protected lane. You’re off-road, and it’s not wide enough for a car.”

Cole and Wenner are hoping the greenway will appeal not just to cyclists who would use the trail for recreation, but also to lower-income Memphians who may not have access to a car.

“This will also become a low- to moderate-income transportation corridor, and there will be linkages with MATA bus lines,” Wenner said. “Somebody may bike to a certain point and then ride the bus the last mile to work or school.”

“The route will go through a lot of underserved neighborhoods,” adds Cort Percer, the Mid-South Greenways coordinator. “These are areas that are underserved in terms of access to green space, healthy food, transportation, recreation, and exercise opportunities. The greenway will be a path around the barriers — I-40, high-traffic roads — that have created this access problem.”

Alta Planning+Design’s study on the economic and health benefits of the WRG found that of the 100,000 residents living within a 10-minute walk of the proposed greenway, 2,500 were without access to a car, and 5,000 were below the poverty line.

The WRC is hoping to positively impact the health of the city by giving people better access to walking and biking trails.

In Memphis, 35 percent of the population is obese, and the diabetes rate is 50 percent higher than the national average. According to the Alta Planning+Design survey, the Memphis region will gain 1.19 million miles of walk trips and 1.25 million miles of bike trips once the greenway is complete. The survey found that the overall economic impact of the greenway will equal $14 million in combined health, transportation, environmental, and economic benefits.

But it isn’t just about connecting Memphians to walking trails and alternative transit. The greenway is also being designed to bring residents, who may not even know how to access the Wolf today, closer to the river. Better boat access to the Wolf is part of the master trail plan.

“We already have a very active recreational outreach program with 50-plus volunteer river guys who take people up and down the Wolf every year,” Cole said. “We could envision similar activities along the greenway, engaging neighborhoods and schools.”

At the end of the day, the WRC, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, is a land trust charged with conserving and enhancing the Wolf River by protecting the lands that surround it from future development. Cole and Wenner believe that building the WRG is the ultimate way to conserve and protect the river for years to come.

“We have this river, this asset, floating through our city,” Wenner said. “This is what we do to make it better. This is how we connect people to the river.”

Upcoming Open House Public Meetings on the Wolf River Greenway; all run from 5-8 p.m.: Oct. 20th – The Office @ Uptown (594 N. Second); Oct. 21st – Hollywood Community Center (1560 N. Hollywood); Oct. 22nd – Ed Rice Community Center (2907 N. Watkins); Oct. 27th – Raleigh Community Center (3678 Powers); Oct. 28th – Bert Ferguson Community Center (8505 Trinity)

BBBSMS

BBBSMS  Google Maps

Google Maps  ioby

ioby  Wolf River Conservancy

Wolf River Conservancy  Wolf River Conservancy

Wolf River Conservancy