The corner of South Main and G.E. Patterson has to be one of the most filmed locations in the country outside of New York and Los Angeles. For the past 20 years or so, many films have been shot in Memphis, and it seems like they all end up at this intersection, especially within the doors of the Arcade restaurant. From Elvis ghost stories in Mystery Train to a pre-tragedy family milkshake break in 21 Grams to a bizarrely boisterous celebration of its perfectly respectable chili in Elizabethtown, the Arcade has become a movie star.

It can seem a little silly sometimes that in a city full of promising locations, this one intersection is so ubiquitous. That the great Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai chose to set a third of his American debut, My Blueberry Nights, in Memphis with action taking place entirely in and around the Arcade and kitty-corner bar Earnestine & Hazel’s seems overly predictable.

Instead, My Blueberry Nights becomes something like the location’s apotheosis. The intersection is ready for its close-up, and Wong shoots it lovingly, from a fish-eye entrance by the Arcade facade to a moody shot of clouds reflected in the restaurant’s glass windows to the mysterious dark red glow inside Earnestine & Hazel’s to the wet grit of the street peeking over the bar’s neon sign.

My Blueberry Nights is the first American and English-language film from the adored cult filmmaker Wong, whose Hong Kong masterpieces such as Chungking Express, Fallen Angels, Happy Together, and In the Mood for Love are among the most celebrated international films of the past couple of decades.

The film — which opened the 2007 Cannes Film Festival to a very mixed reaction — stars pop singer Norah Jones in her acting debut and takes place over the course of one year in three distinctly American locations: Manhattan, Memphis, and the casinos and deserts of Nevada.

At the opening, a young woman named Elizabeth (Jones) walks into a Manhattan diner frequented by her boyfriend, who she suspects is seeing another woman. A brief conversation with the proprietor, Jeremy (Jude Law), confirms her suspicion. She leaves the boyfriend’s apartment keys at the diner to be picked up and leaves.

But the lovelorn Elizabeth keeps coming back to check on the keys, sharing pastries and stories with the similarly heartbroken Jeremy. Just when the relationship with Jeremy starts to intensify, Elizabeth bails, hopping on a bus for destinations unknown.

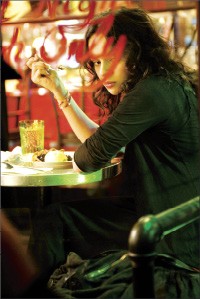

She ends up in Memphis, waiting tables at the Arcade by day under the name Betty and tending bar at Earnestine & Hazel’s by night as Lizzie. The Memphis segment is the strongest of the film, as Betty/Lizzie becomes something of an observer to a Tennessee Williams scenario involving alcoholic cop Arnie (David Strathairn) and his blowsy estranged wife, Sue Lynne (Rachel Weisz).

The third segment lands “Beth” in a backwater Nevada casino, where she befriends vivacious cardsharp Leslie (Natalie Portman) and gets involved in both a gambling scheme and Leslie’s family troubles.

Norah Jones as the heartbroken, pie-loving Elizabeth in My Blueberry Nights

This road-movie of sorts (written by Wong with American genre novelist Lawrence Block) is essentially an outsider’s vision of America as a neon-lit land of casinos, diners, and dive bars, where everyone drives a cool convertible and “Try a Little Tenderness” is always on the juke box. The boozy, tragic drama Elizabeth bears witness to in Memphis is as much a slice of Americana as the blueberry pie she ravages nightly in Manhattan. The film’s rapturous, unambiguous happy ending also feels like a cultural nod.

Unfortunately, the same rootless, wandering melancholy that’s so captivating in Wong’s Hong Kong films feels more contrived here, possibly because, to American audiences, the people and places are more familiar and the imagery less evocative. Where Wong finds mystery and romance in this classically American milieu, American audiences are more likely to find it in his Hong Kong settings.

Wong’s movies are much more about mood and image and moment than about story, and My Blueberry Nights is no different. Though the film has a conventional structure, the actual plotting is minimal. Wong is a repetitive, obsessive, fetishistic filmmaker. I don’t quite remember what his previous film, 2046, was about, but I’ll always remember Zhang Ziyi in that dress. Similarly, the memory of pop star Faye Wong surreptiously cleaning a crush’s apartment in Chungking Express with “California Dreamin'” blaring will forever be rattling around inside my head.

Wong is without his usual cinematographer, Christopher Doyle, but with Darius Khondji taking over, he still creates some imagery and moments that at least approach his best work. The film’s grainy texture is often lit with a red-orange glow characteristic of Chungking Express or Fallen Angels, though less extreme. And the opening-credit close-ups of vanilla ice cream melting and oozing through the seams of blueberry pie filling are an erotic bit of defamiliarizing.

My Blueberry Nights is, oddly, far more talky than Wong’s Hong Kong films, and as a result it suffers from erratic acting. Jones is an engaging and relatable presence but not really an actress — a fact made apparent when Weisz and then Portman enter and swallow the frame. Law tries too hard to ingratiate, his work exposed by the expert, laconic work of Strathairn, who gets, and nails, the film’s juiciest bit of dialogue, when he explains to bartender Lizzie the meaning of all the AA chips in his pockets — a handful of white ones symbolizing one day of sobriety and a lone purple chip recognizing 90 days clean. “I’m the king of the white chip,” he says, before ordering a whiskey to celebrate his “last day of drinking.”

What Jones lacks in chops she makes up for as an object of affection for Wong’s camera. But the cast here on the whole doesn’t provoke as much interest as Wong regulars such as Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung.

My Blueberry Nights is a trifle compared to something like In the Mood for Love, Wong’s 2000 masterwork, but it’s a lovely, romantic, visually stirring trifle. This minor-key mood piece may remind American filmgoers experiencing Wong for the first time of a sweeter version of Jim Jarmusch or a back-to-the-states sequel to Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation, a film that borrowed much from Wong. If nothing else, it ends with a bang in the form of the best on-screen kiss since Rear Window.

My Blueberry Nights

Now playing

Studio on the Square